Improvising a Chordal Accompaniment to a Melody

Daniel Stevens

Creating a simple chordal accompaniment to a melody is a beneficial skill for many musicians, including both instrumentalists and vocalists. Not only is this skill useful when teaching others, but the activity of learning to improvise a chord progression will help you better appreciate how other composers harmonize melodies.

Improvising a chordal accompaniment involves the development and integration of several musical skills at once. To list every such skill would be a daunting task and perhaps intimidating for some students, but rest assured that by this point in your studies, you have worked on the reading, audiation, listening, and thinking skills needed to embark on this rewarding activity. Accordingly, we present two activities below, the first of which invites you to rely primarily on your musical intuitions as you develop a chordal accompaniment. The second, longer activity risks being overly prescriptive to spell out a more detailed process. We encourage you to work through one or both of the activities depending on your own needs and preferences as a learner. And most importantly, as you work through either process, self-reflect on what works best for you. The insights and strategies you develop through discovery will far outlast the suggestions we make below.

To get started, pick a children’s song or another diatonic melody that you know by ear. We’ll focus on “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” in the activities below, but we encourage you to apply any helpful strategies that you read or discover to other melodies that you know. At the bottom of this chapter, we’ve provided some additional melodies that you can use to develop this skill. Before beginning either activity, learn the given melody as well as you can, either by singing the melody using solfège or scale-degree numbers.

Activity: Improvise a chordal accompaniment to a melody that you know by heart.

Goal: Use your ear and musical intuitions to develop a chordal accompaniment.

Before you start: You’ll need a piano, guitar, or another chord instrument.

Instructions:

- Choose a simple figuration (e.g. boom-chuck, block chords, arpeggiation) that you will use to activate the chords.

- Most simple songs invite starting on the tonic harmony. Try that option first, but depending on the style, you may wish to try other starting chords as well.

- Begin singing the melody while playing your opening chord. As the melody progresses, listen for notes that seem to call for a chord change, making changes that seem appropriate. We recommend singing in solfège since the scale degree of the note that invites a chord change also provides a clue as to what change to make.

- Continue the process of singing, listening, and responding to the melody, and use your theory knowledge to help consider different chordal options when changes are required.

How might you apply the steps in the activity above to create a chordal accompaniment to “Twinkle, Twinkle?” To start, you might begin by exploring a range of accompanimental figurations. As you sing the melody in solfège or scale degree numbers, you’ll probably notice that it begins with 1/do, 1/do, 5/so, 5/so, which invites a tonic opening. This harmony interprets the melody by encouraging listeners to hear the first two pitches (1/do and 5/so) as a chordal skip within the tonic triad. You might decide to interpret the first two melody tones differently and try other harmonic settings, but to be sure, a tonic start is the most common and stable solution.

Let’s assume that you begin on a tonic harmony. As a general rule, it is advisable (and practically expedient) to stay on the same harmony until the melody requires a change. In “Twinkle, Twinkle,” the 6/la that arrives on the downbeat of measure 2 clashes with the tonic harmony and calls for a chord change. Because the note is 6/la, it invites the subdominant harmony (IV, or the four-chord). Other harmonies that contain 6/la include the supertonic and submediant. Feel free to try all three, and consider which options you like the most and why. That said, since this is a practical skill that you may be learning for the first time, you might also find it helpful to stick as closely as you can to three common harmonies: the tonic (I, or the one-chord), the subdominant (IV, or the four-chord), and the dominant (V, or the five-chord).

As the melody continues, listen to the changes of melodic tones that continue on strong beats in the measure (beats 1 and 3). If the notes that arrive on these strong beats clash with the previous chord, a chord change may be needed. Follow your ear as you develop your chordal accompaniment. See how many different harmonizations of the same melody you can create. You can try adding things like first-inversion harmonies or chromatic notes in the bass to find new harmonies.

If you are struggling to produce satisfying results as you work on the exercise above, try the suggestions or alternative approaches given below the second exercise. Like any skill that involves the integration of sub-skills, improvising a chordal accompaniment may take time and intensive practice before you reach proficiency. The slower, more intentional, and more consistent your practice, the faster this skill will develop. Be patient!

