1 Miscalculations, Cognitive Illusions, Misjudgments, and ‘Effects’

We begin by considering some well-known miscalculations that bedevil and typify Homo sapiens.

(Relatively Simple) Miscalculations

Answers

Box 1 — The ball costs $0.05.

Box 2 — It would take 5 minutes.

Box 3 — The syllogism is not valid.

Box 4 — It would take 47 days.

Homo economicus would have scored a perfect four out of four. What was your score?

(Relatively Complex) Miscalculation

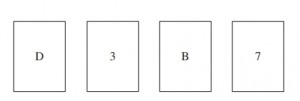

Wason (1968) proposed the following test of formal operational thought. Suppose you are shown four cards with the faces showing respectively “D,” “3,” “B,” and “7,” as displayed in the figure below.

You are told that a card with a number on one side (e.g., 3 or 7) has a letter on the reverse side (e.g., D or B). You are then asked which of the cards you would need to flip over to test the hypothesis that “If there is a D on one side of any card, then there is a 3 on its other side.”

Answer

To test this hypothesis, you would need to flip the D card. However, you would also need to flip over the 7 card as well. If the letter on the opposite side of the 7 card is D, then the hypothesis would be false.

Cognitive Illusions

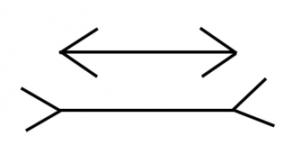

Ready to be weirded out? Which of the two horizontal lines is the longest?

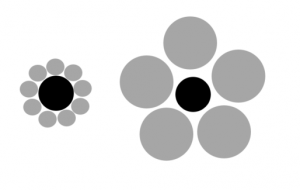

Are the sides of this cube bent inward?

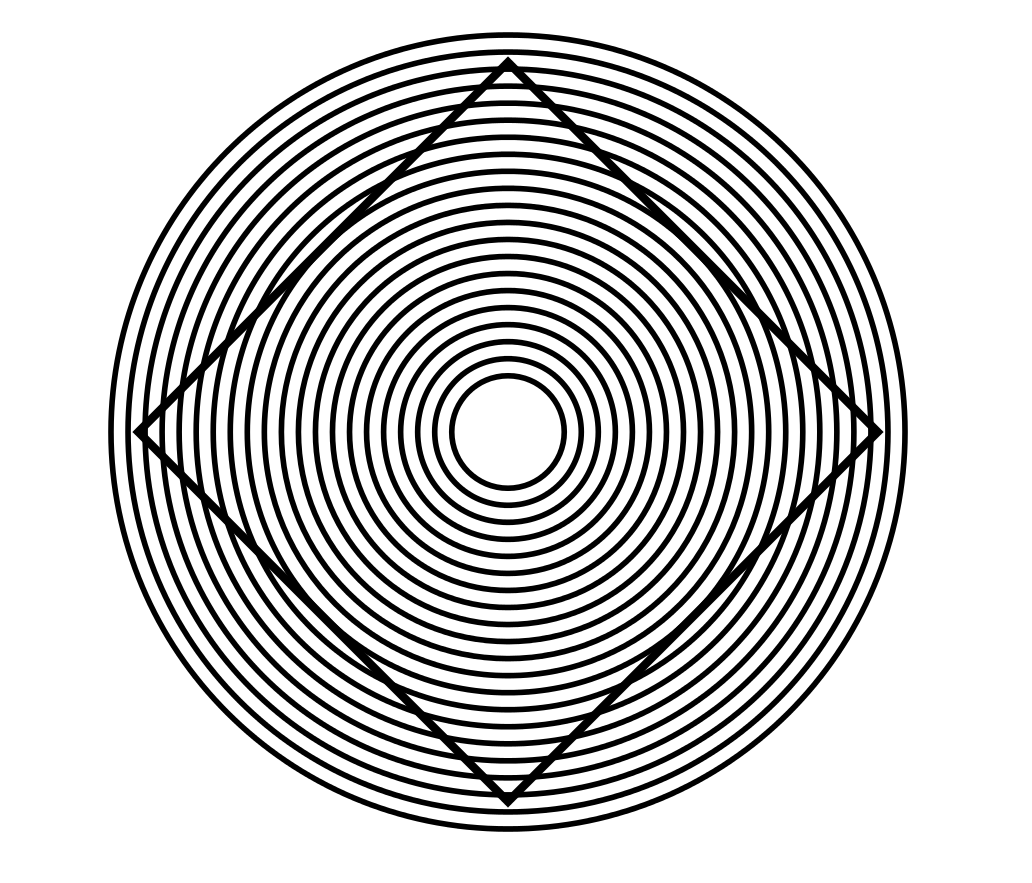

Which of the black circles is the largest?

