College of Humanities

45 Implementing Education on Objectification Theory and Why it is More Beneficial for Women’s Issues than the Body Positivity Movement

Lauren Lloyd (University of Utah)

Faculty Mentor: Kimberley Mangun (Communications, University of Utah)

ABSTRACT

The Sexual Objectification Theory proposed by Barbara Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Roberts postulates that the sexual objectification of women can lead to depression, eating disorders, and sexual dysfunction. Further research on this theory has shown that objectification is widespread and has several consequences such as diminished mental health in women and increased rates of violence against women. This phenomenon and its effects have worsened with the advent of social media. On social media platforms, women are frequently exposed to sexually objectifying content and unattainable beauty standards. The body positivity movement combats the destructive messages in the media by empowering women through realistic representations of women’s bodies. While the body positivity movement has made great progress in the realm of objectification, the movement is divisive and limited in its capabilities. To reduce the rampant objectification in society, we must formally educate future generations on objectification and its ramifications. Therefore, I propose a lesson plan for the Utah Core Standards of three, 45-minute class periods. The curriculum contains two PowerPoint presentations, two videos, two images, one article, one activity, one handout, and one Socratic seminar.

Introduction

I was objectified for the first time when I was 12 years old. The boys in my grade decided to craft the “perfect girl’s body” using different physical features from the girls in our grade. Word got around about whose body parts they selected. When I found out which part of my body was chosen for this “perfect girl,” I was mortified. I look back on this experience and pity that poor 12-year-old girl, who had just realized for the first time in her short life that she had no control over her own body. Instead, her body was now controlled by the boys who viewed her as an object first, and a person second. This experience opened the floodgates for a torrent of sexually objectifying experiences that I would face during my adolescence.

After I hit puberty, my mother would become enraged when we walked in public together and she saw the way adult men ogled me. School administrators reprimanded me for wearing clothing permitted by the dress code because my chest developed earlier than the other girls in my grade. College-aged men catcalled at me anytime I walked by the local university. I was given the nickname “thick thighs” in high school. Unfortunately, my experience is not unique. Sexually objectifying experiences function as a disgusting and upsetting rite of passage for young girls into womanhood.

Sexually objectifying experiences occur when women are reduced to their bodies, or a collection of their body parts, for the gratification of other people.1 These experiences can occur within women’s daily interactions and also online when they come across sexually objectifying media. Sexually objectifying media emphasizes women’s bodies over anything else, as if their bodies alone are able to represent them as a whole.2 In the past decade, social media has become a predator, and its prey are young, vulnerable girls who have no defense against objectification, body shaming, and sexualization. On these platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, they are subjected to extremely limited representations of what women are supposed to look like. Advertisements follow suit on their timelines and convince girls that they are worth nothing unless they are free of acne, body hair, fat, cellulite, stretch marks, or any imperfection. Then, they are bombarded with videos and images of women in minimal clothing who are showcased for male approval. Just by existing in the world as a young woman, whether she is at school or work, scrolling on social media, or minding her own business in public, women witness an obscene amount of objectification.

As I got older, I began to notice the toll that objectification was having on myself and the women around me. It broke my heart to see my best friends scrutinize every aspect of their appearance and degrade themselves. I empathized with them when they broke down sobbing over a picture of themselves that they didn’t like. I noticed patterns of restricted eating with the women in my life, especially for those who had lived through the ’90s. It was normal to hear comments such as “good thing I worked out today” or “guess I won’t be eating tomorrow” anytime I sat down for a large meal with women. These women whom I loved and valued for their kindness, their intelligence, and their humanity hated themselves just because they didn’t look like the fictitious images of women who were praised in the media. These examples represent casual and normalized consequences of objectification. In this thesis, I will highlight the more dangerous side effects of objectification including eating disorders, depression, sexual dysfunction, and violence against women.

I spent all of my high school years envying my friends’ physiques, all the while they were wishing that they looked like somebody else. Women are constantly comparing themselves to other women. It doesn’t matter what a woman looks like; as long as objectification is ubiquitous in society, she will never be content with her appearance. However, my and many other women’s self-image improved tremendously once we were exposed to the body positivity movement. The movement stems from the fat rights movement which was founded in the 1970s. Once fat rights activists took to Tumblr and Instagram during the early 2000s, it was rebranded as the body positivity movement by the new generation.3 Activists within the movement highlight the authentic version of themselves and give women tools to build their confidence. Seeing a variety of body types positively represented in the media helps women accept themselves as they are.

I became enthralled with the body positivity movement, and I wanted to share it with other women who struggled with their body image. Therefore, I began this thesis in my sophomore year of college. It started out as an enterprise story for my journalism class about the body positivity movement. I interviewed three accomplished women who shared their insights and experiences of objectification with me. I wrote this piece, and it was published on UNewsWriting.org. Yet, when it was finished, I felt like the work had just begun. I had so much more to say and learn about the objectification of women. So, the following year, I began my research for this thesis. I pored over a plethora of academic papers and carefully parsed school curriculums. At times, it felt heavy. I was overwhelmed by the stories of all the women who were suffering. This is when I realized why this work is so important. If I wanted my mother, my grandmother, my friends, and all of the inspiring women I know to value themselves the way that I valued them, something needed to change.

