Conducting

Ways of conceptualizing time in music are often associated with physical actions. In the time signatures system, the primary physical motion associated with beats and measures is the system of conducting patterns used by conductors of ensembles like bands, choirs, and orchestras. These specific ways of waving your arm and hand can be useful if you need to lead such an ensemble, but they also are useful in giving you a physical model for what measures of different lengths might “feel like.” Internalized physical models are a very powerful tool to draw on in your listening and music-making, and those embodied, internalized models will be our focus here: if you wish to learn about the art of conducting for its own sake, including cueing, communicating character, clarifying ictus, and more, this is not the best source.

All of the conducting patterns assume that each measure has a “beginning” beat, called a “downbeat,” represented by a downward arm motion. They also assume an “ending” beat, called an “upbeat,” represented by an upward arm motion. Of course, because this is a cycle, the ending simply prepares for another beginning, and the upbeat often feels not like a point of rest but rather a moment of anticipation as the arm rises in preparation for the next downbeat. In between the downbeat and the upbeat are different numbers and directions of hand-waves to represent the number of beats in the measure. Conducting patterns, in their basic form, thus communicate two pieces of timekeeping information:

- the beat (represented by each wave of the arm/hand), and

- the measure (represented by the whole pattern and marked by the return of each downbeat).

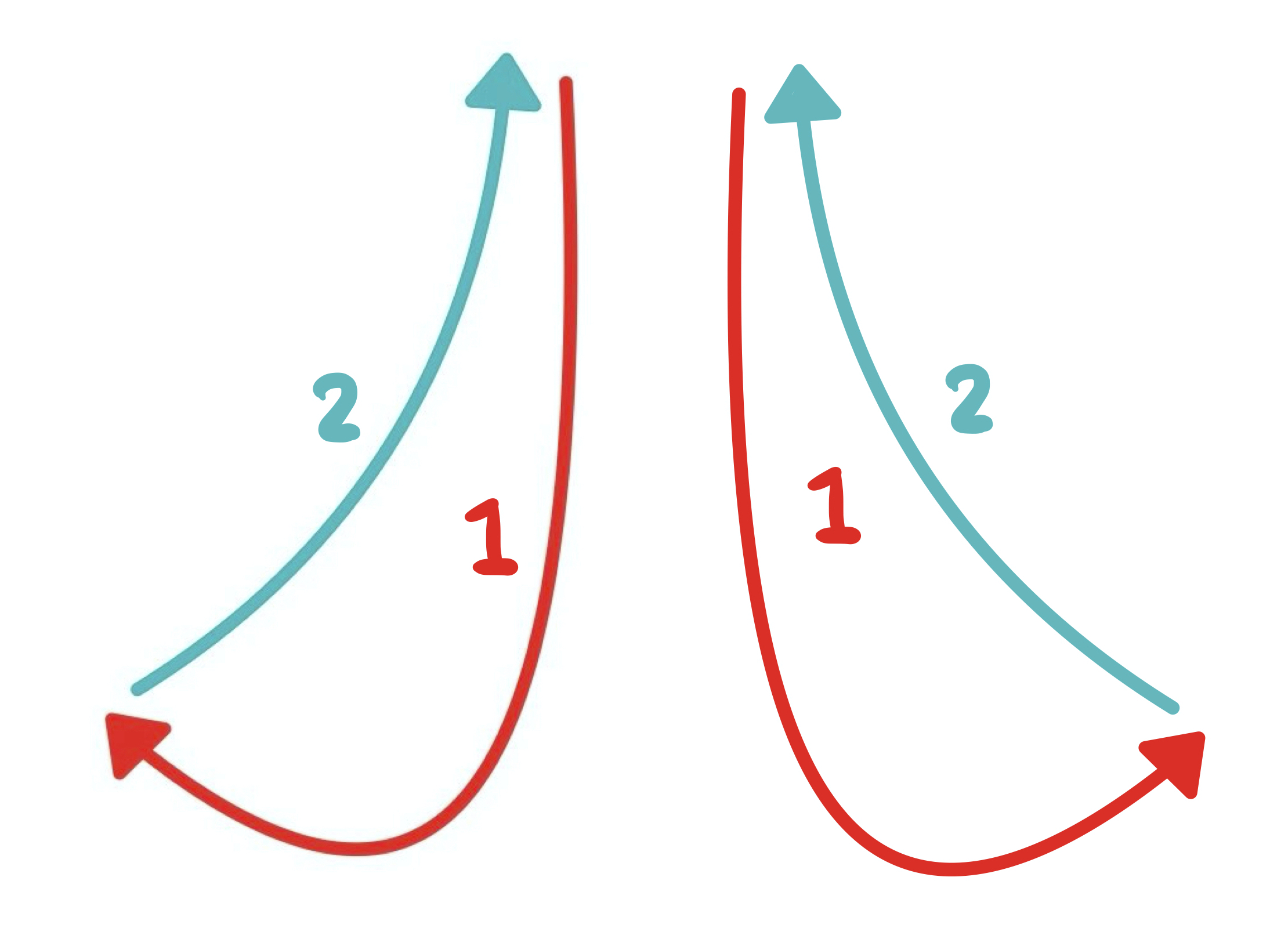

The simplest conducting pattern is for a two-beat measure, shown with a simple down-up pattern, typically inflected with a slight curve away from the body to look like a J (left arm) or backward J (right arm):