Do you see a rabbit or a duck in this drawing?

Answers

1. Take a close look. The two lines are identical in length.

2. The sides of the cube are not bent inward.

3. Neither. The black circles are identical in size.

4. You can see both a rabbit and a duck in the drawing.

Homo economicus would provide correct answers to each question, no problem. How did you do? Biederman (1972) and Palmer (1975) contend that our visual perceptions are affected by both our prior conceptual structures and the characteristics of the visual stimulus itself. This would explain why you may have struggled to answer some of questions correctly.

Heuristics

A heuristic is a practical, problem-solving method that is not guaranteed to lead to an optimal or rational solution but is nonetheless deemed sufficient by an individual or organization for obtaining a short-term goal or approximation (Myers, 2010). Heuristics can lead Homo sapiens to misjudge situations that more reasoned thought or research would otherwise improve upon.[1]

Affect Heuristic

Have you ever based a decision upon your like or dislike of the object in question rather than on more objective information and logical reasoning? For example, maybe you’ve based your decision of whether to purchase stock in a company based upon your like or dislike of the company rather than whether the company’s stock price is under- or over-valued? If you have ever made a decision like this, then as Kahneman (2011) instructs us, you are guilty of an Affect Heuristic. The key to distinguishing this heuristic is the absence of any information or evidence that might otherwise be used to render judgment or make a decision. We might, therefore, call this the ignorance-is-bliss heuristic.

Availability Heuristic

Have you ever judged the frequency of an occurrence by the ease with which instances of the occurrence have come to your mind or you have personally experienced it? For example, a judicial error that affected you personally has undermined your faith in the justice system more than a similar incident that you read about in the newspaper? If you have ever judged an occurrence like this, then you were guilty of using an Availability Heuristic.

In an interesting study of the Availability Heuristic, Lichtenstein et al. (1978) asked subjects participating in an experiment whether they knew the likely causes of death in the US. The subjects were told that, on average, 50,000 people die each year due to motor vehicle accidents. They were then asked to state how many people they thought died from 40 other possible causes, ranging from venomous bites or stings, to tornados and lightning strikes, to floods, to electrocution, to fire and flames . . . I think you get the grim picture. The authors found that subjects tended to overestimate the number of people who die from less likely causes and underestimate the number of deaths from more likely causes. For example, the average number of deaths due to fireworks (a less likely cause) was estimated by the experiment’s subjects to be over 330 per year when the actual number is only six. And, the number of deaths due to electrocution (a more likely cause) was estimated by the subjects to be roughly 590 versus the actual number of over 1,000.

Subjects also tended to believe that two different causes associated with a similar number of deaths were instead associated with markedly different numbers of deaths. For example, homicides and accidental falls account for roughly 18,900 and 17,450 deaths per year, respectively, while, on average, the subjects believed these two death tallies to be roughly 8,440 and 2,600. While the actual ratio of deaths by homicide to deaths by accidental falls is only 1.08 (18,900 ÷ 17,450), the corresponding believed ratio is 3.25 (8,440 ÷ 2,600). Upon further questioning of the subjects, Lichtenstein et al. discovered that this upward bias correlated with newspaper coverage and whether a subject had direct experience with someone who had died from a given cause—the very things that influence an Availability Heuristic.

Needless to say, Homo economicus would never deign to use such heuristics. She would be fully informed of the actual death statistics.

Effects

Depletion Effect

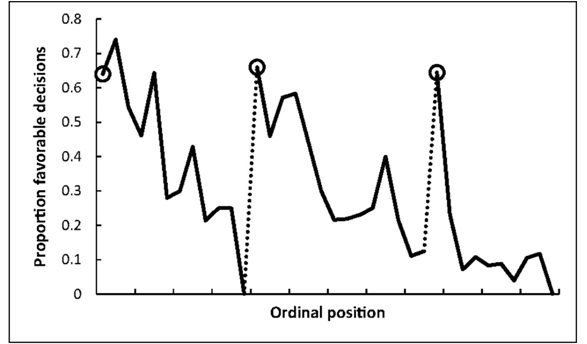

Danziger et al. (2011) studied the proportion of rulings made by parole judges in favor of prisoners’ requests for parole. Their results are depicted in the figure below.

