There Was Surprisingly Little Knowledge of Neuroscience Gained in the 5000 Years from the Ancient Egyptians to the European Renaissance

Jim Hutchins

Objective 2: Explain the advances made in the understanding of neuroscience in the first 5000 years of recorded history.

History of Neuroscience Objective 2 Video Lecture

The reason we don’t know much about what Neolithic and Indigenous peoples knew of trepanning is that we don’t have any written record of their activities: the skulls are the only evidence they left. Some of the oldest European skulls date from 10,000 years ago (8000 BCE). Writing, on the other hand, started about 3400 BCE. The word “brain” started to appear in Egyptian hieroglyphics about 3000 BCE.

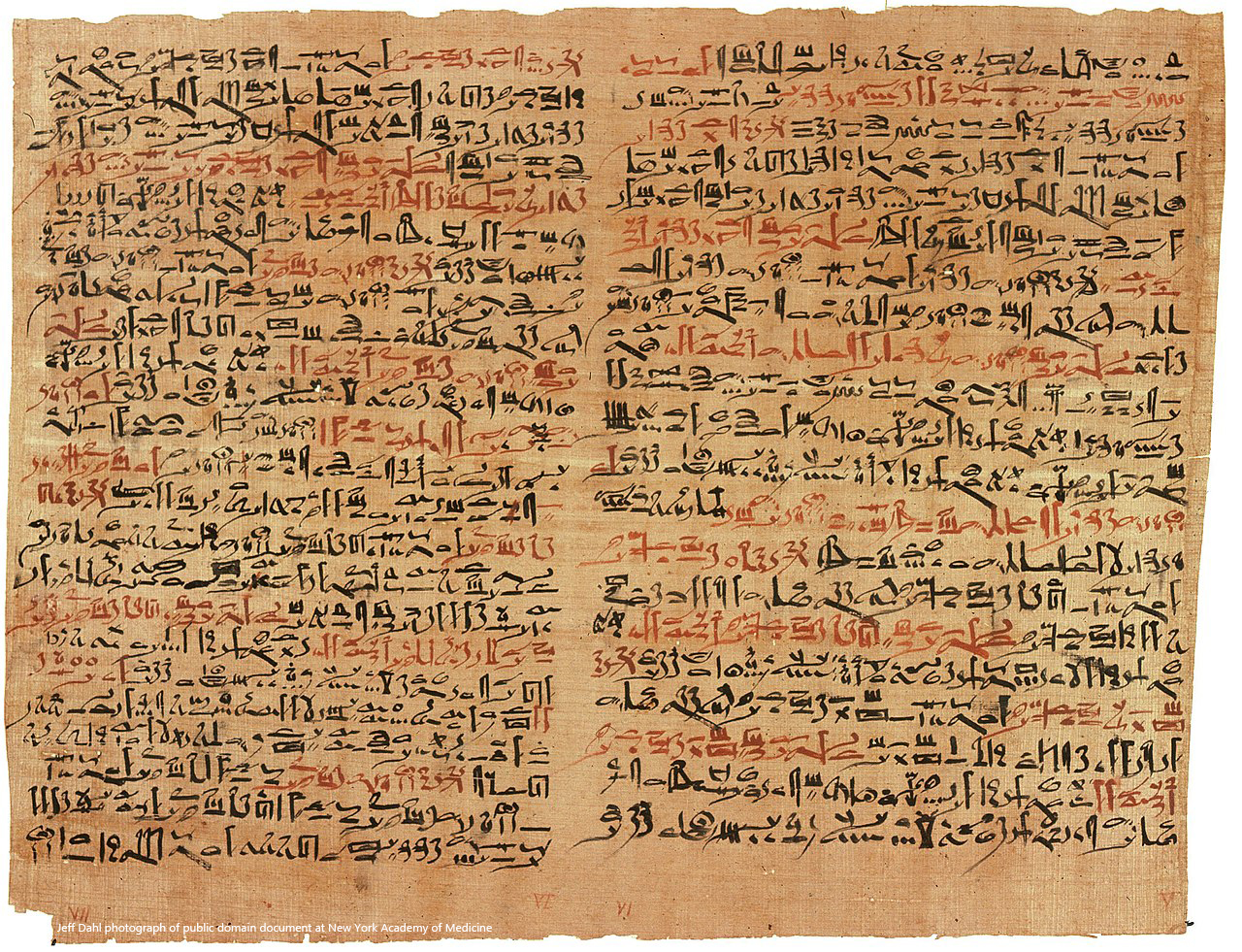

One key piece of evidence for an early system of neuroscience is the Edwin Smith surgical papyrus, dating from about 1700 BCE. In this record, an unnamed Egyptian physician is studying battle wounds to the head. He notes

- pulsations of the exposed brain

- the appearance of gyri (bumps) and sulci (grooves) on the brain

- “he speaks not to thee”

- “he shudders exceedingly” (probably a description of seizures from brain injury)

This knowledge of brain function was transferred from Egypt to Ancient Greece as knowledge and civilization shifted in the ancient Western world. Alcmeon of Croton[1], writing about 480 BCE, knew that the brain contained the “governing faculty”. Herophilus carried out dissections of the cerebrum and cerebellum about 300 BCE. The more famous Greek physician Galen followed his work some 500 years later. Erasistratus, working about the same time as Herophilus, performed experiments on the living brain.

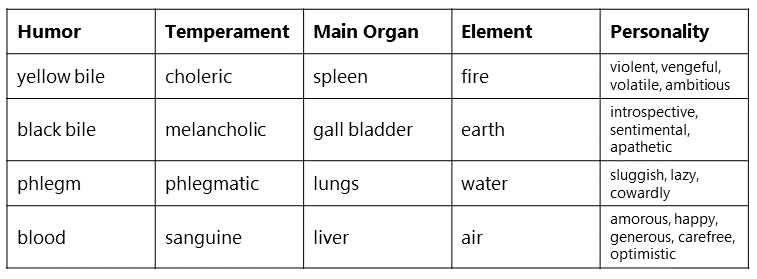

