College of Social and Behavioral Sciences

100 The Silent Majority(?): The Insurgent Right in the Southern Cone, 2019-2023

Mauro A. Gonzalez

Faculty Mentor: David De Micheli (Political Science, University of Utah)

Introduction

While pundits have started to claim that Latin America is entering a “second pink tide” (Kirk 2022), there is more nuance than socialists triumphantly re-entering executive office after being exiled to the political wilderness during the 2010s A new, insurgent right has cropped up at the same time: being more conservative, populist, antagonistic, and even authoritarian than their center-right forebearers. This paper examines three recently established right-wing populist parties in the Southern Cone: Chile’s Partido Republicano (PR), Paraguay’s Cruzada Nacional (CN) and Uruguay’s Cabildo Abierto (CA).

Each of the three were newly created for their country’s most recent election cycle and saw strong performances. The Chilean PR has quickly overtaken the center-right Chile Vamos (ChV) coalition, beating them more than 2-to-1 in the first round of the 2021 presidential race (28% to 13%), and garnering 44% of the vote in the runoff. The PR won another stunning victory in the 2023 Constitutional Council elections, totaling 34% of the vote to the center-right’s 20% (SERVEL 2023). The Uruguayan CA got 11% in the 2019 general elections, outperforming the nearly two hundred year-old Colorado party in eight of nineteen departments (Corte Electoral 2019). Finally, the Paraguayan CN got nearly 23% in 2023, right on the heels of the center-left’s 27% (ABC Color 2023b). What’s remarkable is the previous performance of right-wing anti-system parties. Jose Antonio Kast’s (founder of the PR) independent 2017 run for president saw him score nearly 8% of the vote (SERVEL 2017). In Paraguay, an assortment of right-wing protest parties got less than 4% of the vote in 2018 (TSJE 2018). Meanwhile Uruguay did not have a right-wing anti-establishment party compete in 2014. This electoral surge is noteworthy given that the three above-mentioned Southern Cone countries have some of the oldest and most stable party systems in the region. Such a momentous jump in vote shares is rare (Roberts 2014), especially one that so quickly displaces traditional coalitions.

This article seeks to investigate how these parties have managed to find a foothold in well-established party systems. While the parties may differ in certain policy and rhetoric, all three have used appeals to tough-on-crime policies to highlight the failures of the state, romantic nationalism for an antelapsarian past, and the activation of domestic center-periphery tensions to create new coalitions that disrupt the traditional party system. The right-wing insurgents have particularly relied on disenchanted voters on the margins of mainstream politics. These voters tend to be less ideological and more willing to vote for protest candidates, thus taking votes from both left- and right-wing parties. Even if the individual parties don’t survive, the rise in electoral volatility caused by the effective activation of both old (center-periphery) and new (tough-on-crime) divisions perhaps spells future party dealignment.

I. Punitive Populism & Romantic Nationalism

Latin America is “by far, the world’s most violent region,” with one-third of all global violent deaths annually taking place there, while only holding 8% of the total global population. Latin America also hosts forty-three of the fifty most violent cities in the world and seventeen of twenty of the most violent countries (Albarracín and Barnes 2020, 398). Given these conditions, it’s no surprise that violence and citizen security has become one of the most salient issues in the region’s domestic politics, even in locations where there may be lower crime rates (Altamirano, Berens, and Ley 2020; 2022).

In tandem, political entrepreneurs have begun to use the fear of crime in their electoral strategies, leading to the coining of the term “punitive populism.” Populism in this context is to be understood as a type of strategy or rhetorical style. The concerns of “the people” may be disparate, but discontent energy is channeled into a single leader who is able to tie heterogenous demands together to “evoke this chain of commands as the ‘will of the people’” (Bonner 2019, 9). Punitive populism refers to the coalescence of citizen security concerns, banding together the “silent majority” who wish to protect their ordered way of life versus violence, disorder, and those in power who intensify those issues. Punitive populist solutions are broad, ranging from harsher sentencing laws to increased funding of security forces, or even in some cases tacit welfare expansion (Fairfield and Garay 2017; Hathazy 2013) and decriminalization of certain drugs (Caballero 2023). No matter the solution, punitive measures are grounded in anti-establishment politics, pointing to the failure of the state to do its most basic task: protect its citizens. The rhetoric may even take on a certain paternalistic or technocratic demeanor with the presence of military officials within some of the insurgent parties, forming an alliance between the military (the experts who know what to do) and the people (the silent majority who want order) against the politicians (criminals who refuse to follow through with common sense solutions).

With figures like Bolsonaro in Brazil and Bukele in El Salvador having been elected to high office, it’s clear that there is a large voter base in Latin American countries who are willing to engage with authoritarian candidates if it means increasing security. This is no different in the Southern Cone countries, with apologism and nostalgia for previous military regimes being tied to cracking down on crime.

In Chile, the center-right under Sebastian Piñera distanced itself from military dictator Pinochet’s legacy in the 2000s, favoring a modern, pragmatic conservatism that embraced certain welfare reform and deemphasized law-and-order policies. While this won Piñera a wide electoral coalition that saw him serve two terms as President, it sacrificed the Chilean right’s political identity. The center-right and center-left coalitions began converging on political issues, leaving a vacuum for the significant number of Chileans who supported the old regime and its policies. It was Kast and his PR that reasserted this connection to the old right while homing in on contemporary issues, particularly that of crime and insecurity (Campos Campos 2021). While establishing itself during the political upheaval of 2019, the PR’s communications during this time emphasized a “defense of the Republic” both morally (i.e., promoting traditional values) and politically (i.e., with force against criminals and violent individuals). The left is presented as not just the opposition, but as a destructive, violent force that must be stopped. While communications may have lambasted Piñera’s lack of action during the 2019 demonstrations, the Carabineros (Chile’s national police) were spoken in highly positive terms (Campos Campos 2021; Durán and Rojas 2021). Polling data demonstrates that an overwhelming majority of first-round Kast voters in 2021 favored tough-on-crime policies and most had a neutral-to-positive opinion of Pinochet, effectively mobilizing a demographic that had been on the political margins for the better part of two decades (Argote and Visconti 2021a).