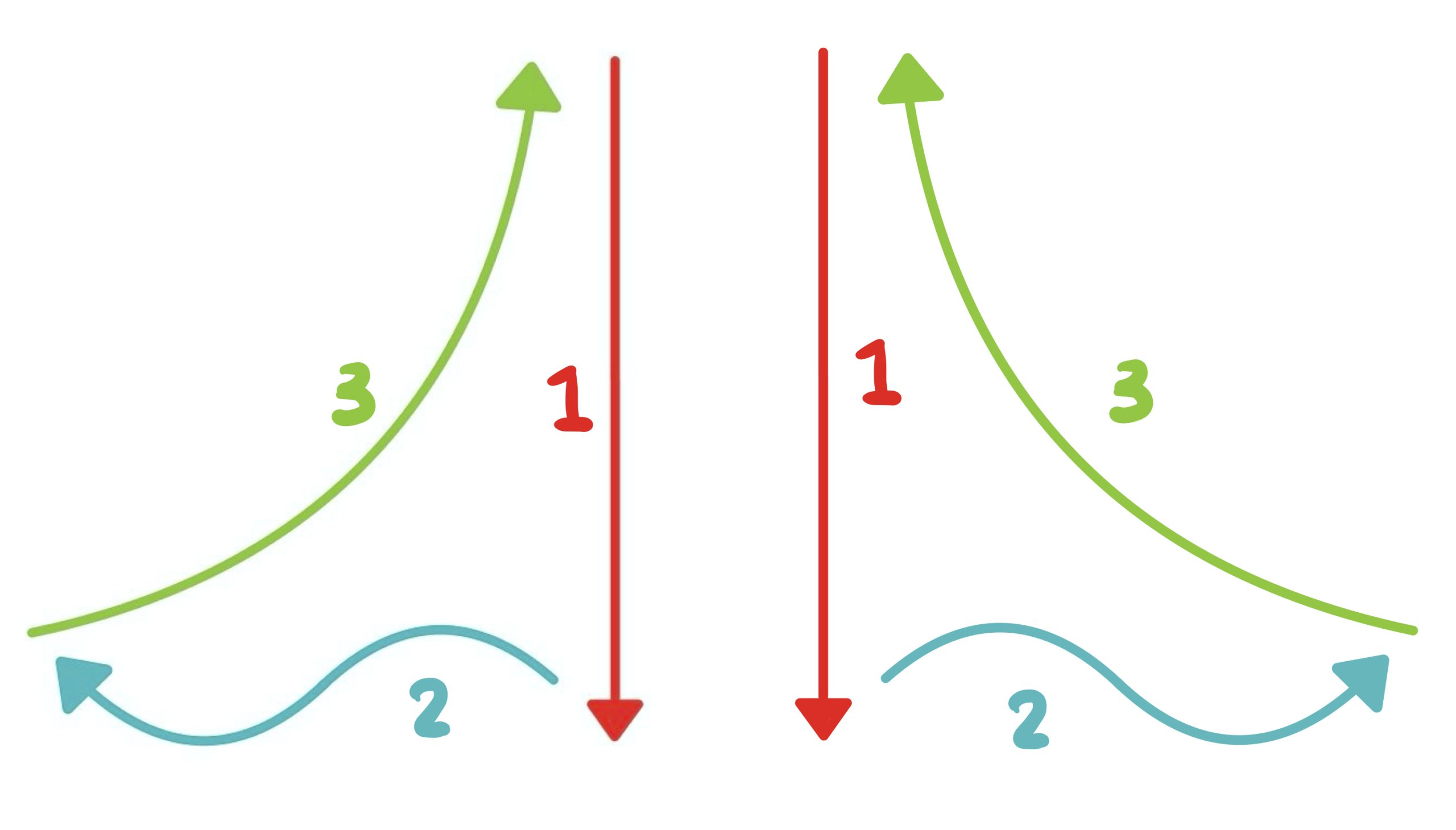

A three-beat measure is a down-out-back triangle:

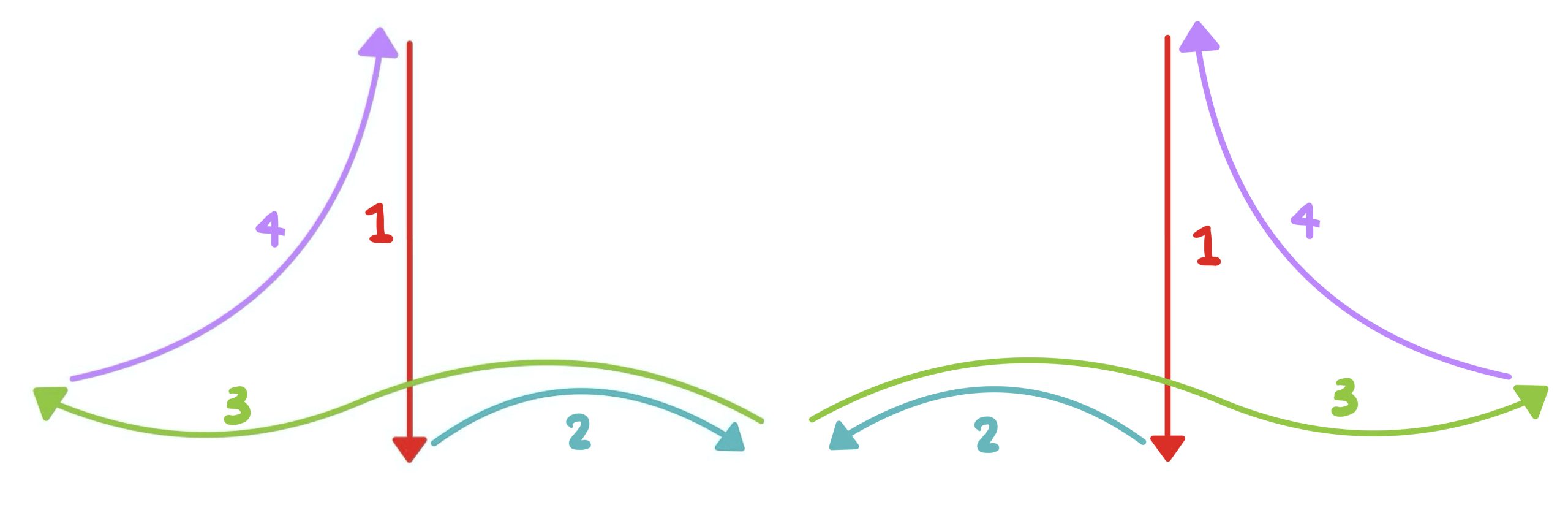

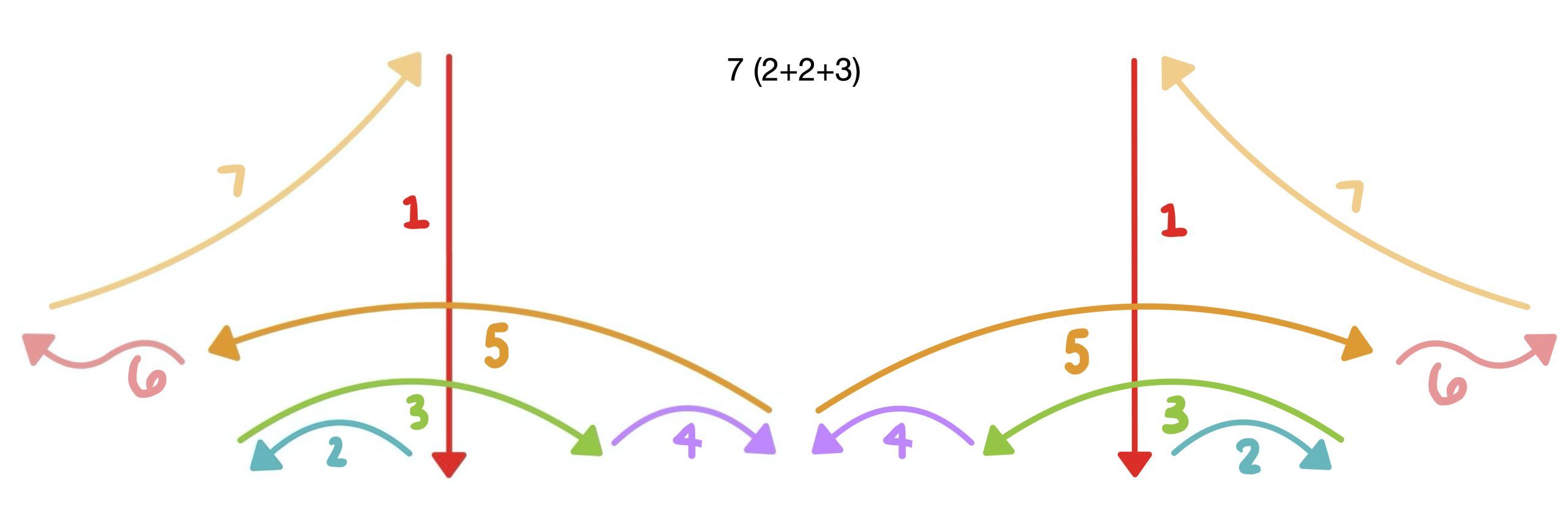

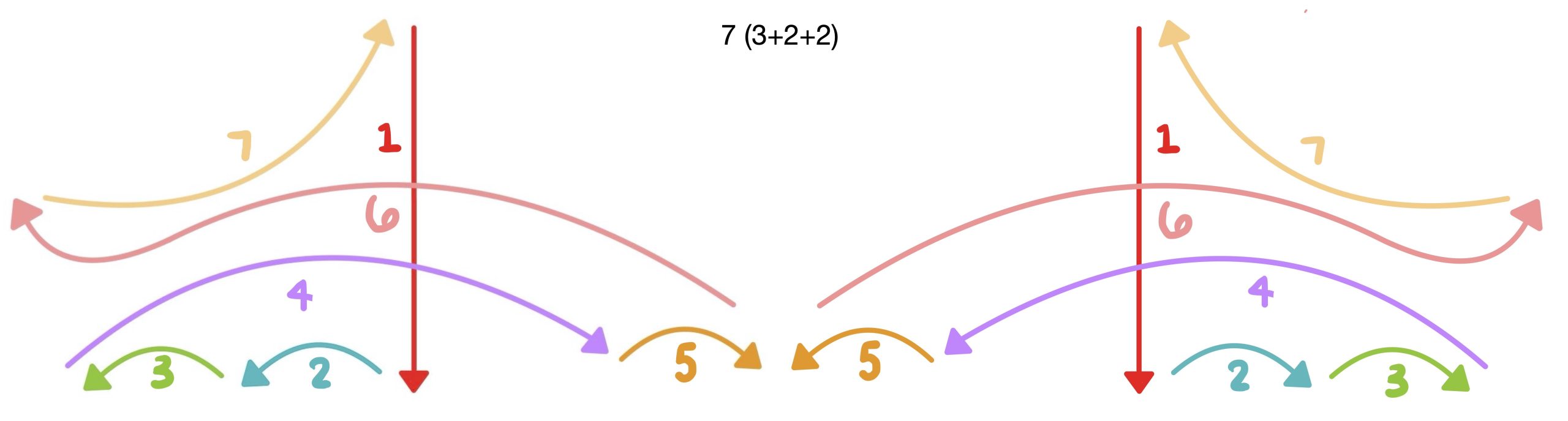