The body positivity movement has several benefits for women, such as increasing representation of body types, improving women’s body image, and creating an empowering online community. These changes are not enough. Fortunately, there is an abundance of resources to help women unlearn the self-hatred that objectification has instilled in them. However, it is an arduous process to unlearn the values that have been taught to you since you were a child. Women have to suffer the effects of objectification, and then do the work to dismantle it as well. Furthermore, there are so many differing opinions and factions within the movement that its effectiveness has been diminished. Critics of the movement discuss how it perpetuates an emphasis on physical appearance, and it largely benefits white women. Some believe that body positivity should be for everyone. Others want to emphasize that body positivity is different for plus-sized women and women of color because our culture places the most value in white, thin bodies.4 When women are further pitted against other women, progress is derailed.

I propose that the solution to this issue is to educate boys about the harm of objectification. If men and women are equally informed on the effects of objectification, there is a higher chance of altering objectifying social norms. Women are perpetually surrounded by objectification, so they can easily comprehend when it is occurring and how it will detrimentally impact the victim. Men do not have the same perspective on objectification because they are not as frequently the subjects of it. Objectification can no longer be just a women’s issue. Women can work on their confidence and self-esteem for their entire lives, but the problem will not improve for the following generations if the issue is not attacked head-on.

To confront the problem of objectification directly, I designed a school curriculum for 7th- and 8th-grade health students in Utah. I posit that teaching youth about objectification will make objectifying attitudes less normalized in society, which will improve girls’ mental health and reduce rates of violence against women. In this curriculum, students will learn what objectification is, the negative impacts of it, and how they can be a part of the solution. I chose to include this lesson plan for 7th- and 8th-grade students because it naturally fits into the content of the Utah Core Standards and would be simple for teachers to implement. This is also a crucial time for teenagers’ development. I was objectified for the first time when I was 12, when I was in the 7th grade. Maybe if those boys had studied the harmful effects of objectification, then that 12-year-old girl would not have learned that her worth as an individual lies in her appearance.

Literature Review: Objectification Theory

The Sexual Objectification Theory was first proposed in 1997 by Barbara Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Roberts. Their theory posits that women are socialized to internalize objectification and treat themselves as objects.5 This is referred to as self-objectification, and it has a detrimental impact on women’s mental health.6 Fredrickson and Roberts determined two routes in which women arrive at these serious mental health problems. First, when women are sexually victimized through rape, incest, assault, or sexual harassment, there is a direct pathway to depression, eating disorders, and sexual dysfunction.7 Second, when women internalize the proliferation of objectification in society, there are physiological consequences that manifest into these larger mental health issues.8 For example, self-objectification results in appearance anxiety and body monitoring, which leads to depression and disordered eating.9 Self-objectification also leads to diminished internal awareness, body shame, and general anxiety, all of which may result in sexual dysfunction.10 The connection between self-objectification and diminished mental health is perpetuated by visual media, such as films, advertisements, television, music videos, and women’s magazines that contain sexualized images of women, and interpersonal encounters.11 This is why the pervasive nature of social media is so damaging for women. Fredrickson and Roberts assert that this sexualization of women in the mass media is so ubiquitous that most, if not all women in American society are impacted by it.12 This is the seminal study in this area of research, and scholars are still expanding on it to this day.

Mental Health Impacts

A 2019 study has explored how this frequent exposure to sexual objectification in daily life negatively impacts women’s everyday emotions. The researchers determined that objectifying events, such as catcalling or car honking, sexual remarks made about the body, nonconsensual touching or fondling, and sexually degrading actions still induce self- objectification in women even if not experienced firsthand.13 However, the tendency to self- objectify was strongest when women were personally targeted by the objectifying behavior.14 Most importantly, the researchers’ evidence suggests that experiencing and witnessing sexual objectification in daily life increases body monitoring in women, which, in turn, intensifies women’s experiences of negative and self-conscious emotions.15 Yet, the researchers identified that sexually objectifying events had a short-term psychological impact on women.16 They recognized that these short-term impacts may substantiate the claim from objectification theory that women develop coping skills to minimize the detrimental psychological effects of sexual objectification, which creates resiliency against them.17

In addition, research conducted by Dawn Szymanski and Stacy Henning contended that the psychological consequences of body monitoring—such as reduced concentration, greater body shame, and greater appearance anxiety—lead to depression.18 This research reaffirms the findings of objectification theory and provides further evidence that it is unlikely that the consequences of self-objectification are insignificant or short-term.

Sexual objectification is not an inconsequential phenomenon. The experiences that diminish women to objects inflict and compound psychological distress, especially when the “ideal body” perpetuated by the male gaze is unattainable for most women. In Brit Harper and Marika Tiggemann’s study on the effect that the thin body standard has on women’s well-being, they hypothesized that participants who viewed images featuring a thin idealized woman would demonstrate higher levels of self-objectification, appearance anxiety, negative mood, and body dissatisfaction than participants who viewed the control images.19 The results supported their hypothesis and revealed that even subtle stimuli can induce self-objectification in young women.20 Therefore, it is likely that women self-objectify several times a day.21 They suggest that recurring exposure to media featuring a thin idealized woman could place women at risk of developing depression or eating disorders.22