Unfortunately, as we will see occurring over and over, the Greeks’ understanding of neuroscience was limited by their models of natural philosophy. The Greeks believed that all bodily functions were controlled by bodily humors, a collection of four different kinds of liquid which were found in the human body. The Greeks called these choles. Not only are Shakespeare’s plays from c. 1600 CE imbued with this philosophy, but the English language still carries these ideas:

- melancholy describes an excess of black bile;

- cholera is a disease where patients make a lot of greenish liquid;

- a cholecystectomy is an operation where the gall bladder (–cyst– = fluid-filled sac; –ectomy = removal) is surgically separated from the body.

Hippocrates (460–379 BCE) believed that the seat of knowledge was the brain, while Aristotle (384–322 BCE), looking at the same evidence and writing around the same time, concluded the seat of knowledge is the heart, while the brain serves to cool the blood, a sort of radiator keeping the choles from getting too hot.

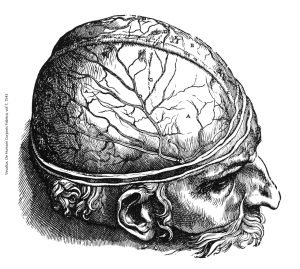

While Rome became the pre-eminent seat of learning and political power in the Common Era, the physician Galen (130–200 CE), born in modern Turkey, of Greek heritage, and a Roman citizen, carried on the Greek philosophical tradition. Like Herophilus, he dissected the brain. This led to his conclusions which illustrate another recurring theme in the history of neuroscience: getting the right answer for the wrong reasons. He concluded that the cerebrum is doughy, so it must store memories, while the cerebellum is hard, like a contracted muscle, so it must control the muscles. He was unable to get past the theory of bodily humors, so he believed the ventricles (fluid-filled spaces of the brain) were reservoirs for bodily humors.

