57 Reaction Stoichiometry

LumenLearning

Amount of Reactants and Products

Stoichiometry is the study of the relative quantities of reactants and products in chemical reactions and how to calculate those quantities.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Construct a balanced chemical equation

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- To fully understand a chemical reaction, a balanced chemical equation must be written.

- Chemical reactions are balanced by adding coefficients so that the number of atoms of each element is the same on both sides.

- Stoichiometry describes the relationship between the amounts of reactants and products in a reaction.

Key Terms

- stoichiometry: The field of chemistry that is concerned with the relative quantities of reactants and products in chemical reactions and how to calculate those quantities.

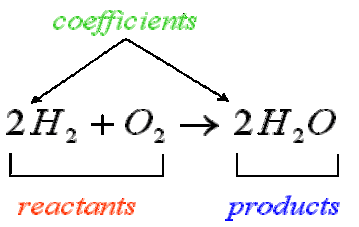

Chemical equations are symbolic representations of chemical reactions. The reacting materials (reactants) are given on the left, and the products are displayed on the right, usually separated by an arrow showing the direction of the reaction. The numerical coefficients next to each chemical entity denote the proportion of that chemical entity before and after the reaction. The law of conservation of mass dictates that the quantity of each element must remain unchanged in a chemical reaction. Therefore, in a balanced equation each side of the chemical equation must have the same quantity of each element.

Stoichiometry

Stoichiometry is the field of chemistry that is concerned with the relative quantities of reactants and products in chemical reactions. For any balanced chemical reaction, whole numbers (coefficients) are used to show the quantities (generally in moles ) of both the reactants and products. For example, when oxygen and hydrogen react to produce water, one mole of oxygen reacts with two moles of hydrogen to produce two moles of water.

In addition, stoichiometry can be used to find quantities such as the amount of products that can be produced with a given amount of reactants and percent yield. Upcoming concepts will explain how to calculate the amount of products that can be produced given certain information.

The relationship between the products and reactants in a balanced chemical equation is very important in understanding the nature of the reaction. This relationship tells us what materials and how much of them are needed for a reaction to proceed. Reaction stoichiometry describes the quantitative relationship among substances as they participate in various chemical reactions.

Molar Ratios

Molar ratios, or conversion factors, identify the number of moles of each reactant needed to form a certain number of moles of each product.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Calculate the molar ratio between two substances given their balanced reaction

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- Molar ratios state the proportions of reactants and products that are used and formed in a chemical reaction.

- Molar ratios can be derived from the coefficients of a balanced chemical equation.

- Stoichiometric coefficients of a balanced equation and molar ratios do not tell the actual amounts of reactants consumed and products formed.

Key Terms

- stoichiometric ratio: The ratio of the coefficients of the products and reactants in a balanced reaction. This ratio can be used to calculate the amount of products or reactants produced or used in a reaction.

Chemical equations are symbolic representations of chemical reactions. In a chemical equation, the reacting materials are written on the left, and the products are written on the right; the two sides are usually separated by an arrow showing the direction of the reaction. The numerical coefficient next to each entity denotes the absolute stoichiometric amount used in the reaction. Because the law of conservation of mass dictates that the quantity of each element must remain unchanged over the course of a chemical reaction, each side of a balanced chemical equation must have the same quantity of each particular element.

In a balanced chemical equation, the coefficients can be used to determine the relative amount of molecules, formula units, or moles of compounds that participate in the reaction. The coefficients in a balanced equation can be used as molar ratios, which can act as conversion factors to relate the reactants to the products. These conversion factors state the ratio of reactants that react but do not tell exactly how much of each substance is actually involved in the reaction.

