College of Social and Behavioral Sciences

114 Advancing the Right to Health: Lessons for Improving the Negotiation Powers of Medicare

Hannah Willis

Faculty Mentor: Matthew Slonaker (Sociology, University of Utah)

Abstract

The United States (US) spends more per capita on prescription drugs than other high-income countries (Sarnak, Squires & Bishop, 2017). Yet, the high cost of drugs does not translate to better health outcomes. In fact, the US has a significantly lower life expectancy at birth and higher death rates for avoidable or treatable conditions compared to other high-income countries (Gunja, Gumas & Williams, 2023). While various factors contribute to these poor health outcomes, access to affordable medications is a major consideration.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA, 2022) is a recent policy that aims to address the issue of affordable access to prescription medication by granting negotiation power to Medicare. However, for these negotiations to be effective, it is important to examine drug pricing policies in nations that have successfully negotiated drug prices.

In this paper, I contend that the US has an obligation to provide affordable access to prescription medications, alleviate concerns about stifled pharmaceutical innovation, and finally, I review the process of drug negotiations in the United Kingdom and apply them to the proposed Medicare negotiation policy.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ii

INTRODUCTION 1

UNDERSTANDING THE RIGHT TO HEALTH 3

WHY ARE US DRUG PRICES HIGH? 6

LESSONS FROM THE UNITED KINGDOM 9

PROCESS OF FUTURE US DRUG NEGOTIATION 20

REFERENCES 26

Introduction

As a member of a generation that has witnessed an unprecedented surge in drug development, I’ve seen first-hand the life-saving potential of pharmaceuticals. Each year an average of 38 new drugs go to market, potentially saving someone’s life (CBO, 2021). Yet, for many, these life-altering drugs are tauntingly just out of reach. Personally, I witnessed my aunt struggle to afford a needed prescription. It was a frustrating and helpless experience. My aunt who worked and had insurance, conditions that should prevent extraordinary pharmaceutical bills, had to live on a meager budget to afford the medication. I initially thought that my understanding of how a free market works to efficiently allocate resources was flawed. Maybe I was missing something and my aunt was an anomaly? Surely, I thought, the right to health, including access to medications, would be protected in a high-income country like the US. But firsthand experiences in the medical field, listening to stories from my friends and family, and reviewing data about the high cost of drugs has validated and deepened my concern about the accessibility and affordability of drugs in the US.

In contrast to other high-income countries, the US has allowed drug prices to reach soaring heights with little oversight. This is exemplified by the case of imatinib (Gleevec), a leukemia medicine, whose price in the US rose to $8,500 per month, while it remained at $4,500 in Germany (Bach, 2015). Even amid competition and other factors that would normally drive down prices of non-medical products, in the US, the cost continued to rise. Instead of directly addressing concerns, the US stance on containing prescription prices has relied on “market forces” to govern access to healthcare (Augustine, Madhavan & Nass, 2018). But the pharmaceutical industry is not directly tied to competitive market forces, unlike most sectors in the US.

Typically, the free market maximizes consumer choice. Consumers yield power with economic “votes” that influence which goods should be provided and at what price they should be offered (Augustine, Madhavan & Nass, 2018). Ideally, the free market is supposed to be the most effective way to balance consumer values and seller goals (Elegido, 2015). However, the pharmaceutical sector has many intermediaries and significant government privileges (Augustine, Madhavan & Nass, 2018). The pharmaceutical supply chain involves pharmacy benefit managers, wholesalers, retail pharmacies and insurers that make profit at each step. The compounded price is ultimately borne by the patient and/or taxpayer.

The pharmaceutical sector doesn’t fit neatly into the free-market model because insurers and physicians greatly influence what consumers purchase (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf, 2011). In other sectors, consumers have more autonomy with transactions and have significant information available about the product. But the nature of the pharmaceutical sector creates information asymmetry because most individuals are prescribed a certain medication from a physician and individual insurance plans affect what medication is available (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf, 2011). Further, the pharmaceutical industry enjoys research funding from the government and market exclusivity (Augustine, Madhavan & Nass, 2018).

Lastly, both positive and negative externalities related to the pharmaceutical sector impede the free market’s ability to be effective (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf, 2011 and Augustine, Madhavan & Nass, 2018). In economics, an externality is a side effect of industry activity that impacts other parties without being represented in the cost of the product. An example of a positive externality might be the use of vaccines generally benefits a wider population than just the vaccinated patients. Yet, vaccinated patients and their insurers generally bear the cost of the preventative action (Augustine, Madhavan & Nass, 2018). In contrast, a negative externality might be an unvaccinated person reducing herd immunity or increasing the spread of disease (Augustine, Madhavan & Nass, 2018).

Ultimately, pharmaceutical companies have greater freedom in price setting than other sectors. Because of price setting liberty, consumers (patients) are left to foot a large bill. This dilemma evokes the question: Are the wealthy the only ones deserving of life-altering medications?

Fortunately, the US Government has taken steps to reduce drug prices, such as granting Medicare the right to negotiate drug prices (albeit limited to a contained list of drugs). In this paper, I will review the US Government’s moral and legal obligation to affordable drug prices, explore the balance between pharmaceutical innovation and affordability, showcase how other high-income states have lowered drug prices through negotiation, and provide policy recommendations for the upcoming Medicare negotiations.

Understanding the Right to Health and the US Relationship

In 1946, Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Lady of the US from 1933-1945, played a pivotal role in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (United Nations). The UDHR was a landmark achievement in recognizing human rights on an international scale and aimed to prevent gross atrocities while promoting the development of human rights universally (United Nations). Within two years of its entrance, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly adopted the UDHR. For nearly 80 years, the UN has obtained and operated as an international legal personality and significant reputation as a human rights governing body (Behzadi, 1977).

As a founding member of the UN and its involvement in World War II, the US enjoys certain privileges such as a permanent seat on the UN Security Council and consequently, veto power. However, despite a historical presence in championing human rights abroad, human rights violations are fraught within the US (Amnesty International, 2022). Further, the US has only ratified a few international human rights treaties. Namely, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

For a treaty to be legally binding, it must be ratified. Although the US Senate expressed significant reservations1 and understandings of the ICCPR (making it less influential), they ultimately ratified the covenant (Kinney, 2002). This action had a sweeping impact on the human rights community and gave further legitimacy to the UN and human rights governing bodies. Still, the US refrained from committing legally to many other critical instruments like, the International Covenant for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women of 1979, and Convention on the Rights of the Child of 1989 (Kinney, 2002).