Circled points in the figure indicate the proportions of first decisions made in favor of parole in each of three decision sessions. The first decision session began after morning break time. The second session began after lunch break, and the third session began after afternoon break time. Tick marks on the horizontal axis denote every third case heard by the judges, respectively, and the dotted lines indicate food breaks.

Note that for each decision session, the rulings begin in favor of parole and then steadily decline as the end of each session is approached. Apparently, the judges get crankier as each session wears on. Their sympathies suffer what’s known as a Depletion Effect.

We would expect no such pattern from Ludex economicus (judges from the Homo economicus species). But what exactly would that pattern be?

Priming Effect

Consider these two thought experiments.

Last night Sally and Bob went out to dinner together. They enjoyed a meal at Wai Wai’s Noodle Palace

S O _ P

Last night Thida came home from work feeling tired and sweaty from a long day of work. She took a long shower.

S O _ P

If you chose the letter “u” for the first box and “a” for the second box, then you are likely guilty of what Kahneman (2011) calls a Priming Effect. As these experiments demonstrate, priming Homo sapiens is rather easy.

Priming Effect (Version 2)

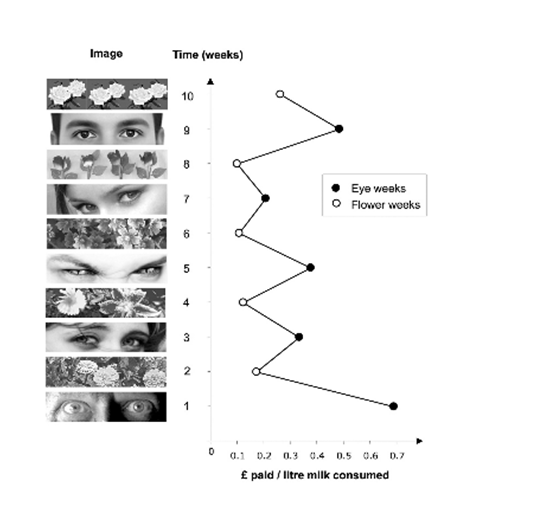

Bateson et al. (2006) examined the effect of an image of a pair of eyes on contributions made by colleagues to an “honesty box” used to collect money for drinks in a university coffee room. Suggested prices for the drinks were listed as follows (“p” stands for British “pence”).

Coffee (with or without milk): 50p

Tea (with or without milk): 30p

Milk only (in your coffee or tea): 10p

Full cup of milk: 30p

Please put your money in the blue tin.

Thanks, Melissa.

The figure below presents the study’s results.

Relative to the week before, when a photo of a floral arrangement was shown, the week associated with human eyes staring back at Melissa’s colleagues resulted in more money contributed to the honesty box. All told, the authors report that their colleagues contributed nearly three times as much for their drinks when a pair of eyes were displayed rather than the floral arrangement. This result suggests the importance of the social cue of being watched (and thus, reputational concerns) on cooperative behavior among humans. It is another example of a Priming Effect.

Homo economicus would not have been swayed by such cues and reputational concerns. Instead, he would have exhibited what’s known as free-riding behavior, never or only rarely contributing to the honesty box, irrespective of whether a pair of eyes were glaring or flowers blooming.

Priming Effects Abound

Examples of the Priming Effect abound. For example, Kahneman (2011) mentions research suggesting that “money-primed” people demonstrate more individualism (i.e., more independent-minded and selfish behaviors and a stronger preference for being alone). Berger et al. (2008) find that support for ballot propositions to increase funding for public schools is significantly greater when the polling station is located in a school rather than a nearby location.

Can you identify ways in which you are primed in your daily life? Of course, Homo economicus would be compelled to answer “no” to this question.