Determining Molar Ratios

The molar ratios identify how many moles of product are formed from a certain amount of reactant, as well as the number of moles of a reactant needed to completely react with a certain amount of another reactant. For example, look at this equation:

[latex]\text{CH}_4 + \text{2O}_2 \rightarrow \text{CO}_2 + \text{2H}_2\text{O}[/latex]

From this reaction equation, it is possible to deduce the following molar ratios:

- 1 mol [latex]\text{CH}_4[/latex]: 1 mol [latex]\text{CO}_2[/latex]

- 1 mol [latex]\text{CH}_4[/latex]: 2 mol [latex]\text{H}_2\text{O}[/latex]

- 1 mol [latex]\text{CH}_4[/latex]: 2 mol [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex]

- 2 mol [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex]: 1 mol [latex]\text{CO}_2[/latex]

- 2 mol [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex]: 2 mol [latex]\text{H}_2\text{O}[/latex]

In other words, 1 mol of methane will produced 1 mole of carbon dioxide (as long as the reaction goes to completion and there is plenty of oxygen present). These molar ratios can also be expressed as fractions. For example, 1 mol [latex]\text{CH}_4[/latex]: 1 mol [latex]\text{CO}_2[/latex] can be expressed as [latex]\frac{\text{1 mol CH}_4}{\text{1 mol CO}_2}[/latex].These molar ratios will be very important for quantitative chemistry calculations that will be discussed in later concepts.

Mole-to-Mole Conversions

Mole-to-mole conversions can be facilitated by using conversion factors found in the balanced equation for the reaction of interest.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Calculate how many moles of a product are produced given quantitative information about the reactants.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- The law of conservation of mass dictates that the quantity of an element does not change over the course of a reaction. Therefore, a chemical equation is balanced when all elements have equal values on both the left and right sides.

- The balanced equation for the reaction of interest contains the stoichiometric ratios of the reactants and products; these ratios can be used as conversion factors for mole -to-mole conversions.

- Stoichiometric ratios are unique for each chemical reaction.

Key Terms

- conversion factor: A ratio of coefficients found in a balanced reaction, which can be used to inter-convert the amount of products and reactants.

- mole: In the International System of Units, the base unit of the amount of substance; the amount of substance of a system that contains as many elementary entities as there are atoms in 12 g of carbon-12.

Stoichiometric Values in a Chemical Reaction

A chemical equation is a visual representation of a chemical reaction. In a typical chemical equation, an arrow separates the reactants on the left and the products on the right. The coefficients next to the reactants and products are the stoichiometric values. They represent the number of moles of each compound that needs to react so that the reaction can go to completion.

On some occasions, it may be necessary to calculate the number of moles of a reagent or product under certain reaction conditions. To do this correctly, the reaction needs to be balanced. The law of conservation of matter states that the quantity of each element does not change in a chemical reaction. Therefore, a chemical equation is balanced when the number of each element in the equation is the same on both the left and right sides of the equation.

Using Stoichiometry to Calculate Moles

The next step is to inspect the coefficients of each element of the equation. The coefficients can be thought of as the amount of moles used in the reaction. The key is reaction stoichoimetry, which describes the quantitative relationship among the substances as they participate in the chemical reaction. The relationship between two of the reaction’s participants (reactant or product) can be viewed as conversion factors and can be used to facilitate mole-to-mole conversions within the reaction.

EXAMPLE 1

For example, to determine the number of moles of water produced from 2 mol [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex], the balanced chemical reaction should be written out:

[latex]\text{2H}_2 (g) + \text{O}_2(g) \rightarrow \text{2H}_2\text{O}(g)[/latex]

There is a clear relationship between [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex] and [latex]\text{H}_2\text{O}[/latex]: for every one mole of [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex], two moles of [latex]\text{H}_2\text{O}[/latex] are produced. Therefore, the ratio is one mole of [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex] to two moles of [latex]\text{H}_2\text{O}[/latex], or [latex]\frac{\text{1 mol O}_2}{\text{2 moles H}_2 \text{O}}[/latex]. Assume abundant hydrogen and two moles of [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex], then one can calculate:

[latex]\text{2 moles O}_2 \cdot \frac{\text{2 mol H}_2\text{O}}{\text{1 mol O}_2} = \text{4 moles H}_2\text{O}[/latex]

Therefore, 4 moles of [latex]\text{H}_2\text{O}[/latex] were produced by reacting 2 moles of [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex] in excess hydrogen.

