17 Epistemology Naturalized

The American philosopher W. V. Quine (1908-2000) offered an externalist epistemology in which our understanding of knowledge is based on a scientific understanding of our situation. Through science we are learning more and more about the natural world, about human psychology, and about the ways in which humans form beliefs about the world. Our scientific knowledge is not absolutely certain, of course—it may be that next week we learn that our current scientific theories are wrong in many fundamental ways. But contemporary science does represent the best we have been able to do so far (or let us assume this is so; more discussion of this will come in the next chapter). Is it not natural to use what we have learned about human psychology and the world in order to understand what it takes for human beings to know something?

This is what it means to naturalize epistemology: it is to see epistemology as continuous with our science of the natural world, including the humans in it. When we ask, “How do we know that we have hands?” we should not seek some ground-shaking answer that will cause skeptics to run for cover. We should take the question seriously in the way that a scientist would. How do we know that we have hands? Well, our nerves are sending signals to our brains that indicate to us what our hands are doing and where they are, light waves are bouncing off our hands and entering our eyes, and signals are sent from our eyes to our brains where they are processed in such a way as to give us the belief that we have hands. Normally, our nerve signals are extremely reliable when it comes to telling us such things. If we doubt this, we could run an experiment with many people, some with hands and some without, and determine just how reliable our nerve-signal-processing functions are. In the end, we will find that it is virtually certain that those of us who think we have hands do in fact have hands.

Objection: This so-called justification of our knowledge is circular. (Calling it “circular” is to say that it assumes what it is supposed to prove.) After all, if I am really doubting whether I have hands, then I am also doubting whether there are other people, and whether there is any scientific knowledge, and whether careful so-called scientific experiments really show anything about reality. But the externalist is supposing that we do have all of this scientific knowledge and then uses that knowledge in order to justify that parts of that big system of knowledge—specifically, the parts that describe our nerve signals and brain functions—are trustworthy. The externalist is assuming our knowledge of the external world in order to justify the claim that we do have knowledge of the external world. How convincing is that supposed to be?

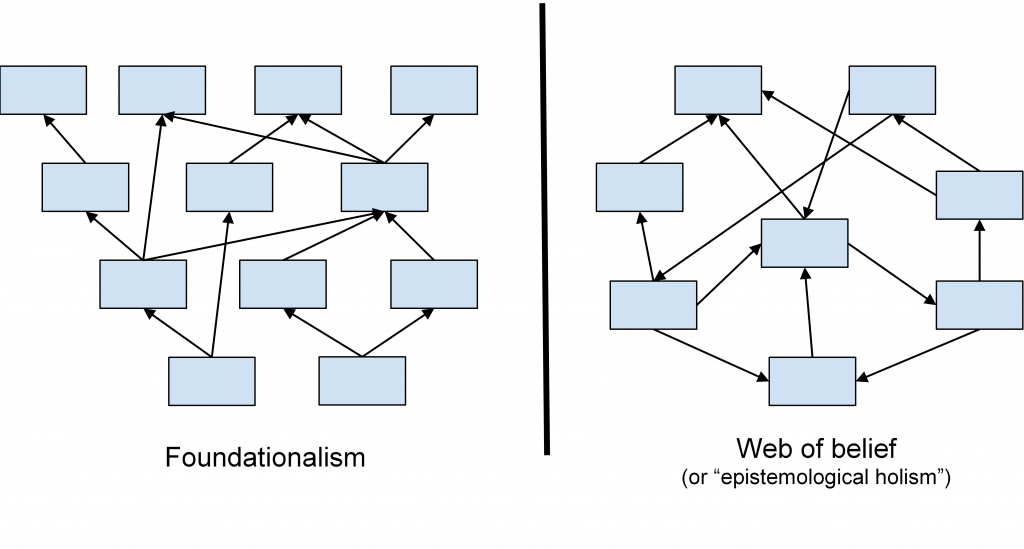

Quine responded to this objection of circularity. His response was that the objection arises from a mistaken view about how knowledge works. The objection supposes that there should be some basic and fundamental things about which we could not possibly be wrong—perhaps the cogito or the basic experiences that the phenomenalist appeals to—and that knowledge, in order to be knowledge, needs to be based upon these basic and fundamental things. We might call this view foundationalism since the view is that all knowledge, in order to count as knowledge, must be founded upon basic and fundamental beliefs we cannot possibly be wrong about.

