The Thalamus and Hypothalamus

Jim Hutchins

Objective 5: Name the key regions of the thalamus and hypothalamus.

Important Locations Objective 5 Video Lecture

Thalamus

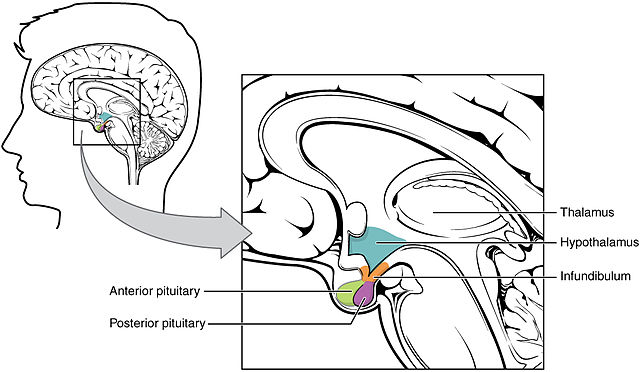

The word thalamus was named by the neuroscientists of the Enlightenment and refers to the Latin word for “inner chamber” or “bedroom” with the additional implication of the marriage bed. Even though they were naming parts of the brain based on appearance, by lucky accident the thalamus and (just underneath it) the hypothalamus were appropriately named. The thalamus is the place where our innermost thoughts either flower in the cerebral cortex (because cortex = consciousness), or are stopped before they can become conscious thoughts. Conscious movement is shaped and smoothed by motor circuits running through the thalamus. Almost all homeostatic loops, the circuitry and chemistry that keeps the body’s systems in balance, are routed through the hypothalamus. In fact, while you might have been taught as a child that the pituitary is the “master gland” of the human body, the pituitary has a master — the hypothalamus. (Who is the hypothalamus’ master? Well, a committee, of course.)

The word thalamus was named by the neuroscientists of the Enlightenment and refers to the Latin word for “inner chamber” or “bedroom” with the additional implication of the marriage bed. Even though they were naming parts of the brain based on appearance, by lucky accident the thalamus and (just underneath it) the hypothalamus were appropriately named. The thalamus is the place where our innermost thoughts either flower in the cerebral cortex (because cortex = consciousness), or are stopped before they can become conscious thoughts. Conscious movement is shaped and smoothed by motor circuits running through the thalamus. Almost all homeostatic loops, the circuitry and chemistry that keeps the body’s systems in balance, are routed through the hypothalamus. In fact, while you might have been taught as a child that the pituitary is the “master gland” of the human body, the pituitary has a master — the hypothalamus. (Who is the hypothalamus’ master? Well, a committee, of course.)

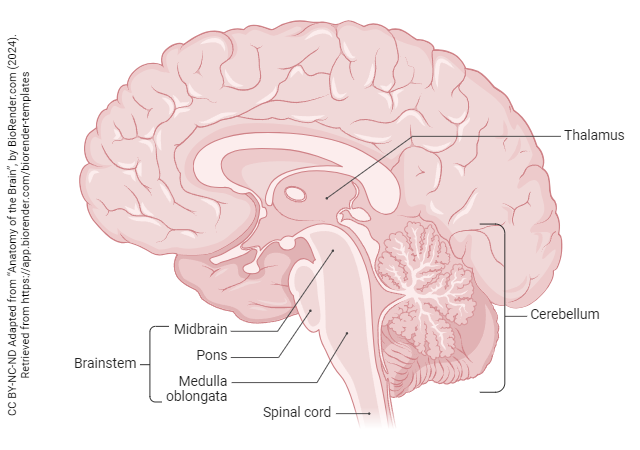

Some authorities include the thalamus as part of the brainstem; others consider the thalamus to sit atop the brainstem. Either way, the thalamus is an area that relays information going up to cortex, and relays information leaving cortex on its way to the brainstem or spinal cord.