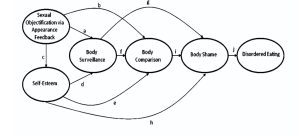

This concept was corroborated by Tracy L. Tylka and Melanie S. Hill’s research on objectification theory and eating disorders. Their study addresses how objectifying messages, such as the societal pressure to be thin, could encourage women to focus more on their appearance and compare their bodies to other women’s. They suggest that this body monitoring and comparison leads to disordered eating.23 When a person negatively comments on a woman’s weight or appearance, it indicates to her that she does not meet the thin-ideal beauty standard. Therefore, for this study, objectification is more broadly referred to as appearance feedback.24 When a woman receives negative appearance feedback, it signals to her that the way to obtain respect from others is to become skinnier.25 Tylka and Hill propose a model that explores how appearance feedback correlates to body surveillance, body comparison, body shame, and low self-esteem, and disordered eating (Fig. 1).26 To investigate these pathways, they had 274 women from a Midwestern U.S. college complete a questionnaire that measured the variables in their model. The data supported each correlation that Tylka and Hill put forward. Furthermore, their research demonstrated that women who frequently monitor their bodies and compare themselves to other women report the highest disordered eating.27

Fig. 1 Tylka and Hill’s proposed model that predicts how appearance feedback leads to body surveillance, body comparison, low self-esteem, and disordered eating.

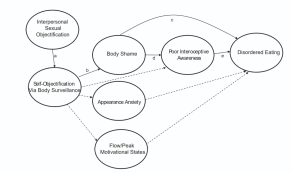

Most of the existing research that has backed the connection between sexual objectification and disordered eating has been conducted with college-aged women.28 Tracy L. Tylka performed another study with Casey L. Augustus-Horvath to explore if this connection was still prevalent for older women. In line with objectification theory, their model proposed that experiencing or witnessing sexual objectification causes a woman to self-objectify. Tylka and Augustus-Horvath posit that self-objectification leads to body shame, poor introspective awareness, and disordered eating (Fig.2).29 In this study, women were placed into two age groups: 18-24 years old and 25-68 years old. The women filled out two survey forms that measured the variables their model projected.30 The data supported their model, upholding that sexual objectification does lead to body shame, poor introspective awareness, and disordered eating for women above 25 years old.31 However, the interactions among variables within the model differed for younger and older women. They concluded that while older women reported lower levels of perceived sexual objectification and body surveillance than younger women, they reported similar levels of body shame, poor introspective awareness, and disordered eating.32 The negative effects of sexual objectification on women’s eating behaviors are not unique to women who meet youthful beauty standards present in the media.33

Fig. 2 Model that illustrates how self-objectification leads to body shame, poor introspective awareness, and disordered eating, as proposed by Tylka and Augustus-Horvath. Dashed lines were not explored in this study.

It is important to acknowledge how sexual objectification affects women with multiple different identities. Fredrickson and Roberts assert that sexual objectification may impact women of color, women at lower socio-economic levels, and lesbians differently because of the additional oppressions they face in addition to being a woman.34 Many of the studies that extend objectification theory only include cisgender women in their data collection, since the theory was originally intended to explain how widespread sexual objectification affects cisgender women’s well-being.35 Future research should explore how sexual objectification impacts transgender and non-binary individuals. Research has been conducted to investigate how the effects of sexual objectification differ for lesbian women. Holly B. Kozee and Tracy L. Tylka assessed whether the variables of objectification theory that predict disordered eating, such as body shame, body surveillance, and lower internal awareness, apply to a sample of lesbian women.36 Lesbian and heterosexual women were split into two groups and were asked to fill out surveys that would quantify facets of objectification theory.37 This study revealed that the data from the heterosexual participants matched the model of objectification theory while data from the lesbian participants did not. The researchers found that lesbian participants had lower levels of disordered eating and greater levels of body surveillance than the heterosexual participants.38 This finding is consistent with objectification theory in that it supports that lesbian women experience the effects of sexual objectification differently than heterosexual women.

Research has also shown that there is a significant difference between how women of color and white women experience the consequences of sexual objectification. As previously noted, objectification theory postulates that rape, sexual assault, and sexual harassment lead directly to depression, eating disorders, and sexual dysfunction. In a 2015 study, researchers found that Black women reported more sexually objectifying experiences and fear of crime than white women.39 This may be attributed to the lack of bodily autonomy that Black women have historically experienced. Researchers also cite overly sexual stereotypes of Black women in culture and media.40 Consequently, as women of color typically experience more sexual objectification due to racism and stereotypes, the mental health impacts are likely to be greater for them.

Violence Against Women

Sexual violence is a form of sexual objectification because a woman is treated as a sexual object that is separated from her humanity.41 To the perpetrator, her body and its sexual functions become more important than her ability to give consent.42 To investigate the connection between violence against women and objectification, Meghan Davidson and Sarah J. Gervais conducted research that explored how sexual violence and intimate partner violence relate to self- objectification, body surveillance, and body shame. Nearly 500 college-aged women took a survey with questions that measured categories and frequency of sexual victimization, psychological and physical abusive behaviors, self-objectification, body surveillance, and body shame.43 The scholars’ research extends objectification theory by contending that objectifying experiences do not have to be inherently sexual. They suggest that the dehumanizing nature of violence within a romantic relationship could predict the effects of objectification.44 Their data indicated a positive correlation between intimate partner violence and self-objectification, body surveillance, and shame. However, regarding sexual violence, there was only a positive correlation between body surveillance and body shame.45 These findings could suggest that the relation between objectification and sexual violence is reversed: objectification leads to sexual violence.

