2 Truth

At this point someone might raise an objection:

Objection: You have claimed that knowledge implies truth—in other words, in order to know something, that something must, in fact, be true. But this makes the definition entirely useless. If we have to know what’s true in order to figure out what we know, then why bother with any definition for “knowledge” in the first place? Why not just rest content with the truth?

This is a good question. It forces us to become clear about what we want in a definition. Sometimes we want to use definitions to help us sort things into categories. Consider, for example, the standards set forth by the American Kennel Association for figuring out when this or that animal is a member of this or that breed. In this case, we want the definition to act as a sorting mechanism to help us decide whether this or that thing should be called whatever it is we are defining. But other times, we simply want a definition to tell us in a more general way how the target concept relates to other concepts. This increases our understanding of the concepts, though may not decisively settle any disputes.

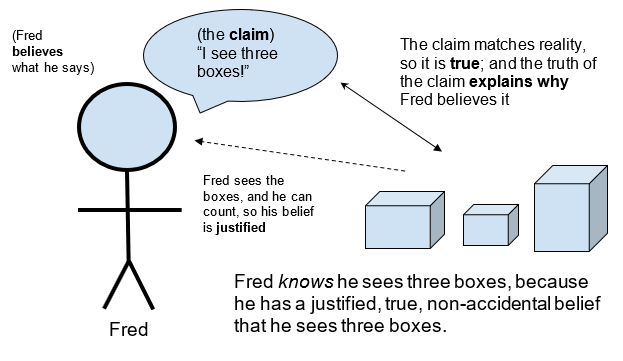

The JTB+ definition of knowledge is definitely the second sort of definition. We have seen that knowledge is related to belief, truth, justification, and explanation, though this has not brought us any closer to being able to assemble some sort of “litmus test” we can use to determine which of our beliefs should count as knowledge. The effort to assemble such a test has a long history in philosophy; it is the effort to refute skepticism. We will discuss that at length later on.

But let us pause over truth a bit longer. What is truth? This is the sort of question philosophy is famous for, and one might expect a very impressive and mysterious answer like “Truth is beauty” or “Truth is what releases us from ourselves” or something else. These are interesting claims to reflect on. But in fact, philosophers typically rely on a simple and straightforward meaning of truth. First, we need to ask again what sorts of things are true. Are we talking about people, concepts, neutrons, or what? Once again, it is propositions or sentences that we say are true or false. So what makes a proposition true? Here is the simple answer: a proposition is true if and only if it describes how things really are. When a proposition matches reality, the proposition is true. That’s it.

Objection: Once again, this seems like a useless answer. How do we know what reality is? And without knowing what reality is, how can we determine which propositions are true?

These are great questions, and they are at the foundation of epistemology. If we want knowledge, we want to know what’s true, or what reality is, and how we should go about discovering what reality is, and what we should do when we are not completely sure what’s true. That’s what this book is about.

Here is everything we have said so far summarized in cartoon form:

Media Attributions

- Figure 1.1 © Charlie Huenemann is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license