The International Covenant for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) represents a glimmering ideal of quality of life and is an essential instrument in promoting societal improvement. The standard of living (based on OECD Better Index data) is significantly higher in member states that have ratified the ICESCR compared to those that have not (OCHR). In a post-COVID world, the right to health (article 12, ICESCR) is increasingly being recognized and was applied during the international allocation of COVID vaccines (Sekalala et al., 2021). Other pieces of political evidence to the right to health include President Roosevelt’s proposed Second Bill of Rights and the UDHR (Maruthappu, Ologunde & Gunarajasingam, 2012). Furthermore, some US states have taken steps to ensure the right to health in their own laws and policies, demonstrating the importance of this right at a local level (Matsuura, 2015). The ICESCR serves as a powerful tool to protect and uphold the right to health and other economic, social, and cultural rights.

Given the international importance and recognition of the ICESCR, it undoubtedly should not be undermined; however, the US remains staunchly opposed to its ratification (Kinney, 2002). Nevertheless, simply because the US has not ratified the treaty, may not absolve the US of a moral and legal obligation to realize and progress the right to health. In fact, there is growing literature that suggests customary international law may legally obligate the US to respect ICESCR (Kinney, 2002). Customary international law refers to legal obligations that develop from common international practice rather than international treaties (Cornell Law School). An example of customary international law is the granting of immunity for visiting heads of state (Cornell Law School). Due to the widespread ratification of the ICESCR, it stands that the ICESCR may be binding on all countries regardless of ratification status (Kinney, 2002).

Explicit within ICESCR is the right to health (Article 12). Part of the right to health assumes access to affordable and available medications (OHCHR). Essential medicines are unavailable when prices are set at unreasonably high rates by the pharmaceutical industry. To abate high drug prices, other high-income states that have ratified ICESCR have, in some way, become involved with negotiating the prices of drugs.

In the US, there is a consensus that “allowing individuals to suffer or die because they cannot afford health care is morally wrong” (Augustine, Madhavan & Nass, 2018 and Lynch & Gollust, 2010). The US can realize and respect the right to health by negotiating for a lower price of drugs. Granting Medicare, the power to negotiate prices is an essential first step. To effectively negotiate prices, it is necessary to look towards similar nations and their negotiation strategies and systems.

Why Are US Drug Prices High? The Pharmaceutical Dilemma

“Capping prices or profits within the drug-supply chain could restrict patients’ access to medicines and result in fewer new treatments” (Pfizer). Innovation, as drug manufacturers say, comes at price. This is a heralded cry from pharmaceutical representatives when faced with cutting costs on drugs. Current US law allows pharmaceutical companies to place profit first and patients second with the understanding that market forces will indicate where, when, and how to innovate life-altering medication. In the face of public outcry about the affordability of medicine, the pharmaceutical industry claims that patients (specifically in the US) can directly access innovative drugs because companies have the freedom to set prices and recoup on research and development investments.

But this is not entirely true. While concerns about a loss of revenue leading to a loss of innovation are rampant amongst the pharmaceutical sector and opponents of public involvement, there is significant research that dismantles this argument (Dranove & Garthwaite, 2020, Gutierrez & Waldrop, 2021 and Conti, Frank, Gruber, 2021). According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), drug manufacturers invest projected profits into research and development (CBO, 2021). In this way, “innovative” drugs are made based entirely on the expected amount of profit (Dranove & Garthwaite, 2020). Due to a focus on profit, “pharmaceutical companies develop drugs to generate gains on their investment—not to develop significantly improved treatments” (Gutierrez & Waldrop, 2021). So, conditions that are historically not as lucrative but have serious health implications, like neglected diseases, are left on the sidelines of drug innovation.

Further, with a profit mindset, drug manufacturers are pushed to create new versions of an already available drug rather than develop a drug which there is no cure for (Conti, Frank, Gruber, 2021). A few years ago, authors Richard Frank, Jerry Avron and Aaron Kesselheim, found that 37% of new molecular entities introduced in 2017 had no or minor clinical benefit over existing treatments (2020). Despite a lack of clinical benefit, many of those drugs were priced at exorbitant rates.

To be fair, pharmaceutical companies are in a unique position. They have to meet the expectations of patients to provide affordable drugs, but they are also legally obligated to provide competitive investment returns to shareholders (Augustine, Madhavan & Nass, 2018). However, some bioethicists argue that pharmaceutical companies have a special obligation that their products are available to those who need them, even when it comes at a cost to shareholders (De George, 2005).

According to an estimation by the Congressional Budget Office, a loss in pharmaceutical revenue would lead to a loss in two drugs over the next decade and 23 fewer in the following decade (Blumenthal, Miller & Gustafsson, 2021). However, given that pharmaceutical companies are incentivized to develop small changes to already existing drugs, it would be unlikely that the loss of drugs are innovative. In the article, “The US Can Lower Drug Prices Without Sacrificing Innovation,” David Blumenthal, Mark Miller and Lovisa Gustafsson write that many would be created to “merely extend patent protections and thus monopolies over existing therapeutics” (2021). Most patents filed by pharmaceutical companies are for minor modifications to drugs already on the market.

The practice where a company extends the life of a patent by making minor tweaks to a drug that often has little clinical benefit to maintain market power is described as “evergreening” (Collier, 2013). For example, when a drug is nearing the end of its patent life, it may be reformulated into an extended release, effectively thwarting generic competition (Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, 2021). In many cases, this leads to a prolonged period of market exclusivity where one pharmaceutical company can monopolize a certain treatment and drive up the price. The argument stands that a loss in revenue will likely only lead to a loss in a few non innovative drugs.

If the private US pharmaceutical industry continues in the market without government intervention, like effective negotiation, it will likely continue to develop ineffective and costly drugs. Further, health policy advocates believe that the current high cost of drugs negates progress of other health reform initiatives. Fortunately, there are examples in Europe where reasonable drug prices are agreed on without hampering innovation.