Sarah Eagan and Sarah J. Gervais researched this missing link between sexual objectification and sexual violence. They assert that the ubiquity of objectifying attitudes, especially among men in power, encourages sexual violence against women.46 As their research shows, viewing women as objects is a likely first step toward committing sexual assault or harassment against them.47 There are two ways in which sexual objectification can lead to sexual violence. First, men who objectify women will be more prone to aggression against women. Second, these men can change norms about what is regarded as acceptable and appropriate conduct from men toward women.48 In addition, in our internet-obsessed society, the line between reality and the media is blurred, which contributes to the normalization of objectification.49 The cultural pervasiveness these factors create has direct implications for sexual assault.50 In their lab, the researchers found objectification to be a catalyst for alcohol- related sexual assault.51

To further the conversation about the harmful effects of objectification in the media, Silvia Galdi and Francesca Guizzo put forward the Media-Induced Sexual Harassment framework.52 It illustrates three mechanisms through which sexually objectifying media lead to sexual harassment: the dehumanization of women, decreased empathy with women, and a shift in gender norms.53 The framework then addresses the effects that sexually objectifying media has on the perpetrator, victim, and bystander of sexual harassment.54 In their synthesis of preexisting evidence, they determined that all three of these mechanisms were responsible for the relationship between objectifying media and the perpetrator’s increased likelihood to sexually harass women, as well as a delay in bystander intervention.55 Furthermore, dehumanization and a shift in gender norms correlated to the victim’s increased tolerance for sexual harassment.56 Sexual objectification of women is commonplace in nearly all forms of media, including television, advertisements, music videos, and the internet.57 This framework demonstrates why this is so concerning for women, as it proposes that sexually objectifying media condones sexual harassment and therefore makes it more likely to occur.58

A 2021 study investigated if a video campaign against sexual objectification would reduce male sexual harassment against women. In this experiment, men were shown either a media campaign against female sexual objectification, video clips of a nature documentary, or video clips of sexually objectified women.59 After this, they were given three tasks that would test for three variables: sexually-harassing behavior, hostile sexism, and sexual coercion.60 According to Silvia Galdi and Francesca Guizzo’s data, the media campaign produced the lowest levels of the variables and the sexually objectifying video clips produced the highest.61 The empirical data of this study also suggest that these results are not negligible.62 This study reveals how sensitizing media can be employed to counteract the omnipresence of sexual objectification in the media.63 The timeliness of this study also exemplifies the pressing nature of this conclusion. Intervention is possible at this moment. However, if sexual objectification becomes more pervasive than it is now, sensitizing campaigns may become futile.

The Body Positivity Movement

To reduce the harmful messages about women’s appearance in the media, and the negative impacts they have, the body positivity movement was born. Users on social media began to celebrate realistic and natural representations of women’s bodies. Images depicting women of different shapes, colors, and sizes, with stretch marks, soft stomachs, and other perceived “flaws” challenged the dominant beauty standards.64 The body positivity community was a safe space for women until corporations and influencers took over the movement. A 2021 study looked at how the commodification and reappropriation of the body positivity movement has detrimentally impacted the movement’s purpose.65 Kyla N. Brathwaite and David C. DeAndrea explored how social media users’ ability to recognize when a company or individual uses the body positivity movement to promote their product or platform would impact their perception of the movement itself.66 They asked 851 women to view 10 Instagram posts that were each assigned to one of four conditions: posts with a body-positive message, posts with a body-positive message and self-promotion, corporate-sponsored posts not about appearance, and corporate-sponsored posts about appearance. After viewing these images, the women would then complete a questionnaire.67 The results from the questionnaire illustrated that the more participants recognized the presence of self-promotion or corporate advertising, the less morally appropriate and less effective at promoting body-positivity they viewed the post. However, these conditions less negatively impacted the viewer’ perception if the woman in the post did not adhere to Western beauty ideals.68 This study reveals how body-positive posts from women who conform to ideal body standards and/or contain self-promotion or advertising appear as disingenuous, and therefore less successful at encouraging body appreciation.69

Helana Darwin and Amara Miller’s research also reveals the divisions and shortcomings within the body positivity movement. In their study, they analyzed 50 prominent blog posts from 2014 and 2016 to determine how feminist online spaces are shaped by unequal power dynamics.70 Their investigation found that there are four different frames within the body positivity movement: Mainstream Body Positivity, Fat Positivity = Body Positivity, Radical Body Positivity, and Body Neutrality. The key differences between these frameworks are how advocates believe privilege should be incorporated within the movement, and whether body positivity should focus on individual psychological distress or societal size/race discrimination.71 Mainstream Body Positivity was the most popular frame among the blog posts, and it emphasizes self-love as the solution to the objectification of women. It asserts that the empowerment that comes from feeling and looking beautiful is the solution to body image issues. Many activists are critical of this frame as it reinforces objectification by centering a woman’s worth in her appearance.72 Fat Positivity = Body Positivity was the second most prominent ideology. It advocates for recentering the movement on the systemic discrimination that fat women experience. Individuals disagree with this frame because they find it exclusionary of a multitude of women.73 Radical Body Positivity also agrees that the body positivity movement should focus on systemic oppression, rather than individual concerns about their bodies. It believes that addressing the root causes of size/race oppression will benefit all women. This was the least popular frame among the blog posts.74 Lastly, the Body Neutrality frame accepts anyone who struggles with body image issues, regardless of their social privilege. It encourages women to feel neutral about their appearance, rather than aiming to always feel positive about their bodies.75 These findings elucidate how the body positivity movement is not just nuanced; it is incredibly divisive.76 Because the movement has become polarized and saturated with companies and influencers, the body positivity movement may not be the best solution to deal with the numerous detrimental effects that objectification theory proposes.

