The Gyrencephalic Brain: Gyri and Functional Areas

Jim Hutchins

Objective 3: Label the major gyri and functional areas of the cerebral cortex.

Important Locations Objective 3 Video Lecture

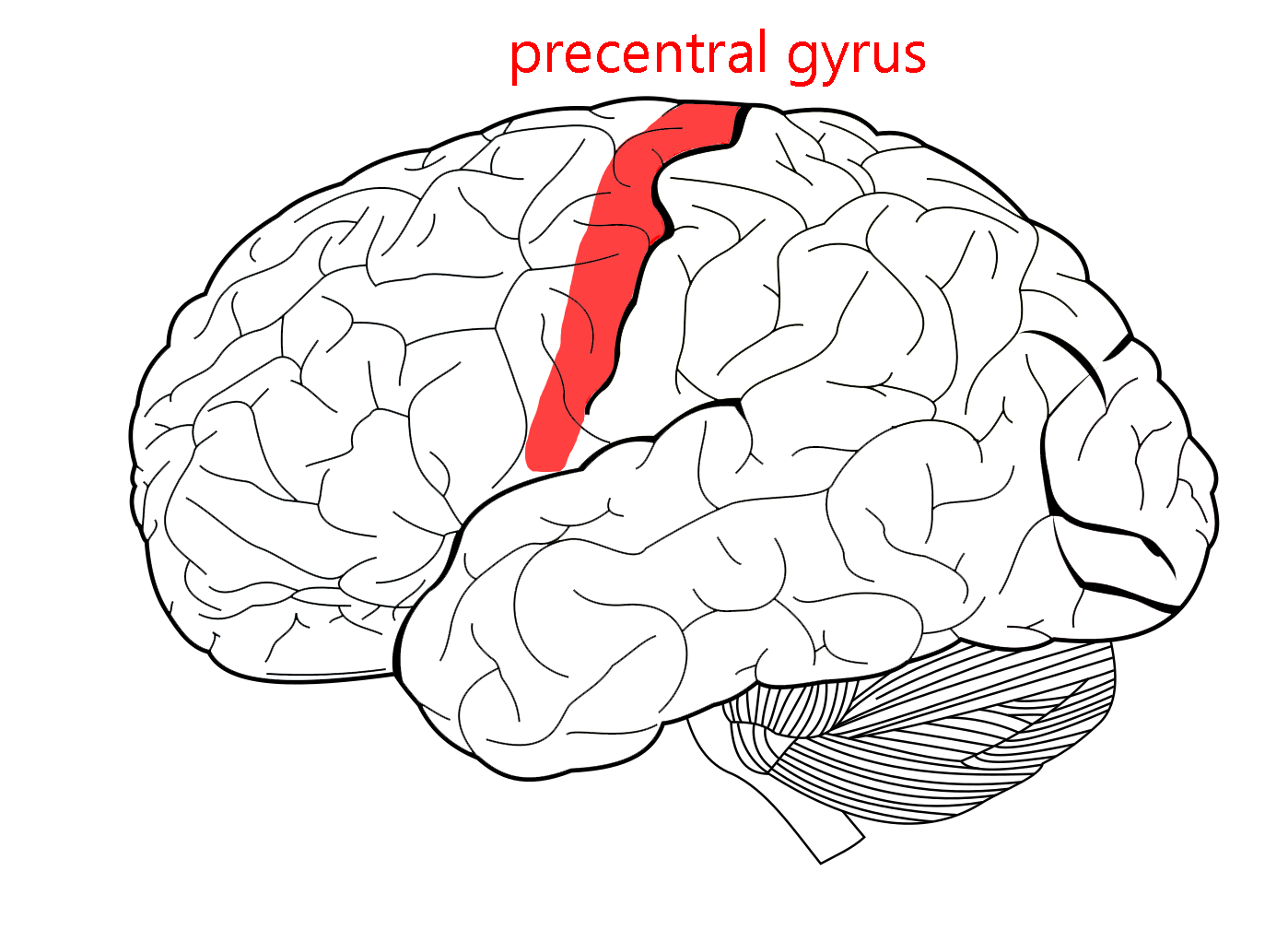

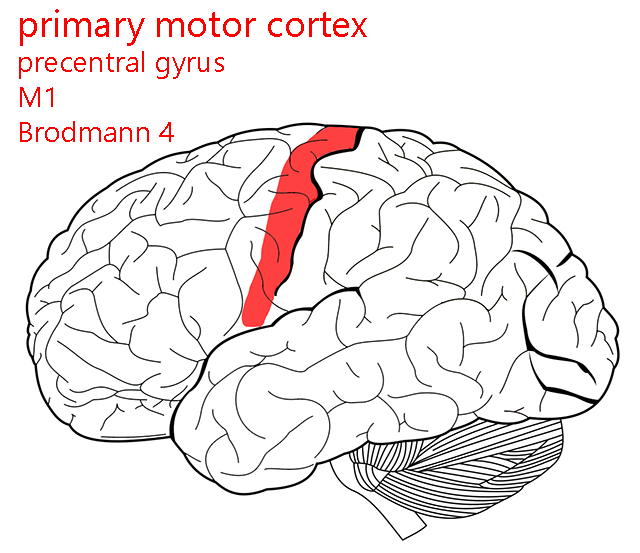

On either side of the central sulcus are two parallel, almost identical-looking gyri. The first we’ll look at is the precentral gyrus (part of the frontal lobe). The precentral gyrus is involved in the motor system, which has an orderly map of the body distributed across the surface of the gyrus. If you make a conscious movement, the signal needed for each muscle is calculated in this area and then sent as a neural signal down to the α motor neuron in the anterior horn of the spinal cord. Because this pathway goes from cortex to spinal cord, it’s called the corticospinal tract.

