This Book’s Approach

This book’s approach is premised on a simple assumption: because behavioral economics is foremost a “test-and-learn” field of scientific inquiry that evolves according to experimental outcomes and practical, policy-orientated applications of the knowledge garnered from these outcomes, so too should students test-and-learn. Studying and practicing behavioral economics should occur simultaneously, which, in turn, suggests a course taught more according to a practicum approach than in a traditionally styled lecture format. As such, the book’s information and lessons are presented in a succinct and precise format.

The goal of this textbook is to help students experience behavioral economics through actual participation in the same experiments and economic games that have served as the foundations for, and shaped the contours of, the field. With the help of this book, students have the opportunity to learn behavioral economics firsthand and, in the process, create their own data and experiences. They will learn about themselves—about how they make private and public choices under experimental conditions—at the same time as they learn about the field of behavioral economics itself. They will be both the subjects and students of behavioral economics. What better way to learn?

Homo economicus vs. Homo sapiens

For ease of reference and exposition, we henceforth refer to the type of individual construed by the traditional rational-choice model as Homo economicus, a peculiar subspecies of human beings that is unfailingly omniscient, dispassionate, and self-interested when it comes to making choices. Homo sapiens, on the other hand, represents the rest of us—the often-flawed reasoners and sometimes-altruistic competitors who are prone to making decisions based primarily on emotion and heuristics.[1],[2]

The Textbook’s Different Sections

The textbook consists of four sections that, taken together, portray in full the eclectic methodologies comprising the field of behavioral economics. Sections 1 and 2 present the thought and actual laboratory experiments that have formed key pillars of the field, such as those experiments depicted in Examples 1 and 2 in the book’s Introduction section. The thought experiments in Section 1 are, for the most part, re-castings of the simple cognitive tests devised by psychologists and economists over the past three-to-four decades to illustrate the fallacies, miscalculations, and biases distinguishing Homo sapiens from Homo economicus. Similarly, the laboratory experiments presented in Section 2 are, for the most part, re-castings of the seminal experiments conducted by Kahneman and Tversky (among many others). These experiments helped motivate the revised theories of human choice behavior, such as Kahneman and Tversky’s (1979) Prospect Theory, which form another pillar of behavioral economics. Alongside these experiments, Section 2 presents the revised theories of human choice behavior with varying degrees of rigor. This is where the theoretical bases of Homo economicus’ rational choice behavior are examined, and where key refinements to this theory are developed—theoretical refinements underpinning the myriad departures from rational choice behavior we witness Homo sapiens make in this section’s laboratory and field experiments (and which are examined further in Sections 3 and 4).

Section 3 submerses the student in the world of behavioral game theory. Here we explore games such as Ultimatum Bargaining presented in Example 5. We follow Camerer (2003)’s lead, first by characterizing the games analytically (i.e., identifying solution, or equilibrium, concepts that are predicted to result when members of Homo economicus play the games), and then by discussing empirical results obtained from corresponding field experiments conducted with Homo sapiens. It is within the context of these games and field experiments that theories of social interaction are tested concerning inter alia trust and trustworthiness, honesty, fairness, reciprocity, etc. As with the thought and laboratory experiments presented in Sections 1 and 2, the games and field experiments presented in Section 3 are meant to be replicated with students as subjects and the instructor as the experimenter, or researcher.