Lindsay Kite and Lexie Kite are identical twin sisters who have done groundbreaking work within the body positivity movement with their book More Than a Body: Your Body is an Instrument, Not an Ornament and their nonprofit organization Beauty Redefined. They propose that the solution to the objectification of women is body image resilience.77 Their research employs the idea of resilience as a method to improve body image. They define resilience as “being disrupted by change, opportunities, adversity, stressors or challenges and, after some disorder, accessing personal gifts and strengths to grow stronger through the disruption.”78 The path to body resilience ensues after women experience body image disruptions, such as idealized images in the media or self-comparison.79 They suggest that the first step to body resilience is called “sinking to shame.” This occurs when women experience intense shame that can manifest into harmful behaviors such as disordered eating, self-harm, or drug abuse.80 The second step is “clinging to your comfort zone” in which women try to change their appearance through makeup, clothing, or cosmetic procedures.81 The third and final step is “rising with resilience.” This takes place when a woman acknowledges these body image disruptions, and chooses to rise above them, rather than feeling shameful or trying to change how her body looks.82 Their work is based on the idea that the objectification of women cannot be dismantled because it is so deeply ingrained in society.83

However, I suggest that dismantling is the next step of the body positivity movement. Women are the victims of objectification. They should not be solely responsible for the hard emotional labor of unlearning their self-objectification while society gets to continue to dehumanize them. In a 2010 study, researchers found that women were significantly more likely than men to detect the negative emotions caused by self-objectification.84 They hypothesize that this is due to men’s limited experience with objectifying experiences.85 I argue that educating men and women equally on the dangers of objectification is the most productive way to change the objectifying attitudes present in society.

Introduction to the Curriculum

In this section I propose a curriculum about the objectification of women for students in 7th- and 8th-grade health. The curriculum is built on the information presented in this literature review. Its purpose is to dismantle the objectification of women through the education of future generations. I designed this curriculum to match the methods of instruction that are included in the Utah Core Standards.86 It will consist of two PowerPoint presentations, two videos, two images, one article, one activity, one handout, and one Socratic seminar. In Utah’s Core Standards for education, students complete Health 1 in 7th or 8th grade and Health 2 sometime during 9th-12th grade. There are six strands in Health 1 and 2: Health Foundations and Protective Factors of Healthy Self; Mental and Emotional Health; Safety and Disease Prevention; Substance Abuse Prevention; Nutrition; and Human Development. Each strand is comprised of related topics that mirror each other in the different grade levels. However, the content within the topics changes as the students progress through their education. For example, in the Mental and Emotional Health strand in Health 1, students learn about the risk factors for the development of mental health disorders, and in the Mental and Emotional Health strand in Health 2, students learn how media use can impact their mental health.87

A few strands include topics that pertain to the objectification of women. It would be easy to expand on any one of these areas to include a more in-depth lesson on objectification. In the Nutrition strand in Health 1, students are taught about positive body image. They learn how media and advertisements negatively alter their self-worth. They also learn how to value themselves as a whole person, rather than just as an image. In Health 2, this is mirrored by a lesson plan about eating disorders. In addition, in the Safety and Disease Prevention strand in Health 2, students watch a Dove campaign that shows how women’s images can be heavily

86 “Utah Core Standards – UEN,” accessed March 18, 2022, https://www.uen.org/core/. 87 “Utah Core Standards – UEN.”

distorted. However, this video is utilized to teach about the harmful effects of pornography, not about the harmful effects of objectification. Lastly, in the Safety and Disease Prevention strand in Health 1, students learn about the effects of media and technology on their health. In this lesson plan, students are taught about the differences in how men and women are used in advertising. This lesson plan could function as the perfect segue to teach students specifically about the objectification of women.88

If students learn to identify objectification and understand the harm of it, they will react negatively when they see it employed in advertising and the media. Then, the objectification of women will no longer be profitable for corporations. In addition, objectification will become less prominent on social media if students understand the dangers of objectifying content. To support this, research suggests that encouraging individuals to consider the negative impacts of objectification could lessen the prevalence of sexual objectification in our culture.89

The implementation of this curriculum could potentially lower rates of sexual harassment against women. As aforementioned, researchers found that men were less likely to engage in sexual harassment and sexual coercion after being introduced to the video campaign “Women, Not Objects.” This campaign produced results in mitigating sexual harassment against women, thus it will be included in the curriculum. In the study, researchers showed participants “We Are Not Objects” and “#IStandUp Against the Harm Caused By Objectification of Women in Advertising.” Since these videos feature mature content, students will watch “What Our Kids See” in the curriculum instead. This video reveals how young children internalize objectifying images and how it impacts their perceptions of themselves and others. This is another video from the same campaign, and it ensures the content is appropriate to show in schools.