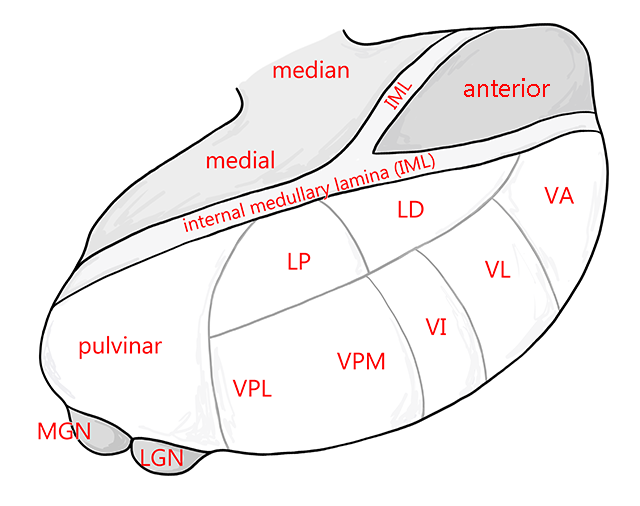

The thalamus can be divided into several functional regions, generally named by their position (lateral or medial; ventral or dorsal; posterior or anterior) in various combinations.

For example, when we study the somatosensory system we will see that the ventral posterior (VP) region of the thalamus relays somatosensory information from lower processing levels to the somatosensory cortex. The body is represented in the ventral posterolateral (VPL) thalamus in a somatotopic arrangement (i.e. mapped by body location, from upper extremity more medially to lower extremity more laterally). The face is represented in the ventral posteromedial (VPM) thalamus.

For example, when we study the somatosensory system we will see that the ventral posterior (VP) region of the thalamus relays somatosensory information from lower processing levels to the somatosensory cortex. The body is represented in the ventral posterolateral (VPL) thalamus in a somatotopic arrangement (i.e. mapped by body location, from upper extremity more medially to lower extremity more laterally). The face is represented in the ventral posteromedial (VPM) thalamus.

The basal nuclei are relayed through the ventral anterior (VA) and ventral lateral (VL) thalamus. From there, information flows to premotor cortex (Brodmann 6).

Visual stimuli are relayed through the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), also called the lateral geniculate body, to visual cortex.

Auditory stimuli are relayed through the medial geniculate nucleus (MGN), also called the medial geniculate body, to auditory cortex.

Hypothalamus

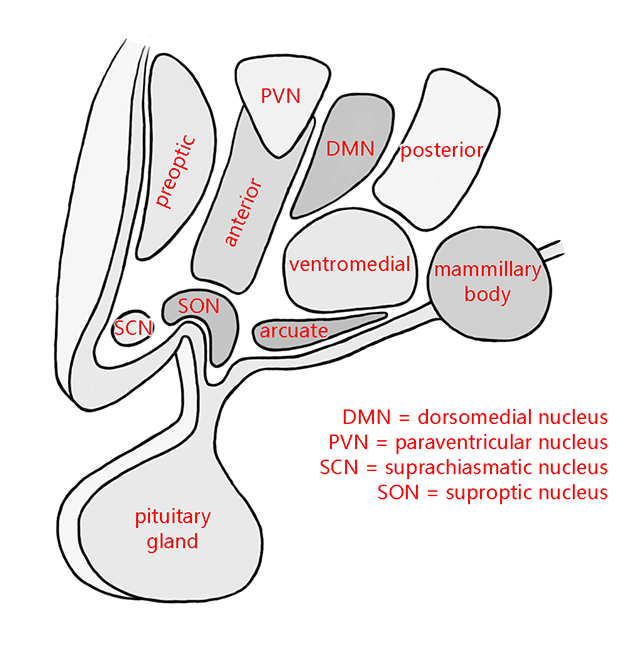

Similarly, there are regions of the hypothalamus devoted to specific functions. For example, cells in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and supraoptic nucleus (SON) send axons to the posterior pituitary, where they release the hormones oxytocin and antidiuretic hormone (ADH, also called vasopressin).

The interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus 3 (INAH-3), despite its unassuming name, appears to play a major role in expression of gender and sexuality. It’s so minor it’s not even shown on this diagram.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus plays a major role in the regulation of circadian rhythms. It sits just above the optic chiasm (hence its name) and receives a small proportion of the visual information flowing out of the eye, which allows it to determine light-dark cycles.

Food intake is regulated by the ventromedial, dorsomedial, paraventricular, and lateral hypothalamic nuclei.

Media Attributions

- Sunflower thalamus © Saranyamuthu13 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Anatomy of the Brain © BioRender adapted by Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Thalamic egg all nuclei © Avalon Marker and Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Hypothalamus Pituitary Complex © Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H. Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark & DeSaix, Peter is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Hypothalamus all nuclei © Avalon Marker and Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license