College of Social & Behavioral Science

73 Impact of Trauma Exposure and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms on Baseline Self-Reported Safety Behaviors Versus Observer-Rated Safety Behaviors During the Trauma Film Paradigm

Caleb Woolston (University of Utah); Anu Asnaani (Psychology, University of Utah); Manny Gutierrez Chavez (University of Utah); and Kiran Kaur (University of Utah)

Faculty Mentor: Anu Asnaani (Psychology, University of Utah)

Abstract

Background: Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a high burden disorder marked by safety behaviors (SB), which are covert or overt actions used to escape distressing feelings or places. However, literature suggests scores on observer-rated and self-reported SBs can be discrepant, creating a need to examine if this discrepancy exists in those who have had a traumatic exposure or in those with both trauma exposure and significant PTSD symptoms, to examine how SBs may present in PTSD and trauma. We expect that the presence of significant PTSD symptoms will be correlated with greater SBs and will result in a greater discrepancy between these two types of SB reporting standards. Methods: We used an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine difference scores between an observer-rated measure of SBs performed by participants exposed to trauma-related videos and a self-reported measure of SBs at baseline. This was done across three groups: individuals with no trauma exposure (n= 77), those with trauma exposure but minimal symptoms (n= 49) and those with trauma exposure and likely PTSD (n=24). Results: PTSD symptoms were correlated with self-reported SBs (r = .44, p<.001), but not observer-rated SBs (r = -.15, p=.30). The ANOVA revealed a significant difference between self-reported and observer-rated SBs for those with probable PTSD compared to the other groups, who did not show this discrepancy between types of SBs (F(2,101) =3.53, p= .03), such that those with likely PTSD had greater self-reported SBs than observer-rated SBs. Conclusions: We found that individuals with probable PTSD showed significant discrepancy in types of SBs, which suggests SBs may be more covert for individuals with PTSD and harder for observers to spot in clinical or research settings, highlighting that SBs may differ in those with PTSD and emphasizing the need to provide education on how individuals with PTSD may mask their avoidance.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder, safety behaviors, trauma, trauma avoidance, exposure therapy

Impact of trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms on baseline self-reported safety behaviors versus observer-rated safety behaviors during the trauma film paradigm

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a multi-layered and complex disorder. It is a pervasive and potentially debilitating mental illness defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) as the presence of each the following points: A) a direct or indirect exposure to a traumatic event, B) presence of intrusion symptoms associated with the traumatic event beginning after the traumatic event occurred, including disassociation episodes or reoccurring distressing memories and/or nightmares, C) avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event, D) negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event, beginning or worsening after the traumatic event, E) marked alterations in arousal and reactivity associated with the traumatic event, including hypervigilance, and F) symptoms lasting over one month and not being due to effects of substances or medications (APA, 2013). One major factor that complicates the diagnostic process is that despite around 70% of the adult population experiencing a traumatic event at some point in their lives, such as military combat, sexual assault, or serious life- threatening illness or injury (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017), research has further shown that only around 8-15% of the general population will end up meeting diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Bryant-Genevier et al., 2021). This peculiar aspect of PTSD invokes a question as to what possibly differentiates patients who develop a PTSD diagnosis from those who do not following an exposure to trauma, a question that warrants scientific and empirical investigation.

Several current theoretical models of PTSD that exist to explain how PTSD occurs delineate the role that avoidance behaviors (i.e., the tendency to avoid thoughts, feelings or situations that remind one about the trauma) may play in maintaining symptom longevity of PTSD (LoSavio et al., 2017; Brewin & Holmes, 2003). Exposure-based treatments for PTSD target such behaviors, and involve guided, systematic, and repeated confrontation with feared stimuli, with significant evidence of their efficacy for PTSD (Brown et al., 2019). One particular target in exposure therapy is eliminating a type of avoidance known as safety behaviors (SBs, i.e., overt or covert actions performed to prevent, escape, or minimize a feared catastrophe and/or associated distress; VandenBos, 2015). Essentially, individuals utilize SBs to cope with the anxiety and distress of unpleasant feelings or the risk of feared outcomes associated with traumatic feelings, places, or events (Helbig-Lang & Petermann, 2010).