Background on Objectification for Teachers

This section is a summary of the information presented in this thesis to prepare teachers to lead the lessons on objectification. The definition of objectification for this lesson plan is “when a person is seen or treated as an object.” This curriculum focuses specifically on the sexual objectification of women. Sexual objectification occurs when an individual, typically a woman, is reduced to an object for the sexual gratification of others. Some examples of sexual objectification are catcalling, rating women’s appearances, ogling, sexual comments about women’s bodies, and nonconsensual touch. Women frequently witness sexual objectification in their everyday lives, especially when they consume any form of media. The sexualization of women is widespread in film, magazines, television, music videos, and social media.

According to Objectification Theory by Barbara Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Roberts, when women are exposed to sexually objectifying content or experiences, they impose an outsider’s perspective onto themselves and view themselves as an object. This is known as self- objectification. Fredrickson and Roberts proposed that self-objectification could lead to depression, eating disorders, sexual dysfunction, shame, and reduced concentration in women. This research has been corroborated by numerous studies, some of which suggest that objectification leads to other detrimental effects such as increased violence against women and daily experiences of negative and self-conscious emotions. Research also discusses how the pressure for women to be impossibly thin is a driver of depression and eating disorders.

In the early 2000s, the body positivity movement gained traction on social media sites such as Tumblr and Instagram. The movement, which is a product of the fat rights movement from the 1970s, aims to spread the message that all bodies are beautiful. The movement has been beneficial for women as it helps them deconstruct their self-objectification and provides a sense of community for them. However, the movement has been appropriated by corporations and women who meet the beauty standard. In addition, there are several different branches of body positivity now, resulting in conflict and division within the movement. Body positivity has helped minimize some of the effects of sexual objectification, but it is not the solution to the problem. The solution to the problem is teaching your students why objectification is wrong, and why they should speak out when they see it happening.

Lesson Plan

Title Women, not objects

Subject Author Grade level Time duration Overview

| Title | Women, not objects |

| Subject |

Health |

| Author |

Lauren Lloyd |

|

Grade level |

7-8th |

|

Time duration |

3 class periods, each approximately 45 minutes long. |

| Overview |

In this lesson plan, students will learn how to recognize objectification, the harmful effects of objectification, and how to deconstruct their objectifying attitudes. |

| Objective |

To dismantle the pervasive objectification of women in society by educating students about its detrimental impacts. |

| Materials |

1 handout |

LESSON 1: What is objectification?

Goal:

- To teach students how to recognize objectification .

Materials:

- PowerPoint

- Links to video

- “Objectification in The Media” Handout

Activity:

- True or False game

1. Have students watch What Our Kids See and ask them to share their thoughts on the video.

- “What Our Kids See” by WomenNotObjects (2:04) on YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yBo-G8QRpEo.

2. Show the “What is Objectification” PowerPoint presentation from beginning and ask students to discuss the question on Slide 2.

3. Play “True and False” game on Slide 3-Slide 12. Have students read the statement on the slide and decide whether the answer is true or false. Reveal the answer to the class by clicking again on the slide. If the students answered incorrectly, draw their attention to the explanation provided on the PowerPoint.

4. Have them journal about the questions on the last slide until the end of class.

5. Pass out “Objectification in the Media” assignment. Have students fill it out before the next class.

NAME: ____________________

OBJECTIFICATION IN THE MEDIA

Instructions: Pay attention to the media you consume for a day. See if you find any examples of objectification on TV, on social media, in ads, in a book, in a video game, etc.

- How many examples of objectification did you find? Why were they examples of objectification?

- Where did you find these examples?

- Were you surprised by the number of examples you found?

- Did this activity make you realize anything about yourself/ the media/your peers/society?

WHAT IS OBJECTIFICATION?

“What is Objectification” PowerPoint presentation. What is Objectification.pptx

LESSON 2: Why is objectification harmful? Goal:

- To teach students about the damaging effects of objectification

Materials:

- 2 images

- 1 article

- PowerPoint presentation

- Debrief the “Objectification in the Media” assignment. Ask students to share what they found, and what they took away from the activity.

- Show students the two images for this lesson.

- Have students read “How sexualization of girls creates long-term problems that harm all children” and mark the text.

- “How sexualization of girls creates long-term problems that harm all children” by Lois M. Collins (Sept 17, 2020) from the Deseret News. https://www.deseret.com/indepth/2020/9/17/21432749/media-netflix-cuties- sexualizes-girls-tv-video-games-toys-sexual-harassment-assault.

- Show students “The Harm of Objectification” PowerPoint presentation and have them take notes.

- Ask students to prepare 1 discussion question and 1 potential solution to objectification for the next class.