Mere Exposure Effect

Zajonc and Rajecki (1969) ran an interesting field experiment on the campuses of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University. For a period of 25 days, an ad-like box appeared on the front pages of the student newspapers containing one of the following Turkish words: KADIRGA, SARICIK, BIWONJNI, NANSOMA, IKTITAF. The frequency with which the words were repeated varied. One of the words was shown only once, and the others appeared on two, five, ten, or twenty-five separate occasions. No explanations were offered to the readers of the papers. When the mysterious ads ended, the investigators sent questionnaires to readers asking for their impressions of whether each of the words “means something good or something bad.” The words presented more frequently were rated much more favorably than the words shown only once or twice. This has come to be known as the Mere Exposure Effect.

Intentional Causation

Consider the following thought experiment.

Read this sentence:

After spending a day exploring beautiful sights in the crowded streets of New York City, Jane discovered that her wallet was missing.

What comes to mind? Any chance that Jane was pickpocketed? If so, then you have succumbed to what Kahneman (2011) calls Intentional Causation.

Jumping to Conclusions

The website Effectiviology provides several examples of how we Homo sapiens jump to conclusions (https://effectiviology.com/jumping-to-conclusions/). Have you ever made ‘jumps’ like these?

- Immediately deciding that a restaurant’s food is bad because its windows are smudged.

- Believing someone is rich because she drives a fancy car.

- Believing you will fail a test because you struggled with some of the practice questions.

- Thinking someone does not like you because they were not enthusiastic when you said “good morning”.

- Thinking a house is on fire because you see smoke coming out of a window.

- Assuming that because you did not get along with one person from a certain social group, you will not get along with anyone else from that group either.

If so, then join the proverbial club. Jumping to conclusions is an easy thing to do.

Framing Effect

Consider the following thought experiment.

Different ways of presenting the same information evoke different interpretations. Consider two car owners who seek to reduce their costs:

Sylvester switches from a gas-guzzler of 5 miles per gallon (mpg) to a slightly less voracious guzzler that runs at 6 mpg. The environmentally virtuous Elizabeth switches from a 13 mpg car to one that runs at 17 mpg. Both Sylvester and Elizabeth drive their cars 16,000 miles per year. Who will save more gas by switching?

If you chose Elizabeth you have fallen victim to what is known as a Framing Effect. Guess again.

Elizabeth saves (16,000÷13) − (16,000÷17) = 1,231 − 941 = 290 gallons per year, while Sylvester saves (16,000÷5) – (16,000÷6) = 3,200 – 2,667 = 533 gallons per year!

Halo Effect

Consider the following thought experiment.

Who do you think has more virtuous qualities, Abigal or Anne?

Abigal: intelligent, industrious, impulsive, critical, stubborn, envious

Anne: envious, stubborn, critical, impulsive, industrious, intelligent

Note that Abigal and Anne share the same qualities. The only difference is that the more virtuous qualities are listed first for Abigal and last for Anne. As a result, you are more likely to choose Abigal as having the more virtuous qualities simply because of a type of Framing Effect called the Halo Effect. Surely, Homo economicus would have identified Abigal and Anne as equally virtuous individuals.

In one of the earliest laboratory experiments designed to measure the Halo Effect, Nisbett and Wilson (1977) had a group of students observe videotaped interviews with a professor who spoke with a pronounced foreign accent and then rate his “likeability.”[2] As the authors point out, when we like a person, we often assume that those attributes of the person about which we know relatively little are also favorable. For example, a person’s appearance may be perceived as more attractive if we like the person than if we do not.

The subjects in Nisbett and Wilson’s experiment (roughly 120 University of Michigan students enrolled in an introductory psychology course) were told that the investigators were studying the possibility that ratings of an instructor presented in such a brief fashion might resemble ratings by students who had taken an entire course with the instructor. The subjects were shown one of two different seven-minute, videotaped interviews with the same instructor, a native French-speaking Belgian who spoke English with a fairly pronounced accent. In one interview, the instructor presented himself as a likable person, respectful of his students’ intelligence and motives, flexible in his approach to teaching, and enthusiastic about his subject matter (i.e., he portrayed himself as a “warm teacher”). In the other interview, the instructor appeared to be quite unlikable, cold and distrustful toward his students, rigid and doctrinaire in his teaching style (i.e., portraying a “cold teacher”). After viewing the videotaped interview, the subjects rated the instructor’s likability, as well as the attractiveness of his physical appearance, his mannerisms, and his accent. It was anticipated that the subjects would rate the instructor as having a more attractive physical appearance, more attractive mannerisms, and a more attractive accent when he was likable than when he was unlikable.

