11 Problems with Phenomenalism

Many people reject phenomenalism for some strange and unconvincing reason. But there are also good lesser-known reasons for rejecting phenomenalism. I will sketch two of these reasons: the problem of necessary truths, and the problem of sense data.

The problem of necessary truths is the problem of how phenomenalism can account for our knowledge of truths that strike us as necessary truths. This is a bit tricky to explain. Some truths seem like just accidental truths about the world. Giraffes have long necks. The moa is, sadly, extinct. And here is some good news: there are currently more than 5,000 black rhinos, which is more than twice as many as there were in 1995. All of these truths, it seems, could have been otherwise. Giraffes could have evolved to have shorter necks, the moa could have survived, and black rhinos could be even more (or less) populous than they currently are. Call these truths that could have been otherwise contingent truths (“contingent” means that they depend on other facts for their truth).

Other truths in our experience seem more necessary and less contingent. Consider the claim that the earth is gravitationally attracted to the sun or that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. Are these claims true in exactly the same way that it happens to be true that giraffes have long necks and the moa is extinct and there are more black rhinos than before? Normally we think of laws of nature as more necessary and less changeable than other claims about the world. They describe what must happen, and not just what happens to have resulted. But what in our experience could make these truths more necessary?

The mere fact that we do not come across exceptions to the laws of nature does not show they are more necessary. We also never come across short-necked giraffes or existent moas or herds of a million black rhinos, but that does not show that there could not be such things. Indeed, it is hard to imagine the necessity of a truth being somehow apparent in our experience. Would it glow somehow or have a warning sticker on it telling us that this portion of our experience is non-negotiable?

A phenomenalist might try to answer this question by simply insisting that there are laws that govern our experiences, and these laws have some sort of greater authority or are somehow more fixed and less changeable than the contingent truths we experience. Perhaps the laws of nature are due to the program in the simulation or due to rules set down by God or a mad scientist. But if a phenomenalist insists on this, then they must appeal to facts that lie outside our experience: facts about the program, or God, or the mad scientist. There is nothing internal to our experience to show that the laws of nature are more necessary than any other accidental generalization we come across (like “all giraffes have long necks”). This suggests that one cannot be a “pure” phenomenalist and make sense of laws of nature. They have to reach outside their experiences in order to explain something they have found to be true inside their experience.

Alternatively, a phenomenalist might bravely deny that any general truths are more necessary than others. They may insist that “all giraffes have long necks” is just as necessary, or just as contingent, as “for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.” But the cost of making this denial is that it will ruin our efforts to explain natural phenomena. Normally, we try to explain things in nature on the basis of a relatively small set of fixed laws (like the laws discovered in physics and chemistry). Doing so, we think, gives us a deeper understanding of how nature works since it shows us why particular facts must happen in the way they do. If we deny that there are any laws of nature and instead say there are just truths about how things happen to be, it becomes ludicrously easy to explain anything. If someone asks us why apples fall to the ground or why giraffes have long necks or what makes gold more dense than copper, we can simply declare, “That’s how things are!” and call it a day. It would not make sense to dig any deeper to try to find the fixed features of nature that explain what we experience.

So, one problem with phenomenalism is that it is not clear how it will allow us to distinguish contingent truths from necessary truths. A second problem is that phenomenalism requires us to believe in some strange things that exist in a middle place between objects and us, namely perceptions or experiences. Other philosophers have called the perceptions “sense data.” They are the things I have put inside clouds in the diagrams. We have been presuming all along—indeed, even the GDD itself makes this assumption—that there is a difference between objects and our perceptions of objects, and that those perceptions could, in principle, exist without those objects causing them. But is this a good assumption? How confident should we be that sense data can exist on their own?

One must admit that sense data are weird things. There is no scientific evidence for their existence—they do not show up in brain scans, or under microscopes. But they are supposed to be the most obvious things in the world that even an extreme skeptic cannot doubt. Do they vanish into nothingness when they are not being experienced, and pop back into existence when we have experience? When I see a giraffe, then close my eyes, and then look again, have I experienced two different sense data or have I experienced the same sense datum twice? How can I be sure whether it is one or two sense data—or three or more? If you stand where I stood and look at the same thing, do you now enjoy the same sense datum I enjoyed a minute ago? Or are the sense data two identical copies? There are not good reasons for favoring one answer to these questions than any other. For being the most obvious things in the world, sense data are not very obvious after all!

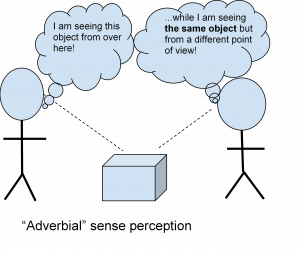

But is there any way we can understand our experience without using sense data? Yes, there is. Suppose we do away with sense data as intermediary objects existing between objects and us. We say instead that we are experiencing the objects directly. But of course your experience may not be exactly the same as my experience even though we are experiencing the very same object. But this difference, we shall say, is not due to you having one sense datum and my having another; it is instead due to you perceiving the object in one way and my perceiving the object in a different way. “Different ways of perceiving” are not sense data; that is to say, there are not different things standing between us and the objects we perceive. Rather, you and I are seeing the same thing, but in different ways. It is a difference between adverbs rather than a difference between nouns.

This might sound like we are merely playing with words, but in fact, this simple change in how we talk about our experiences makes phenomenalism impossible. The whole idea of phenomenalism is that we can separate our perceptions from the objects alleged to cause those perceptions and make do with just the perceptions themselves. But if there is no way to separate perceptions from those objects—if perceptions just are those objects, perceived in a certain way or from a particular point of view—then the perceptions cannot be separated from the objects, and phenomenalism does not even get off the ground. There is no gap between the observer and what is observed.

This way of understanding our perceptions avoids postulating sense data which (as we have seen) are weird things to postulate. It does postulate different ways of experiencing things, but that is well understood. You see an object from some position, under certain lighting conditions, while wearing sunglasses, and so on. This does not mean that the object you are experiencing is different from the object anyone else is experiencing; it means you are experiencing the same object as other people are experiencing, but under different conditions. This means the objects really do exist after all.

Media Attributions

- Figure 4.4 © Charlie Huenemann is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license