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/fhsfightback/fhs-fightback-a-feminist-resource-kit- designed-by

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-the-male-gaze-5118422

The Harm of Objectification

“The Harm of Objectification” PowerPoint presentation. The Harm of Objectification.pptx

LESSON 3: What can I do to stop the objectification of women? Goal:

- To encourage students to act against objectification

Materials:

- Link to Video

- Discussion questions

Activity:

- Socratic Seminar

1. Show students Body Positivity or Body Obsession? Learning to See More and Be More. • “Body Positivity or Body Obsession? Learning to See More and Be More” by

Lindsay Kite (16:48) from TEDxSalt Lake City. https://www.ted.com/talks/lindsay_kite_body_positivity_or_body_obsession_lear ning_to_see_more_and_be_more.

2. Put students in small groups for 5-10 minutes and have them discuss the solutions they came up with.

3. Hold Socratic Seminar about the discussion question and solution students brought to class.

Notes

1 Barbara L. Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Roberts, “Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks,” Psychology of Women Quarterly 21, no. 2 (June 1997): 174, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

2 Fredrickson and Roberts, 176–77.

3 Tigress Osborn, “From New York to Instagram: The History of the Body Positivity Movement,” BBC, n.d., https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/z2w7dp3.

4 Erin Nolen, “Is The Body Positivity Social Movement Toxic?,” UT News, December 18, 2019, https://news.utexas.edu/2019/12/18/is-the-body-positivity-social-movement-toxic/.

5 Fredrickson and Roberts, 173.

6 Fredrickson and Roberts, 173.

7 Fredrickson and Roberts, 185-186.

8 Fredrickson and Roberts, 185-186.

9 Fredrickson and Roberts, 188-192.

10 Fredrickson and Roberts, 189- 190.

11 Fredrickson and Roberts, 176-177.

12 Fredrickson and Roberts, 176.

13 Peter Koval et al., “How Does It Feel to Be Treated like an Object? Direct and Indirect Effects of Exposure to Sexual Objectification on Women’s Emotions in Daily Life.,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 116, no. 6 (June 2019): 888-893, https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000161.

14 Koval et al, 893.

15 Koval et al, 894.

16 Koval et al, 895.

17 Koval et al, 895.

18 Dawn M. Szymanski and Stacy L. Henning, “The Role of Self-Objectification in Women’s Depression: A Test of Objectification Theory,” Sex Roles 56, no. 1–2 (February 1, 2007): 51, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9147-3. 19 Brit Harper and Marika Tiggemann, “The Effect of Thin Ideal Media Images on Women’s Self-Objectification, Mood, and Body Image,” Sex Roles 58, no. 9–10 (May 2008): 651, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9379-x.

20 Harper and Tiggemann, 655.

21 Harper and Tiggemann, 655.

22 Harper and Tiggemann, 655.

23 Tracy L. Tylka and Natalie J. Sabik, “Integrating Social Comparison Theory and Self-Esteem within Objectification Theory to Predict Women’s Disordered Eating,” Sex Roles 63, no. 1–2 (July 2010): 18, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9785-3.

24 Tylka and Sabik, 19.

25 Brit Harper and Marika Tiggemann, “The Effect of Thin Ideal Media Images on Women’s Self-Objectification, Mood, and Body Image,” Sex Roles 58, no. 9–10 (May 2008): 19, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9379-x.

26 Tylka and Sabik, 20.

27 Tylka and Sabik, 27.

28 Casey L. Augustus-Horvath and Tracy L. Tylka, “A Test and Extension of Objectification Theory as It Predicts Disordered Eating: Does Women’s Age Matter?,” Journal of Counseling Psychology 56, no. 2 (April 2009): 253, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014637.

29 Augustus-Horvath and Tylka, 254.

30 Augustus-Horvath and Tylka, 256.

31 Augustus-Horvath and Tylka, 261. 32 Augustus-Horvath and Tylka, 262. 33 Augustus-Horvath and Tylka, 261.

34 Fredrickson and Roberts, “Objectification Theory,” 178.

35 Augustus-Horvath and Tylka, “A Test and Extension of Objectification Theory as It Predicts Disordered Eating,” 256.

36 Holly B. Kozee and Tracy L. Tylka, “A Test of Objectification Theory with Lesbian Women,” Psychology of Women Quarterly 30, no. 4 (December 2006): 355, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00310.x.

37 Kozee and Tylka, 351.

38 Kozee and Tylka, 355.

39Laurel B. Watson et al., “Understanding the Relationships Among White and African American Women’s Sexual Objectification Experiences, Physical Safety Anxiety, and Psychological Distress,” Sex Roles 72, no. 3–4 (February 2015): 100, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0444-y..

40 Watson et al., 94-100.

41 M. Meghan Davidson and Sarah J. Gervais, “Violence against Women through the Lens of Objectification Theory,” Violence Against Women 21, no. 3 (March 2015): 334, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801214568031. 42 Davidson and Gervais, 334-35.

43 Davidson and Gervais, 336-40.

44 Davidson and Gervais, 345.

45 Davidson and Gervais, 344.

46 Sarah J. Gervais and Sarah Eagan, “Sexual Objectification: The Common Thread Connecting Myriad Forms of

Sexual Violence against Women.,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 87, no. 3 (2017): 226–32, https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000257.

47 Gervais and Eagan, 230.

48 Gervais and Eagan, 228.

49 Gervais and Eagan, 227.

50 Gervais and Eagan, 228.

51 Gervais and Eagan, 228.

52 Silvia Galdi and Francesca Guizzo, “Media-Induced Sexual Harassment: The Routes from Sexually Objectifying

Media to Sexual Harassment,” Sex Roles 84, no. 11–12 (June 2021): 647, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020- 01196-0.

