School for Cultural and Social Transformation

4 The More You Know: Knowledge About Gender as Basis to Inclusive Healthcare Practices

Natalia Garrido (University of Utah)

Faculty Mentor: Claudia Geist (Division of Gender Studies, University of Utah)

Introduction

Research has documented the many barriers to accessing healthcare and receiving quality, affirming care for gender and sexual minority individuals (Arthur et al., 2021; Blakey & Aveyard, 2017; Casey et al., 2019; Magnan et al., 2005; Weingartner et al., 2022). Discriminatory implicit or explicit actions or biases, whether they are institutional or interpersonal, are some of the barriers that work to oppress sexual and gender diverse (SGD) minorities from getting the health care they need (Everelles, 2011b; Farmer et al., 2006; Hana et al., 2021; Bauer et al.; Winter, 2016). Just by experiencing discrimination alone, there have been positive connections to poor quality of life and mental health (Jackson et al., 2016; Mays & Cochran, 2001).

To shed light on possible solutions to providing more inclusive healthcare environments, we focus on attitudes and practices among future healthcare professionals, the essential first impressions for SGD patients. In recent studies, pre-health students express mostly positive attitudes toward SGD individuals (Blakey & Aveyard, 2017; Bell & Bray, 2014; Kong et al., 2009; Magnan & Norris, 2008; Magnan et al., 2005; Arthur et al., 2021), but studies show throughout the health fields there seem to be a range of poor to no training or education measures on SGD health within school curriculums and occupations (Pratt-Chapman & Phillips, 2020; Obedin-Maliver et al., 2011; White et al., 2015; Eliason, 2017; Lena et al., 2002). Failure to understand and empathize with these complex differences and interconnections of SGD identities and health have left the SGD community drowning in life-threatening and chronic health conditions (Jackson et al, 2016; Operario et al., 2015; Rosario et al., 2014).

Method

This study focuses on attitudes, views, and knowledge toward sexuality and gender via an online survey. The sample size contains 265 pre-health undergraduate students who have completed a specific amount of patient-centered hours and were enrolled in prerequisites courses for health programs.

Results

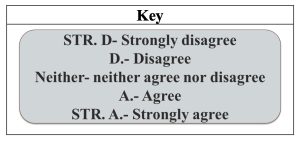

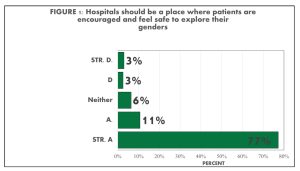

We found mostly positive and supportive attitudes toward SGD individuals. 88% of students noted that hospitals should be a place to safely express and explore gender identities (FIGURE 1). The vast majority of participants also indicated that in their patient care experience, they attempted to use the correct pronoun all of the time and preferred name regardless of medical records. As well, 87% of students considered themselves an LGBTQ ally for their patients (FIGURE 2). However, not all pre-health students were comfortable talking to a non-binary patient and still tended to guess the patient’s gender based on appearance.

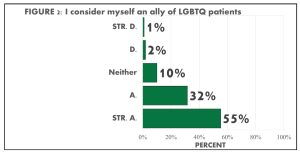

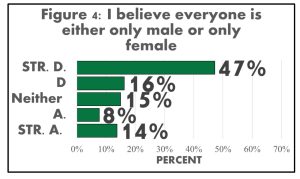

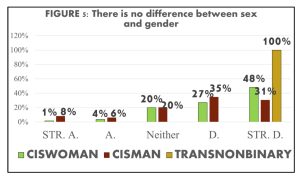

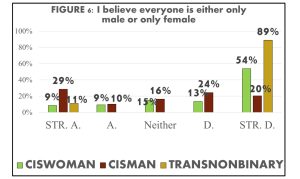

With abstract topics of gender and sexuality, most acknowledged the differences and binaries of gender and sex, but there was a constant undecided response (neither agree nor disagree) throughout the majority of the abstract questions. We found that 74% altogether disagreed with no difference between sex and gender and 7% altogether agreed while 19% neither agreed nor disagreed (FIGURE 3). For the question on sex being binary, 22% altogether agreed, 63% altogether disagreed and 15% neither agreed nor disagreed. The constant undecided response has further inquiries as to whether it is simply out of not wanting to choose, not knowing how to answer, or not understanding the question. Across the data of abstract topic questions, the more gender and sexual diverse a student identified, the more likely they noted they understood the complexities of sex and gender (FIGURE 5 & 6). Alongside understanding the complexities of sex and gender, it was found that mostly minority identities asked for pronouns.

It was also discovered that knowledge of SGD identities and their connection to inclusive behaviors contained a strong correlation. Though, we found stronger connections between inclusive behaviors with believing that sex is not binary and people being able to express more than one gender, compared to the knowledge that sex and gender are different.

Conclusion

These views and attitudes toward SGD patients can help the healthcare community find ways where we can destigmatize stereotypes and find the gaps in SGD health knowledge and training to create holistic healthcare. This data also further emphasizes that the attitudes of future healthcare providers are not the only foundations of exclusions in the healthcare system, but rather also a healthcare system and biased curriculum issue.

A reformation of the healthcare system should be the best option in making true holistic care. Steps must include examining social views from healthcare providers, understanding the regulations in health care education that intentionally or unintentionally avoid inclusivity, pushing a new comprehensive educational narrative of health care, and sharing data about gender and sexuality with local health institutions and practices. But it is also still the responsibility of future healthcare providers to make room and push inclusive policies and practices. Future healthcare professionals will continuously be the first impressions of SGD patients and whether they should trust the healthcare providers and health institutions. Inclusive actions and welcoming environments of representation will make a difference for SGD individuals to feel safer in healthcare areas.