Those who use SBs intend to use them as a short-term means to relieve anxious feelings and symptoms (Helbig-Lang & Petermann, 2010). However, emerging research has shown that utilization of SBs has been shown to maintain those symptoms, rather than the intended purpose of reducing anxiety and fear (Allen et al., 2020). This leads to persistence of such symptoms, showing that the short-term relief provided by SB usage does not necessarily translate to long- term relief of mental health symptoms (Blakey & Abramowitz, 2016; Forsyth et al., 2016). Since SBs are a hallmark of trauma disorders (Blakey et al., 2021), the study of SBs is highly relevant to understanding the multi-layered relationship between PTSD and trauma exposure. The frequency of patient usage of SB has been shown to be a significant predictor of a PTSD diagnosis as well a correlate of severity of symptoms (Karamustafalioglu et al., 2006; Freeman et al., 2013; Goodson & Haeffel, 2018). Additional research has shown an association between SB engagement and traumatic intrusions in particular (McClure et al., 2019).

Despite these empirical findings, patients with PTSD and/or trauma exposure who utilize SBs are often hesitant to eliminate them. One likely explanation for this is that patients may misattribute positive outcomes in anxiety- and trauma-provoking situations to the use of SBs. For example, an individual who becomes anxious in a public place may exhibit the SBs of bringing anti-anxiety medication in anticipation of feeling anxious in public. If the anxious feelings do not arise, the patient may misattribute this to bringing the medications as opposed to other factors. In essence, the patient is assigning causality to the utilization of the SBs as the reason for maintaining safety rather than an actual cause of the traumatic or anxiety-inducing event not occurring. Furthermore, patients utilizing SBs seldom understand their actual role in maintaining symptoms rather than alleviating symptoms (Helbig-Lang & Petermann, 2010).

Safety behavior measuring methods can be divided into two distinct categories: subjective, or patient self-report methods, and objective observer-rated methods. Self-report methods are usually offered by clinicians and researchers as a questionnaire wherein the participant voluntarily self-reports frequency of SBs, usually during day-to-day activities. Objectively reported methods are those that are coded by an observer – for example, based on SBs performed during a task or video clip designed to elicit an anxious or trauma-like response (Olatunji & Fan, 2015). A more recently developed method of objectively measuring safety and avoidance behaviors is rating behaviors made by participants in a computer simulation game involving avoidance-like decision making in simulated events or situations (Myers et al., 2016). While methods vary, the goal of observation methods is to measure frequency of SBs’ usage and these objective measures are most often used to measure correlations with mental health symptoms.

Despite numerous empirically supported methods of measuring SBs, the process of examining the role trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms have on SBs is significantly complicated by research showing that there exists a significant discrepancy between subjective participant reporting of SBs and observer ratings of such behaviors in fear-based disorders more broadly. Specifically, Rowa et al. (2015) found that self-reported SB scores were greater than observed SBs when rated by a coder during a recorded speech test. Research done by Blakey et al. (2020) in the United States has shown that this discrepancy on reporting SBs can vary by region with cultural attitudes significantly influencing how some self-report SBs present. To our knowledge, however, there has been limited work that experimentally examines whether and how this discrepancy exists specifically in the context of PTSD when compared to those with a no traumatic exposure and/or a traumatic exposure that does not manifest as PTSD.

While SBs were only initially examined in the context of the broader class of anxiety disorders (i.e., generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder), there is growing interest in examining the role they may play in maintaining PTSD symptoms and diagnosis. However, there exists a dearth of research examining if this discrepancy also exists in participants with simply a history of an exposure to trauma or what role, if any, PTSD symptoms may play in explaining this reporting discrepancy. A major focus of exposure therapy is targeting and eliminating symptom-maintaining SBs, necessitating further examination into whether trauma exposure and/or PTSD symptoms may be associated with discrepancies between patient- reported as opposed to clinician-rated methods of safety behavior utilization.