A substantial majority of the subjects who observed the interview with the warm teacher rated his physical appearance as appealing, whereas a substantial majority of those who observed the interview with the cold teacher rated his appearance as irritating. Similarly, a majority of subjects viewing the warm teacher rated his mannerisms as appealing, whereas a majority of subjects viewing the cold teacher rated his mannerisms as irritating. Lastly, about half of the subjects viewing the warm teacher rated his accent as appealing, while half rated the accent as irritating, whereas the overwhelming majority of subjects who viewed the cold teacher rated his accent as irritating.[3]

Hence, it appears that unlike Homo economicus, who would not be swayed by inconclusive evidence such as a seven-minute interview, Homo sapiens can indeed be influenced by these types of first encounters and attendant impressions. We tend to fall prey to the Halo Effect.

Ordering Effect

Hogarth and Einhorn (1992) investigate what’s known as the Ordering Effect, which is associated with how Homo sapiens update their beliefs over time—for example, how first impressions of an acquaintance are updated as you spend more time together.[4] The authors consider three pertinent questions concerning this updating process. First, under what conditions does information processed earliest in the updating sequence have greater influence (i.e., produce a Primacy Effect)? Second, under what conditions is later information more important (i.e., produce a Recency Effect)? And third, under what conditions is order irrelevant? In general, Hogarth and Einhorn consider order effects of the following type:

There are two pieces of evidence, A and B. Some subjects express an opinion after seeing the information in the order A-B; others receive the information in the order B-A. An order effect occurs when opinions formed after A-B differ from those formed after B-A.

To test for Primacy and Recency Effects, the authors present subjects in their experiments with a set of four scenarios, each of which involves an initial description (the stem) and two additional pieces of information presented in separate paragraphs (the evidence). The content of the four stems consists of the following: (1) a defective stereo speaker thought to have a bad connection; (2) a baseball player named Sandy whose hitting has improved dramatically after a new coaching program; (3) an increase in sales of a supermarket product following an advertising campaign; and (4) the contracting of lung cancer by a worker in a chemical factory. Note that each stem consists of an outcome (e.g., Sandy’s hitting has improved dramatically), and a suspected causal factor (e.g., a new coaching program). After reading a stem, subjects are asked to rate how likely the suspected causal factor was the cause of the outcome on a rating scale from 0 to 100. For example, in the baseball scenario, subjects are asked, “How likely do you think that the new training program caused the improvement in Sandy’s performance?”

In one experiment (Experiment 1), subjects are provided with both “strong” and “weak” positive evidence to nudge them toward a revised answer. Continuing with the baseball scenario, the positive evidence consists of two sentences: “The other players on Sandy’s team did not show an unusual increase in their batting average over the last five weeks. In fact, the team’s overall batting average for these five weeks was about the same as the average for the season thus far.” The first sentence provides strong positive evidence and the second sentence provides weak positive evidence. Thus, the evidence is provided in a “strong-weak order” (strong-weak and weak-strong orderings were randomized across subjects). After reading the evidence, subjects are asked again to rate how likely the suspected causal factor was the cause of the outcome on a rating scale from 0 to 100.

In Experiments 2 and 3, the same procedures were followed except that in Experiment 2 the two pieces of evidence consist of strong negative and weak negative information about the outcome, and in Experiment 3 the two pieces of information are mixed, involving positive and negative information. An example of negative information in the baseball scenario is, “The games in which Sandy showed his improvement were played against the last place team in the league. Pitchers on that team are very weak and usually allow many hits and runs.”

Hogarth and Einhorn’s hypotheses were that subjects participating in Experiments 1 and 2 should not exhibit an Ordering Effect since the evidence was either purely positive or purely negative—the ordering of strong vs. weak should, therefore, not measurably impact a subject’s initial rating of the likelihood of the suspected causal factor having caused the outcome. However, the ordering of the mixed evidence in Experiment 3—positive-negative vs. negative-positive—should impact a subject’s initial rating.

Each of the authors’ hypotheses was confirmed by the experiments. In Experiment 3 they found statistically significant evidence of a Recency Effect.[5] Specifically, the positive-negative order resulted in an average decrease in the subjects’ ratings of slightly more than 9, relative to the average initial judgment, and the negative-positive order resulted in an average rating increase of slightly less than 3. Recency in this case is tied to the evidence provided in the second sentence as opposed to the first sentence. Had the result been reversed (i.e., it was the first sentence that drove the average change in rating rather than the second sentence), then Hogarth and Einhorn would have instead found evidence of a Primacy Effect.