Lessons from the United Kingdom

As of 2023, the US is one of the highest spenders on health care compared to other high- income countries, yet it ranks significantly lower in health outcomes (Gunja, Gumas, Williams & 2023). In 2021, researchers at the Commonwealth Fund identified that the US spent 17.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) on health care (Gunja, Gumas & Williams, 2023). By a significant margin, the US was the highest OECD2 spender, and yet the US averaged 3 years lower for life expectancy at birth compared to other OECDs (Gunja, Gumas & Williams, 2023). There are a few differences that explain the discrepancy. One being that most peer countries negotiate drug prices in some way3. Hence, it’s reasonable to presume that negotiated drug prices may be a contributing factor to lowered health care spending and higher life expectancies at birth.

The United Kingdom (UK) exemplifies how an OECD can lower drug prices and maintain positive health outcomes. It is important to note, however, that the UK centers on a universal healthcare system called the National Health System (NHS). Unlike the US where coverage is limited to those who can afford insurance or qualify for programs like Medicaid and Medicare, the universal healthcare system provides coverage to all, regardless of income (Shapiro, 2010). There was a consensus, in the UK, following the second world war that there should be an egalitarian and utilitarian approach to healthcare, leading to the birth of the NHS (Shapiro, 2010). The NHS represented a post-war movement in 1948 that sought for health care to “no longer [be] exclusive to those who could afford it but to make it accessible to everyone” (Brain, 2021). The establishment of the NHS reflects a fundamental shift in societal values towards the idea that health is a human right. Hence, healthcare should be accessible to all, regardless of their ability to pay.

Negotiating drug prices in the UK is a complex process that involves several steps but can be distilled into three main steps. First, the clinical and economic value of a drug is assessed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Then, price negotiations with the drug manufacturer and branches of the federal government begin. Finally, an agreement is reached, and the drug is made available for NHS patients.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is a key institution in the UK healthcare system, providing evidence-based guidance and recommendations for the use of drugs and treatments in the NHS. NICE and similar review bodies play a critical role in negotiations for the NHS and its value-based approach, which is a relatively new concept in the UK. Prior to the establishment of these bodies, the UK government negotiated prices without explicit criteria from 1948-1957 (Rodwin, 2021). At the time, the Ministry of Health “negotiated NHS purchase prices individually, [which was] a time-consuming task, without a fixed methodology” (Rodwin, 2021). This approach proved to be burdensome for the government and resulted in poor outcomes. As a result, the pharmaceutical industry ultimately accepted price and earning caps that were similar to those for other government contractors.

In March 2003, NICE published its first guidelines. Initially, NICE only evaluated roughly half of new drugs that came to market (Rodwin, 2021). In doing so, NICE had to prioritize what factors to include for appraisals. Ultimately, NICE reviewed drugs based on “population size, disease severity, resource impact, and whether, without guidance, there would be significant controversy over the evidence on clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness” (Rodwin, 2021). As NICE proved to be a reputable source for drug evaluations, they were able to evaluate a greater proportion of drugs coming to the market.

Underpinning the NICE guidelines are principles centered on being robust, transparent, inclusive, independent, and contestable (Rawlins, 2015). For each piece of guidance, NICE completes at least one systematic review of the current literature. When developing a clinical guideline, though, NICE conducts more than a dozen systematic reviews.

An essential aspect of NICE is its independence from the government and inappropriate stakeholders. NICE is primarily composed of independent members from the academic community and NHS (Rawlins, 2015). One of the unique features of NICE is its emphasis on transparency and inclusivity. NICE seeks input from a range of stakeholders, including clinical specialists, patient groups and industry representatives, who are encouraged to participate in developing guidance via submission of written or oral evidence. The last principle that supports NICE guidance is its contestability. Each draft is given to stakeholders to comment on, and there are several series of appeal mechanisms should a stakeholder wish to contest the guidance. For example, as many as “2000 comments can [appear] on a single clinical guideline” (Rawlins, 2015). If pharmaceutical manufacturers feel inclined, they may appeal to the Department of Health.

Since its conception, NICE has built an impressive reputation and power over the pharmaceutical industry. Today, a positive review from NICE about a drug or device indicates more funding from the NHS. Additionally, most UK prescribers follow NICE guidelines (Castle, Kelly & Gathani, 2022). However, in the event that NICE finds a drug not to be cost effective, manufacturers have two options. They can either lower their price to the NHS or forgo almost all sales to the NHS (Rodwin, 2021). Manufacturers want to avoid forgoing sale to the NHS because NICE is commonly used as external reference pricing for other nations (Rodwin, 2021). To work around this issue, pharmaceutical companies offer confidential discounts to the NHS and maintain their list price (Rodwin, 2021).

In recent years, NICE has expanded its role beyond providing guidance on individual drugs and treatments. The organization has also developed guidance on broader issues such as health inequalities, social care, and public health. These initiatives reflect a growing recognition that healthcare is influenced by a wide range of factors.

Former chairman-designate, Micheal Rawlins, highlighted some key areas of improvement for NICE moving forward in “National Institute for Clinical Excellence: NICE works” (2015). First, he recognized that guidance should be made publicly available. In 1999, the pharmaceutical industry threatened that a draft for guidance could be shared “in confidence” amongst stakeholders. When NICE agreed to keep it private, companies who did not agree with the guidelines leaked the document. This, while not illegal, could create a so-called “false market” because those with information trade shares to their own advantage. To avoid creating a false market, NICE made the draft guideline publicly available and continued to be transparent following that incident.

Rawlins also recognized the need for NICE to use plain language and concepts that are more familiar to the general public when communicating health economics and its guidelines. Health economic language can be highly technical and nuanced, making it difficult for non- experts to understand the implications of NICE’s recommendations. Language and data in all scientific fields can easily be misinterpreted by the media and general public (Peters, 2013). Currently, there is a push from the scientific community to produce Plain Language Summaries and Frequently Asked Questions to counter misinterpretation (Shailes, 2017).