Each stoichiometric conversion factor is reaction-specific and requires that the reaction be balanced. Therefore, each reaction must be balanced before starting calculations.

EXAMPLE 2

If 4.44 mol of [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex] react with excess hydrogen, how many moles of water are produced?

The chemical equation is [latex]\text{O}_2 + \text{2H}_2 \rightarrow \text{2H}_2\text{O}[/latex]. Therefore, to calculate the number of moles of water produced:

[latex]\text{4.44 mol O}_2 \cdot \frac{\text{2 moles H}_2\text{O}}{\text{1 mol O}_2} = \text{8.88 moles H}_2\text{O}[/latex]

Stoichiometry: Moles to Moles – YouTube: This video shows how to determine the number of moles of reactants and products using the number of moles of one of the substances in the reaction.

Mass-to-Mass Conversions

Mass-to-mass conversions cannot be done directly; instead, mole values must serve as intermediaries in these conversions.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Calculate the mass of reactants and products from a balanced chemical equation and information about the amount of reactant(s) present.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- The law of conservation of mass dictates that the quantity of an element does not change over the course of the reaction. Therefore, a chemical equation is balanced when each element has equal numbers on both the left and right sides of the equation.

- Stoichiometric ratios, the ratios of the amounts of each substance used, are unique for each chemical reaction.

- The balanced equation of a reaction contains the stoichiometric ratios of the reactants and products; these ratios can be used for mole -to-mole conversions. There is no direct way to convert from the mass of one substance to the mass of another.

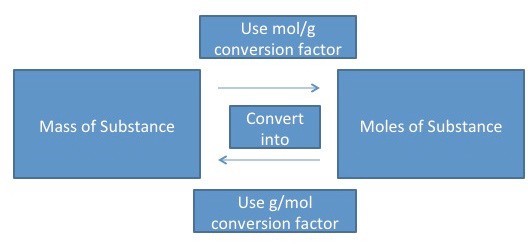

- To convert from one mass (substance A) to another mass (substance B), you must convert the mass of A first to moles, then use the mole-to-mole conversion factor (B/A), then convert the mole amount of B back to grams of B.

Key Terms

- stoichiometric ratio: The quantitative ratio between the reactants and products of a specific reaction or chemical equation. The ratio is made up of their coefficients from the balanced equation.

A chemical equation is a visual representation of a chemical reaction. A typical chemical equation follows the form

[latex]aA + bB \rightarrow cC + dD[/latex]

where an arrow separates the reactants on the left and the products on the right. The coefficients before the reactants and products are their stoichiometric values.

Calculating the Mass of Reactants & Products

One may need to compute the mass of a reactant or product under certain reaction conditions. To do this, it is necessary to ensure that the reaction is balanced. The ratio of the coefficients of two of the compounds in a reaction (reactant or product) can be viewed as a conversion factor and can be used to facilitate mole-to-mole conversions within the reaction. It is not possible to directly convert from the mass of one element to the mass of another. Therefore, for a mass-to-mass conversion, it is necessary to first convert one amount to moles, then use the conversion factor to find moles of the other substance, and then convert the molar value of interest back to mass.

EXAMPLE

This can be illustrated by the following example, which calculates the mass of oxygen needed to burn 54.0 grams of butane [latex]\text{(C}_4\text{H}_{10} )[/latex]. The balanced equation is:

[latex]\text{2C}_4\text{H}_{10} + \text{13O}_2 \rightarrow \text{8CO}_2 + \text{10H}_2\text{O}[/latex]

Because there is no direct way to compare the mass of butane to the mass of oxygen, the mass of butane must be converted to moles of butane:

[latex]\text{54.0 g C}_4\text{H}_{10} \cdot \frac{\text{1 mol}}{\text{58.1 g}} = \text{0.929 mol C}_4\text{H}_{10}[/latex]

With the number of moles of butane equal to 54 grams, it is possible to find the moles of [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex] that can react with it. Taking coefficients from the reaction equation [latex]\text{(13 O}_2[/latex] and [latex]\text{2 C}_4\text{H}_{10})[/latex], the molar ratio of [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex] to [latex]\text{C}_4\text{H}_{10}[/latex] is 13:2.