In Uruguay, the CA was founded by the sacked Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Guido Manini Ríos in 2019, with an initial coalition of older military men who had supported the dictatorship and a number of smaller right-wing groups that had been established in the earlier part of the decade (Caetano 2022). Embracing a militaristic, caudillo rhetoric, the party anchors itself around the image of Uruguayan Founding Father, General José Gervasio Artigas. An empty vessel by which the CA can construct their own vision, 21st century artiguismo plays on familiar themes of paternalism and militarism, all in the name of defending The Republic against the enemies of societal order, a well-used punitive populist trope (Barrenche 2021; Bonner 2019). The CA’s identification with a romanticized image of the military and its leaders is coming at a time where confidence in the government and its institutions are falling, save for the Armed Forces, which have only become more popular (Caetano 2022). As such, the image of the steward that rises above partisan politics and can re-establish order efficiently can be particularly attractive.

As opposed to the romantic approaches to punitive populism, Payo Cubas in Paraguay has embraced a rough-and-tumble dialogue. He has openly questioned the efficiency of Paraguayan democracy, has called for instituting a state of emergency, establishing the death penalty for patricide, femicide, corruption, and bribery (Décima 2023; Infobae 2023), supports merging and increasing funding for the military and police (La Nacion 2023), and to end drug trafficking in the border region of Pedro Juan Caballero (Caballero 2023). Like the PR in Chile, the opposition is presented as an existential threat, with Cubas stating that “Paraguay has lost” while “the mafia, the narcotraficantes, and the millions of public officials on payroll” have won after conservative technocrat Santiago Peña ascended to the presidency (Última Hora 2023).

The loss of the right’s identity throughout much of Latin America since the 2000s left the doors wide open for new actors to establish a niche where a cautious center-right had refused to. Combining an older, paternal stewardship approach to governance with a modern “politically incorrect” rhetoric regarding pertinent issues such as citizen security, the insurgent right has been able to find a core constituency among those left at the political margins while also making inroads into other, traditionally non-conservative voting blocs.

II. Peripheral Populism

As populist movements see continuing success in both Western and Eastern Hemispheres, scholarly focus has been put on what causes individuals to support populist candidates. One proposal is the “peripheral resentment thesis,” which suggests that the salience of a “periphery-metropole cleavage” drives up resentment among marginalized political groups, leading to the support of anti-establishment candidates (Blatter and Hartmann 2021). I suggest that this “periphery” can be both geographic and political, with any individuals cut off from the centers of power being folded into large anti-incumbent coalitions. This has typically been the case with Latin American populism, where diverse class interests converge against a common foe in the form of the established national government (see for example Drake 1978; Roberts 2002).

