9 The Studies and Experiments

Discrimination in the Weakest Link Game Show

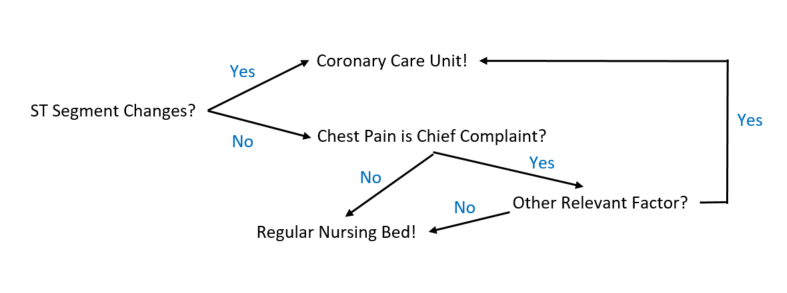

We begin with a study of potential discrimination exhibited by contestants in a popular British game show called the Weakest Link. This is not a show where contestants play the Weakest Link Game described in Chapter 8. Rather, the goal of the game is for a group of contestants to vote individuals off the show one-by-one in successive rounds until only two contestants remain to compete for a grand prize. The contestants who are voted off are considered “weak links” as a consequence of strategic play by the individual members of the group. Weak links are considered liabilities to the remaining group members in terms of building up the jackpot and, potentially, being one of the two remaining contestants to play for it. If you have the time and are interested in watching the show, check out this Youtube video (and hold onto your Bowler hat. It’s a lively, fast-paced contest).

Levitt (2004) observed that contestant voting behavior on the show provides an opportunity to distinguish between what he calls taste-based (bad!) and information-based (not as bad!) theories of discrimination. Taste-based discrimination occurs when an individual prefers not to interact with a particular class of people, and he is willing to pay a financial price to avoid such interactions. In contrast, an individual practicing information-based discrimination has no animus against a particular class of people but discriminates nonetheless because she has less reliable (i.e., noisy) information about them.

Contestants answer trivia questions over a series of rounds, and one contestant is eliminated each round based upon the votes of the other contestants until only two contestants remain. The last two contestants compete head-to-head for the winner-take-all prize. Because the prize money at stake is potentially large (the money is an increasing function of the number of questions answered correctly by the group over the course of the game’s rounds), contestants have powerful incentives to vote in a manner that maximizes their individual chance of being one of two remaining contestants to compete for the jackpot.

In the early rounds of the contest, strategic incentives encourage voting for the weakest competitors. However, in later rounds, the incentives reverse, and the strongest competitors become the logical target of eviction. Both theories of discrimination suggest that, in early rounds, excess votes will be cast against people targeted for discrimination. If group members practice taste-based discrimination, then in later rounds, these excess votes would persist, whereas if information-based discrimination is practiced, then votes against the targeted people would diminish.

Levitt (2004) found that contestants voted strategically in early rounds of the game but not in later rounds. Specifically, voting strategically means both voting off players who, in the game’s early rounds, more frequently answer questions incorrectly or “take a pass” on providing an answer (and thus do not contribute as much toward the ultimate jackpot by answering correctly), and voting off players in later rounds who consistently answered questions correctly in the previous rounds (since they now present more of a threat to make it to the game’s final round). There is little evidence to suggest that contestants discriminate against women, Hispanics, and people of African descent. However, some evidence suggests taste-based discrimination against older players.

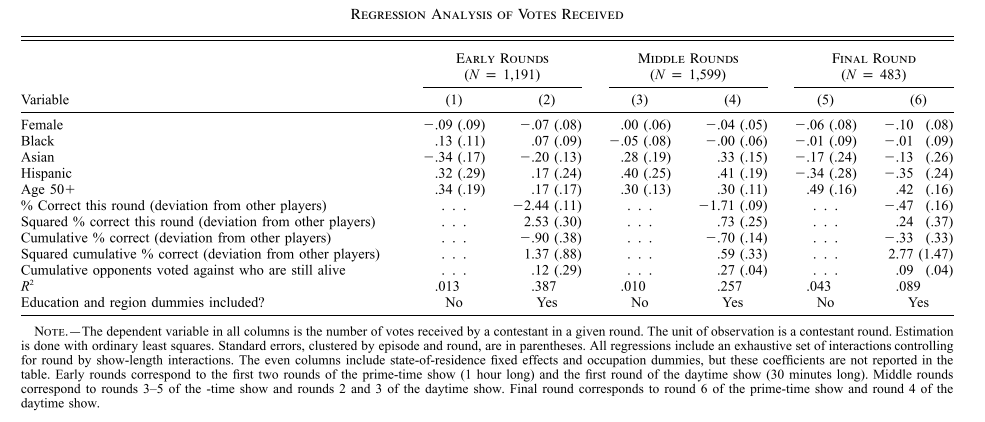

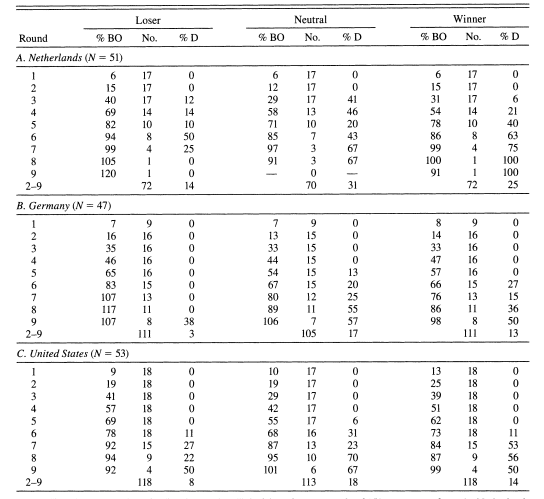

For those of you with a background in statistics or econometrics, Levitt’s (2004) specific results are presented in the table below:

In a proverbial nutshell, the numbers not in parentheses indicate the sign and size of a given variable’s effect on receiving votes (in favor of being removed from the group). The numbers in parentheses are called “standard errors” (SE). They are strictly positive numbers. Roughly speaking, the smaller an SE relative to the magnitude of its corresponding variable’s effect on votes received, the more “statistically significant” is the effect. For example, consider the effect of being female in the game’s early rounds. Although this effect is negative (-0.09), because the magnitude is very close (in this case exactly equal) to its corresponding SE of 0.09, we say that the ‘female effect’ is non-existent in a statistical sense.[1]

Taste-based discrimination is evident when an effect is positive and statistically significant in both the early and later rounds. Especially in the early rounds, votes should be based strictly on performance (i.e., a contestant’s ability to answer questions correctly on behalf of the group), not gender, ethnicity, or age. We see from column (1) that solely older contestants (age 50+) satisfy this condition (in column (1) the Age 50+ value of 0.34 is almost double the size of its corresponding SE of 0.19).[2] Results in columns (3) and (4) for Age 50+ suggest a positive Age 50+ effect in the middle rounds as well.

Lastly, results for the variable “% Correct this round” provide evidence of the previous claims that contestants vote strategically in the early rounds of the contest but not in the later rounds. The large negative (and statistically significant) effect in column (2) of -2.44 indicates that, all else equal, contestants cast fewer votes for fellow contestants who provide correct answers more often. In the middle and final rounds, this effect should become positive if contestants vote strategically. We see from columns (4) and (6) that this does not happen—large negative (and statistically significant) effects persist in these later rounds.

Discrimination in Peer-to-Peer Lending

Pope and Sydnor (2011) also test for discrimination in a novel context—peer-to-peer lending on the website Prosper.com. Peer-to-peer lending is an alternative credit market that aggregates small amounts of money provided by individual lenders to fund moderately sized, uncollateralized loans to individual borrowers. Like most standard credit applications, Prosper.com publicizes loan information from the prospective borrower’s credit profile. However, borrowers may also include optional personal information in their listing in the form of photographs and text descriptions. These pictures and descriptions can provide potential lenders with signals about characteristics such as race, age, and gender that anti-discrimination laws typically prevent traditional lending institutions from using.

Using data from 110,000 loan listings appearing on Prosper.com from 2006-2007, the authors find evidence of significant racial discrimination in this market. Loan listings that include a photograph of a Black borrower result in a 30% reduction in the likelihood of that loan receiving funding, all else equal. Further, a loan listing tied to a Black borrower results in an interest rate that is 60 basis points higher than an equivalent listing for a white borrower.[3] These results meet what the authors claim is a necessary condition for taste-based discrimination as defined by Levitt (2004). The question of whether the sufficient condition for this type of discrimination is met depends upon whether Black borrowers have statistically lower loan default rates and produce higher net returns for lenders. If the answer is “yes,” then together with the fact that they are less likely to receive funding and pay higher interest rates on loans they do receive, evidence of taste-based discrimination against Black borrowers is evinced.[4]

The authors find that Black borrowers are approximately 36% more likely to default on their loans than are Whites with similar characteristics, and a lender’s average net return from a loan to a Black borrower is eight percentage points lower over a three-year period. Thus, they conclude that discrimination in peer-to-peer lending could in fact be information- rather than taste-based.

What’s In a Name?

According to the Economic Policy Institute’s (EPI’s) recent assessment of the US labor market, Black workers are twice as likely to be unemployed as White workers overall (6.4% vs. 3.1% unemployment rates, respectively)—a gap that, while narrower, persists among workers Black versus White workers with college degrees (3.5% vs. 2.2%) (Williams and Wilson, 2019). Further, when employed, Black workers with college or advanced degrees are more likely than their White counterparts to be underemployed—roughly 40% of Black college graduates are in jobs that typically do not require a college degree, compared with only 31% of their White counterparts. The EPI concludes that persistence in relatively high Black unemployment and skills-based underemployment indicates that racial discrimination remains a failure of the US labor market, even when the market is tight.

The question naturally arises as to whether employers do in fact favor White applicants over similarly skilled Black applicants (i.e. do employers discriminate among job candidates based upon race?). Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004) provide an answer based upon an intriguing field experiment where fictitious resumes were sent by the authors in response to help-wanted ads in Boston and Chicago newspapers. To manipulate perceived race, the resumes were randomly assigned Black- or White-sounding names, such as Lakisha Washington or Jamal Jones (Black-sounding names) in response to half the ads, and Emily Walsh or Greg Baker (White-sounding names) in response to the other half.

Because they were also interested in how credentials affect the racial gap in interview callbacks, Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004) varied the quality of the resumes. Higher-quality applicants had on average more labor-market experience and fewer holes in their employment history. These applicants were also more likely to have an email address, have completed some certification degree, possess foreign language skills, or have been awarded some honors. The authors generally sent four resumes in response to each ad—two higher-quality and two lower-quality. They randomly assigned Black-sounding names to one of the higher- and one of the lower-quality resumes. In total, the authors responded to over 1,300 employment ads in the sales, administrative support, clerical, and customer services job categories, sending out nearly 5,000 resumes in total.

Overall, White names received 50% more callbacks for interviews, which Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004) translate into a White name being as valuable as an additional eight years of experience on a Black person’s resume. Callbacks were also more responsive to resume quality for White than for Black names. The racial gap in interview callbacks was uniform across occupation, industry, and employer size. The authors also found that living in a “better” neighborhood (wealthier or more-educated or Whiter) increased callback rates. However, Blacks were not helped more than Whites by living in better neighborhoods. As the authors point out, if ghettos and bad neighborhoods are particularly stigmatizing for Blacks, one might have expected Blacks to have been helped more by having a better address. These results do not support this hypothesis.

Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004) also find that, across all sent resumes, the difference in percent callbacks for White- versus Black-sounding names is a statistically significant 3.2%. Callback discrimination based upon race occurs against both men and women, and the discrimination against Black women occurs mostly in conjunction with administrative rather than sales jobs.[5]

It is humbling to think that Homo economicus employers, whose color-blindness is a patent feature of their rational minds, would not fall victim to racial discrimination in the hiring process. Thankfully, as the topic below, Awareness Reduces Racial Discrimination, suggests, when racial discrimination is brought to light its practice tends to dissipate.