Lastly, Rawlins identified the challenge of accounting for comorbidities in NICE’s guidelines. Comorbidity is the presence of two or more disease/medical conditions in a patient (Divo, Martinez & Mannino, 2014). Many patients, particularly those over 65, have comorbidity (Divo, Martinez & Mannino, 2014). While it is important that comorbidities are accounted for, designing a guideline is challenging. On one hand, listing only a few guidelines is not comprehensive enough for individuals with a nearly unlimited combination of comorbidity (Rawlins, 2015). On the other hand, having an exhaustive list of guidelines is impractical (Rawlins, 2015). Today, NICE is currently undertaking this challenge and looking towards other health guideline bodies.

Part of NICE’s evaluations (used by VPAS and subsequently the NHS) contains a threshold that indicates prices at which a product would be effective for different clinical patient groups. This threshold4 is set at £20,000-£30,000 per quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained (Sampson et al., 2022). QALY is a measure of disease burden on the quality and quantity of life years. It is “anchored” on a cardinal scale of 0–1 (Whitehead & Ali, 2010). 0 indicates death and 4 This proposal spurs multiple ethical considerations. How does society establish pricing? Implicit in this form of pricing is the implementation of social values. What if those social values aren’t representative of the whole population? Today, US representatives aren’t all that representative of their constituents (Schaeffer, 2023). 1 denotes full health (Whitehead & Ali, 2010). This means that if a person lives in perfect health for one year, they have 1 QALY. QALYs are common in health economic research and policy; however, it has been cited as being reductionist5 (Knapp, 2007). For instance, an improvement in health for a mother may also benefit her children. These changes are not captured in QALY. Critics state that a sole threshold for all drugs is not appropriate because NHS expenditures are not uniform (Claxton, 2014). Due to political pressure, NICE allows paying £50,000 per QALY or more for end-of-life care drugs (Charlton, 2019). Still, QALY remains the best practice for health economists and policymakers.

The Department of Health recognized that patients benefit (and so does the overall budget for the NHS) from a faster adoption of the most clinically and cost-effective medications. The Department of Health writes that “commitments in VPAS around patient access and uptake for innovative medicines have had a substantial positive impact on the speed of medicines access in England, ensuring that NHS patients benefit from cutting-edge treatments” (DH Media, 2023). Recently, government funds have poured into NICE to increase its ability to evaluate all eligible drugs and provide a baseline for negotiations. With NICE’s new funding, more drugs will likely be approved for faster uptake by patients.

There are several negotiation and price-setting mechanisms that the single-payer NHS (England) relies on to contain drug costs. Two main instruments are the Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing Scheme (VPAS) and the Statutory Scheme (Castle, Kelly & Gathani, 2022). In the simplest terms, the VPAS is an agreement to control the prices of branded drugs between the NHS, Department of Health and Social Care, and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) (Department of Health & Social Service, ABPI, 2018). The VPAS sets forth admirable goals: deliver clinically effective and cost-effective prescriptions, deliver value for money for the NHS and continue to support life science innovation (Department of Health & Social Service, ABPI, 2018). As part of the VPAS, all Branded Health Service Medicines are covered, including branded generics, in vivo diagnostics, blood products, and dialysis fluids (Department of Health & Social Service, ABPI, 2018). Patented Branded Medicines cost substantially more than generic medicines. Branded Health Service Medicines are negotiated through value-based pricing, NICE and pressure to secure uptake.

In 2019, the Pharmaceutical Pricing Regulation Scheme (PPRS) was succeeded when the VPAS entered into force. Prior to 2019, PPRS relied on profit and general price control methodology to keep drugs affordable (Parliamentary Office of Science & Technology, 2010). Currently, VPAS sets a limit on annual spending and uses a “value-based” approach to pricing. The NHS is evolving to have a “multilayered landscape for drug pricing in the UK” that uses price caps, value-based approach, and myriad policy factors (Castle, Kelly & Gathani, 2022).

The VPAS sets a limit on annual spending of prescription drugs (of the 172 member companies) that ensures the NHS would not pay more than a 2% growth rate annually (Cohen, 2023). The cap is meant to keep drug prices affordable and available. Interestingly, the cap was considered a “win” by the pharmaceutical industry because the longstanding PPRS had set a 1.1% annual growth rate cap (Walker, Borga & Ribeiro, 2019).

To maintain a set annual growth rate of 2%, Member companies pay scheme payments (Parliamentary Office of Science & Technology, 2010). These payments are based on the agreed growth rate and the predicted growth in sales. Member companies must pay the Department of Health and Social Care a fixed percent of their net profit of branded medicines sold to the NHS (Castle, Kelly & Gathani, 2022). However, there are some notable exceptions for scheme payments. Member companies who are small (sell less than £5 million to NHS) are exempt from scheme payments. Further, medium size companies (£5-25 million) are exempt from paying for the first £5 million. Lastly, Member companies who sell new active substances to the NHS within 36 months of launch are exempt.

There has been a historic rise in scheme payment percentages from 5.1% in 2021 to 15% in 2022 (Castle, Kelly & Gathani, 2022). In part, the rise is due to COVID related expenditures. Throughout the pandemic, the 2% annual agreed limit was likely exceeded and caused an increase in the 2022 scheme payments (Castle, Kelly & Gathani, 2022). (Scheme payments will likely increase for the next few years to tamper the pandemic related expenditures). The pharmaceutical industry is particularly concerned because the commercial viability of certain products with low profit margins is required to pay high rebates (Castle, Kelly & Gathani, 2022).

The former PPRS focused mainly on price control, which remains a component of the new method, VPAS. Under VPAS, a Member cannot increase a list price without prior consultation with the Department of Health (Parliamentary Office of Science & Technology, 2010). They must provide a justification for raising the price and undergo an evaluation of their profits to gain approval from the Department of Health. However, Members with new active substances within 36 months of marketing authorization have the freedom to set list prices, which is intended to incentivize pharmaceutical innovation.