[latex]\text{0.929 mol C}_4\text{H}_{10} \cdot \frac{\text{13 mol O}_2}{\text{2 mol C}_4\text{H}_{10}} = \text{6.05 mol O}_2[/latex]

This last equation shows that 6.05 moles of [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex] can react with 0.929 moles of [latex]\text{C}_4\text{H}_{10}[/latex]. The molar amount of [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex] can now be easily converted back to grams of oxygen:

[latex]\text{6.05 mol} \cdot \frac{\text{32 g}}{\text{1 mol}} = \text{193 g O}_2[/latex]

In summary, it was impossible to directly determine the mass of oxygen that could react with 54.0 grams of butane. But by converting the butane mass to moles (0.929 moles) and using the molar ratio (13 moles oxygen: 2 moles butane), one can find the molar amount of oxygen (6.05 moles) that reacts with 54.0 grams of butane. Using the molar amount of oxygen, it is then possible to find the mass of the oxygen (193 g).

Stoichiometry: Grams to Grams – YouTube: This video shows how to determine the grams of the other substances in the chemical equation if the grams of one of the substances is known

Mass-to-Mole Conversions

Mass-to-mole conversions can be facilitated by employing the molar mass as a conversion ratio.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Convert from grams to moles using a compound’s molar mass.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

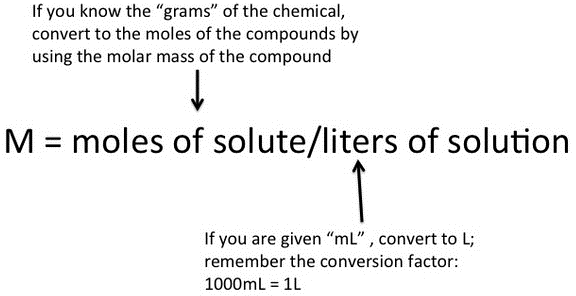

- The mole is the universal measurement of quantity in chemistry. Although it is not possible to directly measure how many moles a substance contains, it is possible to first measure its mass and then convert that amount to moles.

- A substance’s molar mass is calculated by multiplying its relative atomic mass by the molar mass constant (1 g/mol).

- The molar mass constant can be used to convert mass to moles. By multiplying a given mass by the molar mass, the amount of moles of the substance can be calculated.

Key Terms

- molar mass: The mass of a given substance (chemical element or chemical compound) divided by its amount (mol) of substance.

- mole: In the International System of Units, the base unit of the amount of substance; the amount of substance of a system that contains as many elementary entities as there are atoms in 12 g of carbon-12.

The mole is the universal measurement of quantity in chemistry. However, the measurements that researchers take every day provide answers not in moles but in more physically concrete units, such as grams or milliliters. Therefore, scientists need some way of comparing what can be physically measured to the amount of measurement they are interested in: moles.

Converting Grams to Moles

The compound ‘s molar mass is necessary when converting from grams to moles. The molar mass value can be used as a conversion factor to facilitate mass-to-mole and mole-to-mass conversions.

- For a single element, the molar mass is equivalent to its atomic weight multiplied by the molar mass constant (1 g/mol).

- For a compound, the molar mass is the sum of the atomic weights of each element in the compound multiplied by the molar mass constant.

After the molar mass is determined, dimensional analysis can be used to convert from grams to moles.

EXAMPLE 1

For example, convert 18 grams of water to moles of water. The molar mass of water is 18 g/mol. Therefore:

[latex]\text{18 g H}_2\text{O} \times \frac{\text{1 mol}}{\text{18 g H}_2\text{O}} = \text{1.0 mol H}_2\text{O}[/latex]

EXAMPLE 2

If you have 34.5 g of [latex]\text{NaCl}[/latex], how many moles of [latex]\text{NaCl}[/latex] do you have?