Given this gap in the literature, the present study sought to examine if a discrepancy between self-reported and/or objectively measured, observer-rated SBs exists, and if this may be linked to an exposure to trauma, or the presence of significant PTSD symptoms. There were three aims of this present study: the first aim was to measure if the presence of PTSD symptoms were correlated with self-reported and/or observer-rated SBs. We hypothesized that there would be a significant correlation between the variables of both observer-rated and self-reported safety behavior in individuals reporting greater PTSD symptoms. The second aim of this study was then to examine if there were any significant differences in the self-reported and observer-rated SBs across three groups: those with no trauma exposure, those with a past trauma exposure but few PTSD symptoms, and those with trauma exposure and significant PTSD symptoms. Based on previous literature examining the role SBs play in symptom severity and maintenance, we expected that the groups with trauma exposure and minimal PTSD symptoms and probable PTSD would have a significantly greater number of both kinds of SBs compared to those with no trauma exposure. The third and final aim herein was to test if a discrepancy between the two types of safety behavior reporting methods would be associated with specific group membership. We lastly hypothesized that a difference in reporting discrepancy between types of SBs would be statistically associated with having probable PTSD only, in line with research in other fear-based disorders (Blakey et al., 2020).

Methods

Participants

Institutional Review Board approval was given for all research and procedures performed in this study. Signed informed consent was received from all participants and all data were deidentified. Participants (N=150) for this experiment were recruited as part of a larger study conducted by a research laboratory at a public university in the Mountain West region of the United States. Recruitment for this study was done via SONA, a centralized online recruitment program for recruitment of undergraduate students, for which participation in this study was awarded course credit. The sample included participants identifying ethnically as 62.0% white,19.7% Hispanic or Latino, 8.3% Asian/Pacific Islander, 1% Native American, 2.2% Black, and 7.3% other races. Demographics additionally included 24.2% first-generation college students and 34.6% upper income-class participants.

Materials

Trauma Film Paradigm. This task consisted of one of two different video clips viewed by study participants. The videos were both five-and-a-half minute long videos of potentially fatal car crashes. Specifically, one of the videos was a compilation of various scenes of car crashes with injuries explicitly shown and the other was of unedited footage of one particular car crash shown in a full five-and-a-half-minute long interval. These clips have been shown to elicit anxious feelings and were designed to evoke SBs in participants who utilize them (Olatunji & Fan, 2015). Due to a desire to maintain social distancing in light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, these videos were displayed on the participant’s own computer while on a live video Zoom call with a lab assistant.

Self-Reported Safety Behavior Assessment Form (SBAF). The Safety Behavior Assessment Form (SBAF) was utilized in this study to measure subjective self-reported safety behavior utilization. The SBAF is a self-report questionnaire wherein participants respond to a 41-item battery regarding various SBs they may potentially utilize in day-to-day activities, including questions/statements such as, “Do you over-plan for everyday events?” and “I stay on the outside of crowds and/or monitor for exits or escape routes”. Participants rate each question on a scale of zero, one, two, or three, with each number corresponding to “never”, “sometimes”, “often”, or “always”, respectively (Goodson et al., 2016). Each question is further categorized into one of four subscales, in addition to a total overall score. These subscales are vigilance (7 items), social (7 items), health (8 items), or PTSD (12 items) and seven unaffiliated questions contributing to the final score, and the range of total scores was 0 to 123. Previous research has shown that this measure has high levels of internal consistency and test-retest reliability (r = .76), as well as an excellent level of internal consistency (α = .92) and may be used by clinicians and experimenters to measure patient SBs for treatment/research (Goodson et al., 2016). Internal consistency of the SBAF total measure in the current sample was excellent (α=90).

Objectively-Rated Safety Behavior Coding. The observer-rated SB measure was scored via a behavioral coding measure specifically designed for this study. Specifically, videos of study participants engaging in the trauma film paradigm were recorded and later coded by undergraduate research assistants trained to code for observed SBs by a licensed clinician. Research assistants were specifically trained to record the frequency and type of various observed participant SBs, including items such as how often the participant looked away from the screen or how often they engaged with the lab assistant to feel safer. Training procedures included having coders rate three test subjects with 90% accuracy to the scores obtained by the training clinician, and only being cleared to conduct study coding upon reaching this threshold with three consecutive test participants. There were ten questions rated by the coders on a scale of zero, meaning “not at all”, to four, meaning “very often”, on how often these behaviors were exhibited over the viewing of each distressing film. These included the observer rating behaviors such as delaying starting the films and intentionally engaging the observer to avoid the film. Additionally, some questions included a scale measuring intensity of the behaviors, also measured on a zero, meaning “never” to four, meaning “very intense behavior”. The total score had a range of scores of zero to forty. Data regarding observed SBs were recorded in the survey software program Qualtrics to generate a total score of observable SBs during each distressing film task.