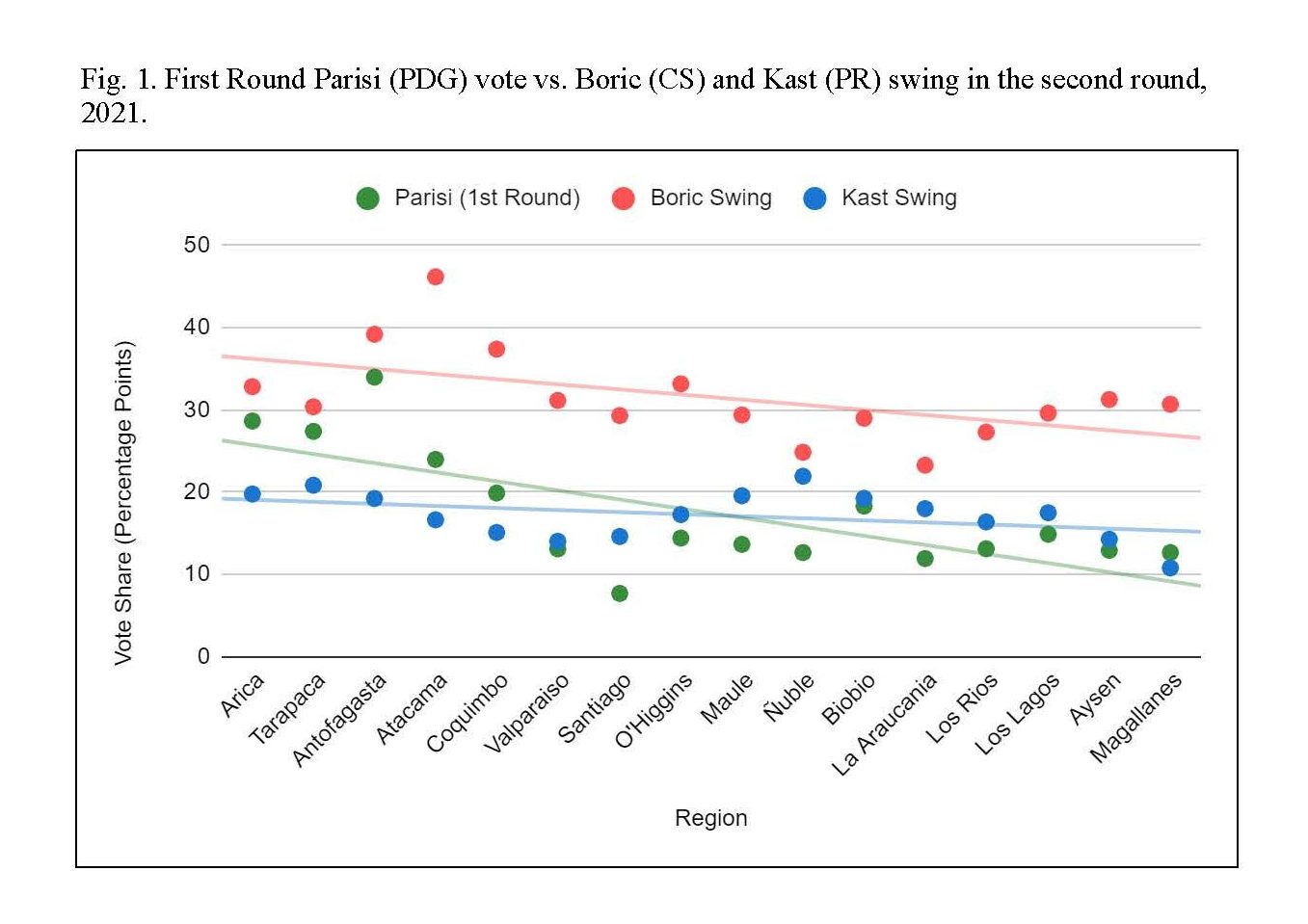

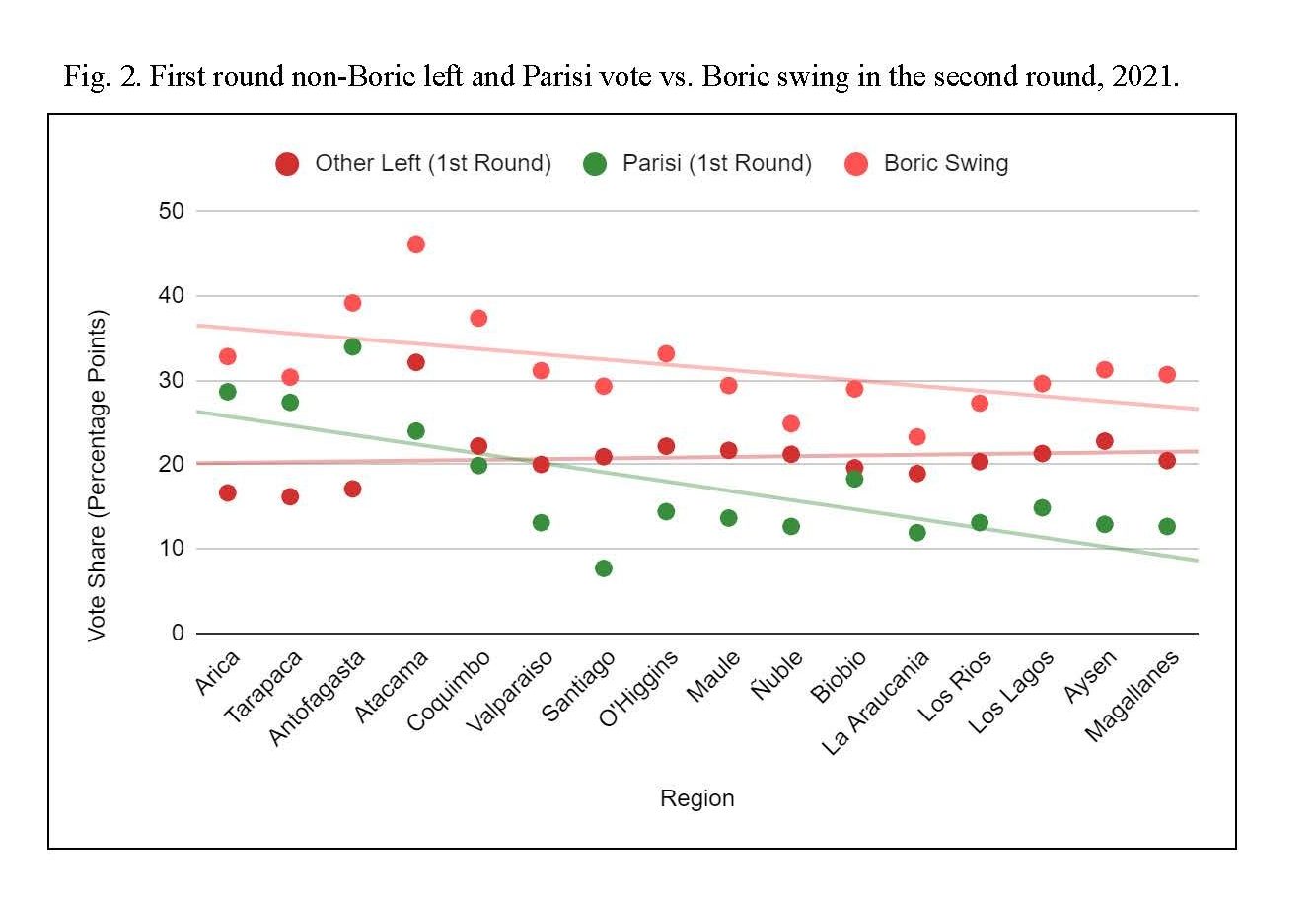

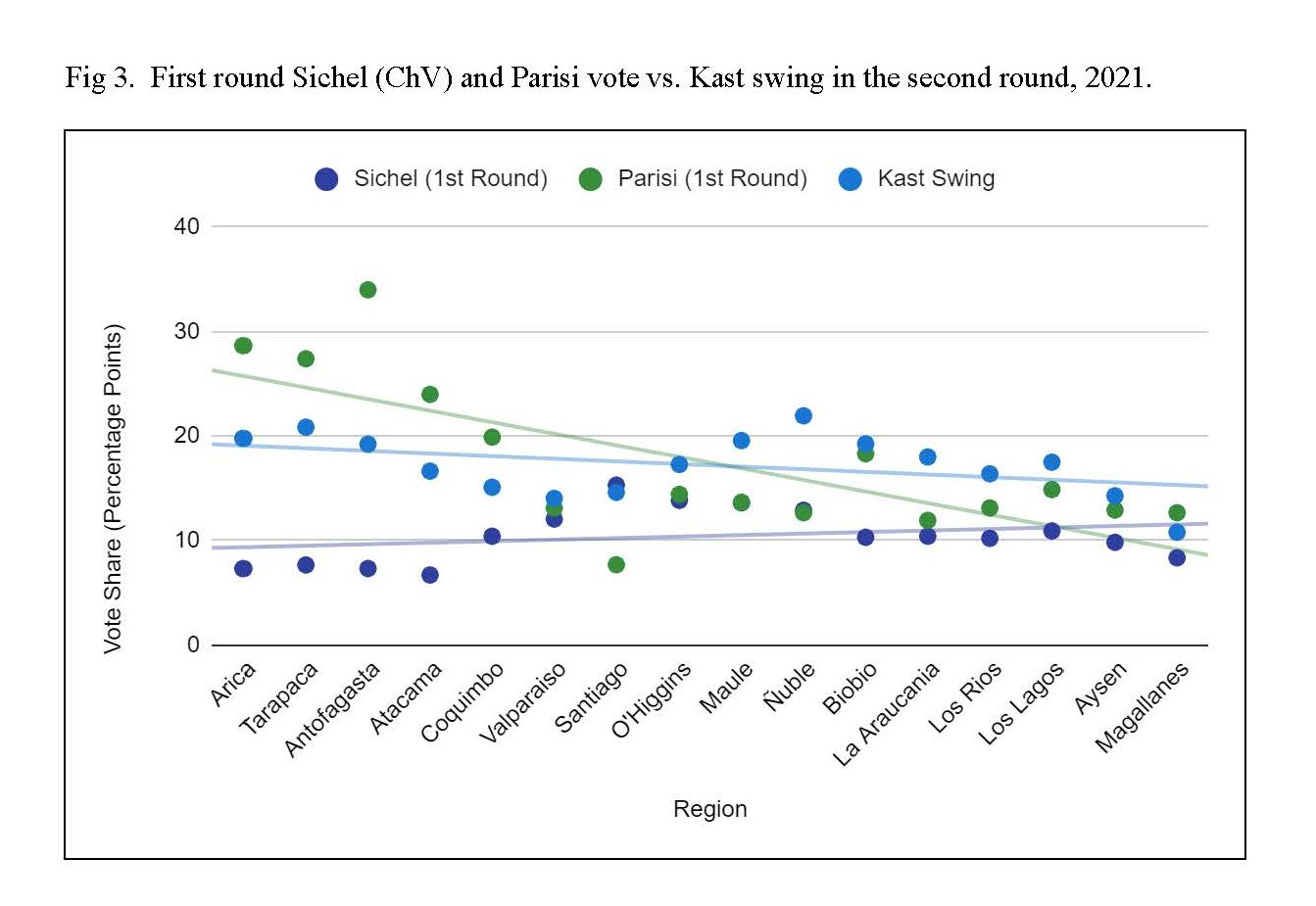

In all three cases, there is a strong geographical element to where the insurgent populists managed to establish themselves. In Chile, there has been long-standing tensions between the economic and cultural center of the Central Valley versus the outer provinces. In the early- and mid-20th century, leftist and populist candidates effectively brought together multi-class coalitions composed of urban laborers from the center along with the working- and middle-classes from the frontiers, particularly in the north (Drake 1978). Recent elections have continued this pattern of center-periphery tensions, with the watershed 2021 presidential race seeing right-wing populists establish strongholds north and south of the Valley. During the first round, Kast and “no labels” populist Franco Parisi won three of the five northern regions, and either one of the candidates got second place in all five. Kast also managed to win every province south of Santiago besides Magallanes, with his stronghold in the central-south. The second round kept this pattern up. Leftist Gabriel Boric managed to pick up most of the northern and southern extremes of Chile as center-left and Parisi voters broke for the left, while Kast still dominated the central-south (Argote and Visconti 2021c, Pauta 2021). However, after two years of an unpopular left-wing government and the failure to ratify a new constitution, the 2023 Constitutional Council election saw the PR win a plurality in every province except Atacama, Coquimbo, and Metro Santiago in the center-north and Los Ríos in the south (SERVEL 2023).

