College of Social and Behavioral Sciences

105 Perceptions of Caregiving and Family Caregivers’ Desires to Institutionalize

Anna Hsu; Rebecca Utz; Amber Thompson; and Catharine Sparks

Faculty Mentor: Rebecca Utz (Sociology, University of Utah)

Introduction

Family caregivers provide unpaid care and support for older adults or chronically ill or disabled family members. With limitations of long-term health services including a lack of healthcare workers, caregivers prevent the healthcare system from being overburdened. Due to an aging population with overall worse health, caregivers are increasingly crucial to the healthcare system (Hoffman and Zucker, 2016 & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019). For instance, one of the largest groups provide care to those with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias, with over 16 million family caregivers providing more than 17 billion hours of unpaid care (CDC, 2023).

Although family caregivers often express positive perceptions of caregiving, such as meaning, satisfaction, and closer interpersonal relationships with the care recipient, caregivers also face immense burden and stress, which can lead to worsened mental and physical health compared to non-caregivers of the same age (CDC, 2019 & Schulz and Sherwood, 2008). Furthermore, there is a lack of financial, mental, and physical support for caregivers (Schulz and Sherwood, 2008). When caregiving becomes too overwhelming or demanding, families may desire to institutionalize the care recipient in nursing homes or assisted living homes. Previous research on dementia family caregivers has found that caregiver burden is positively associated with the desire to institutionalize, whereas positive aspects of caregiving are negatively associated (Vandepitte et al., 2018 & Fields, Xu, and Miller, 2019). Other cultural or personal factors, such as religion or race/ethnicity, may also influence a caregiver’s desire to institutionalize (Fields, Xu, and Miller, 2019 & Cho, Ory, and Stevens, 2016).

For example, when comparing the caregiving experience by sex, it was found that while there is no significant relationship between caregiver burden and positive aspects of caregiving, there were different effects of each variable on the desire to institutionalize by each sex (Wong, Ng, and Zhuang, 2019). The purpose of this project is to understand how characteristics of dementia family caregivers’, particularly perceived aspects of caregiving, caregiver burden, and sex, influence their desire to institutionalize.

Methods

163 dementia family caregivers enrolled in the Time for Living and Caring study, a 16-week intervention aimed to improve respite time-use satisfaction funded by the National Institutes of Aging. At baseline, participants completed surveys including those used to measure positive aspects of caregiving, caregiver burden, desire to institutionalize, and other demographic variables.

Caregiver burden was measured using the Caregiver Burden Inventory, which consists of 24 statements measured on a 0-4 scale. The five dimensions of caregiver burden are time-dependence, developmental, physical, social, and emotional burden. For each participant, the scores for all items were averaged and multiplied by 24 for a final score ranging from 0-96, with a higher score indicating greater burden. Desire to institutionalize was measured six yes/no questions, which were scored from 1-2. For each participant, the scores for all items were averaged and multiplied by 6 for a final score ranging from 6-12, and the data was recoded so a higher score would indicate less desire to institutionalize. Lastly, positive aspects of caregiving was measured using the Positive Aspects of Caregiving scale, which consists of 9 statements measured on a 1-5 scale about a caregiver’s mental and emotional perception of the caregiving experience. For each participant, the scores for all items were averaged and multiplied by 9 for a final score ranging from 1-45, with a higher score representing a more positive appraisal of caregiving.

Four regression models were used to understand the relationship between these variables on the desire to institutionalize. Model 1 was a bivariate regression comparing caregiver burden and desire to institutionalize, model 2 comparing positive aspects of caregiving and desire to institutionalize, and model 3 used both caregiver burden and positive aspects of caregiving to predict desire to institutionalize. Model 4 was a multivariate regression that also controlled for age, sex, race/ethnicity, caregiver health, caregiver employment, adequacy of income, relationship between caregiver and care recipient, and number of children in the household. Independent t-tests were also used to compare the average caregiver burden, positive aspects of caregiving, and desire to institutionalize scores between males and females.