PC-PTSD-5. The PC-PTSD-5 is a five-question clinical assessment self-report questionnaire that assesses for probable PTSD. The questionnaire asks participants questions on a yes or no scale, initially asking if the participant has experienced any one event of a list of traumatic events such as combat, having been in an accident, having a close loved one die through homicide or suicide, among others. If the participant answers “yes”, they are then asked five follow-up questions that ask details about the presence of PTSD symptoms in the past month (yes or no). This portion of the questionnaire includes questions such as “had nightmares about the event(s) or thought about the event(s) when you did not want to?” and “have you been constantly on guard, watchful, or easily startled?”, to which participants answer “yes” or “no”. Scores can range from 0 to 5, with those scoring three or higher categorized as having “probable PTSD”. Previous research with the PC-PTSD-5 has shown good test-retest reliability (r = 0.83) as well as strong internal validity (r=.083; Prins et al., 2016). Internal consistency of this measure in the current sample was found to be good (α=.79).

Procedure

After informed consent was received from participants, individuals were asked to fill out the SBAF and PC-PTSD-5. Participants were then given one of the two distressing films from the trauma film paradigm to view, which they were asked to complete either before or after a separate breath holding task (not examined in this study), in addition to subsequently completing one of three interventions (interoceptive exposure, mindfulness, and a positive self-efficacy induction) occurring after the trauma film paradigm that were aimed at improving participants’ distress tolerance (which were also not the focus of the current paper). They then were given the second trauma video to view either before or after another breath-holding task (with counterbalanced order; this second video was also not examined in the current study). During these tasks, participants’ behaviors were monitored and recorded via the Zoom meeting. After completion of the entire study, all participants were debriefed and provided with support resources if they requested, as this study included exposure to distressing videos and risked being emotionally upsetting to participants. The recorded videos of participants viewing the trauma film videos before and after intervention were then later coded for SBs by the aforementioned coders. As mentioned above, for the current study, only SBs observer-coded for the trauma film viewed before the provided intervention were examined and compared to participant self- reported SBs at baseline.

Data Analysis

All data were analyzed via the statistical software program SPSS Statistics version 27. Initially, we ran the suggested scoring guidelines to organize participant data into three groups of either non-trauma exposed, trauma-exposed with minimal PTSD, and trauma exposed with probable PTSD, based on scores on the PC-PTSD-5 to address aims 2 and 3. Specifically, participants who answered “no” to the first question, i.e., if they had a previous exposure to a traumatic event, were placed in the non-trauma exposed group (n = 77). Those endorsing a trauma exposure but answering ‘yes’ to only one or two of the remaining questions were placed into the trauma-exposed group (n = 49). Participants reporting a trauma exposure and endorsing three or more PTSD symptoms on the PC-PTSD-5 were placed into the probable PTSD group (n= 24), based on previously suggested scoring guidelines for this measure (Williamson et al., 2022).

Data regarding subjective self-reported SBs as measured by the SBAF (including the vigilance, social, health, and PTSD subscales, and the total score) and the observer-coded safety behavior usage data were correlated with the score on the PC-PTSD-5 (Aim 1). Following this, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to test if there were significant differences in self-reported or observer-rated SBs across any of the three trauma exposure groups (Aim 2). Finally, to examine whether there was a significant difference between the discrepancies on both types of SBs and whether this was associated with any of the trauma groups (Aim 3), the self- report and observer-rated measures were compared by first z-scoring the SBAF total scores and the video-coded observer scores and calculating the difference between the two sets of z scores. This difference z score was then compared across the three groups of participants via a between- groups ANOVA, followed up with pairwise comparisons to examine any significant differences between groups in the discrepancy between self-reported and observer-rated SBs, at the significance level of p=.05.

Results

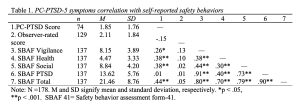

For Aim 1, correlations regarding SBs for both the self-report and observer-rated measures with the PC-PTSD-5 score can be found in Table 1. Briefly, observer-rated scores were not found to be statistically associated with PC-PTSD-5 scores (see Table 1). However, each of the subscores on the self-reported SBAF, other than the PTSD subscore and the total score were found to be positively correlated with greater scores on the PC-PTSD-5.