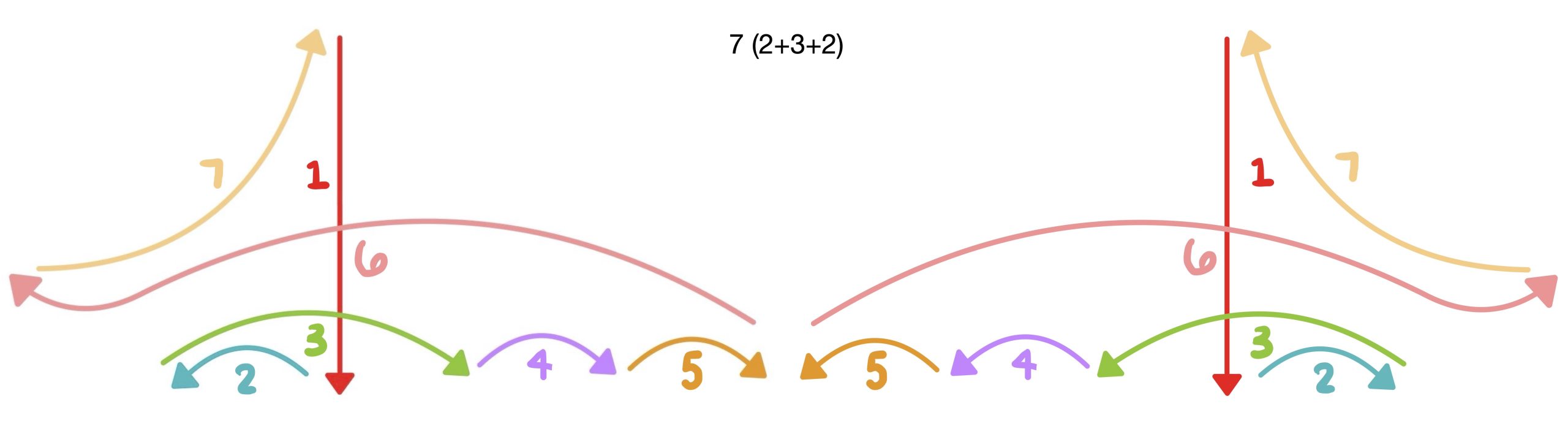

A four-beat measure (remember, this is often impossible to distinguish from a two-beat measure when listening, even though it has its own pattern) is down-in-out-back:

