10 Knowledge of Appearances, or Phenomenalism

The skeptics who offer the GDD claim that, for all we know, everything we ever sense could be an illusion. One way to reply to these skeptics is to call their bluff. So what if everything is an illusion? We still have to deal with appearances. We still have to get up in the morning, do our exercises, go to work, deal with people, solve problems, pay taxes, and die. Does it really matter whether what we are experiencing is only a very thorough illusion? What practical difference would this make in our lives?

This response to the skeptic maintains that we can get all the knowledge we shall ever need through a careful study of appearances, and we should never have to insist that these appearances come from some “external” world (meaning, a world external to the appearances). The task, then, is to show that we really can get everything we need from mere appearances. The efforts to show this are sometimes called “empirical idealism” or “phenomenalism,” and such efforts have been made by George Berkeley (1685-1753), Ernst Mach (1838-1916), Bertrand Russell (1872-1970), and Rudolf Carnap (1891-1970), among others. We will sketch a similar effort in this section.

We can begin this project by thinking through what we would have to do if we wanted to create a very compelling virtual reality machine. With such a machine, you can strap on goggles or a helmet and be treated with the sights and sounds of another world—a Martian landscape, Middle Earth, ancient Rome, or whatever you like. But we want our VR machine to be much more thorough. We want not only sights and sounds, but smells and textures and tastes. We want to feel the ground beneath our feet, and we want to experience the difficulty of walking up steep hills. We want the world to be wide open so that no matter where we decide to turn or run or jump or crouch, the machine will respond with the appropriate set of images and features for us to experience. We want the real in our virtual to seem as real as our real in the real. (By the way, isn’t that an interesting sentence?)

Let’s think through what this requires by taking up a specific example. Let’s say I am in the VR of ancient Rome, and I am going to walk up to a statue and examine it from all angles. Obviously, the statue that I am looking at does not exist in the real world. In the VR, I am presented with images that show how a real statue would look from all possible angles. I walk around the sculpture, and I am presented with a series of images of the sculpture, smoothly transitioning from one to the next. I lay down on the ground, and I see an image of the statue from below. But, again, there is no statue—not really. All that exists is a very extensive set of images produced by the VR program. I experience three sets of images similar to one another but also different which together “suggest” that there is an object “out there” that corresponds to the sets of images I experience.

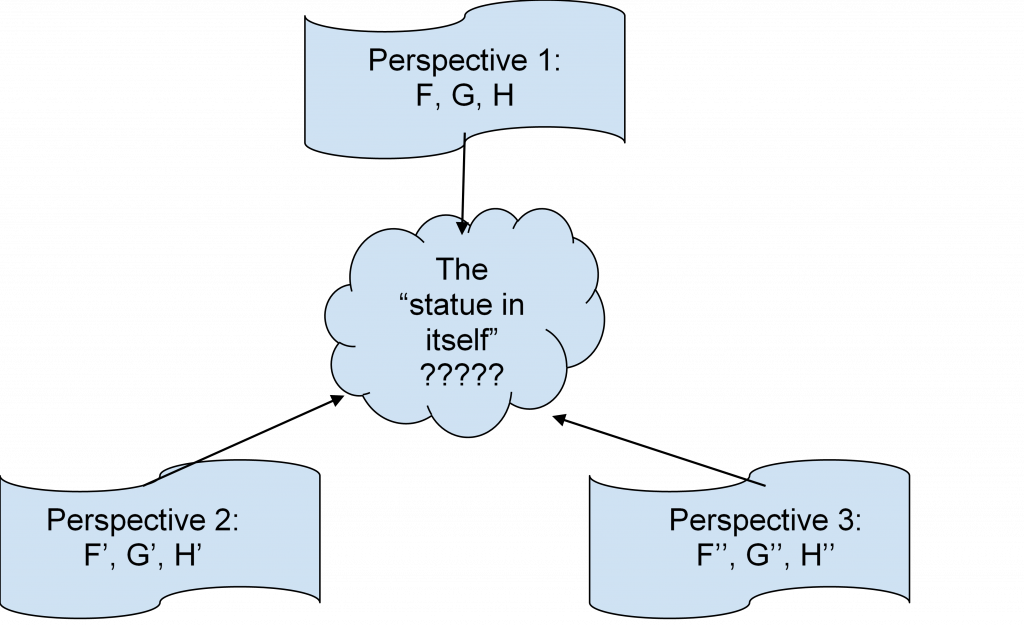

Of course, in a VR situation, there is no “statue in itself” except as a collection of images included in a number of “perspectives.” We pretend that there is a “statue in itself,” though we only see the images from one perspective or another. Image F is very similar to image F’, which is very similar to F’’, but they are all subtly different from one another in such a way to suggest the illusion that we are moving around a stable, fixed object (“the statue”) which does not really exist. Setting this up requires a lot of thought and a lot of coordination, though there is no reason to think it cannot be done. It just requires a lot of planning in how the images are constructed and the order in which they are viewed.