Finally, Section 4 wades into the vast sea of empirical research and choice architecture. Here the student explores studies reporting on (1) the outcomes of actual policy nudges, such as the SMarT retirement-savings plan presented in Example 3 of the Introduction, (2) analyses of secondary datasets to test for choice behavior consistent with the revised theories discussed in Section 2, such as the test for loss aversion in Example 4 of the Introduction, and (3) analyses of primary datasets obtained from novel field experiments to further test the revised theories. The main purpose of this section is not only to introduce the student to interesting empirical studies and policy adaptations in the field of behavioral economics, but also, in the process, to incubate in the student an abiding appreciation for the obscure settings that sometimes lend themselves to such study.[3]

The Textbook’s Different Levels of Rigor

Because the mathematical and computational rigor of material presented in this textbook varies throughout, particularly in Sections 2 – 4, the extent of the rigor used in the presentation of a given topic is indicated with superscripts. Topics without a superscript are considered basic and universal enough that backgrounds in economics, mathematics, or statistics are not required for the reader to understand the material. Topics with a single asterisk (*) indicate that higher mathematical reasoning skills are recommended for the reader to fully grasp the material. Topics with a double asterisk (**) indicate that either higher economic or statistical reasoning skills, whichever the case may be, are recommended. And lastly, topics with the dreaded triple asterisk (***) indicate that both higher economic/statistical and mathematical computational skills are likely required to fully grasp the material. Both students and instructors should bear these indicators in mind.

For example, none of the topics presented in Section 1 are superscripted, implying that students from varied academic backgrounds should be able to fully understand the material presented. Single asterisks (*) first appear in Section 2, Chapter 3, indicating that the discussions of the Principle and Additional Rationality Axioms pertaining to Homo economicus will likely be more easily comprehended by students with higher mathematical reasoning skills. The double asterisk appears later in the same chapter when the topic of Homo economicus and the expected utility form is presented, and the bug-a-boo triple asterisk first appears at the end of Chapter 3, demarcating the topic of intertemporal choice.

Thinking Diagrammatically

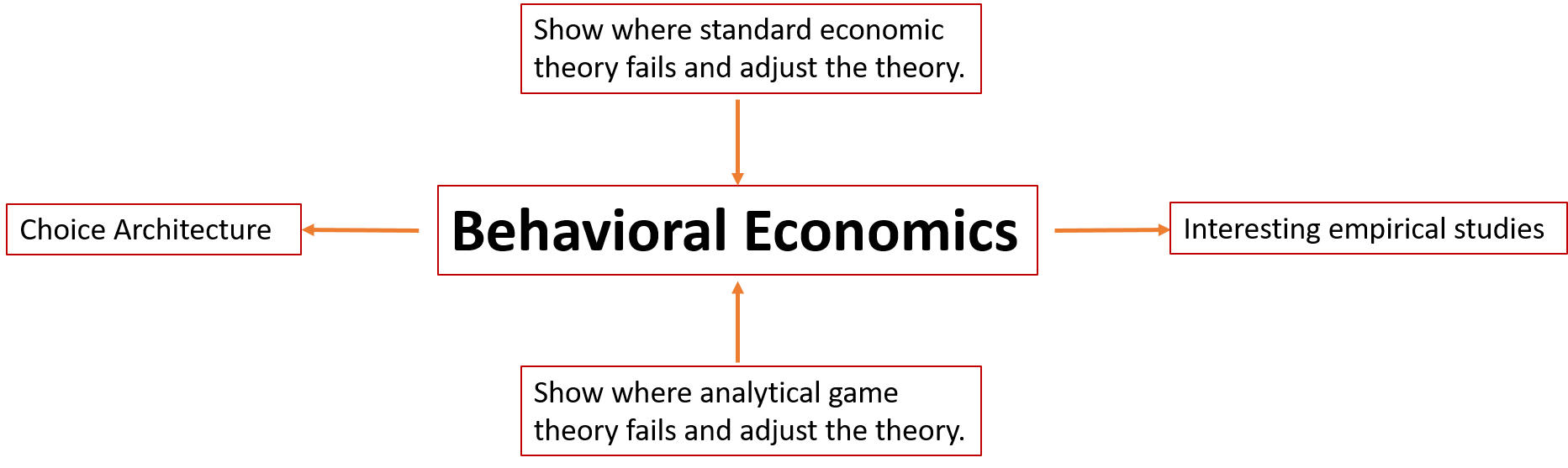

For those who prefer thinking diagrammatically, the figure below illustrates how these four sections relate to, and help define, what we thus far understand to be the field of behavioral economics.