Similar (though not as dramatic) patterns can be seen in Uruguay and Paraguay. While the well-established Uruguayan parties dominated most of the country, the CA saw its strength in the linguistically and culturally distinct northern frontier (Larrouqué 2020) which elected four of eleven CA deputies in 2019 (Corte Electoral 2019). Similarly, Paraguay’s CN won a plurality of votes in the eastern department of Alto Paraná in 2023’s presidential contest, while nearly tying for second place in the frontier departments of Amambay, Canindeyú, and Presidente Hayes (ABC Color 2023b). Cubas went out of his way to appeal to voters on the periphery, specifically acknowledging the presence of drug traffickers among the border regions with Brazil (Caballero 2023), and regularly spoke in Guarani while on the stump in the countryside and among working-class audiences (Carneri 2023).

Paraguay has been dominated by the Colorados since the late 1940s – before, during, and after the Stroessner regime. Their only non-Colorado President, leftist Fernando Lugo was impeached in what was widely considered a parliamentary coup in 2012 (Roberts 2014). Chile meanwhile has had a heavy top-down technocratic political culture inherited from the Pinochet regime. Simultaneously, there has been a large-scale ideological convergence among the mainstream parties. Due to this, both Paraguayans and Chileans have extremely low party identification and high mistrust of parties (Morales Quiroga 2014; Villaga 2011). With the popular sectors vastly unswayed by any party, what counts as the periphery could potentially be expanded by political entrepreneurs who manage to capture the popular imagination against highly centralized, unpopular systems of governance, bringing together new and disruptive coalitions as uncommitted voters turn against the parties they previously voted for.