Quine argued that this is a mistaken view of knowledge. He suggested instead that our beliefs about ourselves and about the world “hang together” in a kind of web of belief. In a web, all of the strands and their connections rely on other strands and connections; the strength of the whole web is distributed across all its parts. Similarly, in a web of belief, a belief is supported by other beliefs which are supported by other beliefs which are supported by other beliefs including, perhaps, the first belief we started with. Our beliefs are in this sense mutually supportive. This is what it means to say they “hang together.”

According to Quine, we should not expect all of our knowledge to depend upon a few beliefs that are absolutely certain. Rather, we hope that our beliefs support one another in an overall coherent way. We still might regard some beliefs as very central to our web—meaning that many other beliefs depend on them, such as the belief that our senses are not deceiving us. But even these beliefs might be called into question if our other beliefs demand it. Suppose, for example, that we think we see a floating cat, and then our roommates show us a very clever projector they are using to make the image of a floating cat. Now we have to decide whether to believe our roommates and their explanation or to believe our senses that there really is a floating cat and our roommates are lying to us for whatever strange reason. Our other beliefs—for example, that our roommates geek out over technological tricks, and floating cats are not commonly found within anyone’s experience, and holding my hand in front of the projector lens makes the floating cat disappear—eventually persuade us to give up on the floating cat and to believe that it was only a projection. We can imagine different circumstances that would persuade us not to believe our roommates.

But here is another worry we might consider. The person who defends the web-of-belief view, or epistemological holism (as it is called), thinks that our beliefs all hang together in some mutually supportive structure. But might not two people each have mutually supportive webs of belief that disagree fundamentally with one another? Suppose one person believes that humans traveled to the Moon in 1969. A second person believes it was all a hoax. Each person has a mutually supportive web of beliefs supporting their belief about humans on the Moon: one person has all the beliefs we would expect including beliefs about film footage and reports from newspapers and NASA and so on, and the other person has beliefs about government conspiracies and cover-up operations and movie sets made to look like the Moon and so on. We cannot fault either person with inconsistency. But clearly they cannot both have knowledge, can they? So what should we say?

(Can we say that they both have knowledge? So then, it is true for one person that humans traveled to the Moon and true for the other person that it was a hoax? Remember, we are not merely saying that this is what each of them believe. We are talking about knowledge. So we are saying that what is true may vary from person to person and not just for subjective things like favorite colors and banjo tunes, but for all sorts of things, including moon landings, ocean levels, and the shape of Mt. Fuji. Can we make sense of this? We will explore the idea further in the next chapter.)

Supposing for now that “true-for-you-but-false-for-me” is not an option, what is the epistemological holist to say about the Moon landing case? Quine, and indeed any naturalized epistemologist, would insist that the person who believes in the Moon landing is right, and the other person is wrong. Why? Because, as a matter of fact, we did send humans to the Moon in 1969, and all of the reports from the news and NASA are quite accurate. Remember the virtue of externalism: we can appeal to facts outside an individual’s sets of beliefs. We know the facts in this case, and we can trace how the person who believes in the Moon landing came to have their belief, and we can connect that belief to the facts. We can also trace how the conspiracy theorist came to have their belief and connect that belief to facts about paranoia and spurious claims made by other paranoid people. Case closed.

Objection: But wait! Who is to say that Quine’s overall web of belief, which tells him that the Moon landing person is right and the other person is wrong, is the right web of belief to have?

Well, Quine would say, we are the ones to say—those of us who share a naturalized worldview. Of course, we will all admit that we might be wrong. But until some better web of beliefs comes along, we will keep on with the one we have. If in raising your objection you are expecting Quine to produce some fact as solid as iron that will favor one web of belief over another, then you are still using the mistaken foundationalist view of knowledge. We are always in the middle of working out our beliefs from our current web of beliefs, making adjustments where we need to, and trying to keep everything hanging together. There’s nothing more a human can do so far as knowledge goes. And given what we have been able to work out so far, we can be pretty sure that humans landed on the Moon in 1969, and people claiming otherwise are simply wrong.

Media Attributions

- Figure 5.2 © Charlie Huenemann is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license