VPAS shifted away from PPRS’ profit and general price control methodology (2014- 2019) to value-based pricing in 2019. Value-based pricing is a principle that dictates that drugs will only be approved for use at prices that ensure their expected health benefits exceed the health displaced (Claxton, 2008). In 2015, Bach and Pearson coined value-based pricing as “the price of a drug on data demonstrating its benefits and harms”. This approach incentivizes the development of drugs that provide the greatest magnitude of benefit by using considerable sound data. Since value-based pricing relies on considerable sound data, the NHS uses a cost effectiveness analysis and the implementation of an ICER threshold (Kaltenboeck & Bach, 2018).

The NHS announced that the system saved £1.2 billion through its negotiations (Morris, 2022). However, the UK’s negotiation process is not without limitations and setbacks. Recently, AbbVie and Eli Lilly have pulled out of VPAS (Taylor, 2023). Now, the two companies fall under the Statutory Scheme for Branded Medicines which has historically carried a high repayment percentage. The two large pharmaceutical companies leaving VPAS signals to the UK government that the rising repayment percentage is unsustainable for the pharmaceutical market. Since AbbVie and ELi Lilly pulled out of VPAS in January 2023, it’s not clear how the shift of two large pharmaceutical companies will impact the UK and global market.

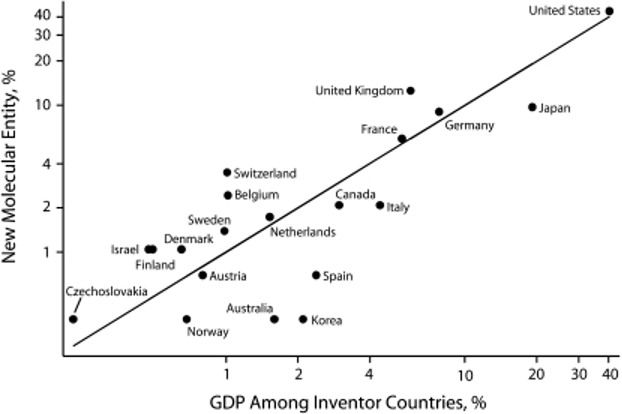

Pharmaceutical innovation is set to improve in the UK. Moreover, drug prices have remained stable due to the price controls and negotiation processes. In 2021, the UK approved 35 new drugs (the EU approved 40 and the US approved 52) on par with another independent OECD, Switzerland (also 35 drugs that year) (Hofer, 2023). At this time, it is unclear whether the transition of Brexit has challenged the approval process for new drugs in the UK. To combat a slower approval process, the UK government has announced a £10 million investment into NICE (Limb, 2023). Despite a slightly slower approval process, the UK outpaced the US in the development of new molecular entities (NME) in proportion to GDP (Keyhani, Wang, Hebert, Carpenter, & Anderson, 2010).

Figure 1. Pharmaceutical innovation as a function of gross domestic product (N = 288): 2000. (Keyhani, Wang, Hebert, Carpenter, & Anderson, 2010)

Medicare negotiations and the Department of Health can learn from the history and current policies that the UK employs to contain costs. First, it is important that the US has some form of rigorous evaluation of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of therapies. However, politics will likely influence which drugs are assessed and what threshold(s) will be available. Arguably, the most effective drug price control as seen in the UK, comes from setting a budget and requiring drug manufacturers to pay rebates when the budget is exceeded. However, should repayment percentages rise too much, pharmaceutical companies could threaten to pull out of the agreement.

Process of Future US Drug Negotiation

After many failed legislative attempts at constraining the rising cost of US drugs, Congress passed sweeping prescription drug pricing reforms as part of the Inflation Reduction Act (August 2022) (Cubanksi, Neuman & Freed, 2023). The Inflation Reduction Act enables the Department of Health and Human Services to negotiate drug prices with the greatest spending for Medicare Part B and Part D through the newly established Drug Price Negotiation Program. According to the Congressional Budget Office, these negotiations are expected to save Medicare $98.5 billion over the next decade (Cubanksi, Neuman & Freed, 2023).

The “noninterference” clause for Medicare Part D, which covers retail pharmaceuticals, and Medicare Part B, physician administered pharmaceuticals, has been a significant barrier to drug price negotiations in the US for a long time (Cubanksi, Neuman & Freed, 2023). The clause cites that the Secretary of Health and Human Services “1) may not interfere with the negotiations between drug manufacturers and pharmacies and PDP [prescription drug plan] sponsors, and 2) may not require a particular formulary or institute a price structure for the reimbursement of covered part D drugs” (Social Security Administration). Clearly, this clause limits the federal government’s ability to lower drug prices, especially for high-priced drugs without competition. Fortunately, the Inflation Reduction Act amended that clause to allow exceptions. The amendment requires the Secretary of Health and Human Services to negotiate single-source brand-named drugs or biologics with no generic or biosimilar competition that are covered under Medicare Part B and D (starting in 2028 and 2026 respectively) (Cubanksi, Neuman & Freed, 2023).

Although the new Drug Price Negotiation Program is a significant step forward towards lowering prescription drug prices, it represents an extensive compromise from the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act (HR 3), which originally proposed broader reforms (Hwang, Kesselheim, & Rome, 2022). The main compromise is the limited number of drugs subjected to negotiation. In the first year (2026) of the Drug Price Negotiation Program, 10 drugs are eligible with 20 being available annually by 2029 (Hwang, Kesselheim, & Rome, 2022). Further limitations on negotiations include extended market exclusivity for drugs. Drugs will be eligible for negotiation only 9 years post launch or 13 years for biologics (Hwang, Kesselheim, & Rome, 2022). Upon entry of a generic or biosimilar competitor, drugs will no longer be eligible for negotiations (Hwang, Kesselheim, & Rome, 2022). If an eligible manufacturer refuses to negotiate, they will be subject to excise taxes (Hwang, Kesselheim, & Rome, 2022).

Similar to the UK, Medicare is expected to review the therapeutic evidence of the intended negotiated drug. As a guideline, legislation has set upper bounds on negotiated prices (“maximum fair price”) (Cubanksi, Neuman & Freed, 2023). Medicare will not spend more than “75%, 65% and 40% of the nonfederal average manufacturer price for 9 to 12 years, 12 to 16 years, and more than 16 years after approval, respectively” (Hwang, Kesselheim, & Rome, 2022). There are many considerations that the Secretary of Health and Human Services must meet (as per the IRA) before setting the maximum fair price. A few of the considerations include accounting for research and development costs, federal aid, current unit costs of production and distribution, market data/revenue and evidence about alternative therapies (Cubanksi, Neuman & Freed, 2023).