III. Multi-Sector Coalitions

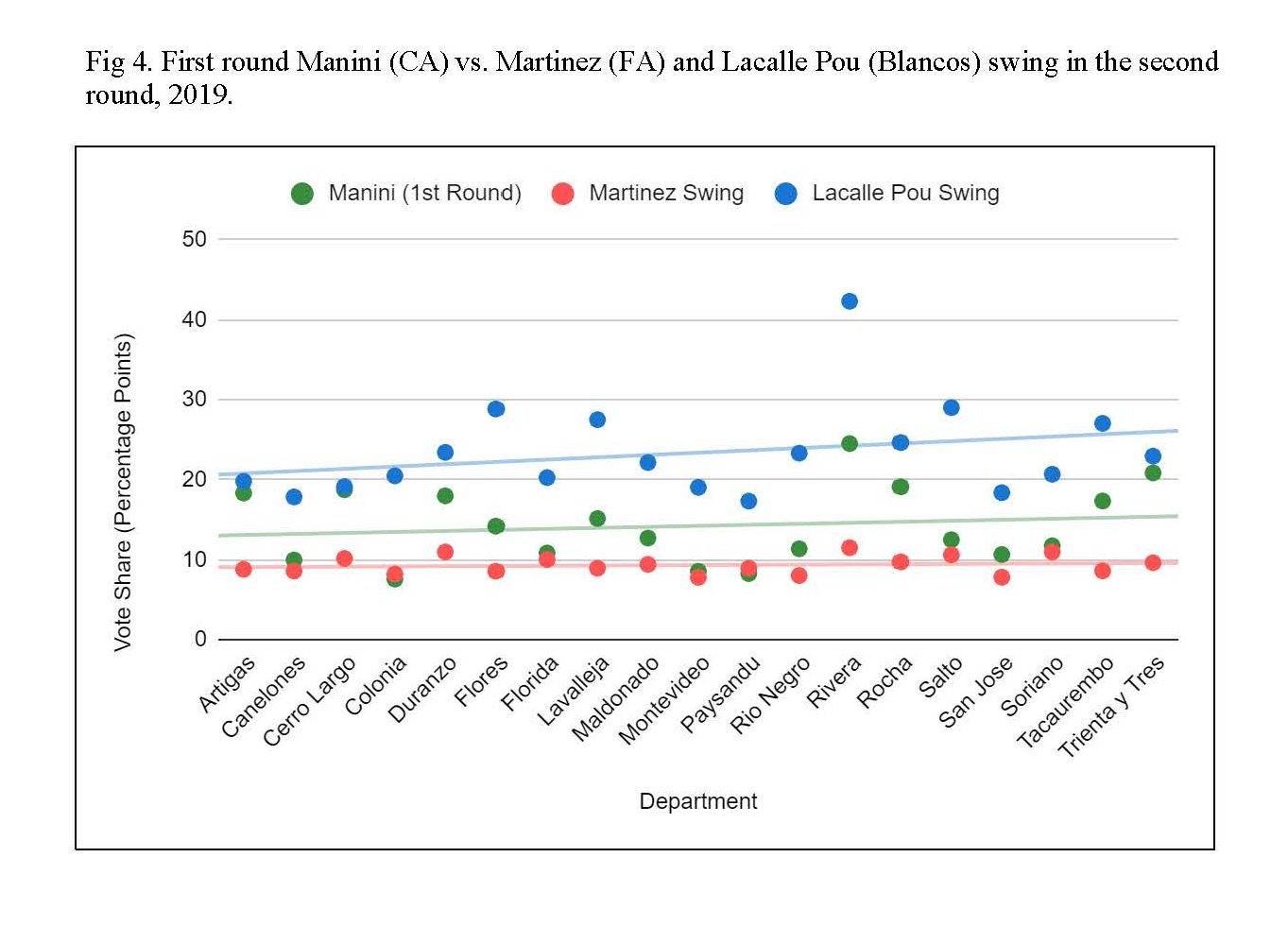

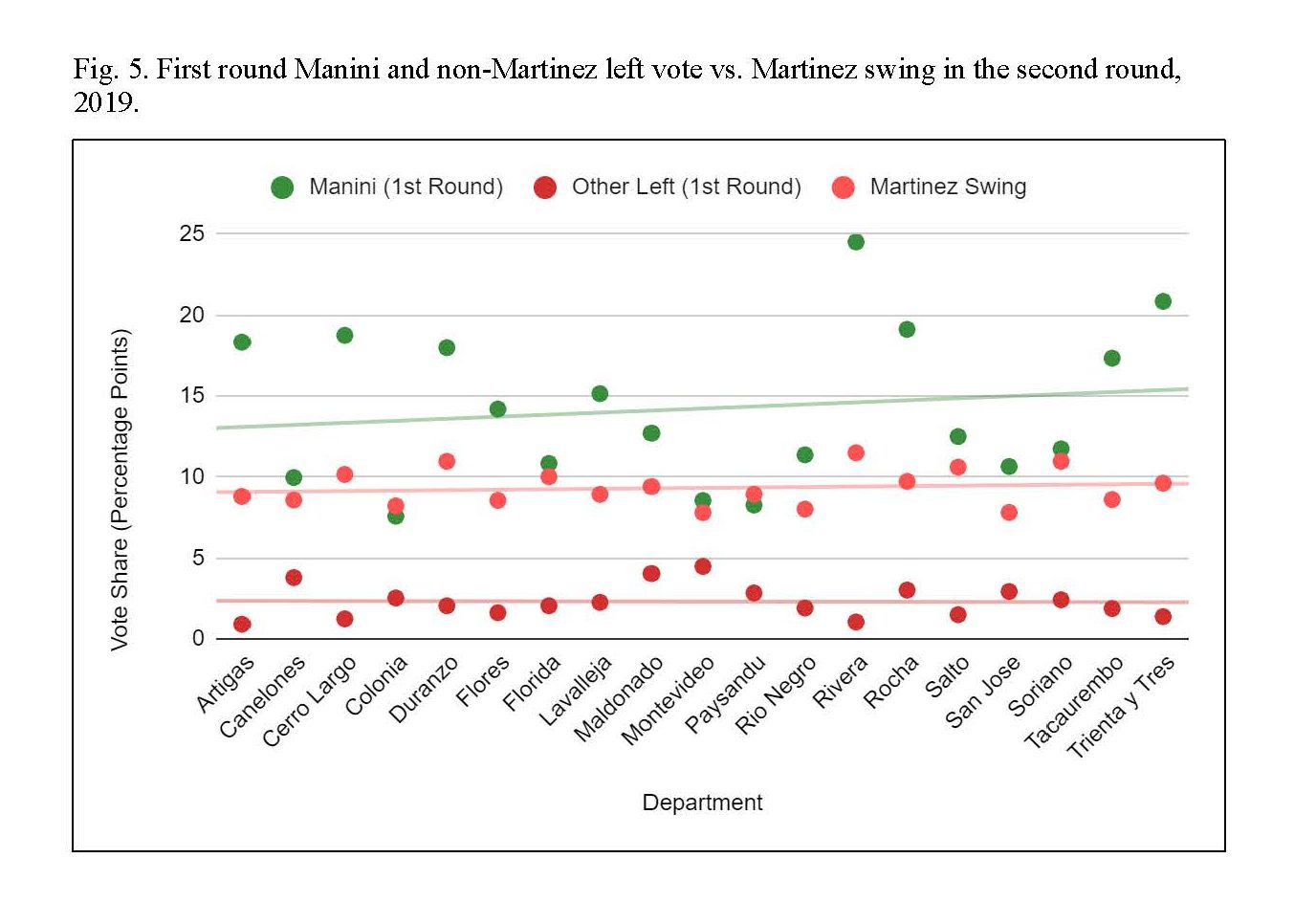

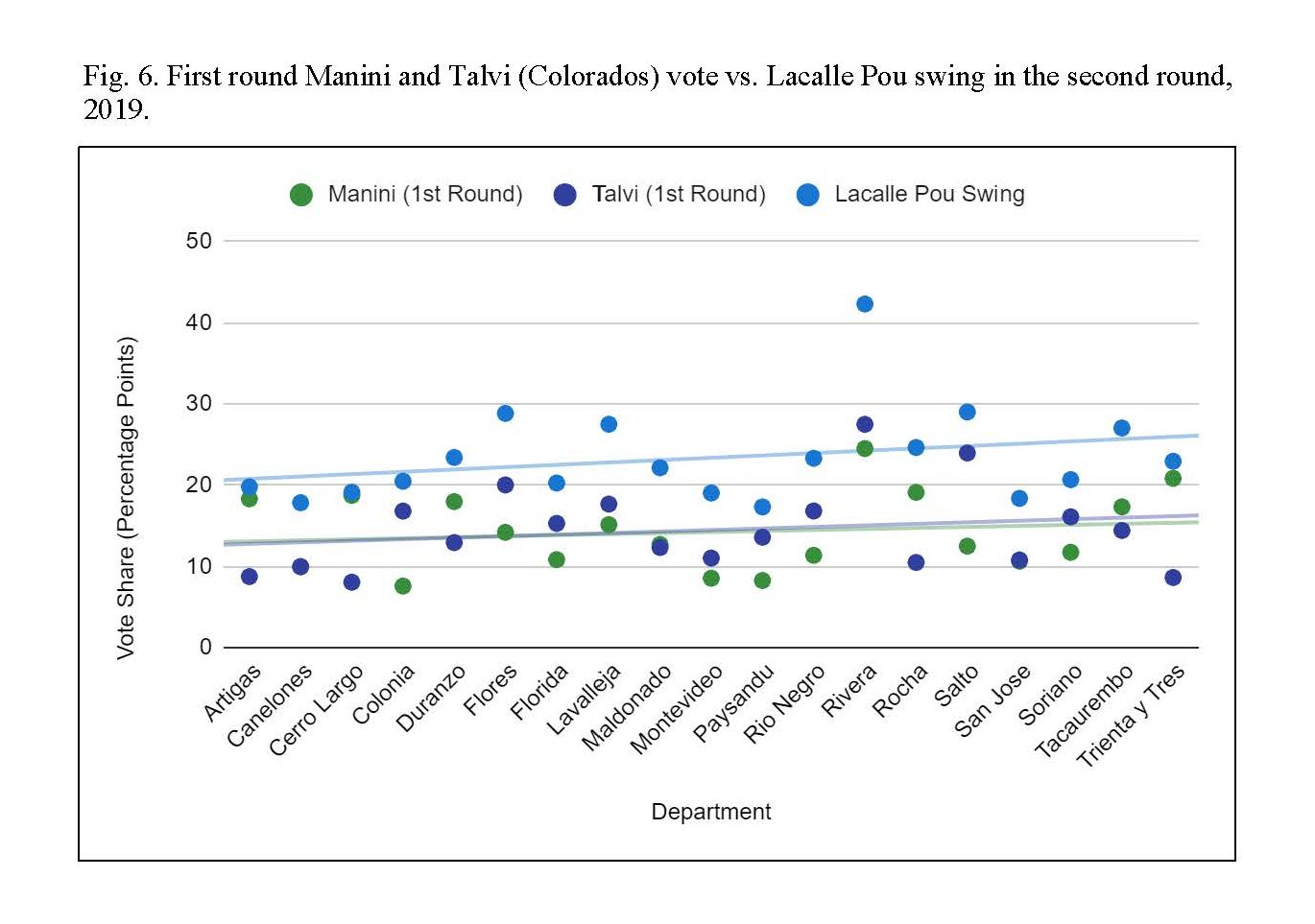

One of the most intriguing factors in the right-wing insurgency is the crossover appeal of the new populists, having taken votes from both right- and left-wing parties. In the 2019 Uruguayan elections, the CA attracted a significant portion of rural voters from the Frente Abierto (FA), Uruguay’s main leftist coalition (Caetano 2022, Larrouqué 2020). In one election-day poll, 38% of CA voters said they voted for the Blancos in the previous election (2014), another 24% said they voted for the FA, and 21% for the Colorados, much more heterogeneous than either the Blancos or the FA. Ideological identification was also more split: 59% of CA voters identified themselves as being right-wing, 35% as centrist, and 6% as leftist, with only Colorado voters being more evened out at 46-44-10 (El Observador).

In Paraguay, Cubas was himself arrested as a youth for participating in anti-Stroessner demonstrations and was a founding member of the center-left Encuentro Nacional party that was part of Lugo’s Concertación coalition (ABC Color 2023a). In an AtlasIntel poll taken a week before the elections, over one-third of previous non-voters (38.8%) and those who spoiled their 2018 ballots (35.4%) indicated they were going to vote for Cubas. Third-party voters were similarly attracted to Cubas, along with nearly 20% of both Colorado (19.6%) and Concertación (17.7%) voters, indicating a highly heterodox coalition (AtlasIntel 2023).

Chile may be a partial exception. In 2021, first round Kast voters were overwhelmingly conservative and pro-Pinochet, showing that the PR were unable to capture a large ideological net at the time (Argote and Visconti 2021a). The candidate able to bring together an “anti-party” coalition was economist Franco Parisi, with his Partido de la Gente (PDG). In one survey, 45% of Parisi voters did not identify with any part of the political spectrum. Of the 55% who did, most identified with the center. A vast majority of Parisi voters agreed that they preferred independent politicians, with their political views scattered between being more liberal on social issues like abortion and gay marriage than the general public, but also were more in favor of immigration restrictions, tough-on-crime policies, and reducing the size of the state (Argote and Visconti 2021b). The Parisi vote split relatively evenly between leftist Boric (42%), rightist Kast (23%), and abstention (35%) in the second round (Argote and Visconti 2021b). Following this pattern, Boric’s second-round victory relied on picking up moderate voters who were more likely to want immigration restrictions and penal policies (Argote and Visconti 2021c). However, as previously mentioned, this coalition quickly collapsed. The 2023 Constitutional Council election saw the PR ride a wave of discontent from everywhere outside the Santiago axis, earning 34.34% of the vote. A now-united left coalition only got a dismal 28% to the combined left’s 49.4% in the 2021 convention elections (SERVEL 2021a; 2023), pointing to Boric’s second round voters jumping ship to a newly invigorated PR.

The realignment between the 2021 and 2023 elections in Chile are a good demonstration of the ideological diversity that can sprout within insurgent populist coalitions in a short time. While the core voters of the insurgent right parties may be right-wing (with the PDG being the exception), it’s necessary to win over uncommitted centrist and leftist voters in order to bring in high electoral shares. The fact that this seems to be occurring in all three countries demonstrates the potency of the insurgent populists, and that it is well within the realm of possibility for them to expand beyond traditional right-wing sectors.