The fall of Rome, the loss of the library at Alexandria, and the subsequent so-called Dark Ages froze Western civilization’s understanding of neuroscience in this state for 1500 years. But progress was still made in other places, and in some ways was more durable because it wasn’t limited by the Greek insistence on the theory of bodily humors. For example, Persian Hali Abbas (علی بن عباس مجوسی) translated Galen into Arabic for his illustrated medical textbook Kitab al-Maliki (Complete Book of the Medical Art). From this scholarly work, for example, we derived the modern terms dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater for the three layers of membranes covering the brain. (These are Latin words, translated poorly from the Arabic, as we will discuss elsewhere.)

Exploration and the invention of the printing press led to a political, religious, and social realignment known to the modern world as the Western Renaissance (a French word that means, literally, “re-birth”). Starting about 1420 CE, Portuguese explorers begin to sail the Atlantic Ocean, with the prevailing winds and currents leading them along the African coast and around the Cape of Good Hope to the south. As they began to venture further west, they ended up conquering indigenous tribes in what is now Brazil. Similarly, Spanish explorers ended up further north. (These discoveries are reflected in the languages spoken in different parts of the so-called New World.) About the same time, in Germany, Johannes Gutenburg invented the printing press (c 1440 CE), which freed written records from having to be copied in monasteries and made learning to read accessible to the common man.

Anatomical knowledge could now be transmitted more easily from teacher to student and from culture to culture, and Western human understanding of anatomy blossomed as a result. For example, the great Flemish anatomist Vesalius (c 1540 CE), through his incredible artistic skill, both increased our anatomical vocabulary and our anatomical knowledge.

Anatomical knowledge could now be transmitted more easily from teacher to student and from culture to culture, and Western human understanding of anatomy blossomed as a result. For example, the great Flemish anatomist Vesalius (c 1540 CE), through his incredible artistic skill, both increased our anatomical vocabulary and our anatomical knowledge.

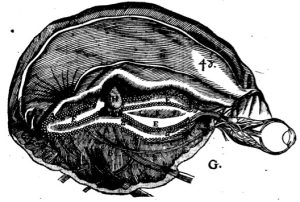

The highly-touted Scientific Method, which is taught to every child in school, was still in its rudimentary stages and was still (as now) limited by technology and pre-conceptions. For example, René Descartes (1596-1650 CE), perhaps the most brilliant natural philosopher of the 17th century, was still forced by the theology of the time to propose a system based on Greek humors that maintained a separation between the mind (or soul) and the body (or brain substance). The French elites of Descartes’ time were enamored of statuary that operated on the principle of hydraulics (moving water under different pressures). So of course it was obvious that when the foot is exposed to a fire, there must be movement of fluid in a series of channels which then end up causing the brain to send fluid back down to the muscles, completing a reflex arc.

The highly-touted Scientific Method, which is taught to every child in school, was still in its rudimentary stages and was still (as now) limited by technology and pre-conceptions. For example, René Descartes (1596-1650 CE), perhaps the most brilliant natural philosopher of the 17th century, was still forced by the theology of the time to propose a system based on Greek humors that maintained a separation between the mind (or soul) and the body (or brain substance). The French elites of Descartes’ time were enamored of statuary that operated on the principle of hydraulics (moving water under different pressures). So of course it was obvious that when the foot is exposed to a fire, there must be movement of fluid in a series of channels which then end up causing the brain to send fluid back down to the muscles, completing a reflex arc.

Descartes believed that the pineal gland, deep inside the brain, was the master bladder of the hydraulic system and therefore the seat of the soul.

Descartes believed that the pineal gland, deep inside the brain, was the master bladder of the hydraulic system and therefore the seat of the soul.

Another example of this misuse of the scientific method was the subject of historian Holly Tucker’s excellent book Blood Work, a true story in which the French physician Jean-Baptiste Denis decides to treat a “hot-blooded” (probably mentally ill) Parisian man by infusing him with sheep’s blood, which will make him docile, like a sheep, when his bodily humors are replaced with the sheep’s. Although this victim survived, many others did not, and the procedure was eventually abandoned. It would be more than 230 years later before Karl Landsteiner, working at the University of Vienna, discovered human blood types and made the transfusion of blood possible. The whole episode is a case study in the brutal and deadly misuse of the scientific method.