Can Looks Deceive?

Similar to Prosper.com, but with a bit more (how shall we say?) gravity, online dating services create a natural setting within which to assess the impacts of a person’s physical appearance on a transaction between that person and a potential (how shall we say?) customer. One dating site, OkCupid, recently became interested in answering the simple question, to what extent do looks deceive? The site’s answer is based upon a natural experiment conducted with their users on what OkCupid named “Love is Blind Day,” January 15, 2013, celebrating the release of their new phone app. Comparing that day’s messaging data to the average day’s historically, Rudder (2014) uncovered several interesting (how shall we say?) relationships in the data.

For example, OkCupid’s site metrics (number of new conversations started per hour) were far beneath a typical Tuesday’s during the peak hours of 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. It seems that without the ability to view a prospective date’s photo, users were less motivated to make an initial inquiry. Nevertheless, Rudder reports that the conversations initiated during these seven hours without photos went deeper and contact details (e.g., email addresses and phone numbers) were exchanged more quickly. Sadly though, when the photos were restored at 4 p.m. sharp, the 2,200 users who were in the middle of their conversations that had started “blind” dissipated. As Rudder puts it, restoration of the photos was like turning on the bright lights at the bar at midnight. Conversations that had consisted of two messages prior to the 4 p.m. bewitching hour witnessed the largest drop relative to normal.

Curious about the extent to which a person’s photo matters on OkCupid, Rudder performed a simple test based upon a randomly chosen subsample of users. Half of the time their pages were accessed by a prospective suitor, their profiles were kept hidden. And half of the time the profiles were not hidden. This generated two independent sets of ratings for each member of the sample—one rating when the picture and profile text were presented together, the other for when the picture was presented alone. Rudder found a strong positive correlation between the ratings with and without the profile text included, suggesting that a picture really is worth a thousand words. A person’s rating was driven by the appeal of their picture rather than their profile. To put it less sanguinely, we Homo sapiens tend to be superficial when it comes to choosing our dating partners.[6]

The Spillover of Racialization

To what extent might racial prejudice spill over into (i.e., infect) opinions about public policy, such as health care and fiscal stimulus? The election of Barack Obama in 2008 as the 44th President of the United States helps provide an answer. Using data from a nationally representative survey experiment, Tesler (2012) documents the impact of race and racial attitudes on opinions concerning national healthcare policy before and after Obama’s election. The authors find that racial attitudes were both an important determinant of White Americans’ opinions about healthcare policy in the fall of 2009 and that the influence of these attitudes increased significantly after President Obama became the face of the policy. Results from the experiment show that racial attitudes had a significantly greater impact on healthcare opinions when framed as part of President Obama’s plan than they had when the same policies were attributed to President Clinton’s 1993 healthcare initiative. In other words, Tesler uncovers what he calls a spillover of racialization, which situates Obama’s race—and the public’s race-based reactions to him—as the primary reason why public opinion about national healthcare policy racialized in the fall of 2009.

As Tesler points out, spillover of racialization—whereby racial attitudes have a bearing on political preferences—is rather straightforward for race-targeted public policies such as affirmative action and federal aid to minorities. These types of issues are thought to readily evoke racial predispositions since a natural associative link exists between policy substance and feelings toward the groups who benefit from them. However, this link is not as readily apparent for broader issues such as healthcare and fiscal stimulus.

Tesler further avers that, after receiving little media attention during the first half of 2009, the debate over healthcare reform became one of the most reported news stories in America from early July through the remainder of the calendar year, so much so that roughly half of Americans reported following the healthcare reform debate very closely in 2009 (Pew Research Center, 2009). If, as the spillover of racialization hypothesis contends, Obama’s connection to the issue helped racialize their policy preferences, then the effect of racial attitudes on White Americans’ opinions should have increased from before to after his healthcare reform plan was subjected to such intense media scrutiny.

Tesler utilizes observational data from repeated cross-sectional surveys conducted by the American National Election Study (ANES). The ANES healthcare question asks respondents to place themselves on a seven-point government-to-private insurance preference scale. To obtain corresponding information on racial resentment, Tesler re-interviewed individuals who had participated in the ANES survey both before and after President Obama’s election. The author argues that his racial-resentment measure taps into subtle hostility among White Americans toward Black Americans. The measure is based upon four questions about Black work ethic, the impact of discrimination on Black American advancement, and notions of Black people getting more than they deserve—themes thought to undergird a symbolic racialism belief system—and coalesced into a seven-point scale from low to high levels of racial resentment.

Tesler finds that, for White respondents, moving from those harboring the least amount of racial resentment to those harboring the most resentment increased the proportion of those saying that the national healthcare system should be left up to individuals by approximately 30 percentage points (from 10% to 40%) in December 2007, when President Clinton was the face of national healthcare policy. However, the same change in these individuals’ resentment levels (i.e., again moving from those White respondents harboring the least amount of racial resentment to those harboring the most resentment) increased their support for private insurance by roughly 60 percentage points (from 10% to 70%) in November 2009, when President Obama served as the face of the same national healthcare policy—a statistically significant difference. This leads Tesler to conclude that with the election of President Obama racial attitudes became more important in White Americans’ beliefs about healthcare relative to nonracial considerations like partisanship and ideology.

In an additional experiment, Tesler investigated opinions regarding the $787 billion economic stimulus package passed by Congress in 2009. Respondents were divided into two subsets. In one subset, respondents were asked if they thought the stimulus package approved by congressional Democrats was a good or bad idea, the other was asked the same question but with approval instead being granted by President Obama. The author finds that moving from least to most racial resentment decreased the proportion of White respondents saying that the stimulus program was a good idea by less than 10 percentage points when congressional Democrats are identified as the approving authority, but by approximately 70 percentage points when President Obama is identified as the approving authority. In other words, the incidence of racialization spillover is even more profound than it was regarding national healthcare policy.

Awareness Reduces Racial Discrimination

In situations where racial discrimination is known to exist, does informing the public of its existence encourage perpetrators to repudiate its practice? Pope et al. (2018) devised a novel approach to answer this question. In 2003, the authors began by analyzing data from the National Basketball Association (NBA) for the years 1991-2003. They found that White and Black players received relatively fewer personal fouls when more of the referees officiating the game were of their own race. This in-group favoritism (or, alternatively stated, out-group racial bias) displayed by NBA referees was large enough to influence game outcomes.

In May of 2007, the results of this study received widespread media attention—front-page coverage in the New York Times and many other newspapers, and extensive coverage on major news networks, ESPN, and talk radio. Subsequently, the authors analyzed NBA data for the years 2007–2010 and found an absence of this out-group racial bias, although other biases were found to persist (e.g., referees tend to favor the home team, the team that is losing in a given game, and teams that are losing the game count in a playoff setting).

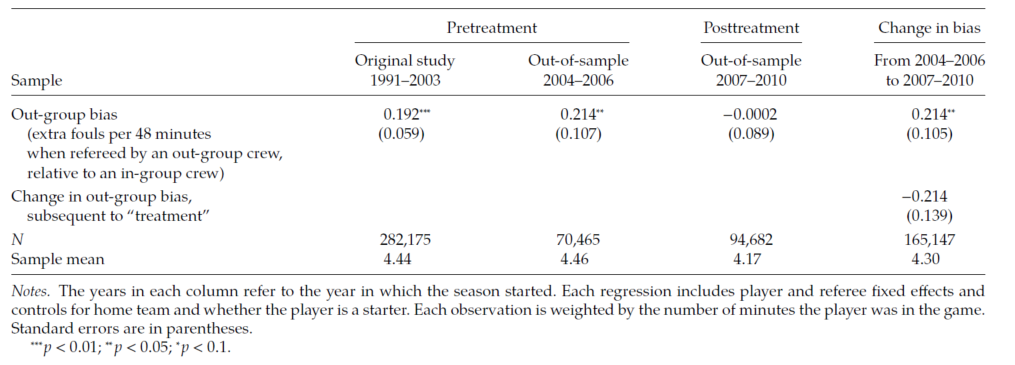

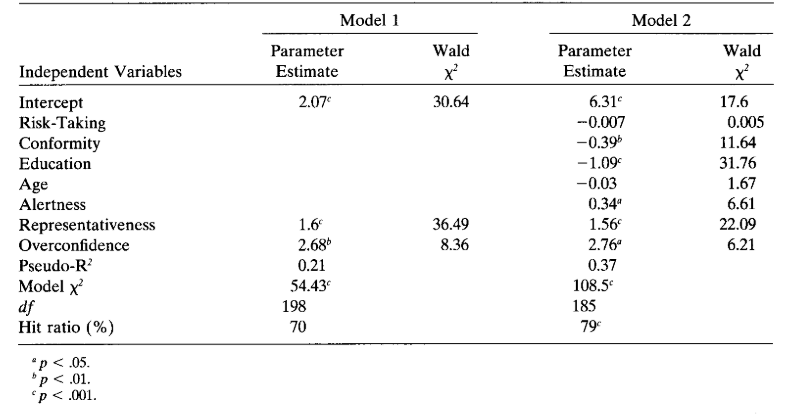

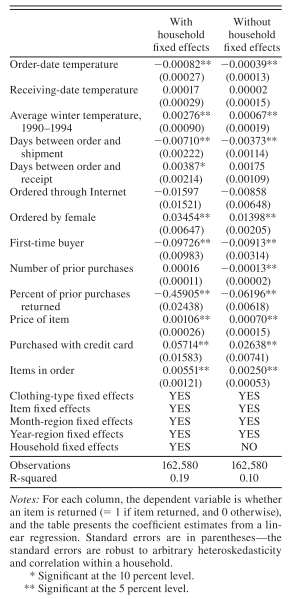

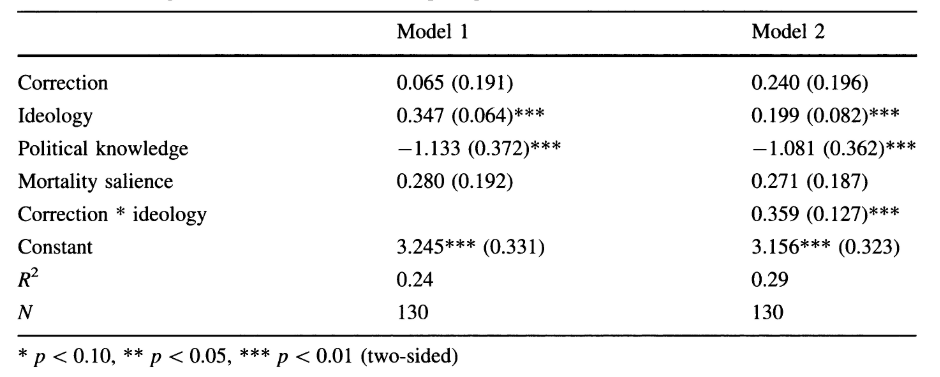

The table below contains Pope et al.’s (2018) specific findings:

Similar to the presentation of Levitt’s (2004) results (see Discrimination in The Weakest Link Game Show above), marginal effects are presented with their corresponding standard errors in parentheses. Pope et al. provide additional notation to distinguish statistically significant effects from those that are not—superscripts with more asterisks indicate more statistical significance; those effects without any asterisks indicate no statistical significance. The marginal effects in the pretreatment period—based upon data from the original study and an additional study covering the years 2004-2006—are positive and statistically significant (0.192 and 0.214, respectively), leading the authors to conclude that, prior to media attention, significantly more fouls were called on Black players when the referee crew was predominantly White. In the post-treatment period—based upon data from 2007-2010—the marginal effect is not statistically significant (i.e., no effect exists). Hence, the prior racial bias among referee crews in the NBA dissipated after having received widespread media attention. That’s a slam dunk for the NBA and another one for Homo sapiens in general! Raising awareness of racial discrimination, especially when we can quantify its presence, serves as a nudge toward racial equality.