[latex]\text{34.5 g NaCl} \times \frac{\text{1 mol NaCl}}{\text{58.4 g NaCl}} = \text{0.591 moles NaCl}[/latex]

Stoichiometry, Grams to Moles – YouTube: This video describes how to determine the number of moles of reactants and products if given the number of grams of one of the substances in the chemical equation.

Limiting Reagents

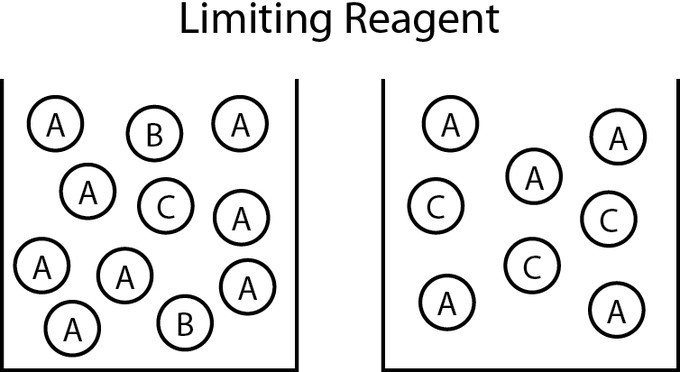

The reagent that limits how much product is produced (the reactant that runs out first) is known as the limiting reagent.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Determine the limiting reagent and the amount of a product formed in a given reavion

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- The limiting reagent is the reactant that is used up completely. This stops the reaction and no further products are made.

- Given the balanced chemical equation that describes the reaction, there are several ways to identify the limiting reagent.

- One way to determine the limiting reagent is to compare the mole ratios of the amounts of reactants used. This method is most useful when there are only two reactants.

- The limiting reagent can also be derived by comparing the amount of products that can be formed from each reactant.

Key Terms

- limiting reagent: The reactant in a chemical reaction that is consumed first; prevents any further reaction from occurring.

In a chemical reaction, the limiting reagent, or limiting reactant, is the substance that has been completely consumed when the chemical reaction is complete. The amount of product produced by the reaction is limited by this reactant because the reaction cannot proceed further without it; often, other reagents are present in excess of the quantities required to to react with the limiting reagent. From stoichiometry, the exact amount of reactant needed to react with another element can be calculated. However, if the reagents are not mixed or present in these correct stoichiometric proportions, the limiting reagent will be entirely consumed and the reaction will not go to stoichiometric completion.

Determining the Limiting Reagent

One way to determine the limiting reagent is to compare the mole ratio of the amount of reactants used. This method is most useful when there are only two reactants. One reactant (A) is chosen, and the balanced chemical equation is used to determine the amount of the other reactant (B) necessary to react with A. If the amount of B actually present exceeds the amount required, then B is in excess, and A is the limiting reagent. If the amount of B present is less than is required, then B is the limiting reagent.

To begin, the chemical equation must first be balanced. The law of conservation states that the quantity of each element does not change over the course of a chemical reaction. Therefore, the chemical equation is balanced when the amount of each element is the same on both the left and right sides of the equation. Next, convert all given information (typically masses) into moles, and compare the mole ratios of the given information to those in the chemical equation.

For example: What would be the limiting reagent if 75 grams of [latex]\text{C}_2\text{H}_3\text{Br}_3[/latex] reacted with 50.0 grams of [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex] in the following reaction:

[latex]\text{4C}_2\text{H}_3\text{Br}_3 + \text{11O}_2 \rightarrow \text{8CO}_2 + \text{6H}_2\text{O} + \text{6Br}_2[/latex]

First, convert the values to moles:

[latex]\text{75 g} \times \frac{\text{1 mol}}{\text{266.72 g}} = \text{0.28 mol C}_2\text{H}_3\text{Br}_3[/latex]

[latex]\text{50.0 g} \times \frac{\text{1 mol}}{\text{32 g}} = \text{1.56 mol O}_2[/latex]

It is then possible to calculate how much [latex]\text{C}_2\text{H}_3\text{Br}_3[/latex] would be required if all the [latex]\text{O}_2[/latex] is used up:

