15 Internalism and Externalism

At this point, it is important to distinguish two different general approaches to questions in epistemology: internalism and externalism. The difference is between figuring out knowledge “from the inside” (internalism) and figuring out knowledge “from the outside” (externalism). An internalist approach works with the resources each of us has as knowing beings—what we can sense, what we already believe, and what we can reasonably conclude from those things. An externalist approach instead takes a broader view of knowing beings, considering not just what is “inside” them but also their circumstances and their patterns of success in the past. It would not be far off to say that internalism is epistemology from a first-person perspective while externalism is epistemology from a third-person perspective.

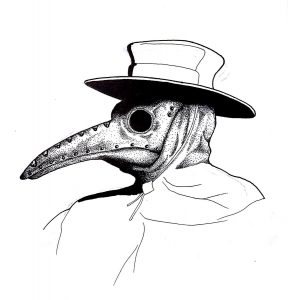

An analogy might be helpful. Suppose you are asked to rate the performance of a certain plague doctor in 14th-century Florence. You might first ask by what criteria you are supposed to rate this doctor. Should you rate the performance according to the set standards of 14th-century medicine? If so, then perhaps the doctor did a great job; he rubbed onions and dead pigeons on the bodies of the plague victims and gave them vinegar to drink just as he was supposed to. This would be an internalist rating, or a rating based on more local information. But if you are supposed to rate the doctor according to today’s medical practices, you will have to conclude that his performance was, well, not so great. This would be an externalist rating since the standards come from factors far beyond the plague doctor’s own beliefs and experiences. There is something valuable to be learned from each approach, though they are very different from one another and call upon different sets of facts.

So how does this analogy apply to epistemology? In this way. Sometimes we may find it important to understand the individual’s local information: their own experience, reason, and beliefs and the processes by which they come to know what they think they know (internalism). Other times we may want to know, in fact, whether those processes really do deliver knowledge according to what the rest of us on the outside think we know (externalism). We might examine the individual’s methods for forming beliefs in relation to what we know about their situation and what we know about the reliability of those methods.

Many philosophers have insisted that internalism best captures the meaning of “knowledge,” and others have insisted that externalism best captures the meaning of “knowledge.” But I see no reason to make any such insistence any more than I see any need to insist that one way of evaluating 14th-century Florentine plague doctors is better than the other. Each way gets something right depending on what we are interested in.

Over the last couple of chapters we have seen how difficult it is to offer good internalist answers to the skeptic. What this means is that it is hard for us to find within ourselves reasons or experiences that show that what the skeptic says is false. Phenomenalism is one route a person could take, trying to base all of their beliefs on sense data. Or they could follow Descartes’s route and establish God’s existence and God’s good nature so that they can trust whatever seems to them clearly and distinctly to be true. These answers, as we have seen, only go so far in answering the skeptic.

But what about an externalist answer to the skeptic? Here there is much greater promise as an externalist can call upon a broader circumstance that reaches beyond our own experiences as individuals. Most significantly, an externalist can draw upon the circumstance that, as a matter of fact, we are usually not being radically deceived. To see how this works, suppose you are sitting in the library wondering if you are in a GDD scenario. An externalist comes along and asks what you are doing. You answer that you are undergoing a skeptical crisis, and the externalist says, “Nope, clearly you are not in a GDD situation. For you are in the library, sitting in a chair. If that is what it seems to you that you are doing, then you are right, my friend, for you really are doing it. Your beliefs are true, and your senses are reliable, so you have knowledge, and the GDD is refuted.” We can then imagine the externalist sauntering away, whistling a jolly tune.

Now it might seem to you that the externalist is missing the point. What you want to know is whether you really are sitting in a chair in the library. But the externalist will say that, yes, really, you are; it is a fact. “But how do you know?” you ask. The dialogue continues as follows:

Externalist: I know this because my eyes are working well (I visited the optometrist just yesterday), and I know what chairs and libraries are (I just watched a stimulating educational video on the topic), and I see you sitting here in a chair in the library.

You: Well, you think you do! How do you know you’re not being deceived by an evil demon or a mad scientist?

Externalist: What an odd question! Do you see me standing here talking to you?

You: Yes, I think I do.

Externalist: Do you see any demons fluttering about or wires coming out of my head or mad scientists around me?

You: No.

Externalist: Do we have good evidence for thinking people are routinely deceived by demons or mad scientists? Is this something you see reported by credible media agencies?

You: No.

Externalist: Do you regard it as a sound epistemic practice to go around believing in stuff that you do not experience and is not reported to you by any credible source?

You: No.

Externalist: Then why on earth are you doubting whether we are here having this conversation?

In this riveting dialogue, the externalist is changing frameworks on you. Your doubt about being in the GDD scenario was arising from an internalist perspective, and the answer being offered by the externalist is coming (rather predictably) from an externalist perspective. From that perspective, the GDD seems sort of silly.

Maybe you are still not convinced? Well, the aim of this chapter is to show the merits of externalist approaches in epistemology.

Media Attributions

- Figure 5.1 © Cuddly Beast is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license