Improving Student Performance

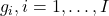

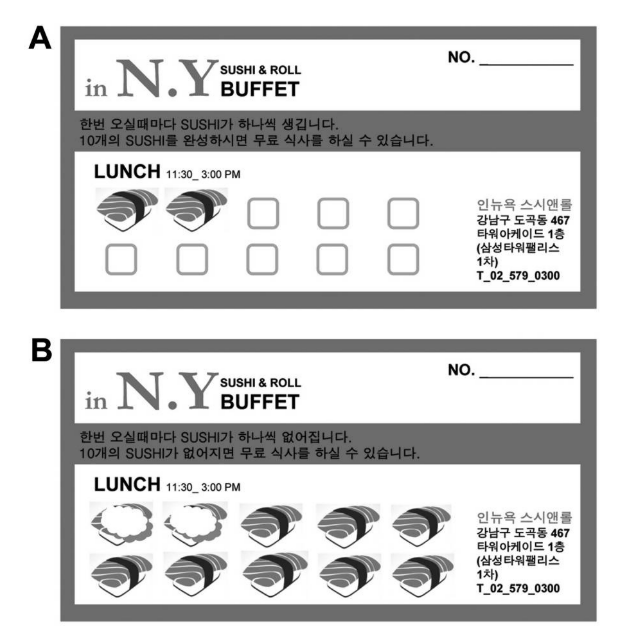

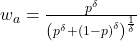

Levitt et al. (2016) designed a field experiment to test the effects of different incentive mechanisms on the academic performance of students in low-performing elementary, middle, and high schools in the Chicago public school system and, in the process, test for the existence of loss aversion and time inconsistency among the students. Students were offered one of the following rewards for improving upon a previous (baseline) computerized reading or math test: $10 in cash (“financial low”), $20 in cash (“financial high”), or a trophy and posting of a student’s photograph in the school’s entrance (“nonfinancial”).

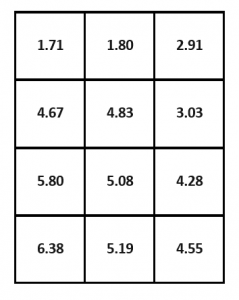

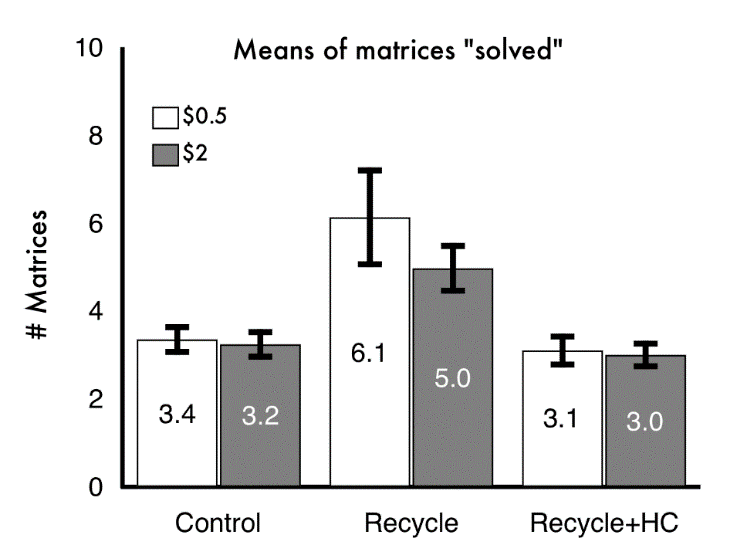

To test for loss aversion among the students, financial and non-financial rewards were delivered in one of two ways: (1) the test administrator held up the $10 bill, $20 bill, or trophy at the front of the room before the test began (the authors call this the “gain condition”), or (2) students received the $10 bill, $20 bill, or trophy at the start of the testing session and were informed that they would keep the reward if their performance improved and lose the reward if it did not (“loss condition”). The following results were obtained:[7],[8]

- The $20 incentive (framed either as a gain or loss) delivered immediately after students completed the test increased the average student’s test score. The $10 incentive did not increase the average student’s test score and even lowered performance on future tests.

- The trophy delivered immediately after the test increased the average student’s test score less dramatically than the $20 incentive. Scores increased most dramatically for younger students who received trophies.

- The average student’s test score increased more in the loss condition than in the gain condition, but the difference is not statistically significant. Hence, the average student does not exhibit loss aversion with respect to how the reward for improved performance is distributed.

- Delayed rewards (delivered one month after completion of the exam rather than immediately) did not increase the average student’s test score. This suggests the existence of hyperbolic discounting, where rewards delayed in the near term are discounted at an excessively high rate (recall our earlier exploration of this phenomenon in Chapter 4).

- Overall, math scores increased more than reading scores across all students. Boys increased their scores in these subjects more than girls.

Improving Teacher Performance

Fryer et al. (2022) demonstrate that, unlike Levitt et al.’s (2016) findings for elementary and middle school students in Chicago, exploiting the power of loss aversion—where the student’s teachers are paid at the beginning of the school year and asked to give back the money if their students do not improve sufficiently (loss treatment)—leads to statistically significant increases in their students’ math test scores. A second treatment identical to the loss treatment but with year-end bonuses linked to student performance (gain treatment) yields smaller and statistically insignificant results. The authors conclude that because teachers exhibit loss aversion (in terms of rewards tied to their students’ academic performance), a loss-treatment approach is the most effective way to incentivize teachers to improve student performance.

In specific, Fryer et al. find that, all else equal, the average student who was taught by a teacher who had been randomly assigned to the loss treatment gained (statistically significant) percentile-ranking points relative to her nine nearest students during the math exam; gains that persisted in time after the treatment. Students who were taught by teachers who were randomly assigned to the gain treatment showed markedly lower and statistically insignificant gains. Therefore, it seems as though a teacher’s performance can be more effectively nudged by appealing to his sense of loss aversion rather than merely the teacher’s desire for gain.

Healthcare Report Cards

Recall from Chapter 8 the simultaneous-move game where provisioning one of two players with additional information actually perversely affected the game’s analytical equilibrium. The message was clear. The rational choice model’s tenet that more information leads to improved performance is not universal. Especially when it comes to the experience of Homo sapiens, situations where the provision of additional information leads to a perverse outcome are not necessarily in short supply.

Dranove et al. (2003) provide a seminal example with their study of Healthcare Report Cards—public disclosure of patient health outcomes at the level of the individual physician or hospital or both—that are intended to improve the performance of healthcare providers. In their study, the authors analyzed New York’s and Pennsylvania’s publications of physician and hospital coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery mortality rates in the 1990s. At the time, the merits of these types of report cards were in much debate. Supporters argued that report cards enable patients to identify the best physicians and hospitals while simultaneously giving healthcare providers powerful incentives to improve quality. Skeptics countered that report cards encourage providers to “game” the system by avoiding sick patients and/or seeking healthy patients.

As Dranove et al. point out, low-quality providers have strong incentives to avoid the sick and seek the healthy under this type of reporting system. By shifting their practice toward healthier patients, inferior providers make it difficult for report cards to distinguish them from their higher-quality counterparts because relatively healthy patients have higher likelihoods of better outcomes regardless of provider. As the authors put it, low-quality providers can therefore pool with their high-quality counterparts, making it more difficult for the report cards to distinguish between the two.

Spoiler alert: The authors find that while the report card system increased the quantity of CABG surgeries among patients suffering from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (i.e., heart attacks), it changed the surgery’s incidence from sicker AMI patients toward healthier AMI patients. Overall, this led to higher costs and deterioration of outcomes, especially among the sicker AMI patients (i.e., the report cards were welfare-reducing).

Dranove et al. find that the introduction of report cards increased the probability that the average AMI patient would undergo CABG surgery within one year of hospital admission by between 0.60 to 0.91 percentage points. As the authors point out, these report-card effects are considerable, given that the probability of CABG within one year for an elderly AMI patient during their sample period was approximately 13%. However, the report-card effects did not occur immediately (i.e., within one day of admission to the hospital). Indeed, the immediate report-card effect is estimated to have been negative for the average AMI patient (ranging from -0.59 to -0.78 percentage points). The authors also find evidence to suggest that the report card system led to sicker patients being less likely to undergo CABG surgery within one year of admission. Report-card effects on average (1) led to increases in total hospital expenditures in the year after admission of an AMI patient, (2) provided some evidence of increased patient readmission with heart failure within one year, and (3) provided some evidence of increases in mortality within one year of admission. These perverse welfare effects were particularly strong among sicker AMI patients.

This is one of several examples in the empirical literature of perverse outcomes associated with what, on the surface, would seem to be naturally beneficial incentives, or nudges, meant to improve the social welfare of Homo sapiens, in this case with respect to health care.

Losing Can Lead to Winning

Berger and Pope (2011) conducted another study using data from the NBA, this time seeking to determine if teams who, going into halftime of a typical game and down a certain number of points, collectively exhibit loss aversion—in terms of not wanting to lose the game—by winning the game in the end. In other words, do NBA players demonstrate loss aversion collectively as a team?

The authors analyzed more than 18,000 NBA games played from 1993-2009 and found that teams behind by one point at halftime win more often than teams ahead at halftime by one point—approximately 6% more often than expected. This finding suggests the presence of (1) loss aversion—being behind at halftime motivates a team not to lose more than being ahead at halftime motivates a team to win, (2) diminishing sensitivity—the losing team cannot be too far behind at halftime, and (3) reference dependence—being behind at halftime helps the losing team establish the goal of winning.[9]

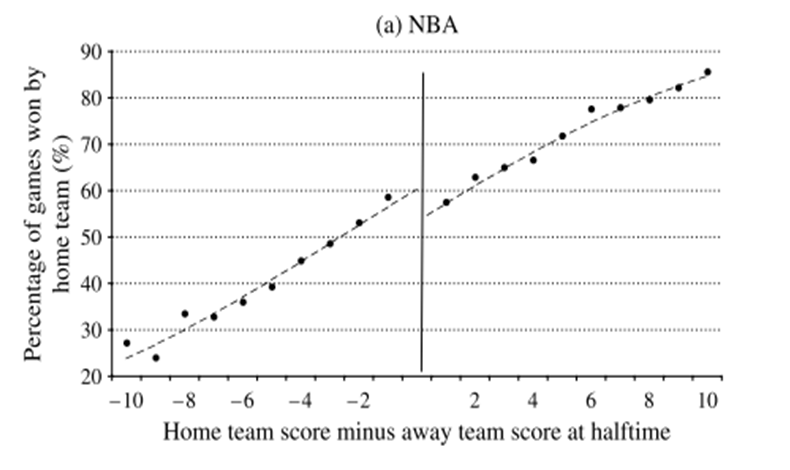

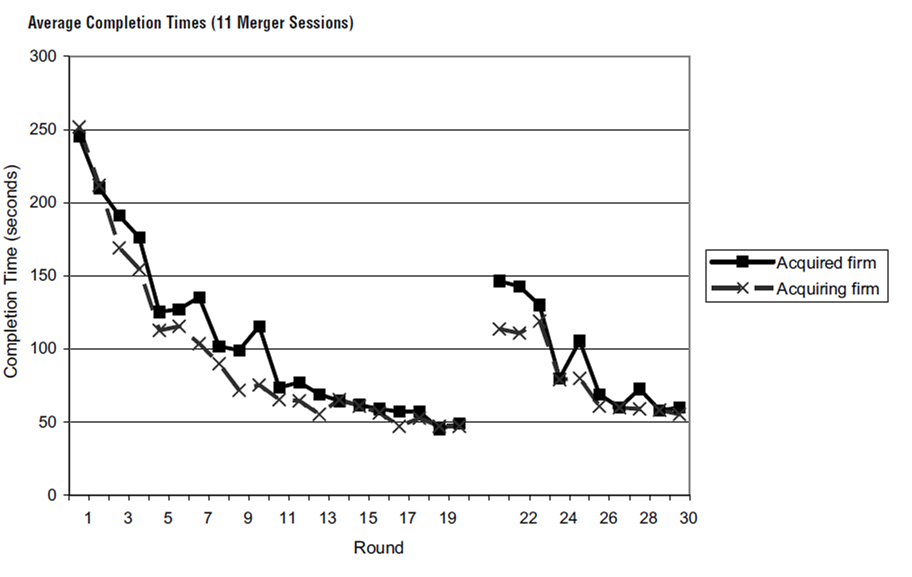

The graph below depicts Berger and Pope’s results:

The upward slope of the hashed line indicates that the more points the home team has at halftime relative to the away team, the more likely the home team will wind up winning the game. The line’s discontinuity in the neighborhood of zero depicts the study’s main results. At one point behind, the probability of the home team winning is roughly 60%. At one point ahead, the home team’s probability of winning drops to roughly 54%, which is slightly higher than if the home team is down by two points at halftime. Similarly, if the home team is ahead by two points at halftime, then its probability of winning is over 60%. Hence, when two teams are within a few points of each other going into halftime, halftime is indeed a game’s reference point. And the home team’s chances of winning the game diminishes fairly rapidly as it falls further behind going into halftime. This latter result can be taken as evidence that a home team’s collective marginal disutility of losing diminishes in concert with its chances of winning. Berger and Pope also find that, all else equal, when the home team is losing at halftime, its probability of winning the game increases by anywhere from 6% to 8%.