Activity: Improvise a chordal accompaniment to a notated melody.

Goal: Apply principles from written theory to develop a chordal accompaniment.

Before you start: You’ll need a piano, guitar, or another chord instrument, as well as a notated melody appropriate for harmonization. A sight-reading anthology is a useful source.

Instructions:

- If you are not familiar with the notated melody, begin by singing the entire melody several times. Consider its overall shape and phrase structure, and listen for which notes seem to be structural or embellishing. Generally, structural notes require a chord change, while embellishing tones (e.g. passing notes, neighbor notes, chordal skips) do not.

- Begin at the end. Does the melody invite cadential closure? If so, which type, and where will the cadential dominant and tonic chords go? Before the cadential dominant, is there a place in which a predominant chord could be used? (If the melody does not seem to require a cadence, consider other ways that it might invite closure.) If the melody consists of multiple phrases, are there other cadence points to consider?

- Study the opening of the melody to determine how you will begin your harmonization. By default, many (but not all!) melodies invite starting on the tonic chord.

- Once the beginning and ending chords of each phrase are set, there usually aren’t many chords needed to fill in the middle. Generally, try to use as few harmonies as possible, changing only when the melody (or your ear) requires it. This principle has strategic value: an accompaniment with fewer chord changes is easier to play and will lead to a better overall performance. Think of this principle like a musical Newton’s law: chords at rest tend to stay at rest unless acted upon. Melodic tones on strong beats that don’t fit the prior harmony often cause the harmony to sound like it needs to change.

- If possible, emphasize tonic chords or chords that lead back to the tonic (for example, IV, or the four-chord, or V, or the five-chord).

- As you develop your chordal accompaniment, be mindful of harmonic rhythm (the rhythm of the harmonic changes, not the rhythm of the figuration). Generally, it is practically expedient to use a consistent harmonic rhythm that uses longer durational values (for example, whole notes and half notes). Doing so enables you to use the same accompanimental figuration without needing to make constant adjustments. If you make a chord change that uses a short duration or that falls on an off-beat, listen carefully to see if it fits well within your overall accompaniment.

- As you harmonize the melody, consider the contrapuntal relationship between the bass and melody. In some styles, you may wish to avoid consecutive fifths and octaves and other problematic voice-leading relationships, but in other styles, more freedom may be exercised.

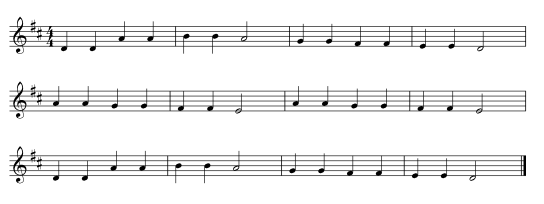

Applying the process above to “Twinkle, Twinkle,” you might have made observations similar to the ones below at each step. The score to this simple tune is given below; it may be helpful to imagine that you do not know this melody already.

- “Twinkle, Twinkle” has a simple three-phrase form (ABA). Aside from the opening leap from 1/do to 5/so, all other note changes occur on strong beats and invite a change of harmony. In other words, almost every note of “Twinkle, Twinkle” will be treated as a structural tone requiring its own harmony.

- The A phrases of “Twinkle, Twinkle” end with 2/re to 1/do in the melody, thus inviting authentic cadences, while the B phrase invites a prolonged emphasis on the dominant harmony (with 5/so in the bass throughout). At the end of the A phrase, the repetition of 2/re also admits using a predominant (ii6, or two-chord in first inversion) on the first 2/re followed by the cadential dominant (V, or five-chord) on the second 2/re.

- In the case of “Twinkle, Twinkle,” the first four notes of the melody (1/do, 1/do, 5/so, 5/so) call for starting on the tonic chord.

- In “Twinkle, Twinkle,” the first two melodic tones (scale degrees 1/do and 5/sol) both fit the opening tonic; neither note forces the chord to change, so a single tonic chord is an excellent choice. On m. 2 (the word “Little”), the move in the melody to la on a strong beat suggests a harmonic change, and the move back to sol on beat 3 invites yet another change.