To make the sort of VR we are imagining, this sort of construction would have to take place for each and every virtual object and for all of the angles from which the virtual “object” could be seen. Similar sorts of programming would have to be done for every sound and smell and taste. Imagine having to program just how a virtual orange would taste after biting a virtual lemon as opposed to how it would taste just after brushing your virtual teeth! Imagine having to program just how the smell of some virtual old socks would change as you became used to the smell.

“Hold on,” I imagine someone thinking. “What do you mean by my ‘virtual’ teeth? Can’t I use my real teeth?” No, you can’t. For in the VR we are imagining, we will have to present you with images of your (virtual) feet if you look down at them, images of your (virtual) eyes if you look into a (virtual) mirror. We shall even have to present you with images of your (virtual) brain if you decide to do brain surgery on yourself. Basically, all of the sensory images you experience—indeed, all sensations whatsoever, whether of yourself or other things—will have to be generated from the VR programming. Plugging into this VR system means leaving the so-called real world behind and experiencing only the sights, sounds, tastes, textures, smells, and other features of the virtual world. And that will include the sensations of your own body.

I keep pointing out that the ‘objects’ in the virtual world don’t really exist. That is to say, they do not exist in the normal way we take ordinary objects in our ordinary reality to exist. But there may be another sense in which they do exist: they exist as complicated structures within the VR program. For example, I might say that the statue’s left elbow just is the set of F, F’, and F’’ that relate to one another in the way described above. The same, of course, for the head and for the left knee. What groups them together as images of the left elbow, or the left knee, or the head, is that the images share a certain structure, or have great similarities to one another, and the images change smoothly from one to another according to general rules that hold for any observer who is “walking around the statue” in the same way we are.

Hopefully, we have spent enough time thinking through this example to have a solid sense of what is being proposed under the names “empirical idealism” or “phenomenalism.” These philosophical views assert that our real world is in fact like the virtual reality we have been thinking about. There are no material objects existing “out there” for us to experience. There are only the sensations we experience, organized in the way a very advanced VR would be programmed so as to generate the appearance of a world of objects. Really, when we refer to the Eiffel Tower or the pyramids of Egypt, we are referring to all of the perceptions one might experience when one undergoes the actions that initiate certain sequences of perceptions we associate with “experiencing the Eiffel Tower” or “experiencing the pyramids.” Only experiences exist. And this includes the experiences of our own bodies for the reasons given above. We experience our bodies through our senses, or through images in mirrors or recordings, but these also are just experiences and not different in kind from the statues and towers and pyramids we can experience.

Normally (when we are not doing philosophy), we believe something like this: there exists a world of objects which cause us to have perceptions of those objects. A phenomenalist drops out the world of objects and inserts in its place some other cause, or perhaps just a question mark, and keeps everything else—all our perceptions—exactly as it was before.

Objection: What is the point of working though all of these construction details if, in the end, all our experience remains unchanged?

But remember why we started this section in the first place. We wanted to find some way to answer the skeptic. The skeptic was asking how we could be sure we were in a real world instead of some sort of virtual reality (caused by demons, mad scientists, God, etc.). We called the skeptic’s bluff. That is, our effort has been to show that our world could very well be virtual in just the way the skeptic seems worried about, and it really would not matter for all of our intents and purposes. The GDD need not bother us.

In calling the skeptic’s bluff, we gain some advantages. First, all our knowledge is based on things we immediately experience—the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, textures, and perceptions of daily life. We could be wrong about what those experiences are experiences of, but we cannot be wrong about the fact that we have those experiences. And if we base the rest of our knowledge just on those experiences, we will have placed all our knowledge on a secure foundation, and we can tell the skeptic to run along and pester somebody else.

There are some interesting further questions we might consider:

- If only experiences exist, how am I ever wrong about anything?

- How can I be sure other people (meaning, other conscious minds) exist?

- What causes my experiences? Who or what organizes my perceptions?

We will briefly consider each of these questions in turn. But first I will offer a hint to help you in thinking through the answers to them for yourself. For the phenomenalist, all knowledge is rooted in experience. So the answer to any question will be a question about what our experience is when we ordinarily try to answer those questions. If you want to know how a phenomenalist answers a question, ask yourself what experiences you have when you try to answer those questions in a more commonsensical context.

How am I ever wrong about anything? Well, what happens ordinarily when we have the unfortunate experience of being wrong about something? Perhaps I think that 5 x 7 = 42; someone takes me slowly through the calculation and shows me otherwise. Perhaps I think India is larger than Canada; someone grabs a globe and asks me to study it more closely. Perhaps I think Woodrow Wilson is president; someone shows me a recent newspaper that suggests otherwise. Generally, when we learn we are wrong, we can describe the experience of being shown wrong, and once we have the experience of being shown wrong, we have all the phenomenalist requires to answer the question.

This means that truth means something slightly different for the phenomenalist than it does for non-phenomenalists. Non-phenomenalists think that we are wrong when what we think or say does not match how things really are (where “really are” means outside of one’s experience). But for the phenomenalist, being wrong means saying or thinking something that does not match what the rest of experience shows. When someone is wrong, their belief is not consistent with a relevant set of experiences (like doing a calculation carefully, studying a globe, or reading a newspaper). This might be seen as a point in the phenomenalist’s favor, actually, since that does seem to be what we do when we try to determine whether we are right or wrong: we look to other experiences and see whether our beliefs are consistent with them.