Starting in September 2023 the first negotiation process will be about two years. On September 1, 2023, the first 10 Medicare Part D drugs to be negotiated will be published (Cubanksi, Neuman & Freed, 2023). Then negotiation between the Secretary of Health and Human Services and selected drug manufacturers will take place between October 1, 2023, and August 1, 2024 (Cubanksi, Neuman & Freed, 2023). Finally, the negotiated “maximum fair price” will be published on September 1, 2024 (Cubanksi, Neuman & Freed, 2023).

While the Inflation Reduction Act has offered massive improvements for containing drug prices in the US there remain significant limitations. Missing from the Inflation Reduction Act are policies that directly target launch prices. Namely, manufacturers have 9 years of potential market exclusivity. As discussed, other peer countries allow for immediate negotiations at the time of market entry. Further, peer countries do not cap the number of drugs that are eligible for negotiation. Finally, commercially insured individuals are not benefited by the provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act. However, complementary initiatives could support commercially insured individuals.

From a literature review on the UK’s drug negotiations, I recommend three policy recommendations: 1) clarify and develop a method for assessing clinical and cost-effectiveness of a drug, 2) lobby for price negotiations closer to the launch of a new drug, 3) expand the number of drugs for negotiation.

As seen with the case of price negotiations in the UK, having an authoritative body that evaluates the clinical and economic effectiveness of a drug is critical. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) is a US organization that already reviews and makes recommendations on drugs in the US. It conducts a thorough clinical review of “all available data, an understanding of the patient perspective, comparative clinical effectiveness research, long-term effectiveness analyses, potential other benefits, and other considerations” (ICER, 2021). Similar to NICE, ICER encourages stakeholders to engage with the review process and holds public meetings to ensure comments are discussed and considered.

ICER has made a significant impact on drugmakers in the US. For instance, an ICER review of a cholesterol-lowering drug, Praulent, encouraged drugmakers to lower the price to one that was considered fair by ICER (Synnott, Ollendorf & Neumann, 2022). In doing so, Express Script, a large pharmacy benefit manager in the US, expanded patient access to Praluent and offered a portion of the rebates it received to patients (Synnott, Ollendorf & Neumann, 2022).

However, should the US decide to create a new public body for reviewing drug efficacy it could do so with a mix of internal and contracted researchers allowing for federal flexibility similar to the National Institute of Health (Ginsburg & Lieberman, 2021). Additionally, to avoid annual appropriations, creating a Federally Funded Research and Development Center, a nonprofit with a long-term federal contract, could secure multi-year funding (Ginsburg & Lieberman, 2021). Creating a new body would require an impressive initial investment but the payoff of having US value-based assessment and an understanding of local costs would be beneficial.

A final, but least ideal, option is the implementation of reference pricing from other high- income countries. Not investing in a US drug evaluation body would be cost saving initially. But prices in other countries are based on local costs and standards of care as well as societal values (Synnott, Ollendorf & Neumann, 2022). To this end, the US would be implementing other countries’ value assessments that may not align with US values.

A second consideration for US drug negotiations would be the expansion of negotiations at or near drug launch. At the moment, Medicare negotiations are set to include drugs only after they have enjoyed 9 years post launch or 13 years for biologics of market exclusivity (Rome, Lee, Kesselheim, 2020). Researchers (Rome, Nagar & Egilman, 2023) ran a policy simulation of the new Drug Price Negotiation Program if it had been implemented from 2018 to 2020 and found that the 9 year or 13 year protection from negotiation “would have prevented selection of 34 high-spending drugs in 2018”. By delaying negotiation, the federal government risks paying significantly higher drug prices. The same group of researchers also identified in the article, “Trends in prescription drug launch prices, 2008-2021”, that launch price for new drugs increased by 11% per year (Rome, Nagar & Egilman, 2022).

The third recommendation for US drug negotiations is to include a greater number of drugs eligible for negotiation. Currently, the Inflation Reduction Act designed a rigid selection process for drugs. While the top 10 drugs in terms of spending account for a large percentage of Medicare’s Part B and Part D drug spending, it would be more effective to include a greater number of drugs for negotiation (Hwang, Kesselheim, & Rome, 2022). As already mentioned, no other peer country limits the number of drugs available for negotiation.

In the US, where basic healthcare is considered a luxury, the new Drug Price Negotiation Program is an impressive start to lowering drug prices and further advancing the right to health. By reviewing other high-income countries like the UK, we can avoid the pitfalls of ineffective measures and implement beneficial ones that lead to better health outcomes. It is essential that the federal government create a robust system for evaluating clinical and economic effectiveness of drugs, negotiate drugs closer to launch price and expand the number of drugs eligible for negotiation.

It is my belief that everyone deserves the best chance at life, regardless of financial standing. The balance of life and death should not be in the hands of pharmaceutical companies. Making drugs accessible and available through Medicare negotiations is a powerful step towards improving the lives of countless Americans. By implementing successful health policy strategies and recommendations, we can unite and take action to ensure that the right to health is not just a privilege for the wealthy, but a fundamental right meant to be enjoyed by all.

Bibliography

Cornell Law School. (n.d.). Customary international law. Legal Information Institute. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/customary_international_law#:~:text=Customary%20international%20law%20results%20from,for%20visiting%20heads%20of%20state.

Dolan, P. (2001). Utilitarianism and the measurement and aggregation of quality–adjusted life years. Health care analysis : HCA : journal of health philosophy and policy. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11372576/

Dranove, D., & Garthwaite, C. (2020, September 2). Pharma companies argue that lower drug prices would mean fewer breakthrough drugs. is that true? Kellogg Insight. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/pharma-companies- argue-lower-drug-prices-fewer-breakthrough-drugs

Augustine, N. R., Madhavan, G., & Nass, S. J. (2018). Making medicines affordable: A national imperative. National Library of Medicine. National Academies Press. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493099/.