Conclusion

The Southern Cone countries have been well known for their stable, institutionalized, and nationalized party systems. For Paraguay and Uruguay, their party system has lasted for well over a century (close to two for Uruguay), while scholars have argued that the Chilean party system has remained relatively intact even through the Pinochet dictatorship (Bonilla et al. 2011; Roberts 2014). The rise of right-wing insurgents brings these assumptions into question and reflects a more nuanced analysis of said party systems. In particular, examining low identification, lack of party nationalization, and high levels of mistrust (Morgenstern, Polga-Hecimovich, Siavelis 2012; 2014). It raises questions of how much longer the centuries’ old party systems of Paraguay and Uruguay can last: whether there’ll be a shift away from traditional party dominance, or if the insurgents will be swallowed into the traditional coalitions (as has happened in the past). For Chile, it raises the question of whether the country’s party system is a glass cannon, seemingly invincible from the outside but cracks when put through the wringer of societal crisis.

As the populist phenomenon digs its heels in, it’s necessary to investigate the profile of the populist voter. Having a fuller profile of the swing voter in the above-mentioned elections will be useful in seeing where the establishment parties have lost the most ground, and if there’s a correlation to the types of anti-establishment insurgencies occurring in Western Europe, especially in relation to class. The periphery resentment thesis also offers a rich line of inquiry into understanding the evolution of party systems and requires further application in both contemporary environments in either hemisphere, along with in-depth historical analysis with specific case studies. Further inquiry into the role of the Latin American right within the “Reactionary Internationale” (Caetano 2022) is also critical. To what extent are political entrepreneurs (and their voters) explicitly relying on the mold set up in other countries? See for example Larrouqué (2020) who suggests this occurred with the Brazilian-descended CA voters in rural Uruguay, looking towards Bolsonaro. Or are these movements more “home-grown,” relying on the signs and symbols of their country’s own history and culture to create a unique populist movement (e.g., artiguismo in Uruguay, bolivarianismo in Venezuela)?

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my mentor, Dr. David De Micheli for giving me the opportunity to work with him this summer and to learn the ropes of political science research. He allowed me to both work on his project while also conducting my own independent research, which has borne fruit in the form of the paper above. Additionally, I would like to thank my parents, Carlos Gonzalez and Giorgia Roncagliolo, for being supportive of my journey to Salt Lake City, with additional gratitude to the elder Gonzalez for the many enlightening conversations that wound up in this paper. Similarly, thank you to dear friends Tiberius Rocha Magalhães and Sydney Mitchell for going over my paper on short notice, with Ms. Mitchell taking a fine-tooth comb to every word and comma I put down. Every technician needs an English major to make sure their work is legible. Finally, to Andy, Alex, Emily, Lillian, Megan, Owen, Paulina, Riley and Wyn: thank you for making this the best summer I’ve had so far. We’ve made it out of Benchmark, somehow.

Bibliography

ABC Color. 2023a. “Paraguayo Cubas: ¿Quién Es El Candidato a Presidente Por El Partido Cruzada Nacional?” 29 April. https://www.abc.com.py/politica/2023/04/29/paraguayo-cubas-quien-es-elcandidato-a-presidente-por-el-partido-cruzada-nacional/ (July 20, 2023).

———. 2023b “Los Números Definitivos de Las Elecciones: Así Quedaron Los Votos.” 26 May. https://www.abc.com.py/politica/2023/05/26/los-numeros-definitivos-de-las-elecciones-asi-quedaronlos-votos/ (July 20, 2023).

Albarracín, Juan, and Nicholas Barnes. 2020. “Criminal Violence in Latin America.” Latin American Research Review 55(2): 397–406. Altamirano, Melina, Sarah Berens, and Sandra Ley. 2020. “The Welfare State amid Crime: How Victimization and Perceptions of Insecurity Affect Social Policy Preferences in Latin America and the Caribbean.” Politics & Society 48(3): 389–422.

———. 2022. “Security or Social Spending? Perceptions of Insecurity, Victimization, and Policy Priorities in Mexico and Brazil.” Political Studies.

Argote, Pablo, and Giancarlo Visconti. 2021a. “Entendiendo al Votante de Kast.” TerceraDosis. https://terceradosis.cl/2021/11/23/entendiendo-al-votante-de-kast/ (July 20, 2023).

———. 2021b. “Entendiendo al Votante de Parisi.” TerceraDosis. https://terceradosis.cl/2021/11/24/entendiendo-al-votante-de-parisi/ (July 20, 2023).

———. 2021c. “¿Quiénes Son y Qué Piensan Los Nuevos Votantes de Boric?” TerceraDosis. https://terceradosis.cl/2021/12/22/quienes-son-y-que-piensan-los-nuevos-votantes-de-boric/ (July 20, 2023).

AtlasIntel. “Encuesta Atlas – Elecciones Paraguay 2023.” 2023. https://cdn.atlasintel.org/92d996fd-c8624067-8b91-a7ea2e327fc5.pdf (July 20, 2023).

Barreneche, Sebastián Moreno. 2021. “Artiguismo, restauración y usos estratégicos del pasado: La construcción discursiva de la identidad colectiva asociada al partido Cabildo Abierto.” Cuadernos del CLAEH 40(113): 11–34.

Blatter, Joachim, and Martin Hartmaan. 2021. “Populism as Peripheral Resentment? Emotions, Narratives and Sliding Processes.” Politikwissenschaftliches Seminar, Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaftliche Fakultät, Universität Luzern. https://www.unilu.ch/fileadmin/fakultaeten/ksf/institute/polsem/Dok/Projekte_Blatter/Populism_as_pe ripheral_resentment/Populism_as_Peripheral_Resentment_Summary.pdf (July 20, 2023).

Bonilla, Claudio A., Ryan E. Carlin, Gregory J. Love, and Ernesto Silva Méndez. 2011. “Social or Political Cleavages? A Spatial Analysis of the Party System in Post-Authoritarian Chile.” Public Choice 146(1): 9–21.