How can I be sure other conscious minds exist? Well, once again, consider what experiences suggest to us that other conscious minds exist. To the extent that I am sure of the existence of other minds, it is because of what other people seem to say or do. On the basis of my interactions with other people, I come to believe they have their own thoughts and feelings, and that they have experiences much like my own. If someone presses the objection, asserting that, for all I know, other people could be characters generated by a computer program, or non-playable characters, I may have to admit that this could be the case. I really cannot be sure at a very fundamental level. But who can? This again seems to be a point in the phenomenalist’s favor. We should be skeptical of any answer to a skeptic that promises too much, or promises knowledge that we don’t ordinarily take ourselves to have.

What causes my experience? This question requires special treatment if we think that whatever causes experience has to be something that does not show up in our experience. If we think this, then obviously we cannot examine our ordinary experience to show us how we ordinarily go about answering the question. At first glance, it appears that a phenomenalist really has no compelling answer to offer. Our experience could be coming from a world of spatiotemporal, material objects, or it could be coming from a demon, or a mad scientist, or God, or some psychedelic eggplant with telepathic powers. There is no way of knowing since, for the phenomenalist, all our knowledge is based upon experience, and obviously, we do not have any experience of anything outside of experience.

But on further thought, we may notice that the phenomenalist does not need to answer this question. The basis of knowledge, for the phenomenalist, is experience, or data, or “what is given.” What we know we know because it is either present in experience or constructed from experience. If someone asks us about things that are totally outside of experience, we may legitimately respond, “You are asking about things of which no knowledge is possible.” And no one should expect us to do the impossible! So the question “What causes our experience?” is something like a meaningless question, like asking whether triangles are married or if the color green is for sale.

So phenomenalism has a lot going for it as an answer to the skeptic. One might even praise it as the most responsible approach to knowledge someone could take, as it forces us to make sure everything we think we know is connected in clear ways to what we experience and cautions us against believing in anything beyond what experience shows. Yet in my experience, very few people wish to be phenomenalists. In a class of thirty students, I may have one or two who are interested in adopting the view. Strangely, it is because people really like the idea of there being a material world even if it lies outside of any possible experience. For most people, it is not enough to believe in the experience of touching a statue and feeling its hardness; there must also really be a statue in addition to whatever I can possibly experience of the statue. I call this “strange” because it is strange that people should feel so confident about an object that they themselves will admit—at least, after a bit of philosophical discussion—is an object that they can never possibly experience (“the statue in itself”).

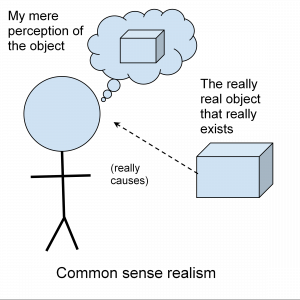

Let us explore the strangeness of this confidence a bit further. Ordinarily, before we begin to philosophize, we think that there are objects in the world, and these objects somehow cause our experiences of those objects. If we are asked why we believe the objects cause our experience, our general feeling is something along the lines of, “What, are you crazy? These experiences must come from somewhere! My experiences are experiences of objects.” This attitude is what we may call “common sense realism.”

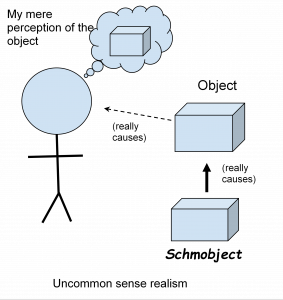

But now suppose I extend common sense realism a bit further. I say, “Well, surely you don’t think that is the end of the matter, do you? For these objects must also come from somewhere just as the experiences must come from somewhere. And just as experiences come from objects, I tell you now that objects must come from schmobjects.”

According to this new view, which we may call “uncommon sense realism,” it is not enough to merely claim that objects cause our perceptions. We must explain what causes those objects. The cause of those objects is what we should call schmobjects, I say. Schmobjects cause objects in exactly the way that objects cause our perceptions of objects.

If you ask me why I believe in schmobjects in addition to objects, I shall reply, “What, are you crazy? These objects must come from somewhere! Objects are the effects of schmobjects.” You can hardly accuse me of being less rational than the person who made a similar claim about experiences coming from objects.

But wait, there’s more. Schmobjects can’t just exist by themselves, can they? They must be caused by flobjects. And flobjects are caused by globjects. And globjects are …

And off we go in an endless regress to crazyland. We should cut off this endless regress somewhere, don’t you think? And wouldn’t it be reasonable to cut it off at the point where our experience ends and not go on to assert the existence of things of which we have no experience? That would leave us with phenomenalism, wouldn’t it?

But strangely, most people seem to like to assert the existence of objects and don’t feel arbitrary at all in denying the existence of schmobjects. What can I say? People are weird.

Media Attributions

- Figure 4.1 © Charlie Huenemann is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 4.2 © Charlie Huenemann is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 4.3 © Charlie Huenemann is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license