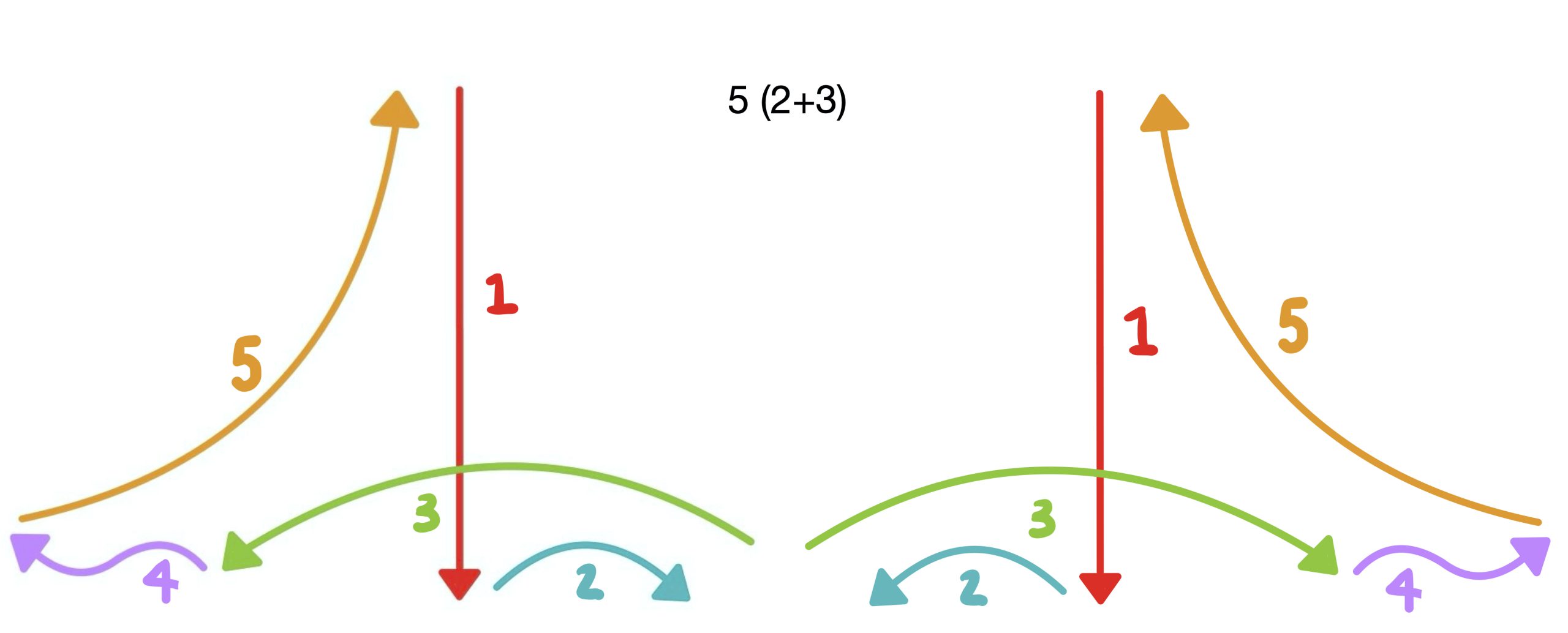

For additional beats (5, 6, 7, etc.), we simply add more “ins” or more “outs.” As a rule of thumb, we switch from “ins” to “outs” at the moment in the middle of the measure that feels most significant for communication.

It’s important to note, though, that if you’re working from time signatures, a 6, 9, or 12 on the top of a time signature most often does not indicate 6, 9, or 12 waves of the hand (beats), but rather 6, 9, or 12 beat divisions, and thus 2, 3, or 4 beats. (More on time signatures here.)

Activity: Practicing Conducting

Goal: Practice conducting 2, 3, and 4 patterns (and additional patterns as determined by your and your mentors’ goals) until they start to feel “natural.”

Instructions: Choose a tempo and a measure length (likely 2, 3, or 4 beats). Set a metronome at your chosen tempo and practice conducting along. Once you feel comfortable, choose a new tempo and measure length. Tempos between 60–120 beats per minute are likely to feel most comfortable.

Activity: Aligning Conducting with Music

Goal: Make connections between your embodied experience of conducting and sounding music.

Instructions: Listen to the songs below. Use movement to find an appropriate beat and measure, and determine the measure length. Conduct along using the appropriate conducting pattern. If you find this easy, see if you can jump right into conducting without thinking through beat and measure first, but be sure you have someone around who can help determine whether your choices work with the music. If you have difficulty following the measure, it may help to think explicitly about repeating patterns in the melody or accompaniment, chord changes, low notes (the bass), long notes in bass and melody, and (in music with text) stressed syllables.