Loss Aversion in Professional Golf

Professional basketball is not the only sport lending itself to empirical testing of behavioral economics’ preeminent theories. Professional golf is also amenable. Using data on over 2.5 million putts measured by laser technology, Pope and Schweitzer (2011) test for the presence of loss aversion among professional golfers competing on the Professional Golf Association (PGA) Tour. As the authors point out, golf provides a natural setting to test for loss aversion because golfers are rewarded for the total number of strokes they take during a tournament, yet each individual hole has a salient reference point, par.

Pope and Schweitzer find that when golfers are “under par” (e.g., putting for a “birdie” that would earn them a score one stroke under par), they are 2% less likely to make the putt than when they are putting for par or are “over par” (e.g., putting for a “bogey” that would earn them one stroke over par). Even the best golfers—including Tiger Woods at the time—show evidence of loss aversion in these situations. Loss aversion motivates golfers to make a higher percentage of puts when they are putting for a bogey than a birdie.

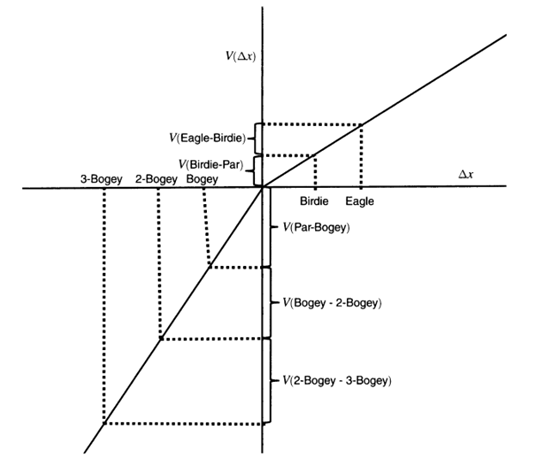

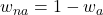

Two figures coalesce the authors’ econometric results. The first figure represents the typical golfer’s value function. Note the function’s reference point (i.e., its origin) at par. The steeper portion of the function defined over the disutility region is associated with missing par and thus bogeying a putt (one-over-par is a bogey, two-over-par is a double bogey, and so on). The flatter portion of the function defined over the utility region corresponds to scoring under par with a birdie (one under par), eagle (two under par), or albatross (greater than two under par). Recall that the relative steepness of the function in the disutility region depicts loss aversion. The linearity of the function indicates an absence of the diminishing effect.

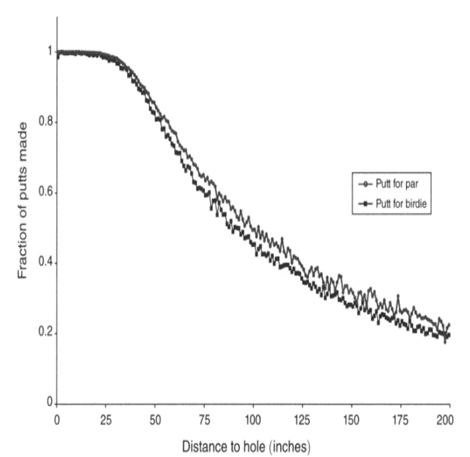

The next figure depicts the relationships between the average golfer’s fraction of putts made when putting for par and for birdie, respectively, relative to distance from the hole. As expected, regardless of whether a golfer is putting for birdie or par, the fraction of putts made decreases as the distance to the hole increases. Of particular interest in this study is that, at each distance, the fraction of putts made is less when the golfer is putting for birdie as opposed to par—again, evidence of loss aversion.

To reiterate, this study’s main econometric results reveal a negative effect on sinking a putt when the typical golfer is putting for birdie, and a positive effect on putting for bogey. Consistent with the previous graphs, these numerical results suggest that the typical professional golfer is more likely to sink a put for bogey and less likely to sink the putt for birdie (i.e., the typical golfer is indeed loss averse).[10]

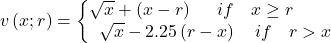

Are Cigarette Smokers Hyperbolic Time Discounters?

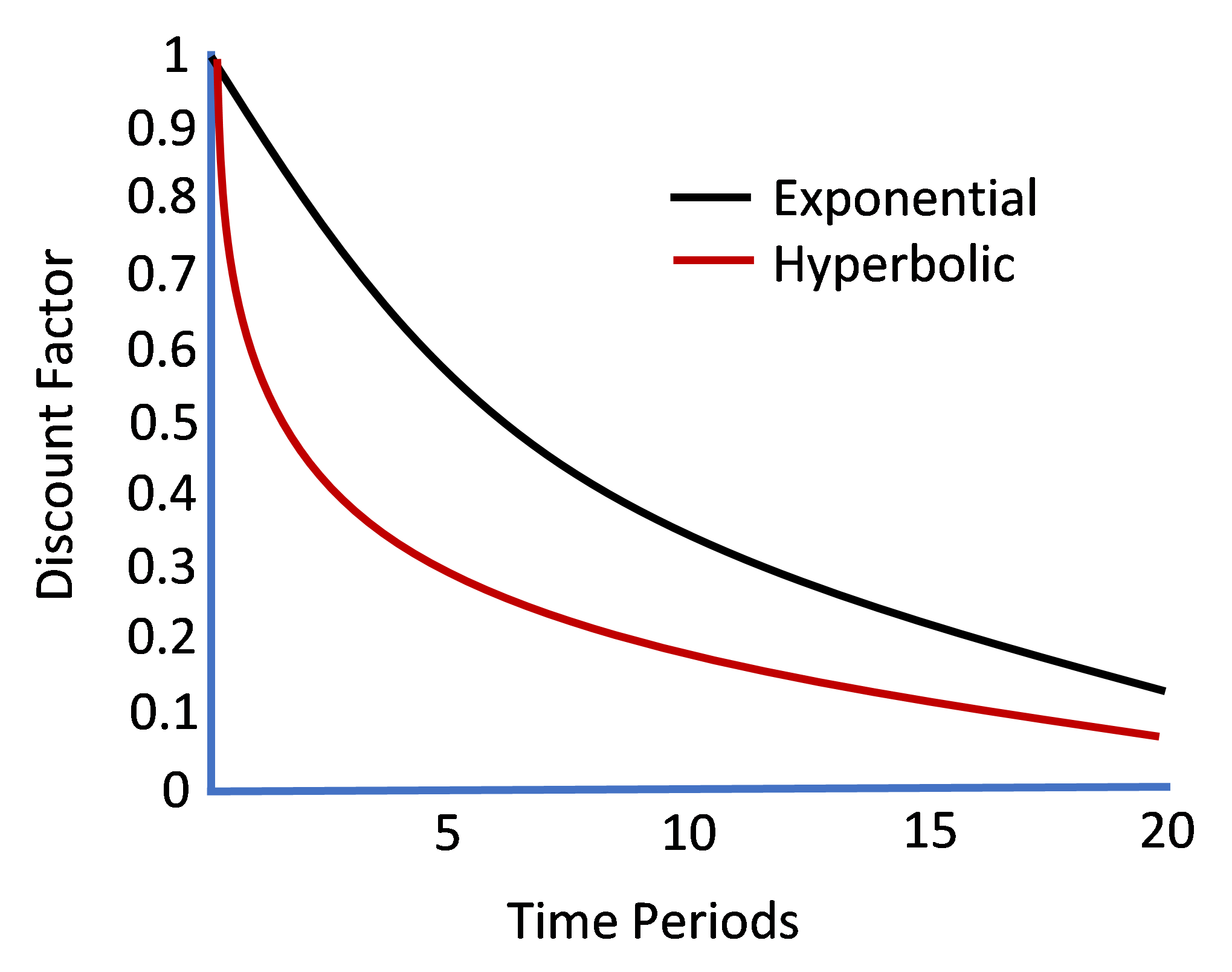

Recall from Chapter 4 the distinction between time-consistent exponential time discounters (Homo economicus) and potentially time-inconsistent hyperbolic discounters (Homo sapiens). The discounting time paths for exponential versus hyperbolic discounting looked like this:

A feature distinguishing a hyperbolic from an exponential time discounter is that the former discounts time delays in near-future consumption at much higher rates than the latter, but the discounting of more distant-future consumption converges between the two.

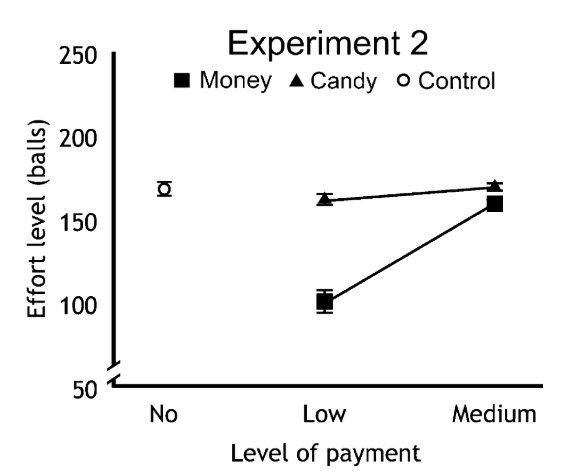

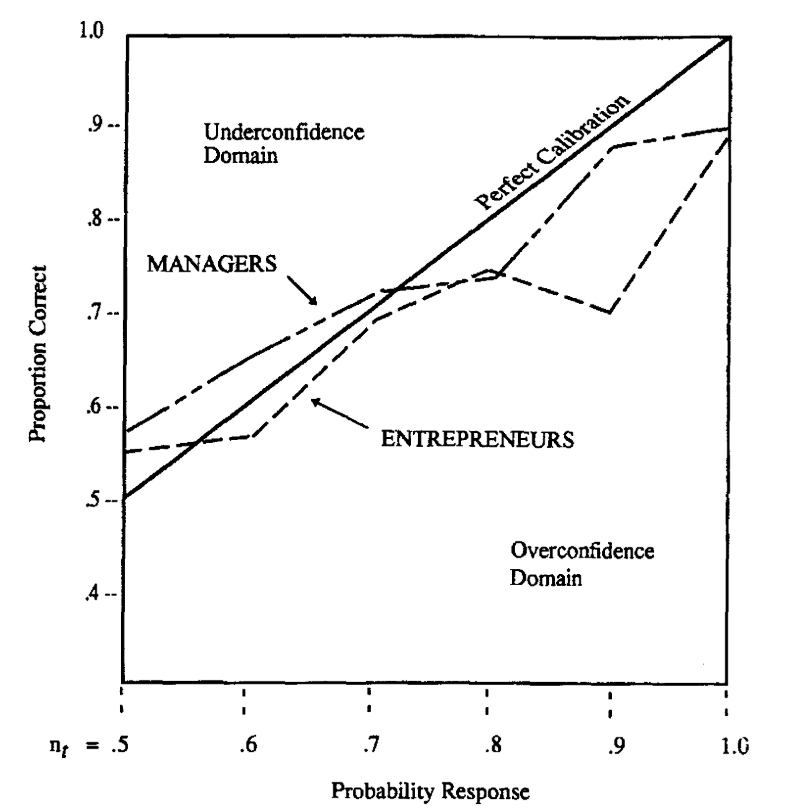

In contrast with Becker and Murphy’s (1988) early theoretical work explaining rational addiction among Homo economicus based upon exponential time discounting, experimental research aimed at explaining addiction among Homo sapiens has found that hyperbolic discounting of future consumption can at least partially explain the impulsive behavior exhibited by those among us with addictions to drugs such as alcohol, heroin, and opioids (c.f., Vuchinich and Simpson, 1998 and Madden et al., 1997).[11] Bickel et al. (1999) also find evidence of hyperbolic time discounting among cigarette smokers. In their field experiment, the authors compare the discounting of hypothetical monetary payments by current and ex-smokers of cigarettes, as well as those who have never smoked (henceforth “never smokers”). For current smokers, the authors also examine discounting behavior associated with delayed hypothetical payment in cigarettes.[12], [13]

The authors find that current smokers discount the value of a delayed monetary payment more than ex- and never-smokers (the latter two groups do not differ in their discounting behaviors). For current smokers, delayed payment in cigarettes loses subjective value more rapidly than delayed monetary payment. The hyperbolic equation provides a better fit of the data for cigarette smokers than the exponential equation for 74 out of the 89 different comparisons between current cigarette smokers, on the one hand, and ex- and never-smokers on the other. Bickel et al. (1999) conclude that cigarette smoking, like other forms of drug dependence, is characterized by rapid loss of subjective value for delayed outcomes (i.e., pronounced hyperbolic discounting).

