The Digestive System

Only [Med Terms] in the Building Episode 10

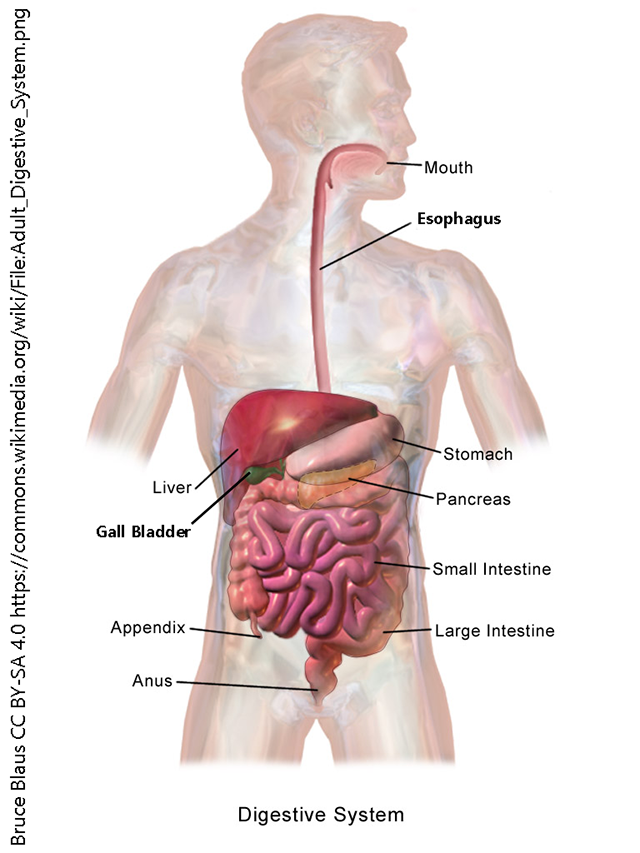

The digestive system has but a single overarching function: to take in food, break it down into nutrients that are absorbed by the stomach and intestines, and then excrete any leftover waste as feces.

In order to accomplish this complex function, the digestive system has two basic subdivisions: the gastrointestinal tract and the accessory organs.

Gastrointestinal tract organs include:

- mouth

- pharynx

- oropharynx

- laryngopharyx

- esophagus

- stomach

- small intestine

- duodenum

- jejunum

- ileum

- large intestine

- [vermiform] appendix

- cecum

- ascending colon

- transverse colon

- descending colon

- sigmoid colon

- rectum

- anus

Accessory organs include:

- teeth

- tongue

- salivary glands

- liver

- gall bladder

- pancreas

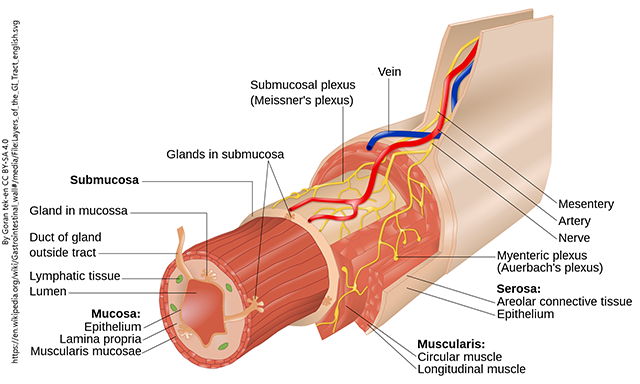

In keeping with its straightforward function, the microscopic structure of the stomach and intestines are almost identical throughout the gut tube. There are variations, for example, the addition of acid secreting cells in the stomach, and the specializations involved in extracting water in the large intestine, but the basic structure is the same, as shown in the diagram below.

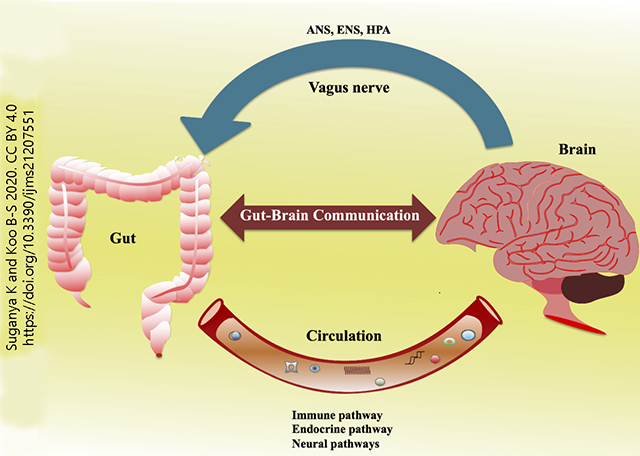

In this diagram, note the presence of two plexi: the submucosal plexus (Meissner’s plexus) and the myenteric plexus (Auerbach’s plexus). The structures are part of an important control system: the enteric nervous system. There is semi-independent control of gut functions (such as peristalsis, the milking action of the gut wall that moves substances from esophagus to anus). The enteric nervous system (ENS) both receives signals from, and sends signals to, the central nervous system and the autonomic nervous system (ANS: the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions we studied in Unit 6). The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis sends information to the gut as well. These nerve signals primarily travel along the tenth cranial nerve, the vagus nerve. The immune system also contributes to, and is affected by, the function of the gut. Finally, there is a gut microbiome, consisting of all the bacteria which exist in a cooperative relationship with the human cells. For example, bacteria make vitamin K, a clotting factor that cannot be made by human cells. All these relationships are encompassed in the gut-brain-immune pathways diagrammed here.

Media Attributions

- Unit 10 figure 1 Digestive System © Bruce Blaus is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Unit 10 figure 2 Layers of the Alimentary canal © Goran tek-en is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Unit 10 figure 3 Gut Brain Axis © Kanmani Suganya & Byung-Soo Koo is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license