Table 1. PC-PTSD-5 symptoms correlation with self-reported safety behaviors

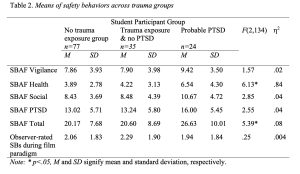

Table 2 presents mean scores of observer-rated and self-reported SBs across the three trauma groups for Aim 2. Briefly, the ANOVA revealed no significant differences among the three groups on observer-rated SBs, F(2,128)=.25, p=.78. Regarding SBAF scores, A significant difference across groups was found in the SBAF scores of health subscore (F(2,136)=6.13, p<.01) and total score (F(2,136)=5.39, p<.01) only, such that the probable PTSD group showed increased mean scores on the health subscale and the SBAF total score (see Table 2). The vigilance subscore, F(1,136)=.1.57, p=.21, the social subscore, F(2,136)=2.85, p=.06, and the PTSD subscore F(2,136)=2.56, p=.08, were all found to not be significant across the groups.

Table 2. Means of safety behaviors across trauma groups Student Participant Group

For Aim 3, to analyze the difference in the discrepancy between observer-rated and self- reported SBs, the between-groups ANOVA of the z-scored data revealed a significant difference in means between the two types of SB reporting in the probable PTSD group only (difference of means = .82), such that participants with probable PTSD had greater SB scores on the SBAF than their observer ratings of their SBs during exposure to the trauma film paradigm. Pairwise comparisons further confirmed that this discrepancy was statistically greater for the probable PTSD group when compared to the no trauma exposure group (F(1,65)=7.18, p<.01), and the trauma exposure with no PTSD group, (F(1,51)=5.23, p<.05). This difference in the discrepancy between self-reported versus observer-rated SBs was not found between the no trauma exposure group (difference of means= -.15) or the trauma exposed but minimal symptom group (difference of means=.20). The non-trauma exposed and the trauma exposed with minimal PTSD symptom group did not differ statistically from one another (difference of means = -.13, F(1,82)=.03, p=.87).

Discussion

An increased presence of PTSD symptoms was not correlated with higher observer-rated SBs; however, it was correlated with higher scores on all subscales except PTSD on the self- reported SBAF (i.e., self-reported SBs). This is partially consistent with literature explaining the role SBs play in symptom severity and maintenance. The hypothesis of associations of differences in the SB reporting methods across the groups was also partially supported, whereby significant differences were found across the groups for SBAF health subscale and the total scores, such that there were higher self-reported SBAF scores in these domains for those with probable PTSD only. The difference between SB reporting scores was not significant for observer-rated or the SBAF vigilance, social, or PTSD subscore SBs, and those with trauma exposure with minimal PTSD symptoms did not show significant elevations on any of the SB types compared to those with no trauma exposure. The final hypothesis was fully supported by the data, where a significant discrepancy was found between self-reported and observer-rated SBs, such that only those with probable PTSD higher scores obtained via the self-reported methods compared to observer-rated methods of SBs. This pattern was not found in either groups of those with no trauma exposure or those with trauma exposure but minimal PTSD symptoms by the pairwise comparisons.

Evolutionary theory may assist in explaining why patients with likely PTSD may utilize SBs that are more covert, rather than overt: specifically, background literature postulates that PTSD is one of the most stigmatized disorders in the DSM-5 (Krzemieniecki & Gabriel, 2019). This high level of stigmatization may give patients with PTSD greater reason to hide any behaviors (including SBs) that may clue others into whether the individual has PTSD. In short, patients with PTSD may have learned to adapt by utilizing covert SBs (rather than overt and thus more easily observable behaviors), possibly in an effort to preserve the guise of public functioning. Findings in this study further underscore the importance of examining how the elimination of all safety behaviors (overt and covert) may improve outcomes in exposure therapy for PTSD.