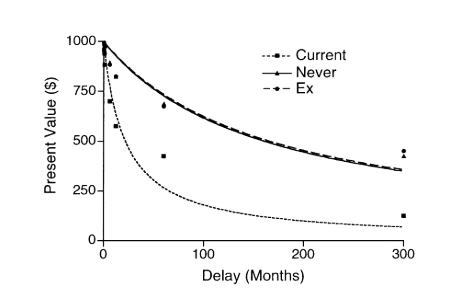

The figure below shows Bickel et al.’s results for a monetary payment scheme. The curves represent the median indifference points (i.e., the estimated values of immediate payment at the respective points of subjective equality with each of seven different delay periods) for current smokers, never-smokers, and ex-smokers. We see that the subjective values decrease more rapidly for smokers (along the curve resembling a hyperbolic discounting function) than for never-smokers and ex-smokers (along curves resembling exponential discounting functions). For example, for smokers, a $1000 payment lost 42.5% of its value when delayed by one year, but for never- and ex-smokers, a $1000 payment lost only 17.5% of its value when delayed by one year.

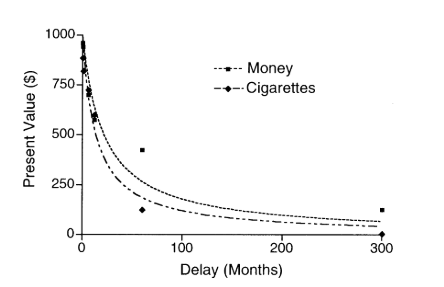

As the figure below shows, the bulge in current smokers’ hyperbolic discounting function is more pronounced for the cigarette payment scheme (the curve associated with the monetary payment scheme is reproduced from the previous figure for ease of comparison).

Arrest Rates and Crime Reduction

As Levitt (1998) points out, the linchpin of the rational-choice model of crime is the concept of deterrence: criminal Homo economicus will choose to commit fewer criminal acts when faced with higher probabilities of detection or more severe sanctions. Levitt conjectures that criminal Homo sapiens may defy this rational-choice model of deterrence by being poorly informed about the likelihood of getting caught, over-optimism about their abilities to evade detection, myopia due to the time gap between committing the crime and imprisonment, or perhaps because serving a prison sentence satisfies a rite of passage among a criminal’s peers.

Levitt further points out that empirically testing for a deterrence effect among would-be criminals is fraught with challenges because increasing the expected punishment associated with a given crime can potentially reduce crime through two different channels. The first channel is deterrence—larger penalties and/or higher arrest rates induce criminals to commit fewer crimes. The second channel is incapacitation—if criminals commit multiple offenses and punishment takes the form of imprisonment, increasing expected punishment will also reduce crime by getting criminals off the streets. While a criminal is imprisoned, he is unable to engage in criminal actions that otherwise would have taken place, which biases the statistical effect of deterrence upward (i.e., due to the incapacitation effect, an increase in deterrence measures undertaken by the police would be identified as having a larger negative impact on crime reduction than is truly the case).

Levitt utilized annual reported-crime data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for 59 of the largest U.S. cities over the period 1970-1992 to test for a deterrence effect driven by changes in arrest rates. His results suggest that (1) incapacitation predominately reduces the incidence of rape, (2) incapacitation and deterrence effects are of equal magnitude in reducing the incidence of robbery, and (3) the deterrence effect outweighs the incapacitation effect in reducing aggravated assault and property crimes (Levitt estimates that the deterrence effect accounts for more than 75% of the observed effect of arrest rates on property crime).

Hence, when it comes to arrest rates, criminal Homo economicus and Homo sapiens share similar responses to deterrence.

Interpersonal Dynamics in a Simulated Prison

There is substantial evidence that prisons in the US (if not worldwide) neither rehabilitate prisoners nor deter future crime. In its most recent report on recidivism in the US, the US Justice Department reports that 44% of state prisoners released in 2005 across 30 states were re-arrested within one year of their release, 68% within four years, 79% within six years, and 83% within nine years (Alper et al., 2018). Of released drug offenders, 77% were re-arrested for a non-drug crime within nine years after release. During each year, and cumulatively during the nine-year follow-up period, released non-violent offenders were more likely than released violent offenders to be arrested again (Alper et al., 2018).

Haney et al. (1973) pose (and then seek to answer) a nagging question pertaining to what lies behind these statistics. To what extent can the deplorable conditions of our penal system and their often-dehumanizing effects upon prisoners and guards—conditions that likely contribute to recidivism—be explained by the nature of the people who administer it (prison guards) and the nature of the people who populate it (prisoners)? The authors’ dispositional hypothesis is that a major contributing cause of these conditions can indeed be traced to some innate or acquired characteristics of the correctional and inmate populations. As the authors point out, the hypothesis has been embraced by both the proponents of the prison status quo, who blame the nature of prisoners for these conditions, as well as the status quo’s critics, who blame the motives and personality structures of guards and staff.

To understand the genesis of prison culture—in particular, the cultural effect on the disposition of both prisoners and guards—Haney et al. (1973) undertook one of the most notorious (or, depending upon one’s perspective, noteworthy) field experiments ever conducted with willing, non-incarcerated adults. The authors designed a functional simulation of a US prison in which subjects who were drawn from a homogeneous, “normal” sample of male college students role-played prisoners and guards for an extended period of time. Half the subjects were randomly assigned to the prisoner group, which was incarcerated for nearly one full week. The other half were randomly assigned to the prison guard group, which played its role for eight hours each day. The behaviors of both groups were observed, recorded, and analyzed by the authors, particularly regarding transactions occurring between and within each group of subjects.

The 21 subjects who ultimately participated in the experiment (out of a total of 75 applicants) were judged to be the most physically and emotionally stable, most mature, and exhibited the least anti-social behavior. The prison was constructed in a basement corridor in the Psychology Department’s building at Stanford University. It consisted of three small cells (6’ x 9’), each cell housing three prisoners. A cot, mattress, sheet, and pillow for each prisoner were the only pieces of furniture in each cell. A small, unlit closet across from the cells (2’ x 2’ x 7’) served as a solitary confinement facility. Several rooms in an adjacent facility were used as guards’ rooms and quarters for a “warden” and “superintendent.” The prisoners were each issued identical, ill-fitting, prisoner uniforms to instill uniformity and anonymity in the prisoners’ daily existence. The guards’ uniforms consisted of a plain khaki shirt and trousers, a whistle, wooden baton, and reflecting sunglasses that made eye contact impossible.

With help from the Palo Alto City Police Department, the prisoners were each “arrested” (with handcuffs, no less) at their residences under suspicion of burglary and armed robbery, taken to the police station, and “processed” under normal induction procedures. Once they arrived at the simulated prison (blindfolded, no less), they continued with standard induction procedures, which included being stripped naked, sprayed with a deodorant, and made to stand alone naked in a prison yard for a short period of time. Each prisoner was then put in his cell and ordered to remain silent. During their confinement, the prisoners were fed three meals a day, allowed three supervised toilet visits, and were allotted two hours daily for the privilege of reading and letter-writing.

Data was gathered via videotaping, audio recordings, personal observations, and a variety of checklists filled out by the guards and researchers. Through subsequent analysis of the data, Haney et al. (1973) found that the personal behaviors of the prisoners and guards, and the social interactions between them, supported many commonly held conceptions of prison life and validated anecdotal evidence provided by real-life ex-convicts. In general, both prisoners and guards tended toward increased negativity over the week in terms of their dispositions. For both prisoners and guards, self-evaluations became more disapproving as their experiences were internalized. Prisoners generally adopted a passive response mode while guards assumed active, initiating roles in all prisoner-guard interactions.[14]

Specifically, Haney et al. found that the extent to which a prisoner scored high on his personality test for rigidity, adherence to conventional values, and acceptance of authority helped determine the likelihood that he adjusted more effectively to the authoritarian prison environment. In written self-reports, prisoners expressed nearly three times as much negativity as positivity. Guards expressed slightly more negativity than positivity. Prisoners also showed roughly three times as much mood fluctuation as did the guards.

Haney et al. conclude:

“The conferring of differential power on the status of “guard” and “prisoner” constituted, in effect, the institutional validation of those roles. But further, many of the subjects ceased distinguishing between prison role and their prior self-identities. When this occurred, within what was a surprisingly short period of time, we witnessed a sample of normal, healthy American college students fractionate into a group of prison guards who seemed to derive pleasure from insulting, threatening, humiliating, and dehumanizing their peers—those who by chance selection had been assigned to the prisoner role. The typical prisoner syndrome was one of passivity, dependency, depression, helplessness and self-deprecation.” (p. 89)

For those of us who are skeptical of the simulated nature of this experiment’s constructed prison environment, Haney et al. offer this final thought:

“In one sense, the profound psychological effects we observed under relatively minimal prison-like conditions which existed in our mock prison make the results even more significant and force us to wonder about the devastating impact of chronic incarceration in real prisons.” (p. 91)

At the very least, this experiment demonstrates how manipulatable and culpable Homo sapiens can become in the context of a field experiment.[15]

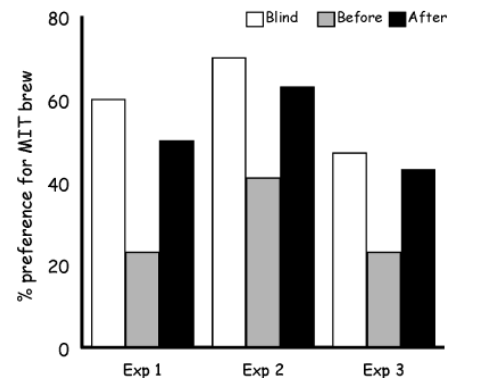

Corruption in Sumo Wrestling

In one of their most well-known studies, Duggan and Levitt (2002) uncovered the extent of corruption in Japan’s national sport, sumo wrestling. To understand how they did so, one must know something about how sumo wrestling tournaments work.

A sumo tournament involves 66 wrestlers (rikishi) competing in 15 bouts each. A wrestler who achieves a winning record (eight wins or more) in a tournament is guaranteed to rise in the official ranking of the nation’s wrestlers. A wrestler with a losing record in the tournament (seven wins or less) falls in the national rankings. A wrestler’s ranking is a source of prestige and the basis for salary determination and various in-kind perks.