53 Galdi and Guizzo, 647.

54 Galdi and Guizzo, 647.

55 Galdi and Guizzo, 647.

56 Galdi and Guizzo, 647.

57 Galdi and Guizzo, 647-48. 58 Galdi and Guizzo, 649.

59 Francesca Guizzo and Mara Cadinu, “Women, Not Objects: Testing a Sensitizing Web Campaign against Female Sexual Objectification to Temper Sexual Harassment and Hostile Sexism,” Media Psychology 24, no. 4 (July 4, 2021): 513, https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2020.1756338.

60 Guizzo and Cadinu, 514–19.

61 Guizzo and Cadinu, 531.

62 Guizzo and Cadinu, 529. 63 Guizzo and Cadinu, 531.

64 Kyla N. Brathwaite and David C. DeAndrea, “BoPopriation: How Self-Promotion and Corporate Commodification Can Undermine the Body Positivity (BoPo) Movement on Instagram,” Communication Monographs 89, no. 1 (January 2, 2022): 26–37, https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2021.1925939.

65 Brathwaite and DeAndrea, 43.

66 Brathwaite and DeAndrea, 28–31.

67 Brathwaite and DeAndrea, 31–33.

68 Brathwaite and DeAndrea, 39–40.

69 Brathwaite and DeAndrea, 41.

70 Helana Darwin and Amara Miller, “Factions, Frames, and Postfeminism(s) in the Body Positive Movement,” Feminist Media Studies 21, no. 6 (August 18, 2021): 1, https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1736118.

71 Darwin and Miller, 2. 72 Darwin and Miller, 7.

73 Darwin and Miller, 8–9.

74 Darwin and Miller, 10–11.

75 Darwin and Miller, 11–12.

76 Darwin and Miller, 13.

77 Lexie Kite and Lindsay Kite, More than a Body: Your Body Is an Instrument, Not an Ornament (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021), 10.

78 Kite and Kite, 28.

79 Kite and Kite, 18–19. 80 Kite and Kite, 19–22. 81 Kite and Kite, 23–25. 82 Kite and Kite, 25–29. 83 Kite and Kite, 28.

84 Anna-Kaisa Newheiser, Marianne LaFrance, and John F. Dovidio, “Others as Objects: How Women and Men Perceive the Consequences of Self-Objectification,” Sex Roles 63, no. 9–10 (November 2010): 668, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9879-y.

85 Newheiser, LaFrance, and Dovidio, 658.

88 “Utah Core Standards – UEN.”

89 Newheiser, LaFrance, and Dovidio, “Others as Objects,” 668.

Bibliography

Augustus-Horvath, Casey L., and Tracy L. Tylka. “A Test and Extension of Objectification Theory as It Predicts Disordered Eating: Does Women’s Age Matter?” Journal of Counseling Psychology 56, no. 2 (April 2009): 253–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014637.

Brathwaite, Kyla N., and David C. DeAndrea. “BoPopriation: How Self-Promotion and Corporate Commodification Can Undermine the Body Positivity (BoPo) Movement on Instagram.” Communication Monographs 89, no. 1 (January 2, 2022): 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2021.1925939.

Darwin, Helana, and Amara Miller. “Factions, Frames, and Postfeminism(s) in the Body Positive Movement.” Feminist Media Studies 21, no. 6 (August 18, 2021): 873–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1736118.

Fredrickson, Barbara L., and Tomi-Ann Roberts. “Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 21, no. 2 (June 1997): 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471- 6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Gervais, Sarah J., and Sarah Eagan. “Sexual Objectification: The Common Thread Connecting Myriad Forms of Sexual Violence against Women.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 87, no. 3 (2017): 226–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000257.

Harper, Brit, and Marika Tiggemann. “The Effect of Thin Ideal Media Images on Women’s Self- Objectification, Mood, and Body Image.” Sex Roles 58, no. 9–10 (May 2008): 649–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9379-x.

Kite, Lexie, and Lindsay Kite. More than a Body: Your Body Is an Instrument, Not an Ornament. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021.

Kozee, Holly B., and Tracy L. Tylka. “A Test of Objectification Theory with Lesbian Women.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 30, no. 4 (December 2006): 348–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00310.x.

Newheiser, Anna-Kaisa, Marianne LaFrance, and John F. Dovidio. “Others as Objects: How Women and Men Perceive the Consequences of Self-Objectification.” Sex Roles 63, no. 9–10 (November 2010): 657–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9879-y.

Nolen, Erin. “Is The Body Positivity Social Movement Toxic?” UT News, December 18, 2019. https://news.utexas.edu/2019/12/18/is-the-body-positivity-social-movement-toxic/.

Osborn, Tigress. “From New York to Instagram: The History of the Body Positivity Movement.” BBC, n.d. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/z2w7dp3.

Tylka, Tracy L., and Natalie J. Sabik. “Integrating Social Comparison Theory and Self-Esteem within Objectification Theory to Predict Women’s Disordered Eating.” Sex Roles 63, no. 1–2 (July 2010): 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9785-3.

“Utah Core Standards – UEN.” https://www.uen.org/core/.