Further, the misattributed advantages of utilizing covert SBs a create a need for education regarding the unique presentation of SBs used by those with PTSD. These findings may show that people with PTSD are harder to identify in public or that the avoidance conferred by their symptoms may not be readily apparent to those in their social and community networks. Educating the public on the fact that just because an individual may not, on the surface, seem to have PTSD symptoms or engage in overt trauma avoidance, that such a lack of overt SBs does not necessarily translate into an individual not having any PTSD symptoms. This finding emphasizes the need for empathy from the public as well as general societal education on the need to be aware that those with PTSD may still benefit from therapies that help these individuals approach trauma-related stimuli. An additional implication of this research is that PTSD SBs may present in a unique manner. Our current methods of treating PTSD could likely benefit from these findings which highlight the unique ways PTSD presents itself. This finding underscores the need to further educate clinicians and researchers (beyond the general public) on the nature of PTSD SBs and how they present differently from those without PTSD. Increasing our understanding of SBs may also assist in more effective assessment, examination, and treatment of PTSD.

In addition to clinical implications, these findings are consistent with previous literature that postulates that a traumatic exposure is a very different phenomenon than PTSD in many significant ways (Zohar et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2019), as was clear from our findings that having trauma exposure alone (in the absence of significant PTSD symptoms) did not show higher SBs. That is, PTSD is differentiated from traumatic exposure (specifically without PTSD) by its persistence and debilitating symptomology as well as a disturbance in one’s functioning (Ehring et al., 2008, Miao et al., 2018). In addition, trauma exposure measures in research and clinical settings typically seek to measure the presence of an exposure to a traumatic event, and do not serve as a diagnostic tool whereas a PTSD measurement seeks to determine a matching symptom presentation as determined by the DSM-5, generally for diagnostic purposes (Hall & Hall, 2007). While SB usage may play a role in traumatic exposure evolving into PTSD, further research is needed to examine if having a difference in the types of SBs used plays a role in the relationship between exposure to trauma and subsequent PTSD diagnosis.

Strengths of the present study include good sample sizes considering population size of those with PTSD, good internal consistency of measures, use of well-supported measures, and overall good generalizability of the sample. Yet, while this study has such notable strengths, there are some limitations that ought to be addressed in future studies. Specifically, the current sample was limited to only college students and had an overrepresentation of higher income students, which somewhat limits the degree to which we can generalize these findings to middle or lower income as well as non-college educated populations, communities and age groups. Also, the nature of examining SBs outside of everyday life may skew how observer-rated SBs present. Specifically, it could be that we were measuring different contexts for SBs with the SBAF examining SBs performed in daily activities, while the observer-rated measure was specifically in the context of a stressful film task. Additionally, the trauma paradigm used in this study was a compilation of car accidents, and while most would find these videos upsetting, different videos could elicit different responses based on one’s unique trauma (e.g., those with a sexual assault traumatic exposure would not have the same traumatic reaction as those with a trauma from car accidents). However, due to background literature suggesting the trauma film paradigm does indeed elicit traumatic reactions (Olatunji & Fan, 2015), we believe the effect of incongruent traumatic reactions with the car accident films is very limited.

Future studies should examine the specific factors that may explain why some SBs, but not all, are utilized by those with PTSD and whether we can replicate the current findings that some scores do not have a significant difference in the reporting discrepancy while others do (e.g., why self-reported vigilance was not found here to be significantly correlated with PTSD and other types were). Additionally, further research examining what other variables intersect with SBs and that may differentiate those who do develop PTSD from traumatic exposure and those who do not is needed (Dunmore et al., 2001; Ehring et al., 2008). Future studies should also focus on replication, such as utilizing samples that include the general population rather than solely college students and better sample representation of ethnic minorities to more closely examine possible cultural or generational/age-related differences in the presentation of various types of SBs. Despite these limitations and the need for additional research, this study enhanced understanding of how SBs present in college students with probable PTSD and how they differ from those without PTSD. Clinicians can benefit from understanding the diverse nature of SBs and how to recognize the diverse ways they manifest in those with probable PTSD.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Treatment Mechanisms, Community Empowerment, and Technology Innovations (TCT) Lab at the University of Utah (PI: Asnaani) for the opportunity to conduct this research. I want to especially thank Ifrah Majeed, the research coordinator, for overseeing data collection, entry, and remote implementation of participant recruitment. I also want to thank my fellow undergraduate research assistants Ally Askew, Jiayu Gao, Angela Pham, Sami Soufi, Tracey Tacana, Will Tanguy, and Michael Wasser for assisting in coding and data collection. I want to additionally thank my graduate advisors Kiran Kaur, Jennifer Isenhour, and Manny Gutierrez Chavez for their help in the research and editing process. I am also very thankful to Dr. Anu Asnaani for the opportunity to examine this study idea, and for accommodating an Honor’s Thesis despite the many challenges with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, I am thankful to Dr. Lisa Aspinwall and Dr. Trafton Drew who serve as the department’s Honors Thesis Advisors and provided invaluable feedback on the final paper. Last but not least, I would like to thank all of the research participants for assisting in this research by participating in our somewhat challenging research procedures.