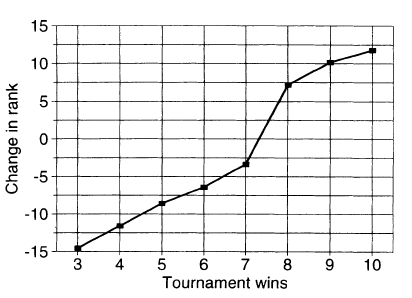

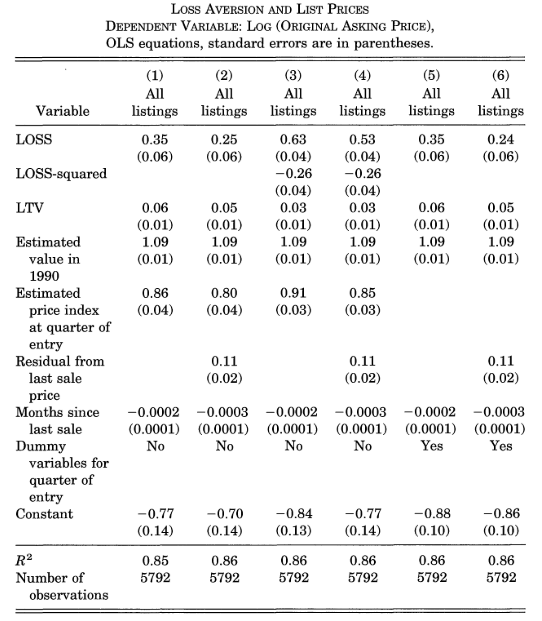

As Duggan and Levitt point out, the key institutional feature of sumo wrestling making it ripe for corruption is the concomitant nonlinearity in the ranking (and thus payoff) function for competitors, depicted in the figure below:

We see that a wrestler who achieves a losing record of seven wins and eight losses (7-8) can expect to drop in the rankings by roughly three places (e.g., if, going into the tournament, the wrestler was ranked third nationally, after the tournament, he is now ranked sixth). To the contrary, a wrestler achieving a winning record of 8-7 in the tournament can expect to rise in rank by roughly eight places. Consequently, a wrestler entering the final match of a tournament with a 7-7 record has far more to gain from a victory than an opponent with a record of, say, 8-6 has to lose.

Following almost 300 wrestlers from 1989-2000, the authors find that wrestlers who are on the margin for attaining their eighth victory in a given tournament (in what’s known as a “bubble match”) win far more often than one would expect. Further, whereas the wrestler who is on the margin for his eighth victory in a bubble match wins with a surprisingly high frequency, the next time the same two wrestlers face each other in another tournament, it is the opponent (i.e., the wrestler who threw the bubble match) who has an unusually high win percentage. In other words, Duggan and Levitt not only uncover corruption in the bubble match itself but also corruption in the subsequent match between the same two wrestlers. This corruption comes in the form of the earlier bubble match’s winner duly compensating the loser by similarly throwing the current match.

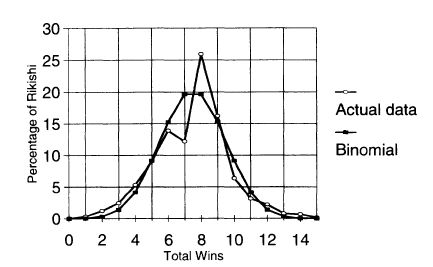

Duggan and Levitt depict their finding in the figure below:

The figure shows two curves—one based on the actual data, the other based on the binomial distribution, which represents the distribution we would expect to hold between the wrestlers and their wins, all else equal. The binomial distribution depicts a nice, bell-shaped curve where the largest percentages of wrestlers win between 5 and 10 matches per tournament. The obvious spike in the actual data over eight wins, which is aligned with over 25% of the wrestlers when we would expect only 20%, suggests a preponderance of unexpected outcomes in bubble matches.

Interestingly, Duggan and Levitt find that the bubble match effect disappears in tournaments with high levels of media scrutiny and when the opponent (i.e., the wrestler who would otherwise agree to throw the bubble match) is in the running for one of the tournament’s special prizes.[16] By contrast, success on the bubble increases for veteran wrestlers (i.e., all else equal, veterans are more likely to win bubble matches in tournaments where they go into the match with seven wins, seven losses).

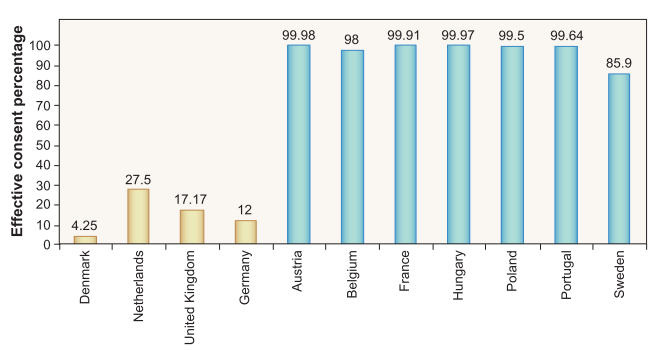

Corruption in Emergency Ambulance Services

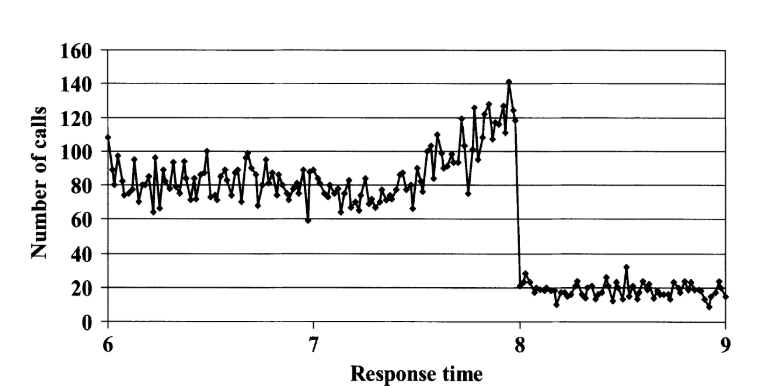

To improve emergency ambulance response times in England in the early 2000’s, authorities implemented a common response-time target for “ambulance trusts” (i.e., regional units) that 75% of potentially immediately life-threatening (Category A) emergency telephone calls be met within 8 minutes of the call having been placed. Less serious emergency calls (e.g., concerning serious but not life-threatening or neither serious nor life-threatening) were assigned less stringent targets. In addition, a “star rating system” was established rewarding or penalizing the trusts based upon the extent to which they met or did not meet the targets.

As Bevan and Hamblin (2009) point out, hospital rankings based upon the annual star ratings were easy to understand, and the results were widely disseminated (published in national and local newspapers and on websites, and featured on national and local television). Hospital staff was highly engaged with the information used to determine the ratings. Further, the star ratings mattered for chief executives, as being zero-rated resulted in damage to their professional reputations and affected staff recruitment. As a result, the star rating system was widely considered to be a salient mechanism for improving hospital performance and, as a result, was ripe for attempts by hospitals and ambulance trusts to manipulate it.

Bevan and Hamblin find that, on the surface, the implementation of Category A ambulance-service targets in 2002 had a noticeable impact on response times. The percentage of response times per trust meeting the eight-minute target increased markedly after 2002 and remained up in the range of 70%–90% meeting the target through the study period of 2005.

However, digging deeper into the data, Bevan and Hamblin uncovered pervasive evidence of cheating among the trusts. As the authors point out, the system’s intense focus on the Category A target gave rise to several concerns, among them the obvious incentive to classify calls as Categories B and C rather than Category A, and the fact that arriving at the scene in 8.01 minutes was now inevitably seen as a failure. Earlier investigations had concluded that the former concern—reduced number of calls classified as Category A—was not commonly practiced among the trusts. Not so the latter concern. Bevan and Hamblin find that among the trusts’ response times taking longer than the targeted eight minutes, roughly 30% had been ‘corrected’, i.e. re-recorded as having taken less than eight minutes.

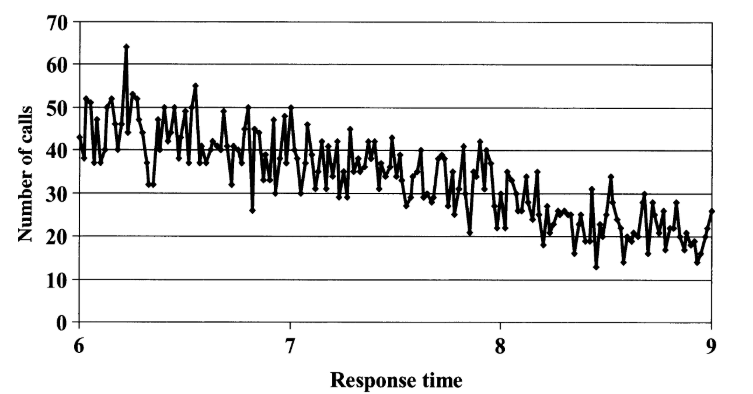

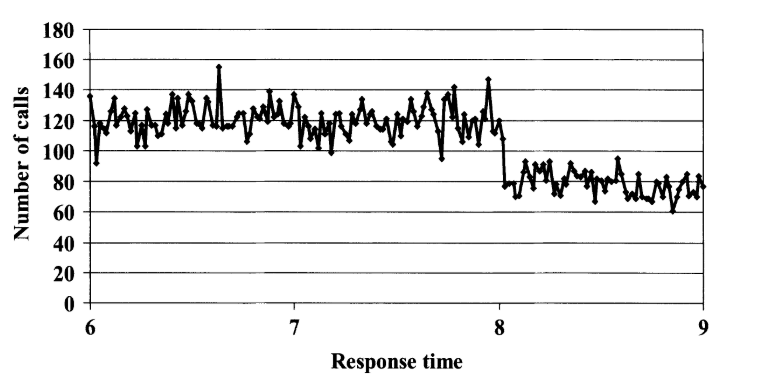

First, consider the recorded response-time data for a trust that exhibited an expected (‘uncorrected’) distribution of response times—a “noisy” decline in the number of responses with no obvious jump around the eight-minute threshold:

Next, consider data from two other trusts that exhibit what appear to be curious drops in reported response times at the 8-minute threshold:

The drop in reported response times is obviously more marked in the bottom figure, but also present in the first of these two figures. Clearly, something suspicious occurred with the reporting for these two trusts. As with sumo wrestlers, the putative setting of a harmless rule induced perverse behavior among the targeted group of Homo sapiens. In the case of England’s emergency ambulance services, it appears that some of the ambulance trusts chose to disingenuously fudge their reported Category A response times.

New York City’s Taxi Cab Drivers

Camerer et al. (1997) clued into the fact that taxi cab drivers are an ideal population to study for unexpected labor market behavior because the structure of the taxi cab market (at least, New York City’s (NYC’s) market in the late 1980s and early 1990s) enabled drivers to choose how many hours to drive during a given shift. As a result, drivers faced wages that fluctuated daily due to “demand shocks” caused by weather, subway breakdowns, day-of-the-week effects (e.g., Mondays may generally be busier than Tuesdays each week), holidays, conventions, etc. Although rates per mile are set by law, on busy days, drivers may have spent less time searching for customers and thus, all else equal, earned a higher hourly wage. These hourly wages are transitory. They tend to be correlated within a given day and uncorrelated across different days. In other words, if today is a busy day for a driver, she can earn a relatively high hourly wage. But if the very next day is slow, then the driver will earn a relatively low hourly wage.

Camerer et al. compiled different samples of NYC taxi drivers over three different time periods: (1) from October 29th to November 5th, 1990, consisting of over 1000 trip sheets filled out by roughly 500 different drivers (henceforth the TLC1 sample), (2) from November 1st to November 3rd, 1988, consisting of over 700 trip sheets filled out by the same number of drivers (henceforth the TLC2 sample), and (3) during the spring of 1994, consisting of roughly 70 trip sheets filled out by 13 different drivers (henceforth the TRIP sample). For each sample, Camerer et al. divided drivers into low- and high-experience subsamples.