Of course, we would expect neither recency nor primacy to affect Homo economicus.

Anchoring Effect

Kahneman (2011) describes another effect known as the Anchoring Effect, whereby a subject’s answer to a question is anchored to information that is contained in the question itself. For example, suppose Individual 1 is presented with Question 1 below, and Individual 2 is presented with Question 2. Assume that both individuals are so alike we can almost think of them as clones of one another. Neither of them actually knows how old Gandhi was at death.

1. Was Gandhi younger or older than 114 years at his death? How old was Gandhi at his death?

2. Was Gandhi younger or older than 35 years at his death? How old was Gandhi at his death?

If the two individuals each suffer from the Anchoring Effect, then Individual 1 will answer a higher age than Individual 2. This is because Individual 1’s anchor age in his or her question, 114 years, is so much higher than Individual 2’s anchor of 35 years. Based on their disparate answers, an Anchoring Index can be calculated as (Individual 1’s answer – Individual 2’s answer) ÷ (114 – 35).

Of course, if the two individuals happen to be from the species Homo economicus, they would both answer 78 years old, which was Gandhi’s actual age at death. And in this case, their Anchoring Index would equal zero!

In a classic test of the anchoring effect among Homo sapiens, Ariely et al. (2003) asked students in a laboratory experiment whether they would be willing to purchase a box of Belgian Chocolates for more money than the last two digits of their Social Security Numbers (SSNs). For example, if the last two digits of a participant’s SSN were 25, then s/he was asked whether s/he would be willing to pay (WTP) more than $25 for the chocolates. The participants were then asked for the specific amount they would be WTP. Because SSNs are assigned randomly, the authors hypothesized that there should be no relationship between the participants’ SSNs and their respective WTP values. On the contrary, Ariely et al. (2003) found a positive relationship between the participants’ SSNs and WTP values, suggesting that a Homo sapiens’ SSN can induce an Anchoring Effect, particularly when it comes to our WTP values for Belgian Chocolates. Yum!

In a separate experiment, Ariely et al. sought to answer the attendant question, do Homo sapiens flip-flop from one anchor price to another, continually changing our WTP values? Or does the first anchor price we encounter serve as our anchor over time and across multiple decisions (i.e., do we exhibit what the authors call coherent arbitrariness)? For their experiment, the authors recruited approximately 130 students attending a job recruitment fair on the MIT campus. The experiment subjected each participant to three different sounds through a pair of headphones. Following each sound, the participants were asked if they would be willing to accept a particular amount of money (which served as the experiment’s anchor price) for having to listen to the sounds again. One sound was a 30-second, high-pitched, 3,000-hertz sound, mimicking someone screaming in a high-pitched voice (Sound 1). Another was a 30-second, full-spectrum (white) noise, similar to the noise a television set or radio makes when there is no reception (Sound 2). The third was a 30-second oscillation between high-pitched and low-pitched sounds (Sound 3). Ariely et al. used these particular sounds due to there being no existing market for annoying sounds (therefore, the participants were precluded from confounding their responses in the experiment with a pre-existing market price).

For the first part of the experiment, anchor prices of 10 cents or 90 cents were randomly assigned to the participants. After indicating whether they would accept their anchor price for listening to Sound 1 again (“yes” or “no”), each participant then indicated the lowest price they would willingly accept to listen to the sound again. Participants whose price was lowest “won” the opportunity to hear Sound 1 again, and actually got paid for doing so. The remaining participants were not given the opportunity to listen to the sound again (and thus, were not paid for this part of the experiment). As expected, the authors found that those participants whose anchor price was 10 cents stated a lower willingness to listen value to Sound 1 again (33 cents on average) relative to those whose anchor price had been 90 cents (73 cents on average).