Bach, P. (2015, October 6). A new way to define value in drug pricing. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://hbr.org/2015/10/a-new-way-to-define-value- in-drug-pricing

Bach, P., & Pearson, S. (2015, December 15). Steps to support value-based pricing for drugs. JAMA. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2474095

Blumenthal, D., Miller, M., & Gustafsson, L. (2021, October 1). The U.S. can lower drug prices without sacrificing innovation. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://hbr.org/2021/10/the-u-s-can-lower-drug-prices-without-sacrificing-innovation

Blumenthal, D., Seervai, S., & Bishop, S. (2018, August 22). Three essentials for negotiating Lower Drug Prices. Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2018/three-essentials-negotiating-lower-drug- prices

Brain, J. (2021, June 30). The Birth of the NHS. Historic UK. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Birth-of-the- NHS/#:~:text=The%20National%20Health%20Service%2C%20abbreviated,taking%20its%20first%20tentative%20steps

Castle, G., Kelly, B., & Gathani, R. (2022). Pricing & reimbursement laws and regulations: United Kingdom: GLI. GLI – Global Legal Insights – International legal business solutions. Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://www.globallegalinsights.com/practice-areas/pricing-and-reimbursement-laws-and- regulations/united-kingdom

Charlton, V. (2019). Nice and Fair? Health Technology Assessment Policy under the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 1999-2018. Health care analysis : HCA: journal of health philosophy and policy. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31325000/

Claxton, K. (2014). Causes for concern: Is nice failing to uphold its responsibilities to all NHS patients? Wiley. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/hec.3130

Claxton, K., Briggs , Buxton, Culyer , McCabe , Walker, & Sculpher. (2008). Value based pricing for NHS drugs: An opportunity not to be missed? BMJ (Clinical research ed.).Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18244997/

Cohen, J. (2023, January 23). U.K.’s voluntary scheme for branded medicines, pricing, and Access (VPAS) faces a potential crisis. Forbes. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/joshuacohen/2023/01/19/uks-voluntary-scheme-for-branded- medicines-pricing-and-access-vpas-faces-a-potential-crisis/?sh=27fae70e77c3

Collier, R. (2013, June). Drug patents: The evergreening problem. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal . Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23630239/

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. (2021). Limiting evergreening for name- brand prescription drugs. Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://www.crfb.org/papers/limiting-evergreening-name-brand- prescription-drugs

Conti, R. M., Frank, R., & Gruber, J. (2021, December 15). Addressing the trade-off between lower drug prices and incentives for Pharmaceutical Innovation. Brookings. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.brookings.edu/essay/addressing-the-trade-off- between-lower-drug-prices-and-incentives-for-pharmaceutical-innovation/

Cubanski, J., Tricia Neuman, T., Freed, M., & Damico, A. (2023, January 24). How will the prescription drug provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act affect Medicare beneficiaries? KFF. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue- brief/how-will-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act-affect- medicare-beneficiaries/

Cubanski, J., Neuman, T., & Freed, M. (2023, March 16). Explaining the prescription drug provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act. KFF. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in- the-inflation-reduction-act/

De George, R. T. (2005, October). Intellectual property and pharmaceutical drugs: An ethical analysis: Business ethics quarterly. Cambridge Core. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/business-ethics- quarterly/article/intellectual-property-and-pharmaceutical-drugs-an-ethical- analysis/2C77EB82C5E84CD5DE7DAA08330840C0

Department of Health & Social Care, ABPI. (2018). The 2019 voluntary scheme for branded medicines pricing and access- chapters and glossary. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_da ta/file/761834/voluntary-scheme-for-branded-medicines-pricing-and-access-chapters-and- glossary.pdf

DH Media, D. H. M. (2023, March 28). Voluntary scheme for branded medicines pricing and access (VPAS) – media fact sheet. Department of Health and Social Care Media Centre. Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://healthmedia.blog.gov.uk/2023/03/28/voluntary-scheme-for-branded-medicines- pricing-and-access-vpas-media-fact-sheet/

Divo, M., Martinez, C., & Mannino, D. (2014, August). Ageing and the epidemiology of multimorbidity. The European respiratory journal. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25142482/

Elegido, J. (2015, September). The just price as the price obtainable in an open market . JSTOR. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/24703523

Faunce, T., & Lexchin, J. (2007). ‘linkage’ pharmaceutical evergreening in Canada and Australia. Australia and New Zealand health policy. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17543113/

Frank, R., Avorn, J., & Kesselheim, A. (2020, April 29). What do high drug prices buy us?. Health Affairs. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200424.131397

Ginsburg, P., & Lieberman, S. M. (2021, August 31). Government regulated or negotiated drug prices: Key Design Considerations. Brookings. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.brookings.edu/essay/government-regulated-or-negotiated-drug-prices-key- design-considerations/

Gunja, M. Z., Gumas, E. D., & Williams , R. D. (2023, January 31). U.S. health care from a Global Perspective, 2022: Accelerating spending, worsening outcomes. Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/jan/us-health-care- global-perspective-2022

Gutierrez, G., & Waldrop, T. (2021, September 17). Prescription drugs can be affordable and innovative. Center for American Progress. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/prescription-drugs-can-affordable-innovative/

Human rights in United States of America. Amnesty International. (2022). Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/americas/north-america/united-states- of-america/report-united-states-of-america/

Hwang, T., Kesselheim, A., & Rome, B. (2022, August 19). New reforms to prescription drug pricing in the US: Opportunities and challenges. JAMA. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35984652/

ICER. (2021, September 14). Methods & process: Our approach. ICER. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://icer.org/our-approach/methods-process/

Kaltenboeck , A., & Bach, P. (2018, June 5). Value-based pricing for drugs: Theme and variations. JAMA. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29710320/

Keyhani, S., Wang, S., Hebert, P., Carpenter, D., & Anderson, G. (2010). US pharmaceutical innovation in an international context. American journal of public health, 100(6), 1075–1080. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.178491

Kinney, E. D. (2002). The international human right to health: What does this mean for our nation and world? Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://mckinneylaw.iu.edu/ilr/pdf/vol34p1457.pdf

Knapp, M. (2007). Economic Outcomes and levers: Impacts for individuals and Society. International psychogeriatrics. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17391570/