Bonner, Michelle D. 2019. Tough on Crime: The Rise of Punitive Populism in Latin America. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Caballero, Esteban. 2023. “Payo Cubas Phenomenon in Paraguay.” LatinoAmerica21, 12 May. https://latinoamerica21.com/en/payo-cubas-phenomenon-in-paraguay/ (July 20, 2023).

Caetano, Gerardo. 2022. “Novedades y radicalidad de las «derechas alternativas» en el Uruguay reciente. El caso de Cabildo Abierto.” Estudios: Revista del Centro De Estudios Avanzados (49): 29–54.

Campos Campos, Consuelo. 2021. “El Partido Republicano: el proyecto populista de la derecha radical chilena.” Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política 30(1): 105–34.

Carneri, Santi. 2023. “Detenido En Paraguay ‘Payo’ Cubas, El Opositor Que Llama a Movilizarse Contra Un Supuesto Fraude Electoral.” El País, 5 May. https://elpais.com/internacional/2023-05-06/detenido-enparaguay-payo-cubas-el-opositor-que-llama-a-movilizarse-contra-un-supuesto-fraude-electoral.html (July 20, 2023).

Corte Electoral. “Elecciones Nacionales 2019.” 2019. https://eleccionesnacionales.corteelectoral.gub.uy/ResumenResultados.htm (July 20, 2023).

Drake, Paul W. 1978. Socialism and Populism in Chile, 1932-52. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Durán, Carlos, and Gabriel Rojas. 2021. “El Partido Republicano chileno frente al ‘estallido social’: discurso político, identidad y antagonismo.” Revista Temas Sociológicos (29): 223–57.

Décima, Juan. 2023. “Elecciones En Paraguay: Payo Cubas, El ‘Milei Paraguayo’, Que Apuesta al Voto Bronca y Propone Pena de Muerte Para Los Corruptos.” Clarin, 27 April. https://www.clarin.com/mundo/elecciones-paraguay-payo-cubas-milei-paraguayo-apuesta-votobronca-propone-pena-muerte-corruptos_0_aUmA5kM7qR.html (July 20, 2023).

El Observador. 2019. “El 24% del electorado de Manini Ríos votó al FA en 2014, según Cifra”. 31 October. https://www.elobservador.com.uy/nota/el-24-del-electorado-de-manini-rios-voto-al-fa-en-2014-seguncifra-201910312150 (July 27, 2023)

Fairfield, Tasha, and Candelaria Garay. 2017. “Redistribution Under the Right in Latin America: Electoral Competition and Organized Actors in Policymaking.” Comparative Political Studies 50(14): 18711906.

Hathazy, Paul. 2013. (Re)Shaping the Neoliberal Leviathans: the Politics of Penality and Welfare in Argentina, Chile and Peru. Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y Del Caribe / European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 95: 5–25.

Infobae. 2023. “Quién Es Cubas, El Candidato Sorpresa En Paraguay Obtuvo El Tercer Puesto.” 30 April. https://www.infobae.com/america/america-latina/2023/04/30/quien-es-cubas-el-candidato-sorpresaen-paraguay-que-se-consolida-en-el-tercer-puesto (July 20, 2023).

La Nación. 2023. “‘Payo’ Cubas Prevé Realizar Una Fuerte Reforma Constitucional Para El 2024.” 6 April. https://www.lanacion.com.py/politica_edicion_impresa/2023/04/06/payo-cubas-preve-realizar-unafuerte-reforma-constitucional-para-el-2024/ (July 20, 2023).

Larrouqué, Damien. 2020. “Elecciones en Uruguay: derrota del Frente Amplio y autonomización de la extrema-derecha.” Les Études du CERI, (245-246): 80-82

Morales Quiroga, Mauricio. 2014. “Congruencia programática entre partidos y votantes en Chile.” Perfiles latinoamericanos 22(44): 59–90.

Morgenstern, Scott, John Polga-Hecimovich, and Peter M Siavelis. 2012. “Ni Chicha Ni Limoná: Party Nationalization in Pre- and Post-Authoritarian Chile.” Party Politics 20(5): 751–66. doi: 10.1177/1354068812453370.

———. 2014. “Seven Imperatives for Improving the Measurement of Party Nationalization with Evidence from Chile.” Electoral Studies 33: 186–99. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2013.07.002.

Pauta. 2021. “¿A Dónde Se Fueron Los Votos de Franco Parisi En Segunda Vuelta?” 19 December. https://www.pauta.cl/politica/a-donde-se-fueron-los-votos-de-franco-parisi-en-segunda-vuelta (July 20, 2023).

Roberts, Kenneth M. 2002. “Social Inequalities without Class Cleavages in Latin America’s Neoliberal Era.” Studies in Comparative International Development 36(4): 3–33.

———. 2014. Changing Course in Latin America: Party Systems in the Neoliberal Era. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

SERVEL. “Elección de Presidente 2017.” 2017. https://historico.servel.cl/servel/app/index.php?r=EleccionesGenerico&id=187 (July 26, 2023).

———. “Convencional Constituyente 2021.” 2021a. https://historico.servel.cl/servel/app/index.php?r=EleccionesGenerico&id=223 (July 20, 2023).

———. 2021b. “Elección de Presidente 2021.” https://historico.servel.cl/servel/app/index.php?r=EleccionesGenerico&id=232 (July 26, 2023). ———.

2021c. Elección de Presidente 2021.”. https://historico.servel.cl/servel/app/index.php?r=EleccionesGenerico&id=236 (July 26, 2023).

———. 2023. “Resultados Preliminares: Elección de Consejo Constitucional.” https://www.servel.cl/eleccion-de-consejo-constitucional-2/resultados-preliminares-eleccion-consejoconstitucional-2023/ (July 20, 2023).

TSJE. “Resultados de Cómputo Definitivo – Elecciones Generales 2018.” 2018. https://tsje.gov.py/resultadosde-computo-definitivo—elecciones-generales-2018.html

Última Hora. 2023.“Paraguayo Cubas: ‘Han Ganado La Mafia, Los Narcotraficantes, Los Planilleros.’” 1 May. https://www.ultimahora.com/paraguayo-cubas-han-ganado-la-mafia-los-narcotraficantes-losplanilleros-n3060471 (July 20, 2023).

Villaga, Sarah Cerna. 2011. La senda del outsider: factores que explican la emergencia de candidatos exógenos al sistema de partidos en Perú y Paraguay. Estudios Paraguayos 29/30 (1/2): 117-145