Results

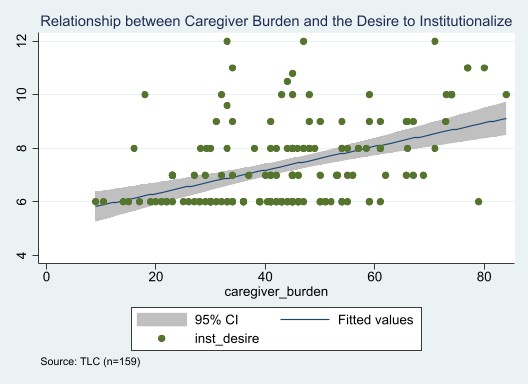

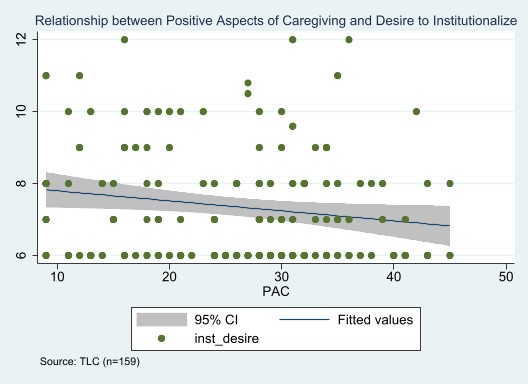

Positive aspects of caregiving and caregiver burden have a moderately weak negative relationship (r=-0.44). As shown in Figure 1, there is a moderately weak, positive association between caregiver burden and the desire to institutionalize (r=0.43). On the other hand, as shown in Figure 2, there is a very weak, negative association between positive aspects of caregiving and the desire to institutionalize (r=-0.17).

Figure 1. There is a weak, positive association between caregiver burden and the desire to institutionalize.

Figure 2. There is a weak, negative association between positive aspects of caregiving and the desire to institutionalize.

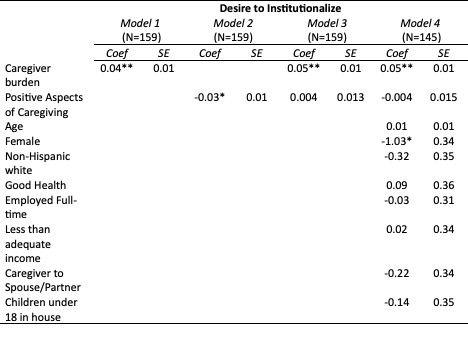

As shown in Table 1, caregiver burden remains significantly positively associated with the desire to institutionalize even when controlling for confounding variables (p<0.001), though positive aspects of caregiving become non-significant when other variables are controlled for (p>0.05).

Furthermore, sex becomes a significant predictor of the desire to institutionalize (p<0.05). While caregiver burden and positive aspects of caregiving are related to the desire to institutionalize, only sex and caregiver burden are significant predictors of the desire to institutionalize.

Table 1. Linear and Multivariate Regression Results for the Desire to Institutionalize