Bibliography

Allen, E., Renshaw, K., Fredman, S. J., Le, Y., Rhoades, G., Markman, H., & Litz, B. (2020). Associations between service members’ posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and partner accommodation over time. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(3), 596– 606.https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22645

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Trauma- and stressor-related disorder. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (pp. 271-280). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Blakey, S. M., & Abramowitz, J. S. (2016). The effects of safety behaviors during exposure therapy for anxiety: Critical analysis from an inhibitory learning perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 49, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.07.002

Blakey, S. M., Kirby, A. C., McClure, K. E., Elbogen, E. B., Beckham, J. C., Watkins, L. L., & Clapp, J. D. (2020). Posttraumatic safety behaviors: Characteristics and associations with symptom severity in two samples. Traumatology, 26(1), 74–83. https://doi- org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.1037/trm0000205

Brewin, C. R., & Holmes, E. A. (2003). Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(3), 339–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272- 7358(03)00033-3

Brown, L. A., Zandberg, L. J., & Foa, E. B. (2019). Mechanisms of change in prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Implications for clinical practice. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 29(1), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000109

Bryant-Genevier, J., Rao, C. Y., Lopes-Cardozo, B., Kone, A., Rose, C., Thomas, I., Orquiola, D., Lynfield, R., Shah, D., Freeman, L., Becker, S., Williams, A., Gould, D. W., Tiesman, H., Lloyd, G., Hill, L., Byrkit, R. (2021). Symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation among state, tribal, local, and territorial public health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, March–April 2021. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(26), 947–952. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7026e1

Correll, D. N., Engle, K. M., Lin, S. S., Lac, A., & Samuelson, K. W. (2021). The effects of military status and gender on public stigma toward posttraumatic stress disorder. Stigma and Health, 6(2), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000222

Craske, M. G., Treanor, M., Conway, C. C., Zbozinek, T., & Vervliet, B. (2014). Maximizing exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006

Dunmore, E., Clark, D. M., & Ehlers, A. (2001). A prospective investigation of the role of cognitive factors in persistent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after physical or sexual assault. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39(9), 1063–1084. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00088-7

Breslau, N. (2009). The Epidemiology of Trauma, PTSD, and Other Posttrauma Disorders.

Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(3), 198-210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838009334448

Ehring, T., Ehlers, A., & Glucksman, E. (2008). Do cognitive models help in predicting the severity of posttraumatic stress disorder, phobia, and depression after motor vehicle accidents? A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.76.2.219

Freeman, D., Thompson, C., Vorontsova, N., Dunn, G., Carter, L.-A., Garety, P., Kuipers, E., Slater, M., Antley, A., Glucksman, E., & Ehlers, A. (2013). Paranoia and post-traumatic stress disorder in the months after a physical assault: A longitudinal study examining shared and differential predictors. Psychological Medicine, 43(12), 2673–2684. https://doi.org/10.1017/s003329171300038x

Forsyth, J. P., Eifert, G. H., & Barrios, V. (2016). Fear conditioning in an emotion regulation context: A fresh perspective on the origins of anxiety disorders. Fear and Learning: From Basic Processes to Clinical Implications., 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1037/11474- 007

Goodson, J. T., Haeffel, G. J., Raush, D. A., & Hershenberg, R. (2016). The Safety Behavior Assessment Form: Development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(10), 1099–1111. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22325

Goodson, J. T., & Haeffel, G. J. (2018). Preventative and restorative safety behaviors: Effects on exposure treatment outcomes and risk for future anxious symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(10), 1657–1672. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22635