The two boxes with arrows pointing inward toward Behavioral Economics can be thought of as the “inputs” to our understanding of the field. The box enclosing the statement, “Show where standard economic theory fails….” represents Section 1 of the guidebook, and “….adjust the theory” pertains to Section 2. The box enclosing the statement, “Show where analytical game theory fails and adjust the theory” represents Section 3. In contrast, the two boxes with arrows pointing outward from Behavioral Economics can be thought of as “outputs” in the sense of Choice Architecture (e.g., the SMarT retirement-savings plan described in Example 3 of the Introduction) and “interesting empirical studies” (e.g., the PGA study described in Example 4 of the Introduction). These two areas of interest are explored in Section 4.

The Textbook’s Appendices

Appendix A at the end of the book includes example Response Cards for the experiments and games presented in Sections 1-3. I am old-fashioned when it comes to collecting student responses—I print out a response card for each student for each experiment or game, have the students fill in their responses, and then pass around a “collection box” for each student to place his or her card in.

Student ID numbers on the response cards could be their names or their university ID numbers. Or, if you wish to align the students’ responses with more demographic information obtained from a survey instrument administered on the first day of class, you might consider randomly assigning the students individual course identification (CID) numbers on the first day of class. The CID numbers would not be tied to the students’ names or their university identification numbers. In this case, in order to preserve their anonymity, you would be precluded from basing the students’ course grades upon their performance in the experiments or their responses to the survey instrument. Appendix B includes a copy of a socio-demographic survey that could be administered to students the first day of class, after having randomly assigned their CID numbers. This information would be useful when it comes to analyzing the data obtained from the experiments and games. Again, because the surveys are linked to CID numbers rather than student names or university identification numbers, student anonymity regarding the survey instrument is ensured.

Appendix C includes examples of presentation slides used for lectures and as guides for the experiments and games as students proceed to participate in them. Appendix D includes examples of course outlines designed for courses targeting economics and non-economics majors, respectively. And a Linkages Matrix is provided in Appendix E. This matrix provides a structure for identifying connections between the various concepts presented in Chapters 1 – 4 and the experiments, games, and empirical studies discussed in Chapter 6 and later in Section 4.

Media Attributions

- Figure 5 (Introduction) © Arthur Caplan is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Homo economicus is Latin for “economic man.” Persky (1995) traces its use back to the late 1800s when it was used by critics of John Stuart Mill’s work on political economy. In contrast (and, as we will see, with no small touch of irony) Homo sapiens is Latin for “wise man.” For a deep dive into evolution of Homo sapiens, particularly from the start of the Cognitive Revolution 70,000 years ago, see Harari (2015). ↵

- We have all heard the saying that “words matter.” The titles and descriptions we use to distinguish people and their behaviors (e.g., Homo economicus vs. Homo sapiens) can reinforce or diminish behaviors such as pride in cultural heritage, respect for the living world, and trust in community, a process known as “crowding out” of “intrinsic motivation and commitment.” As an example of this phenomenon, Bauer et al. (2012) asked participants in an online survey to imagine themselves as one of four households facing a water shortage due to a drought affecting their shared well. The survey assigned the label “consumers” to half of the participants and “individuals” to the other half. Those imagining themselves as consumers reported feeling less personal responsibility to reduce their water demand, and less trust in others to do the same, than did those referred to as individuals. As we are about to learn, behavioral economics is all about exposing these types of “framing effects” existing in the “real world” inhabited by Homo sapiens. ↵

- Our approach to studying behavioral economics is focused on the underlying laboratory experimentation and behavioral games that form the bedrock of the field. As such, we eschew delving into related fields such as neuroeconomics and auction theory. See Cartwright (2018) and Just (2013) for introductions to the former and latter fields, respectively. ↵