Note. * P>|z| 0.05, ** P>|z| 0.001

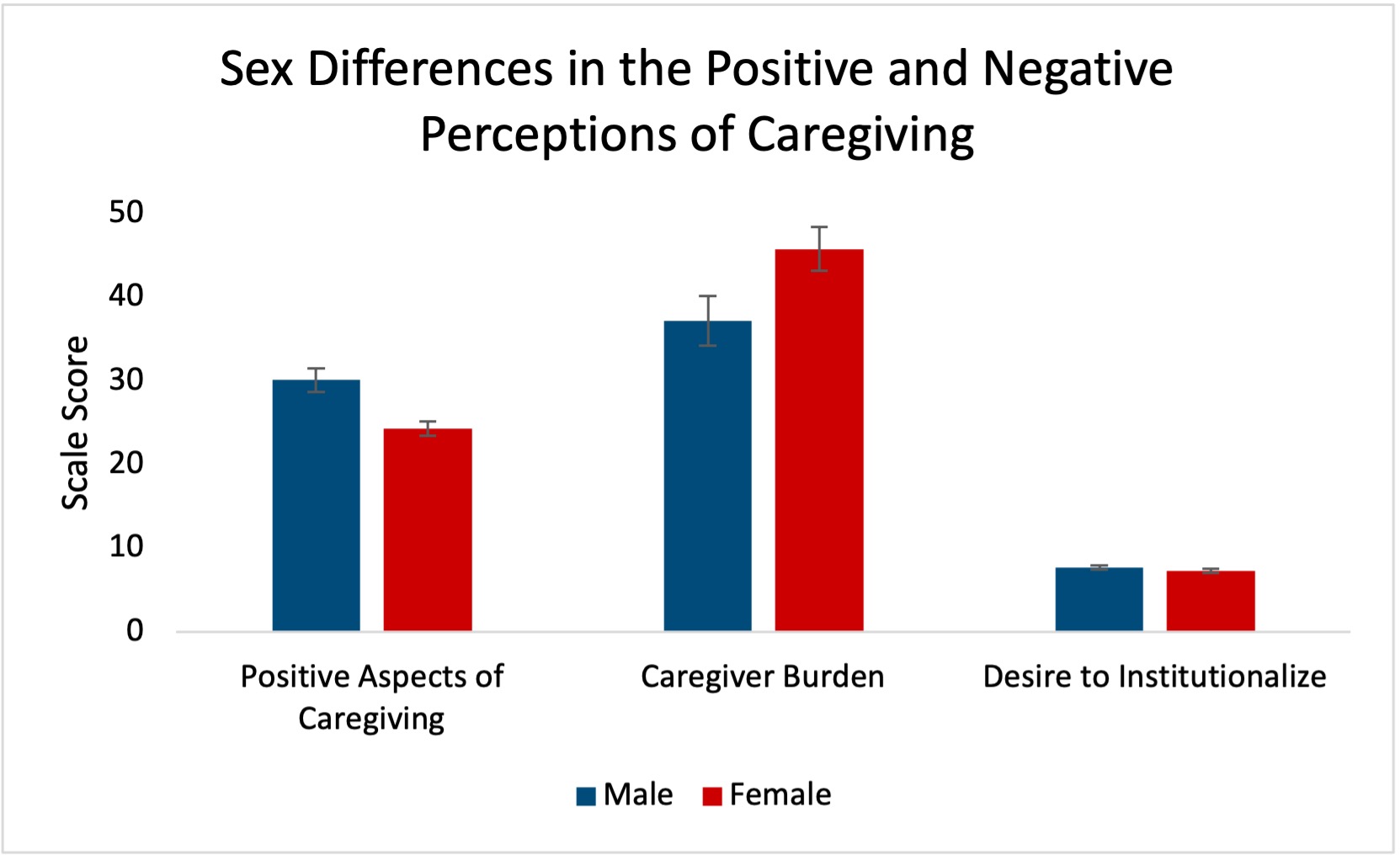

When comparing the summed scale scores of positive aspects of caregiving, caregiver burden, and the desire to institutionalize by sex alone, as shown in Figure 3, when compared to females, males have a higher perceived positive aspects of caregiving score (30.1 (S.D. 8.1) and 24.3 (S.D. 9.9)) and lower caregiver burden score (37.2 (S.D. 17.1) and 45.8 (S.D. 15.0)). However, both sexes have a similar desire to institutionalize score with males having a slightly higher score (7.7 (S.D. 1.7) and 7.3 (S.D. 1.6)). While there is a significant difference in positive aspects of caregiving and caregiver burden by sex (p<0.05), there is no significant difference in the desire to institutionalize (p=0.17). This result suggests that though there may be an association between all three variables, neither positive aspects of caregiving or caregiver burden can predict desire to institutionalize in all cases.

Figure 3. There are significant differences by sex between positive aspects of caregiving and caregiver burden, but no significant difference in the desire to institutionalize. Error bars represent standard error of mean.

Discussion

Although positive aspects of caregiving and caregiver burden are weakly correlated, they are not the same concept, and desire to institutionalize is primarily dependent on caregiver burden. It is important to provide caregivers with the education, support, and resources to help alleviate burden through methods including support groups or formal services such as in-home respite. By managing burden, family caregivers may be better equipped to provide care for persons with dementia for longer, reducing dementia-related institutionalization and preventing the overburdening of the healthcare system.

Acknowledgement: This paper was written under the 2023 Summer Program for Undergraduate Research (SPUR) experience.

Bibliography

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Caregiving for Family and Friends – A Public Health Issue. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/caregiving/caregiver-brief.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Caregiving for a Person with Alzheimer’s Disease or a Related Dementia. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/caregiving/alzheimer.htm

Cho, J., Ory, M. G., & Stevens, A. B. (2016). Socioecological factors and positive aspects of caregiving: findings from the REACH II intervention. Aging & mental health, 20(11), 1190–1201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1068739

Fields, N. L., Xu, L., & Miller, V. J. (2019). Caregiver Burden and Desire for Institutional Placement-The Roles of Positive Aspects of Caregiving and Religious Coping. American journal of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 34(3), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317519826217

Hoffman, D., & Zucker, H. (2016). A Call to Preventive Action by Health Care Providers and Policy Makers to Support Caregivers. Preventing chronic disease, 13, E96. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.160233

Schulz, R., & Sherwood, P. R. (2008). Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. The American journal of nursing, 108(9 Suppl), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c

Vandepitte, S., Putman, K., Van Den Noortgate, N., Verhaeghe, S., Mormont, E., Van Wilder, L., De Smedt, D., & Annemans, L. (2018). Factors Associated with the Caregivers’ Desire to Institutionalize Persons with Dementia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders, 46(5-6), 298–309. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494023

Wong, D. F. K., Ng, T. K., & Zhuang, X. Y. (2019). Caregiving burden and psychological distress in Chinese spousal caregivers: gender difference in the moderating role of positive aspects of caregiving. Aging & Mental Health, 23(8), 976–983. https://doi- org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.1080/13607863.2018.1474447

About the authors

name: Anna Hsu

name: Rebecca Utz

institution: University of Utah

name: Amber Thompson

name: Catharine Sparks