Generally speaking, the authors find that drivers (particularly inexperienced ones) made labor supply decisions “one day at a time” (i.e., framed narrowly) rather than inter-temporally substituting their labor and leisure hours across multiple days (i.e., framed broadly) in response to temporary hourly wage changes (as you’ve probably guessed already, Homo economicus drivers frame broadly). The typical (Homo sapiens) driver set a loose daily income target (which served as the driver’s reference point) and quit working once she reached that target (which resulted in a negative relationship between the number of hours she chose to work and the driver’s daily hourly wage rate). In other words, as the driver’s hourly wage rose, she chose to drive fewer hours—a perverse outcome in a rational-choice model of any type of worker’s behavior. As Camerer et al. point out, the driver’s reference point established a daily mental account and also suggests loss-averting behavior in the sense that, on a slow day, a driver chose to work more hours to reach the reference point, thus avoiding the “loss” that comes with under-performing on the job.

Specifically, the authors find that low-experienced drivers exhibit negative responses to wage increases in each sample, but the responses are statistically significant only in the TRIP sample and marginally significant in the TLC2 sample. High-experienced drivers exhibit a negative response solely in the TLC1 sample. Therefore, Camerer et al. find some evidence of reference dependency, mental accounting, and loss aversion among NYC’s famed taxi drivers.

Savings Plans for the Time-Inconsistent

Homo sapiens who are time inconsistent when it comes to saving income for future consumption are prone to save too little now for what they later realize they needed in order to maintain their standard of living. In response, two types of “tailored savings plans” have been developed over time, targeting segments of the population with historically low personal savings rates. One plan—Prize-Linked Savings Accounts (PLSAs)—encourages people to increase their savings rates by adding a lottery component to what is an otherwise traditional savings account at a participating bank (Morton, 2015). Depositors’ accounts are automatically entered into periodic drawings based upon their account balances during a given period. Depositors then have a chance to win prizes, which are funded through the interest that accrues across the pool of PLSAs held at the bank.

As Morton points out, although they are relatively new in the US, PLSAs have a long history internationally. The first known program was created in the United Kingdom (UK) in 1694 as a way to pay off war debt. PLSAs are currently offered in 22 countries, including Germany, Indonesia, Japan, and Sweden. Because of Americans’ relatively low personal savings rates, and, as pointed out in Section 1, Homo sapiens’ general propensity to overweight improbable events (and thus, to accept gambles), PLSAs could potentially help raise savings rates in the US.

The US personal savings rate hit a high of 17% of disposable personal income in 1975, declining to roughly 2% by 2005, before rebounding to roughly 5% by 2014 (Morton, 2015). An estimated 60% of Americans had less than $1,000 in personal savings in 2018 (Huddleston, 2019). And yet, in 2019 an estimated 44% of American adults visited a casino (American Gaming Association, 2019). Hence, it seems that statistics also point to the potential role that PLSAs can play in nudging Homo sapiens to save more of their personal income.

One motivation behind the establishment of PLSAs is that Homo sapiens suffer from time-inconsistency when it comes to committing to saving for their futures. For some prospective savers, this time-inconsistency problem manifests itself as procrastination in opening up a savings account. For others, saving for the future is not considered imperative when juxtaposed against the need to cover current expenses.

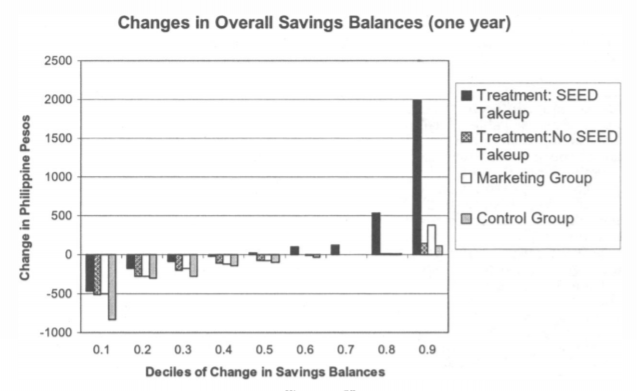

A second type of tailored savings plan—Commitment Savings Accounts (CSAs)—involves a prospective saver, or client, specifying a personal savings goal upfront which can be either date-based (e.g., saving for a birthday or wedding) or amount-based (e.g., saving for a new roof). The client decides for himself what the goal will be and the extent to which his access to the account’s deposits will be restricted until the goal is reached. The CSA earns the same rate of interest as a normal bank account.

To test the efficacy of a CSA in helping clients overcome their time-inconsistent savings decisions, Ashraf et al. (2006) conducted a field experiment with over 1,700 existing and former clients of Green Bank of Caraga, a rural bank in the Philippines. The authors first conducted a survey of each client to determine the extent of his or her time-inconsistency problem (i.e., to determine whether the client is an exponential time discounter (which, as we learned in Chapter 3, describes Homo economicus), a hyperbolic time discounter (which, as we learned in Chapter 4, describes many a Homo sapiens), or perhaps an inverted hyperbolic time discounter whose discount rate actually rises as the time delay for receiving a reward increases (recall that, under hyperbolic discounting, this rate falls as the time delay increases)). Next, half of 1,700 clients were randomly offered the opportunity to open a CSA, called a SEED account in this particular instance (Save, Earn, Enjoy Deposits)—the study’s treatment group. Of the remaining half of clients, half received no further contact (the study’s control group) and half were encouraged to save at a higher rate using one of the bank’s more traditional accounts (the study’s “marketing group”).

Of the subsample of clients in the treatment group, roughly 28% chose to open SEED accounts with the bank, the majority of which were date-based. After 12 months, just under 60% of the SEED accounts reached maturity (if date-based) or reached the threshold amount (if amount-based), and all but one client chose to open a new SEED account thereafter. Also, account balances for SEED account holders were markedly higher than for those clients in both the marketing and control groups. Further, women identified as hyperbolic discounters prone to time-inconsistent savings behavior (and thus, who presumably have stronger preferences for the SEED account’s commitment mechanism) were significantly more likely to open a SEED account. Preferences for the SEED account among time-inconsistent men were not as strong.

The figure below provides evidence of the SEED account’s effectiveness in inducing higher savings balances among those clients in the experiment’s treatment group who chose to open an account. Compared with clients in the control and marketing groups, as well as those in the treatment group who chose not to open a SEED account (Treatment: No SEED take-up), clients in the treatment group who opened a SEED account (Treatment: SEED take-up) grew larger savings balances after one year, especially among those clients with the largest balances (i.e., from the 0.6 to 0.9 decile groupings). Among those clients who suffered losses in their savings balances by year’s end, the losses suffered by the Treatment: SEED take-up clients were the smallest (as depicted for the 0.1 to 0.5 decile groupings).

As the results of this study suggest, tailored savings plans such as SEED appear to have potential for taking the “in” out of Homo sapiens’ time-“in”consistent tendencies when it comes to saving for the future.

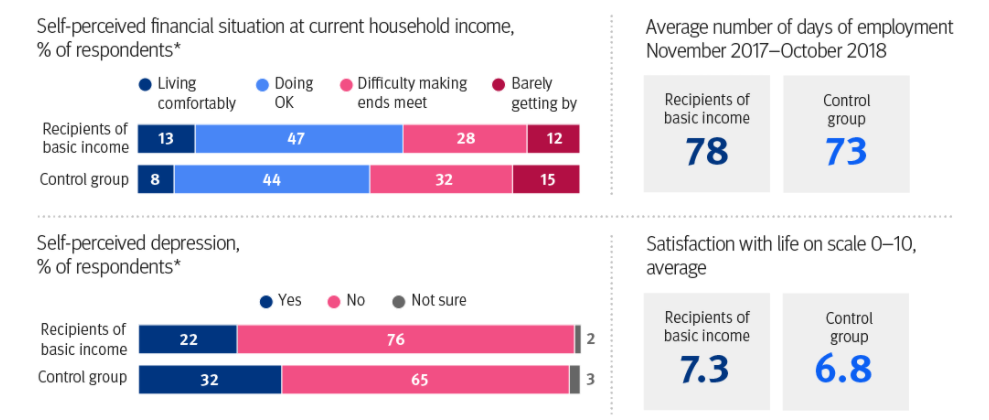

The Finnish Basic Income Experiment

Most nations provide some form of public social expenditure (PSE) to assist lower-income and otherwise marginalized citizens in meeting their basic needs over time. For example, among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, the nations of France, Belgium, Finland, Denmark, Italy, Austria, Sweden, Germany, and Norway devote at least 25% of their Gross Domestic Products (GDPs) to PSE (OECD, 2019). PSE includes cash benefits, expenditures on health and social services, public pension payments, and unemployment and incapacity benefits.

In 2017, the Finnish government conducted a two-year field experiment to learn if providing a basic income in lieu of PSE might boost employment and well-being among recipients more effectively than its traditional PSE programs (Kangas et al., 2019). In the experiment, a treatment group of 2,000 randomly selected unemployed persons between the ages of 25 and 58 received a monthly payment of €560 unconditionally and without means testing. The €560 monthly payment corresponded to the monthly net amount of the basic unemployment allowance and labor-market subsidy provided by Kela (the Social Insurance Institution of Finland). To study the effects of this basic-income program, the employment and well-being impacts experienced by the treatment group were compared against a control group comprised of 173,000 individuals who were not selected to participate in the experiment.

As the figure below shows, results for the first year of the program indicate that members of the treatment group on average experienced a (statistically insignificant) five-day increase in employment relative to members of the control group (Kela, 2020). Further, on a 10-point life-satisfaction scale, treatment group members reported a (statistically significant) 0.5-point gain.

As Kela (2020) points out, although the employment increase was relatively small overall, for families with children who received a basic income, employment rates improved more significantly during both years of the experiment. In general, members of the treatment group were more satisfied with their lives and experienced less mental strain, depression, sadness, and loneliness. They also reported a more positive perception of their cognitive abilities (i.e. memory, learning, and ability to concentrate), and perceived their financial situations as being more manageable.

These results beg an important question when it comes to implementation of new and innovative PSE programs: In the absence of tangible results, such as changes in employment rates, are the intangible benefits experienced by participating Homo sapiens worth the social investment?

Microfinance

One of the more innovative approaches to financing small businesses in lower-income countries is known as microfinance (Banerjee, 2013; Mia et al., 2017). Bangladeshi social entrepreneur and 2006 Nobel Prize winner Mohammad Yunus is credited as being the progenitor of microfinance because of a project he initiated in 1976, providing small business loans to small groups of poor residents in rural Bangladeshi villages. The project subsequently led to the founding of Grameen Bank in 1983, whose guiding principle is that small, well-targeted loans are better at alleviating poverty than donor aid.

The basic idea behind microfinance is simple. Because traditional lending requirements in the banking industry rely on borrowers pledging significant collateral to protect the interests of the lender, and because the risk of the borrower defaulting on a bank loan is often large and potentially costly, bank loans are generally considered off-limits to poorer entrepreneurs. Microfinance solves this loan-inaccessibility problem by lending to groups of entrepreneurs who essentially form cooperatives to advance collective business interests and take collective responsibility for loan repayment. The pooling of risk within the group lowers the chance of default on a loan and helps ensure that the loan will be profitable for both the borrower and the lender—a classic “win-win” solution, at least for Homo economicus borrowers and lenders.

But what about Homo sapiens? Although evidence suggests that microfinance has typically been a win for Homo sapiens lenders in terms of high rates of loan repayment (and therefore, low default rates) (Banerjee, 2013; Mia et al., 2017), the proverbial jury is still out regarding the extent to which microfinance has been a win for Homo sapiens borrowers. In an extensive field experiment, Banerjee et al. (2015) surveyed a large sample of residents located in 50 randomly selected poor neighborhoods in Hyderabad, India where branches of the microfinance firm Spandana and, later, other firms, had recently been established.[17] The authors surveyed the members of their sample three separate times—in 2005, 2007, and 2009 (i.e., before, during, and after the opening of the Spandana branches).[18]

The authors found that borrowers used microfinance loans to purchase durable goods for their new or existing businesses that had hitherto been unaffordable without the loan money. The typical borrower repaid the loan by reducing consumption of everyday “temptation goods” and working longer hours. No evidence was found of the loans ultimately helping to lift borrowers out of poverty in terms of improved health, education, and empowerment. If the loans helped anyone, it was the relatively larger, already-established businesses with relatively high pre-existing profit levels. Less than 40% of eligible, or “likely borrowers” availed themselves of the microfinance loans even though they continued to borrow from other informal sources.