[latex]\text{1.56 mol O}_2 \times \frac{\text{4 mol C}_2\text{H}_3\text{Br}_3}{\text{11 mol O}_2} = \text{0.567 mol C}_2\text{H}_3\text{Br}_3[/latex]

This demonstrates that 0.567 mol [latex]\text{C}_2\text{H}_3\text{Br}_3[/latex] is required to react with all the oxygen. Since there is only 0.28 mol [latex]\text{C}_2\text{H}_3\text{Br}_3[/latex] present, [latex]\text{C}_2\text{H}_3\text{Br}_3[/latex] is the limiting reagent.

Another method of determining the limiting reagent involves the comparison of product amounts that can be formed from each reactant. This method can be extended to any number of reactants more easily than the previous method. Again, begin by balancing the chemical equation and by converting all the given information into moles. Then use stoichiometry to calculate the mass of the product that could be produced for each individual reactant. The reactant that produces the least amount of product is the limiting reagent.

For example: What would be the limiting reagent if 80.0 grams of [latex]\text{Na}_2\text{O}_2[/latex] reacted with 30.0 grams of [latex]\text{H}_2\text{O}[/latex] in the reaction?

[latex]\text{2Na}_2\text{O}_2 + \text{2H}_2\text{O} \rightarrow \text{4NaOH} + \text{O}_2[/latex]

The comparison can be done with either product; for this example, [latex]\text{NaOH}[/latex] will be the product compared. To determine how much [latex]\text{NaOH}[/latex] is produced by each reagent, use the stoichiometric ratio given in the chemical equation as a conversion factor:

[latex]\frac{\text{4 mol NaOH}}{\text{2 mol Na}_2\text{O}_2}[/latex] and [latex]\frac{\text{4 mol NaOH}}{\text{2 mol H}_2\text{O}}[/latex]

Then convert the grams of each reactant into moles of [latex]\text{NaOH}[/latex] to see how much [latex]\text{NaOH}[/latex] each could produce if the other reactant was in excess.

[latex]\text{80.0 g Na}_2\text{O}_2 \times \frac{\text{1 mol Na}_2\text{O}_2}{\text{77.98 g Na}_2\text{O}_2} \times \frac{\text{4 mol NaOH}}{\text{2 mol Na}_2\text{O}_2} = \text{2.06 moles NaOH}[/latex]

[latex]\text{30.0 g H}_2\text{O} \times \frac{\text{1 mol H}_2\text{O}}{\text{18 g H}_2\text{O}} \times \frac{\text{4 mol NaOH}}{\text{2 mol H}_2\text{O}} = \text{3.33 moles NaOH}[/latex]

Obviously the [latex]\text{Na}_2\text{O}_2[/latex] produces less [latex]\text{NaOH}[/latex] than [latex]\text{H}_2\text{O}[/latex]; therefore, [latex]\text{Na}_2\text{O}_2[/latex] is the limiting reagent.

STOICHIOMETRY – Limiting Reactant & Excess Reactant Stoichiometry & Moles – YouTube: A video showing two examples of how to solve limiting reactant stoichiometry problems. This video also explains how to determine the excess reactant too.

Calculating Theoretical and Percent Yield

The percent yield of a reaction measures the reaction’s efficiency. It is the ratio between the actual yield and the theoretical yield.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Calculate the percent yield of a reaction, distinguishing from theoretical and actual yield.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- The theoretical yield for a reaction is calculated based on the limiting reagent. This allows researchers to determine how much product can actually be formed based on the reagents present at the beginning of the reaction.

- The actual yield will never be 100 percent due to limitations.

- [latex]\text{Percent yield} = \frac{\text{actual yield}}{\text{theoretical yield}} \times 100[/latex]. Percent yield measures how efficient the reaction is under certain conditions.

Key Terms

- actual yield: The amount of product actually obtained in a chemical reaction.

- percent yield: Refers to the efficiency of a chemical reaction; defined as the [latex]\frac{\text{actual yield}}{\text{theoretical yield}} \times 100[/latex]

- theoretical yield: The amount of product that could possibly be produced in a given reaction, calculated according to the starting amount of the limiting reagent.