In addition, this research, like many others, also further stresses the need to make room for SGD leadership in the reformation of the healthcare system. It is important to recognize that inclusion and diversity do not just mean only including sexual and gender minority individuals, but rather putting them in positions of leadership too. Giving SGD employees autonomy to work and change policies that promote inclusion and diversity removes any chances of changing policies and practices in a cis-gendered heteronormative way (Erevelles, 2011a). We must ask the leaders of SGD movements and SGD people in the community what they feel would make a better healthcare environment for them. Reformation must start within our local communities and it is everyone in the healthcare community’s responsibility to push forward for an affirming, quality, and accessible healthcare for all.

Bibliography

Arthur, S., Jamieson, A., Cross, H., Nambiar, K., & Llewellyn, C. D. (2021). Medical students’ awareness of health issues, attitudes, and confidence about caring for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender patients: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Medical Education, 21(56). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02409-6.

Bauer, G. R., Hammond, R., Travers, R., Kaay, M., Hohenadel, K. M., & Boyce, M. (2009). “I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives”: how erasure impacts health care for transgender people. Journal of the Association of Nurses in Aids Care, 20(5), 348- 361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.004.

Bell, A., & Bray, L. (2014). The knowledge and attitudes of student nurses towards patients with sexually transmitted infections: exploring changes to the curriculum. Nurse education in practice, 14(5), 512-517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2014.05.002.

Blakey, E. P., & Aveyard, H. (2017). Student nurses’ competence in sexual health care: A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23-24), 3906-3916. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13810.

Casey, L. S., Reisner, S. L., Findling, M. G., Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., Sayde, J. M., & Miller, C. (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Services Research, 54(S2), 1454- 1466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13229.

Eliason, M. J. (2018). LGBTQ cultures: what health care professionals need to know about sexual and gender diversity (3rd edition.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer.

Erevelles, N. (2011a). “Coming Out Crip” in Inclusive Education. Teachers College Record, 113(10), 2155-2185.

Erevelles, N. (2011b). Disability and Difference in Global Contexts: Enabling a Transformative Body Politic. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137001184.

Farmer, P. E., Nizeye, B., Stulac, S., & Keshavjee, S. (2006). Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine. PLOS Medicine, 3(10), e449. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030449.

Hana, T., Butler, K., Young, L. T., Zamora, G., & Lam, J. S. H. (2021). Transgender health in medical education. Bull World Health Organ, 99(4), 296-303. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.19.249086.

Jackson, C. L., Agénor, M., Johnson, D. A., Austin, S. B., & Kawachi, I. (2016). Sexual orientation identity disparities in health behaviors, outcomes, and services use among men and women in the United States: a cross-sectional study. BMC PUBLIC HEALTH, 16(807). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3467-1.

Kong, S. K. F., Wu, L. H., & Loke, A. Y. (2009). Nursing students’ knowledge, attitude, and readiness to work for clients with sexual health concerns. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(16), 2372-2382. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02756.x.

Lena, S. M., Wiebe, T., Ingram, S., & Jabbour, M. (2002). Pediatricians’ Knowledge, Perceptions, and Attitudes towards Providing Health Care for Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adolescents. Annals (Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada), 35(7), 406- 410.

Magnan, M. A., & Norris, D. M. (2008). Nursing students’ perceptions of barriers to addressing patient sexuality concerns. Journal of Nursing Education, 47(6), 260-268. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20080601-06.

Magnan, M. A., Reynolds, K. E., & Galvin, E. A. (2005). Barriers to addressing patient sexuality in nursing practice. MedSurg Nursing, 14(5), 282–290.

Mays, V. M., & Cochran, S. D. (2001). Mental Health Correlates of Perceived Discrimination Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91(11), 1869-1876. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869.

Obedin-Maliver, J., Goldsmith, E. S., Stewart, L., White, W., Tran, E., Brenman, S., Wells, M., Fetterman, D. M., Garcia, G., & Lunn, M. R. (2011). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender–Related Content in Undergraduate Medical Education. JAMA, 306(9), 971-977. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1255.

Operario, D., Gamarel, K. E., Grin, B. M., Lee, J. H., Kahler, C. W., Marshall, B. D. L., Van den Berg, J. J., & Zaller, N. D. (2015). Sexual Minority Health Disparities in Adult Men and Women in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2010. American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), e27-e34.https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2015.302762.

Pratt-Chapman, M. L., & Phillips, S. (2020). Health professional student preparedness to care for sexual and gender minorities: efficacy of an elective interprofessional educational intervention. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(3), 418-421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1665502.

Rosario, M., Corliss, H., L., Everett, B. G., Reisner, S. L., Austin, S. B., Buchting, F. O., & Birkett, M. (2014). Sexual orientation disparities in cancer-related risk behaviors of tobacco, alcohol, sexual behaviors, and diet and physical activity: pooled Youth Risk Behavior Surveys. American journal of public health, 104(2), 245-254.https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301506.

Weingartner, L., Noonan, E. J., Bohnert, C., Potter, J., Shaw, A. M., & Holthouser, A. (May 20, 2022). Gender-Affirming Care With Transgender and Genderqueer Patients: A Standardized Patient Case. MedEdPORTAL, 18(11249). https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11249

White, W., Brenman, S., Paradis, E., Goldsmith, E. S., Lunn, M. R., Obedin-Maliver, J., & Garcia, G. (2015). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: Medical students’ preparedness and comfort. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 27(3), 254-263. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2015.1044656.

Winter, S., Diamond, M., Green, J., Karasic, D., Reed, T., Whittle, S., & Wylie, K. (2016). Transgender people: health at the margins of society. The Lancet, 388(10042), 390-400. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00683-8.