To test how influential the anchor prices of 10 cents and 90 cents were in determining future decisions, Ariely et al. then subjected each participant (from both the 10-cent and 90-cent anchor price groups) to Sound 2 and asked if they would be willing to accept a payment of 50 cents to endure the sound again. Similar to the first part of the experiment, after indicating whether they would accept 50 cents for listening to Sound 2 again, each participant stated the lowest price they would willingly accept to listen to the sound again. It turned out that the original 10-cent group stated much lower prices than the original 90-cent group. Although both groups had subsequently been exposed to the 50-cent anchor price, their original anchor prices (10 cents for some, 90 cents for others) predominated. In other words, Homo sapiens exhibit persistent Anchoring Effects.

In the experiment’s final stage, participants were instructed to listen to Sound 3. This time, Ariely et al. asked each of the original 10-cent group members if they would be willing to listen to this sound again for 90 cents. And Ariely et al. asked each of the original 90-cent group members if they would be willing to listen to this sound again for 10 cents. Having flipped the anchor prices, the authors could now discern which anchor price—the first or the second—exerted the greatest influence on the participants’ stated prices. Once again, each participant was then asked how much money it would take to willingly listen to Sound 3 again.

The final results were that (1) those participants who had first encountered the 10-cent anchor price stated relatively low prices to endure Sound 3 again, even after 90 cents was stated as the subsequent anchor price, and (2) those who had first encountered the 90-cent anchor price demanded relatively high prices, even after 10 cents was stated as the subsequent anchor price. Therefore, Ariely et al. conclude that our initial decisions anchor future decisions over time. Or, to put it another way, first impressions are important. Anchoring Effects remain with us long after an initial decision is made. This is what explains, for example, the heuristic of brand loyalty. As Ariely (2008) points out, loyal Starbucks customers likely share the same story explaining their fealty. Following their first experience drinking a Starbucks coffee, they apply the following heuristic: “I went to Starbucks before, and I enjoyed both the coffee and the overall experience, so this must be a good decision for me.” And so on. This can also explain how you might start with a small drip coffee (your anchor) and subsequently work your way up to a large Frappuccino.[6]

Silo Effect

A Silo Effect occurs when a system is not in place that enables separate departments or teams within an organization to communicate effectively with each other. Productivity and collaboration suffer as a result. A classic example of the Silo Effect is when two departments within a given organization are working on practically identical initiatives or projects but neither department is aware of what the other is doing (Marchese, 2016). This phenomenon is also known as homophily (i.e., when contact occurs more often between similar than dissimilar departments).

Although conventional wisdom has suggested for some time now that breaking down silos and fostering interorganizational partnerships to achieve public health outcomes has distinct advantages, and examples can indeed be found where the practice of collaboration is growing within the public health system, Bevc et al. (2015) set out to measure the extent to which disciplinary and organizational silos that have traditionally characterized public health still exist. In particular, the authors test for the persistence of Silo Effects in over 160 public health collaboratives (PHCs); social networks comprised of diverse types of partners (e.g., including law enforcement agencies, nonprofit advocacy groups, hospitals, etc.); varying levels of interaction; and multiple configurations designed to increase common knowledge and resource sharing. Interestingly, Bevc et al. find that as network size increases, a potential bias is observed among specific organization types in terms of their choosing to interact with similar organizations (e.g., for law enforcement agencies to collaborate with other law enforcement agencies, nonprofits with other nonprofits, and public health organizations with other public health organizations, etc).

Thus, even in settings where reducing the impulse for homophily is explicitly being targeted, Homo sapiens persist in occupying their silos. Given their ubiquitous understanding of the benefits of collaboration among dissimilar groups, Homo economicus would never have built such silos in the first place.

Study Questions

-

- Describe two instances in your own life where you have adopted the Affect and Availability Heuristics to help you in making decisions. What drove you to adopt these heuristics? Do you believe the heuristics served you well? Why or why not?

- Browse the internet for a challenge question that, like those presented in this chapter, instigate miscalculation and error in reasoning. Also, find a cognitive illusion that elicits the same sense of wonderment as those presented in this chapter.

- Can you think of another sector of society besides the judiciary where the Depletion Effect has potentially profound implications? Explain.

- The Honesty Box described in Priming Effect (Version 2) is an example of a public good funded by voluntary contributions, and the human eye-floral arrangement prompts are pre-contribution mechanisms designed to induce full payment by coffee-room attendees. Can you think of a post-contribution mechanism that might also induce full payment to the Honesty Box? How would this mechanism actually work?