In chemistry, it is often important to know how efficient a reaction is. This is because when a reaction is carried out, the reactants may not always be present in the proportions written in the balanced equation. As a result, some of the reactants will be used, and some will be left over when the reaction is completed.

Theoretical, Actual, and Percents Yields

A reaction should theoretically produce as much of the product as the stoichiometric ratio of product to the limiting reagent suggests. This number can be calculated and is called the theoretical yield. However, the amount of product actually produced by the reaction will usually be less than the theoretical yield and is referred to as the actual yield. This is because often reactions have “side reactions” that compete for reactants and produce undesired products. To evaluate the efficiency of the reaction, chemists compare the theoretical and actual yields by calculating the percent yield of a reaction:

[latex]\text{Percent yield} = \frac{\text{actual yield}}{\text{theoretical yield}} \times 100[/latex]

To calculate percent yield using this equation, it is not necessary to use a particular unit of measurement (moles, mL, g etc.), but it is important that the two values being compared are consistent in units. The theoretical yield of a reaction is 100 percent, but this value becomes nearly impossible to achieve due to limitations.

To accurately calculate the yield, the equation needs to be balanced. Next, identify the limiting reagent. Then the theoretical yield of the product can be determined and, finally, compared to the actual yield. Then, percent yield can be calculated.

For example, consider the preparation of nitrobenzene [latex]\text{(C}_6\text{H}_5\text{NO}_2)[/latex], starting with 15.6g of benzene [latex]\text{(C}_6\text{H}_6)[/latex] in excess of nitric acid [latex]\text{(HNO}_3 )[/latex]:

[latex]\text{C}_6\text{H}_6 + \text{HNO}_3 \rightarrow \text{C}_6\text{H}_5\text{NO}_2 + \text{H}_2\text{O}[/latex]

[latex]\text{15.6 g C}_6\text{H}_6 \times \frac{\text{1 mol C}_6\text{H}_6}{\text{78.1 g C}_6\text{H}_6} \times \frac{\text{1 mol C}_6\text{H}_5\text{NO}_2}{\text{1 mol C}_6\text{H}_6} \times \frac{\text{123.1 g C}_6\text{H}_5\text{NO}_2}{\text{1 mol C}_6\text{H}_5\text{NO}_2} \ = \text{24.6 g C}_6\text{H}_5\text{NO}_2[/latex]

In theory, therefore, if all [latex]\text{C}_6\text{H}_6[/latex] were converted to product and isolated, 24.6 grams of product would be obtained (100 percent yield). If 18.0 grams were actually produced, the percent yield could be calculated:

percent yield = [latex]\frac{\text{48.0 g}}{\text{24.6 g}} \times 100[/latex]

percent yield = 73.2%

Limiting Reactants and Percent Yield – YouTube: This video explains the concept of a limiting reactant (or a limiting reagent) in a chemical reaction. It also shows how to calculate the limiting reactant and the percent yield in a chemical reaction.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SPECIFIC ATTRIBUTION