On a more lighthearted note, the “she’s a witch, burn her!” scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail covers most of the essential features of what was wrong with the scientific method in the Middle Ages. (Note the events and dialog at the very end of the scene: they got the right answer, but for all the wrong reasons.)

A breakthrough in our understanding of neuroscience came from a surprising source: one of the founding fathers of the United States of America, Benjamin Franklin. Franklin, in addition to inventing the $100 bill (#dadjoke), was a scientist who experimented with electricity. He wrote a pamphlet on electricity in 1751 CE which changed the thinking of physiologists from bodily humors to electricity as the essential feature of the nervous system.

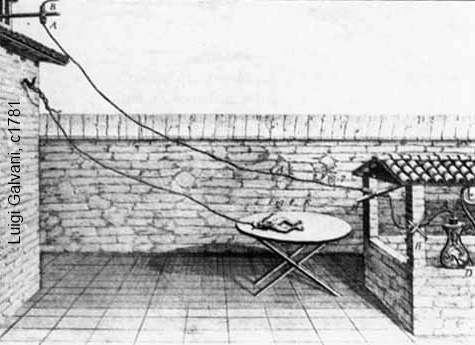

In 1781, Italian physiologist Luigi Galvani tried a novel experiment. He set up an apparatus to store electricity (a Leyden jar) and then connected the Leyden jar to a frog’s leg muscle with a metal object such as a scalpel. The frog’s leg jumped! Galvani proposed a concept which was at least partly correct: that there was an “animal electricity” that drove the functions of the nervous system. (As an aside, the procedure of galvanizing metal by electrifying it and putting it a metallic ion bath is called galvanization in his honor.) Galvani published his findings in a monograph titled “De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari Commentarius” (“Commentary on the Effect of Electricity on Muscular Motion”). Galvani was opposed by fellow Italian Alessandro Volta (from whose name we get the electrical unit of volts). Volta believed that animal electricity was the same as “metallic electricity”, as he called it, and he was right about this. It was some time before these concepts came together, but we will discuss how that works in another section of the book.

In 1781, Italian physiologist Luigi Galvani tried a novel experiment. He set up an apparatus to store electricity (a Leyden jar) and then connected the Leyden jar to a frog’s leg muscle with a metal object such as a scalpel. The frog’s leg jumped! Galvani proposed a concept which was at least partly correct: that there was an “animal electricity” that drove the functions of the nervous system. (As an aside, the procedure of galvanizing metal by electrifying it and putting it a metallic ion bath is called galvanization in his honor.) Galvani published his findings in a monograph titled “De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari Commentarius” (“Commentary on the Effect of Electricity on Muscular Motion”). Galvani was opposed by fellow Italian Alessandro Volta (from whose name we get the electrical unit of volts). Volta believed that animal electricity was the same as “metallic electricity”, as he called it, and he was right about this. It was some time before these concepts came together, but we will discuss how that works in another section of the book.

To summarize, then, by the end of the 17th century, we knew these things as a foundation for neuroscience:

- we had completed brain dissections and identified major regions of the brain

- we had described white matter vs gray matter functions

- we knew that nerves act like wires to conduct electricity

- we knew the brain has lobes, gyri (bumps), and sulci (grooves)

- we knew there is a central nervous system and a peripheral nervous system

- we discovered injury to the brain disrupts sensations, movement, and thought, and can even cause death

- we knew different parts of the brain probably do different things

- we finally accepted that the brain is a machine which follows natural laws

Media Attributions

- Edwin Smith Papyrus © Jeff Dahl is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Greek humors table © Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Sheep Brain Dissection © aaronbflickr is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Vesalius 1543 © Encephalon~commonswiki is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Descartes reflex © Wellcome Collection is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Descartes pineal gland © Wellcome Collection is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Galvani frog legs © Luigi Galvani is licensed under a Public Domain license

- These names almost sound like something from a comedy sketch, and even though they don't roll off the English-speaking tongue, they sure sound good for dinner party conversation. ↵