Hall, R. C., & Hall, R. C. (2007). Detection of malingered PTSD: An overview of clinical, psychometric, and Physiological Assessment: Where Do We Stand? Journal of Forensic Sciences, 52(3), 717–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2007.00434.x

Helbig-Lang, S., Petermann, F. (2010). Tolerate or eliminate? A systematic review on the effects of safety behavior across anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(3), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01213.x

Karamustafalioglu, O. K., Zohar, J., Güveli, M., Gal, G., Bakim, B., Fostick, L., Karamustafalioglu, N., & Sasson, Y. (2006). Natural course of posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(06), 882–889. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v67n0604

Krzemieniecki, A., & Gabriel, K. I. (2019). Stigmatization of posttraumatic stress disorder is altered by PTSD Knowledge and the precipitating trauma of the sufferer. Journal of Mental Health, 30(4), 447–453.https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2019.1677870

Lewis, S. J., Arseneault, L., Caspi, A., Fisher, H. L., Matthews, T., Moffitt, T. E., Odgers, C. L., Stahl, D., Teng, J. Y., & Danese, A. (2019). The epidemiology of trauma and post- traumatic stress disorder in a representative cohort of young people in England and Wales. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(3), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215- 0366(19)30031-8

LoSavio, S. T., Dillon, K. H., & Resick, P. A. (2017). Cognitive factors in the development, maintenance, and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Current Opinion in Psychology, 14, 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.09.006

McClure, K. E., Blakey, S. M., Kozina, R. M., Ripley, A. J., Kern, S. M., & Clapp, J. D. (2019). Behavioral inhibition and posttrauma symptomatology: Moderating effects of safety behaviors and biological sex. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(7), 1350–1363. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22778

Miao, X.-R., Chen, Q.-B., Wei, K., Tao, K.-M., & Lu, Z.-J. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder: From diagnosis to prevention. Military Medical Research, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-018-0179-0

Myers, C. E., Radell, M. L., Shind, C., Ebanks-Williams, Y., Beck, K. D., & Gilbertson, M. W. (2016). Beyond symptom self-report: Use of a computer “avatar” to assess post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Stress, 19(6), 593–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2016.1232385

National Institute of Mental Health (2017). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Retrieved December 3, 2022, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/post-traumatic-stress- disorderptsd.shtml.

Olatunji, B. O., & Fan, Q. (2015). Anxiety sensitivity and post-traumatic stress reactions: Evidence for intrusions and physiological arousal as mediating and moderating mechanisms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 34, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.06.002

Prins, A., Bovin, M. J., Smolenski, D. J., Marx, B. P., Kimerling, R., Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A., Kaloupek, D. G., Schnurr, P. P., Kaiser, A. P., Leyva, Y. E., & Tiet, Q. Q. (2016). The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(10), 1206–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5

Rauch, S. A., Yasinski, C. W., Post, L. M., Jovanovic, T., Norrholm, S., Sherrill, A. M., Michopoulos, V., Maples-Keller, J. L., Black, K., Zwiebach, L., Dunlop, B. W., Loucks, L., Lannert, B., Stojek, M., Watkins, L., Burton, M., Sprang, K., McSweeney, L., Ragsdale, K., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2021). An intensive outpatient program with prolonged exposure for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: Retention, predictors, and patterns of change. Psychological Services, 18(4), 606–618. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000422

Rowa, K., Paulitzki, J. R., Ierullo, M. D., Chiang, B., Antony, M. M., McCabe, R. E., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2015). A false sense of security: Safety behaviors erode objective speech performance in individuals with social anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy, 46(3), 304–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.11.004

Samuel, D. B., Suzuki, T., &; Griffin, S. A. (2016). Clinicians and clients disagree: Five implications for clinical science. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(7), 1001–1010. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000201

Williamson, M. L., Stickley, M. M., Armstrong, T. W., Jackson, K., & Console, K. (2022). Diagnostic accuracy of the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM‐5 (PC‐PTSD‐5) within a civilian primary care sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(11), 2299–2308. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23405

Zohar, J., Juven-Wetzler, A., Sonnino, R., Cwikel-Hamzany, S., Balaban, E., & Cohen, H. (2011). New insights into secondary prevention in post-traumatic stress disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(3), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2011.13.2/jzohar