Limb M. (2023). UK to give “near automatic sign off” for treatments approved by “trusted” regulators. BMJ. 380 :p633 doi:10.1136/bmj.p633

Lynch, J., & Gollust, S. E. (2010, December 1). Playing fair: Fairness beliefs and health policy preferences in the United States. Journal of health politics, policy and law. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21451156/

Maruthappu, M., Ologunde, R., & Gunarajasingam, A. (2012, February 5). Is health care a right? health reforms in the USA and their impact upon the concept of care. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25973184/

Matsuura, H. (2015, July). State constitutional commitment to health and health care and population health outcomes: Evidence from historical US data. American journal of public health. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25905857/

Morris, L. (2022, July 1). NHS negotiating power saving taxpayer £1.2bn on Medicine. National Health Executive. Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://www.nationalhealthexecutive.com/articles/nhs-negotiating-power-saving-taxpayer- 1.2bn-on-medicine-pharma

Mwachofi, A., & Al-Assaf, A. F. (2011, August). Health care market deviations from the ideal market. Sultan Qaboos University medical journal. Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3210041/

OHCHR. (n.d.). Access to medicines – a fundamental element of the right to health. OHCHR. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://www.ohchr.org/en/development/access- medicines-fundamental-element-right-health

Parliamentary Office of Science & Technology. (2010, October). Number 364 Drug Pricing – Parliament. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/post/postpn_364_Drug_Pricing.pdf

Peters, H. P. (2013). Gap between science and Media Revisited: Scientists as public communicators. JSTOR. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/42713438

Price controls could limit patient access to lifesaving medications. Pfizer. (n.d.). Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.pfizer.com/responsibility/ready-for- cures/price_controls_could_limit_patient_access_to_lifesaving_medications

Rawlins, M. D. (2015, June). National Institute for Clinical Excellence: Nice Works. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4480561/

Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Congressional Budget Office. (2021, April). Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57126

Rodwin, M. (2021, March 25). How the United Kingdom controls pharmaceutical prices and spending: Learning from its experience. International journal of health services : planning, administration, evaluation. Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33764174/

Rome, B., Kesselheim, A., & Lee, C. W. (2020). Market exclusivity length for drugs with new generic or biosimilar competition, 2012-2018. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32654122/

Rome, Egilman, & Kesselheim. (2022, June). Trends in prescription drug launch prices, 2008-2021. JAMA. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35670795/

Rome, B., Nagar, S., & Egilman, A. (2023). Simulated Medicare drug price negotiation under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. JAMA health forum. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36705916/

Sampson, C., Zamora, B., Watson, S., Cairns, J., Chalkidou, K., Cubi-Molla, P., Devlin, N., García-Lorenzo, B., Hughes, D. A., Leech, A. A., & Towse, A. (2022, September). Supply-side cost-effectiveness thresholds: Questions for evidence-based policy. Applied health economics and health policy. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9385803/

Sarnak, D. O., Squires, D., & Bishop, S. (2017). Paying for prescription drugs around the world: Why is the U.S. an outlier? Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/media_files_publicat ions_issue_brief_2017_oct_sarnak_paying_for_rx_ib_v2.pdf

Shailes, S. (2017, March 15). Plain-language summaries of research: Something for everyone. eLife. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://elifesciences.org/articles/25411

Shapiro, J. (2010, August). The NHS: The story so far (1948-2010). Clinical medicine (London, England). Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20849005/

Schaeffer, K. (2023, February 28). The changing face of congress in 8 charts. Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/short- reads/2023/02/07/the-changing-face-of-congress/

Schneider, P. (2022, May). The Qaly is ableist: On the unethical implications of health states worse than dead. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9023412/#:~:text=A%20long%2Dstanding%20criticism%20of,of%20’more%20healthy’%20individuals.

Social Security Administration. (n.d.). Subpart 2—Prescription Drug Plans; PDP Sponsors; Financing. Social Security. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1860D-11.htm

Synnott, P., Ollendorf, D., & Neumann, P. (2022, May 6). A value-based approach to America’s costly prescription drug problem. Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/value-based-approach- americas-costly-prescription-drug-problem

Taylor, P. (2023, January 16). AbbVie, Lilly pull out of UK voluntary drug pricing agreement. pharmaphorum. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://pharmaphorum.com/news/abbvie-lilly-pull-out-of-uk-voluntary-drug-pricing- agreement#:~:text=AbbVie%20and%20Eli%20Lilly%20have,signal%20to%20the%20UK%20government%22.

United Nations. (n.d.). Human rights day – women who shaped the Universal Declaration. United Nations. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.un.org/en/observances/human-rights-day/women-who-shaped-the-universal- declaration

Vincent Rajkumar S. (2020). The high cost of prescription drugs: causes and solutions.Blood cancer journal, 10(6), 71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-0338-x

Vogler, S., & et al. (2017). How can pricing and reimbursement policies improve affordable access to … ProQuest. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://www.proquest.com/docview/1973390391?accountid=14677&parentSessionId=qoT GALmTZ2UJT5vL%2B3XAxcWG8nFq9j0egPR7SAUk8eY%3D&pq-origsite=primo

Vokinger, K., & Naci, H. (2022, December 22). Negotiating drug prices in the US-lessons from Europe. JAMA Health Forum. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2799713

Walker, A., Borga, P., & Ribeiro, A. (2019). PNS140 POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF THE U.K. VOLUNTARY SCHEME FOR BRANDED MEDICINES PRICING AND ACCESS: A REVIEW OF STAKEHOLDER OPINION. Value in Health. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.09.2041

Whitehead , S., & Ali, S. (2010). Health Outcomes in economic evaluation: The QALY and Utilities. British medical bulletin. Retrieved April 17, 2023, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21037243/

Whitehead, S., & Ali, S. (2010, October 29). Health outcomes in economic evaluation: the QALY and utilities. Academic.oup.com. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://academic.oup.com/bmb/article/96/1/5/300011

WHO. (2017). Access to medicines: Making market forces serve the poor. World Health Organization. Retrieved January 22, 2022, from https://www.who.int/publications/10-year- review/chapter-medicines.pdf