- Stoichiometry. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoichiometry. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- stoichiometry. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/stoichiometry. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chemistry11MrStandring - Chemical Equations and the Conservation Laws. Provided by: Wikispaces. Located at: https://chemistry11mrstandring.wikispaces.com/Chemical+Equations+and+the+Conservation+Laws. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Stoichiometry. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoichiometry. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chemical equations. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemical_equations. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- stoichiometric ratio. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/stoichiometric%20ratio. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chemistry11MrStandring - Chemical Equations and the Conservation Laws. Provided by: Wikispaces. Located at: https://chemistry11mrstandring.wikispaces.com/Chemical+Equations+and+the+Conservation+Laws. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chemical equation. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemical_equation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- mole. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/mole. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chemistry11MrStandring - Chemical Equations and the Conservation Laws. Provided by: Wikispaces. Located at: https://chemistry11mrstandring.wikispaces.com/Chemical+Equations+and+the+Conservation+Laws. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Stoichiometry: Moles to Moles - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qRVUNCw9fOY. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- stoichiometric ratio. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/stoichiometric%20ratio. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chemistry11MrStandring - Chemical Equations and the Conservation Laws. Provided by: Wikispaces. Located at: https://chemistry11mrstandring.wikispaces.com/Chemical+Equations+and+the+Conservation+Laws. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Stoichiometry: Moles to Moles - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qRVUNCw9fOY. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Boundless. Provided by: Amazon Web Services. Located at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/figures.boundless.com/50a45d28e4b0b85f2f141b92/Slide2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Stoichiometry: Grams to Grams - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bltnuzbs2JA. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Atomic weight. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atomic_weight. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- molar mass. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/molar%20mass. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- mole. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/mole. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chemistry11MrStandring - Chemical Equations and the Conservation Laws. Provided by: Wikispaces. Located at: https://chemistry11mrstandring.wikispaces.com/Chemical+Equations+and+the+Conservation+Laws. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Stoichiometry: Moles to Moles - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qRVUNCw9fOY. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Boundless. Provided by: Amazon Web Services. Located at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/figures.boundless.com/50a45d28e4b0b85f2f141b92/Slide2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Stoichiometry: Grams to Grams - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bltnuzbs2JA. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Stoichiometry, Grams to Moles - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=09g6nN2PpVE. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Boundless. Provided by: Amazon Web Services. Located at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/figures.boundless.com/50a45d8de4b0b85f2f141b9e/Slide3.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Limiting reagent. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limiting_reagent. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- limiting reagent. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/limiting%20reagent. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chemistry11MrStandring - Chemical Equations and the Conservation Laws. Provided by: Wikispaces. Located at: https://chemistry11mrstandring.wikispaces.com/Chemical+Equations+and+the+Conservation+Laws. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Stoichiometry: Moles to Moles - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qRVUNCw9fOY. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Boundless. Provided by: Amazon Web Services. Located at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/figures.boundless.com/50a45d28e4b0b85f2f141b92/Slide2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Stoichiometry: Grams to Grams - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bltnuzbs2JA. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Stoichiometry, Grams to Moles - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=09g6nN2PpVE. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Boundless. Provided by: Amazon Web Services. Located at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/figures.boundless.com/50a45d8de4b0b85f2f141b9e/Slide3.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- STOICHIOMETRY - Limiting Reactant & Excess Reactant Stoichiometry & Moles - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qLUJdF_l8LA. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Limiting Reagent. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Limiting_Reagent.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Theoretical yield. Provided by: WIKIPEDIA. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theoretical_yield. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- percent yield. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/percent%20yield. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Yield (chemistry). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yield_(chemistry). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: http://www.boundless.com//chemistry/definition/theoretical-yield. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chemistry11MrStandring - Chemical Equations and the Conservation Laws. Provided by: Wikispaces. Located at: https://chemistry11mrstandring.wikispaces.com/Chemical+Equations+and+the+Conservation+Laws. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Stoichiometry: Moles to Moles - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qRVUNCw9fOY. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Boundless. Provided by: Amazon Web Services. Located at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/figures.boundless.com/50a45d28e4b0b85f2f141b92/Slide2.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Stoichiometry: Grams to Grams - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bltnuzbs2JA. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Stoichiometry, Grams to Moles - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=09g6nN2PpVE. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Boundless. Provided by: Amazon Web Services. Located at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/figures.boundless.com/50a45d8de4b0b85f2f141b9e/Slide3.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- STOICHIOMETRY - Limiting Reactant & Excess Reactant Stoichiometry & Moles - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qLUJdF_l8LA. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

- Limiting Reagent. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Limiting_Reagent.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Limiting Reactants and Percent Yield - YouTube. Located at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LicEaaXhlEY. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

This chapter is an adaptation of the chapter "Reaction Stoichiometry" in Boundless Chemistry by LumenLearning and is licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

the study and calculation of quantitative (measurable) relationships of the reactants and products in chemical reactions (chemical equations)

the mass of one mole of an element or compound