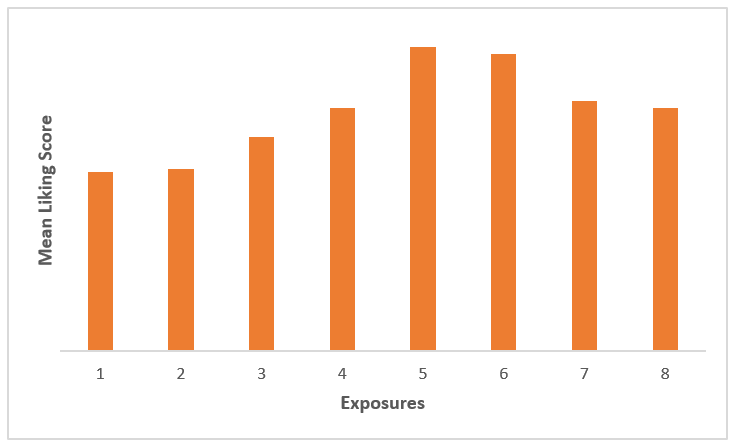

- Suppose you have conducted a field experiment with a group of 50 adults to measure the incidence of a Mere Exposure Effect. You have them listen to the new Bruce Springsteen song “Letter to You” once per day over a period of eight consecutive days, and then register their Liking Score (the extent to which they have enjoyed listening to the song) after each listen. You summarize your results in the bar graph below. Are these results evidence of a Mere Exposure Effect?

- Warning: This question concerns a politically charged event that occurred on January 18, 2019, at the Indigenous People’s March in Washington, D.C. After reading this account of what happened at the march, and viewing this video of the event, which of the effects presented in this chapter do you think best describes this episode in our nation’s history?

- Think of a situation in your own life when you framed information (either wittingly or unwittingly) in such a way that helped pre-determine an outcome. Describe the situation and how you framed the information. Was the outcome improved or worsened as a result of how you framed the information?

- After having learned about the Anchoring Effect in this chapter, do you think you will ever fall for something like this again?

- When someone admonishes you “not to judge a book by its cover,” or as British management journalist Robert Heller once noted, “Never ignore a gut feeling, but never believe that it’s enough,” what heuristic(s) is he unwittingly advising you to avoid using?

- Browse the internet for information about an effect that was not discussed in this chapter. Can you classify this effect as a special case of a Priming or Framing Effect? Explain.

- Browse the internet for a heuristic other than the Affect and Availability Heuristics described in this chapter. Explain the heuristic.

- It’s one thing to detect the existence of a Silo Effect and quite another to measure its negative impacts on relationships between organizations or individuals. Identify a setting or situation where a Silo Effect exists and design a field experiment to measure the impacts of this effect on an outcome of interest.

- The Halo Effect suggests that someone who is perceived as being physically attractive has an advantage in certain situations—for example, when applying for a job. Can you think of why the halo might have a reverse effect?

Media Attributions

- Figure 6 (Chapter 1) © Arthur Caplan is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 8 (Chapter 1) © Arthur Caplan is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 8a (Chapter 1) © David Eccles is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 8b (Chapter 1)

- Rabbit-Duck Illusion © Fastfission~commonswiki is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 12 (Chapter 1) © 2021 National Academy of Sciences is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Figure 12 (Chapter 1) © 2006 The Royal Society is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Figure 17 (Chapter 1) © Arthur Caplan is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- As we will learn in Section 4, heuristics can, in some cases, lead to preferable outcomes. ↵

- This was by no means the first such Halo-Effect experiment. For instance, an earlier experiment conducted by Landy and Sigall (1974) found that evaluations of an essay (written by an unknown author) made by male college students were graded substantially higher when the alleged author was an attractive woman rather than an unattractive woman. This Halo Effect was pronounced, especially when the essay was of relatively poor quality. ↵

- In Chapter 5 we will learn how researchers discern differences like these on a more formal, statistical basis. ↵

- Similar to how the Halo Effect represents a special case of a Framing Effect, you should recognize that the Ordering Effect is likewise a special case of a Framing Effect. ↵

- We explicitly define what we mean by “statistically significant” in Section 4. For now, think of statistically significant this way: the result of an experiment is statistically significant if it is likely not caused by chance for some given level of confidence, typically 95%. ↵

- Ariely goes on to explain what likely attracted you to Starbucks in the first place. ↵