- To emphasize the tonic, the 6/la in m. 2 and 4/fa in m. 3 could be harmonized by a IV (four-chord) and V7 (five-seven-chord) respectively since these chords lead back to the tonic chord.

- In “Twinkle, Twinkle,” the melody invites chord changes only on strong beats (1 and 3), resulting in a harmonic rhythm of whole-note and half-note durations.

- If you are creating a harmonization of “Twinkle, Twinkle” that reflects conventional tonal practice, you might find, for example, that the interior scale degrees 4-4-3-3/fa-fa-mi-mi in the A phrase would fit the harmonies IV–I6. However, these chords would create outer-voice parallel octaves between the bass and melody, and in this style, should be avoided. Similarly, if the melody has a tendency tone (e.g., chordal seventh, leading tone), avoid placing that note in the bass of the chord progression.

Here are some tips and strategies to employ if you are struggling to create a chordal accompaniment:

- The go-to solution for most students and problems is to play incredibly slowly. Set the metronome at 15-25% (or less) of the tempo marking at which you are currently struggling. Remember: mistakes in music are usually a symptom that your ear, mind, and body didn’t have the time they needed to hear, know, and move in advance of the next required sound. The purpose of going slowly is to give your ear, mind, and body the time they need to coordinate each sound. If you practice too fast, those three components are never given the opportunity to learn how to coordinate, and so no growth or improvement can possibly occur. By going incredibly slowly, you are being a good teacher to yourself by giving your “students” the time they need to learn how to work together. Students who practice slowly for one week are often surprised at how quickly real improvement follows.

- Focus on audiating both the melody and the harmony before you play them. Anytime you find yourself singing and playing notes that you haven’t anticipated internally by ear, your playing process will tilt toward rote learning rather than authentic, creative musicianship. Musical creativity, poise, and control are developed in the ear before you play.

- If you find yourself repeating the same figurations and wish to expand your creative horizons, try opening a volume of lieder (German art songs) by Clara Schumann or Franz Schubert and trying one of the accompanimental patterns that they developed.

- Watch out for non-chord tones that fall on strong beats. For example, the “Happy Birthday” song places an upper neighbor on the downbeat of the song. Look at the entire melodic context when choosing harmonies, not just one note (even if that note is on a strong beat). Relatedly, if a non-chord tone falls on a strong beat, you may find it helpful to use an accompanimental figuration that employs only the bass note on these beats, and wait for the upper voices to enter after that melody tone has resolved. Always aim for a simple, playable accompaniment, even when the melody does something unusual.

- Trust your ears; they will point you in the right direction and help you avoid awkward harmonizations. Just like good writers read their texts aloud to find poor wording, listen carefully to the chord progressions you create and let your ear guide the process from start to finish. Remember: every creative act of music-making–whether in composing, improvising, or performing–is an opportunity to develop your ears!

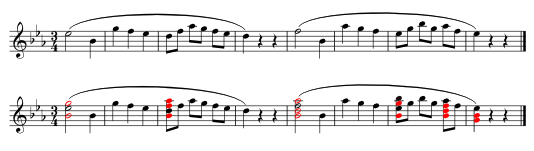

Creating a chordal accompaniment involves quite a lot of careful thinking, listening, and creative exploration. Luckily, the entire process can be aided by donning a pair of “magic chord goggles.” Wearing these imaginary goggles, you can “see” the harmonies around the chords in the melody, and in many cases, you may only need to add one note to fill in the remainder of the chord. Better still, you can often follow the voice leading indicated within the melody. In other words, when you wear your magic chord goggles, you no longer have to “make up” the chords! They are visible right there in the music. For example, consider the melody below, given in its original form and as seen through the magic chord goggles.

Mozart, Symphony No. 39, K. 543, third movement:

You can use the melodies below to try the magic chord goggles for yourself and to practice implementing the instructions for the activities above. After you have created your own chordal accompaniment, you can listen to the original by accessing the playlist below.

[in progress]

Image Attributions |

|