The evidence for micro-financed loans on the profitability of solely new businesses is likewise bleak. The authors find that new businesses between roughly the 35th and 65th percentiles of profitability have statistically significant lower profits in the neighborhoods where microfinance loans became available. Nevertheless, Banerjee et al. (2015) report that this overall result shields divergent effects across industry types. In particular, new food businesses (tea/coffee stands, food vendors, small grocery stores, and small agriculture) that availed themselves of micro-financed loans on average experienced an 8.5% bump in profitability relative to new food businesses that established themselves in neighborhoods without access to microfinance loans. In contrast, new rickshaw/driving businesses backed by microfinance loans experienced a 5.4% decline in profitability relative to new rickshaw/driving businesses that established themselves in neighborhoods without access to microfinance loans.

In conclusion, Banerjee et al. are balanced in their assessment of the findings. They conclude that microfinance is indeed associated with some business creation—in the first year after obtaining microfinance, more new businesses are created, particularly by women. However, these marginally profitable businesses are generally smaller and less profitable than the average business in the neighborhood. Microfinance also leads to greater investment in existing businesses and an improvement in the profitability of the most profitable among those businesses. For other businesses, profits do not increase, and, on average, microfinance does not help these businesses expand in any significant way. Even after three years of having assumed a microfinance loan, there is no increase in the number of these businesses’ employees (i.e., business size) relative to businesses that did not assume loans.

Once again, the fickleness of Homo sapiens plays itself out in a market setting, this time in the neighborhoods of Hyderabad, India.

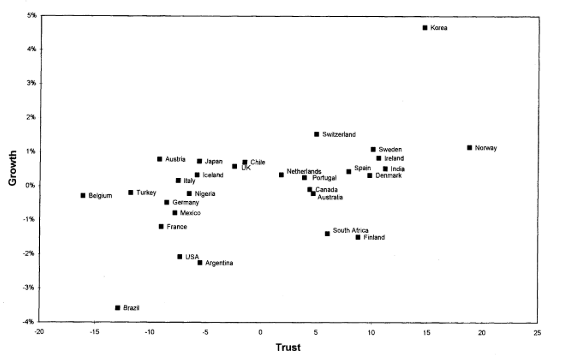

Trust as Social Capital

In Section 2 we investigated the trust game and the extent to which Homo sapiens participating in laboratory experiments express both their trust and trustworthiness. Knack and Keefer (1997) seek to answer the question, do societies comprised of more trusting and trustworthy individuals, all else equal, perform better on a macroeconomic scale? What is the relationship between interpersonal trust and norms of civic cooperation (i.e., social capital) on the one hand, and economic performance on the other?[19]

As the authors point out, conventional wisdom suggests that economic activities requiring agents to rely upon the future actions of others (e.g., transactions involving goods and services that are provided in exchange for future payment; employment contracts in which managers rely on employees to accomplish tasks that are difficult to monitor; or investments and savings decisions that rely on assurances by governmental agencies or banks that assets will not be appropriated) are accomplished at lower cost in higher-trust societies. Individuals in higher-trust societies spend less time and money protecting themselves from being exploited in economic transactions. Written contracts are less likely to be needed, and when needed, they are not required to specify every possible contingency. Litigation may be less frequent. Individuals in high-trust societies are also likely to divert fewer resources to protecting themselves from unlawful violations of their property rights (e.g., through bribes or private-security services and equipment). Further, high trust can encourage innovation. If entrepreneurs are required to devote less time to monitoring possible malfeasance committed by partners, employees, and suppliers, then they have more time to devote to innovation in new products or processes.

For their measures of trust and civic norms, Knack and Keefer utilize The World Values Survey, which contains survey data on thousands of respondents from roughly 30 different market economies worldwide. The survey question used to assess the level of trust in a society is this:

“Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?”

Based upon survey participants’ responses, the authors created a trust indicator variable (TRUST) equal to the percentage of respondents in each nation replying that most people can be trusted. The extent of civic norms present in a given society is gleaned from responses to questions about whether each of the following behaviors can always be justified, never be justified, or something in between:

- “claiming government benefits which you are not entitled to”

- “avoiding paying a fare on public transport”

- “cheating on taxes if you have the chance”

- “keeping money that you have found”

- “failing to report damage you’ve done accidentally to a parked vehicle”

Respondents chose a number from one (never justifiable) to 10 (always justifiable). The authors summed values over the five items to create a scale (CIVIC) with a 50-point maximum score. They then measured the impact of TRUST and CIVIC on both national growth (in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)) and investment rates. To control for other determinants found in the literature on economic growth, Knack and Keefer included in their regression analysis the proportion of eligible students enrolled in secondary and primary schools in 1960 (positively related to growth), per capita GDP at the beginning of the study’s timeframe of analysis (negatively related to growth), and the price level of investment goods (also negatively related to growth).

According to the figure below, which shows a scatter plot of the relationship between the countries’ TRUST and economic growth rates, the relationship appears to be positive (i.e., if you were to draw a line through the scattered points that represents a likely trend, the trend line would have a positive slope).

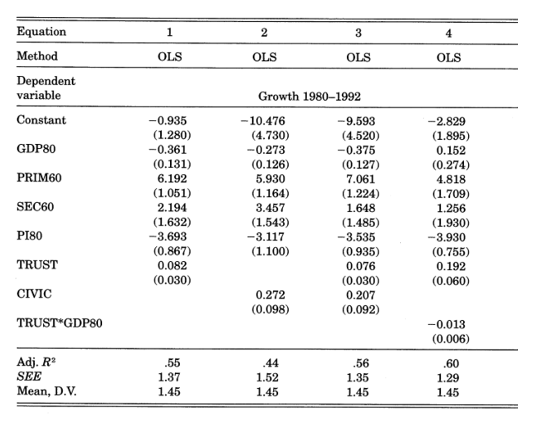

The table below presents the authors’ empirical results based upon different specifications for ordinary least squares (OLS) regression equations:

The social capital variables exhibit a strong and significant relationship to growth. For example, in Equation 1, the estimated coefficient for TRUST is positive (0.082) and statistically significant (due to its relatively low standard error of 0.030 in parenthesis). As Knack and Keefer explain, TRUST’s coefficient indicates that a ten-percentage-point increase in TRUST’s score is associated with an increase in economic growth of four-fifths of a percentage point. Similarly, according to CIVIC’s estimated coefficient, each four-point rise in the 50-point CIVIC scale in Equation 2 is associated with an increase in economic growth of more than one percentage point. When both social capital variables are entered together in Equation 3, their coefficient estimates drop slightly but remain statistically significant. Finally, the negative (and statistically significant) coefficient value on the interaction term TRUST*GDP80 indicates that the effect of TRUST on economic growth is lower for countries with higher initial per-capita GDP levels at the beginning of the timeframe of analysis, in 1980 (represented by variable GDP80).

Therefore, it seems that Knack and Keefer’s evidence of the extent to which trust and civic norms affect the welfare of a country supports the hypothesis that trust is indeed a form of social capital.

Reputational Effects

In Chapter 8, we learned of Fehr and Gächter’s (2000) finding that Reputational Effects among a group of repeatedly partnered players in a laboratory-conducted, finitely-repeated Public Good Game are capable of mitigating free-riding behavior among the players (i.e., contribution levels that are repeatedly too low to adequately fund the public good). Concern about one’s reputation among other players (for either strategic or non-strategic reasons) is a strong-enough incentive for players to voluntarily contribute at higher levels.

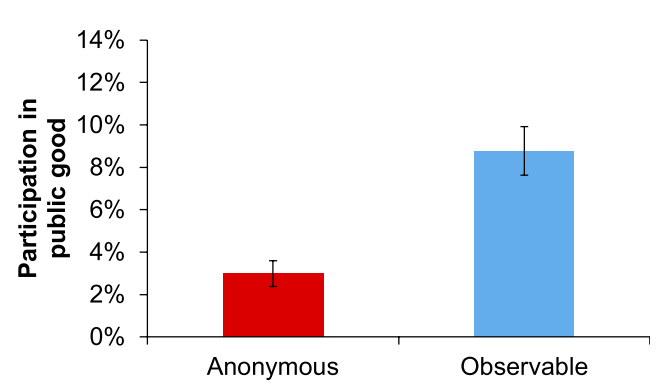

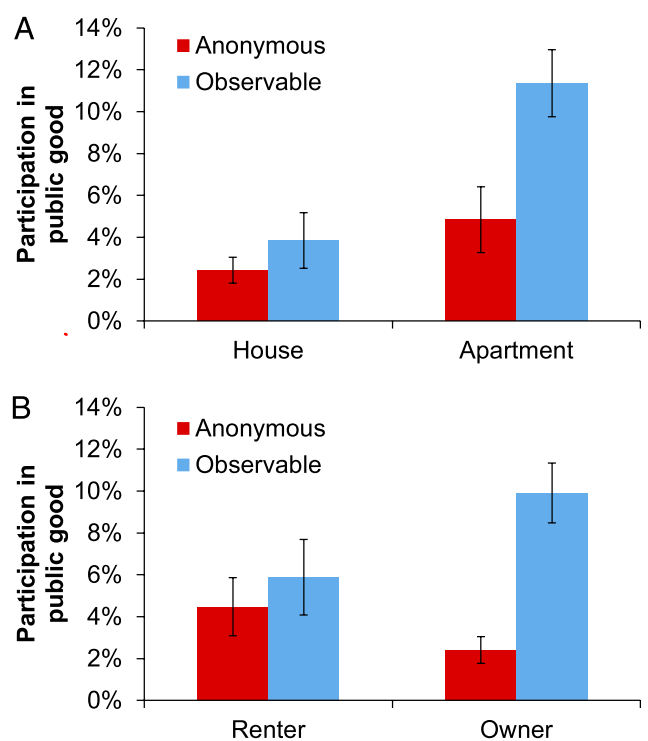

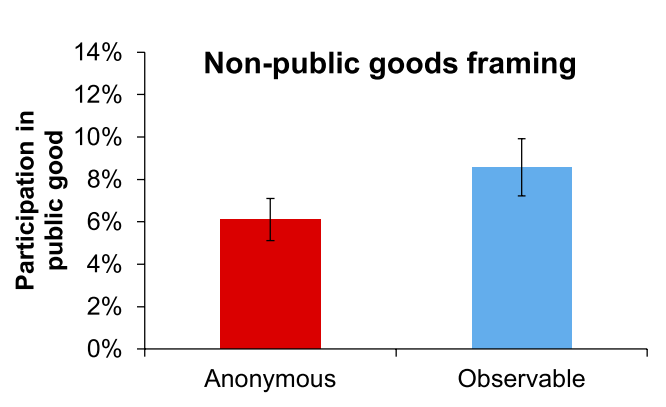

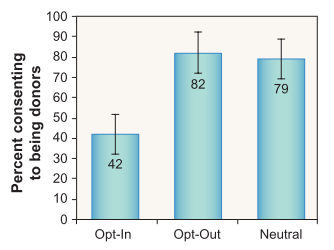

Curious about whether a Reputational Effect (or “indirect reciprocity”) is capable of promoting large-scale cooperation in real world settings, Yoeli et al. (2013) designed a field experiment involving over 2,400 customers of a California utility company, Pacific Gas and Electric Company, in order to study the customers’ levels of participation in a “demand-response program,” called SmartAC, designed to prevent electricity blackouts (before getting into the proverbial weeds of the experiment, convince yourself that participation in a prevention program like this indeed fits the definition of a public good).[20] The authors’ hypothesis is that the effects of indirect reciprocity are strong in a setting such as this.