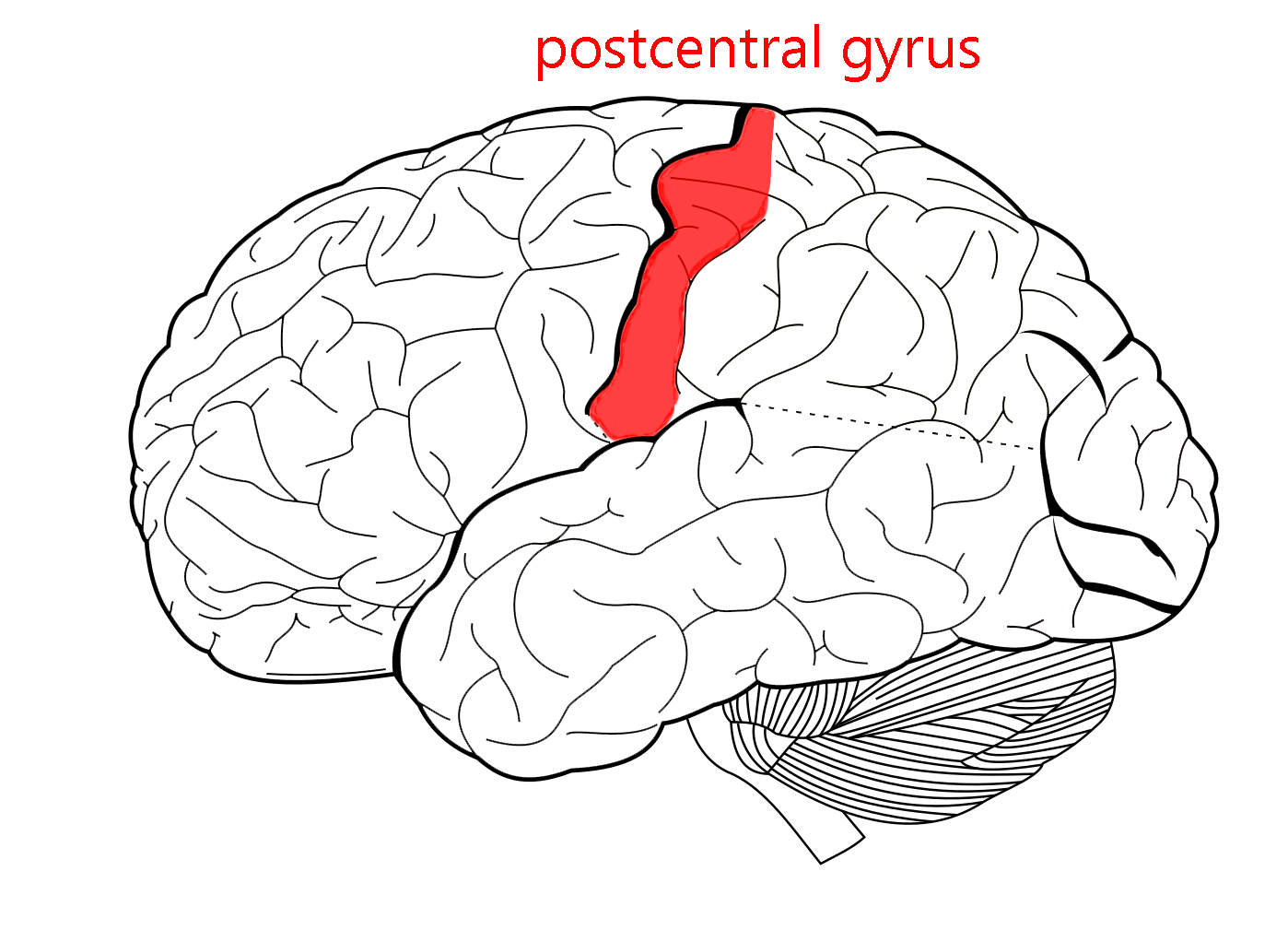

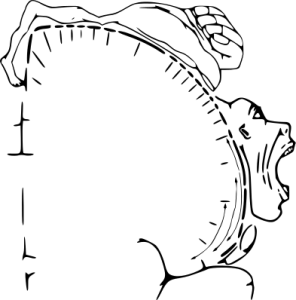

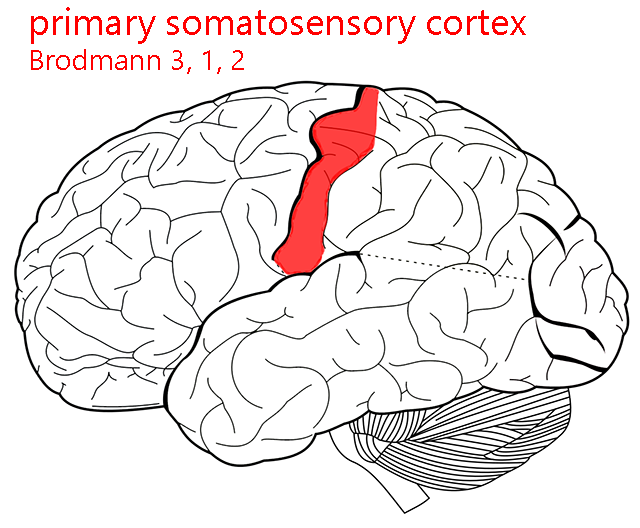

The postcentral gyrus processes sensations from the face and body surface (the somatosensory system). Like the motor cortex, it has an orderly map (homunculus) which is shown here.

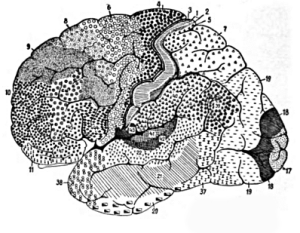

Returning to the cerebral cortex, now that we have some landmarks and lobes in mind, we can begin to further subdivide the cortex. The most common mapping system for the cortex was developed by Korbinian Brodmann in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

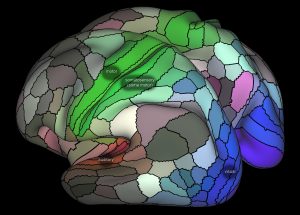

Brodmann was a German scientist who started slicing a brain and looking at the sections through a microscope. It’s surprising, as shown in the multicolored map developed in 2016 by Glasser and van Essen, how much modern maps resemble the classic map of Brodmann.

slicing a brain and looking at the sections through a microscope. It’s surprising, as shown in the multicolored map developed in 2016 by Glasser and van Essen, how much modern maps resemble the classic map of Brodmann.

For no reason that we can fathom, Brodmann started at the top and cut horizontal sections. Most of the cerebral cortex has six layers of cells, but the way the cells are packed and the shape of the cells are different in different places. The first pattern of cell shapes and packing he named Area 1; the second, Area 2; and so forth. The last area he numbered was Area 52.2

Some of the areas are synonymous with functional areas of the cortex and are still used today; others are obscure. Some of the area numbers you will frequently encounter are listed.

Parietal Lobe

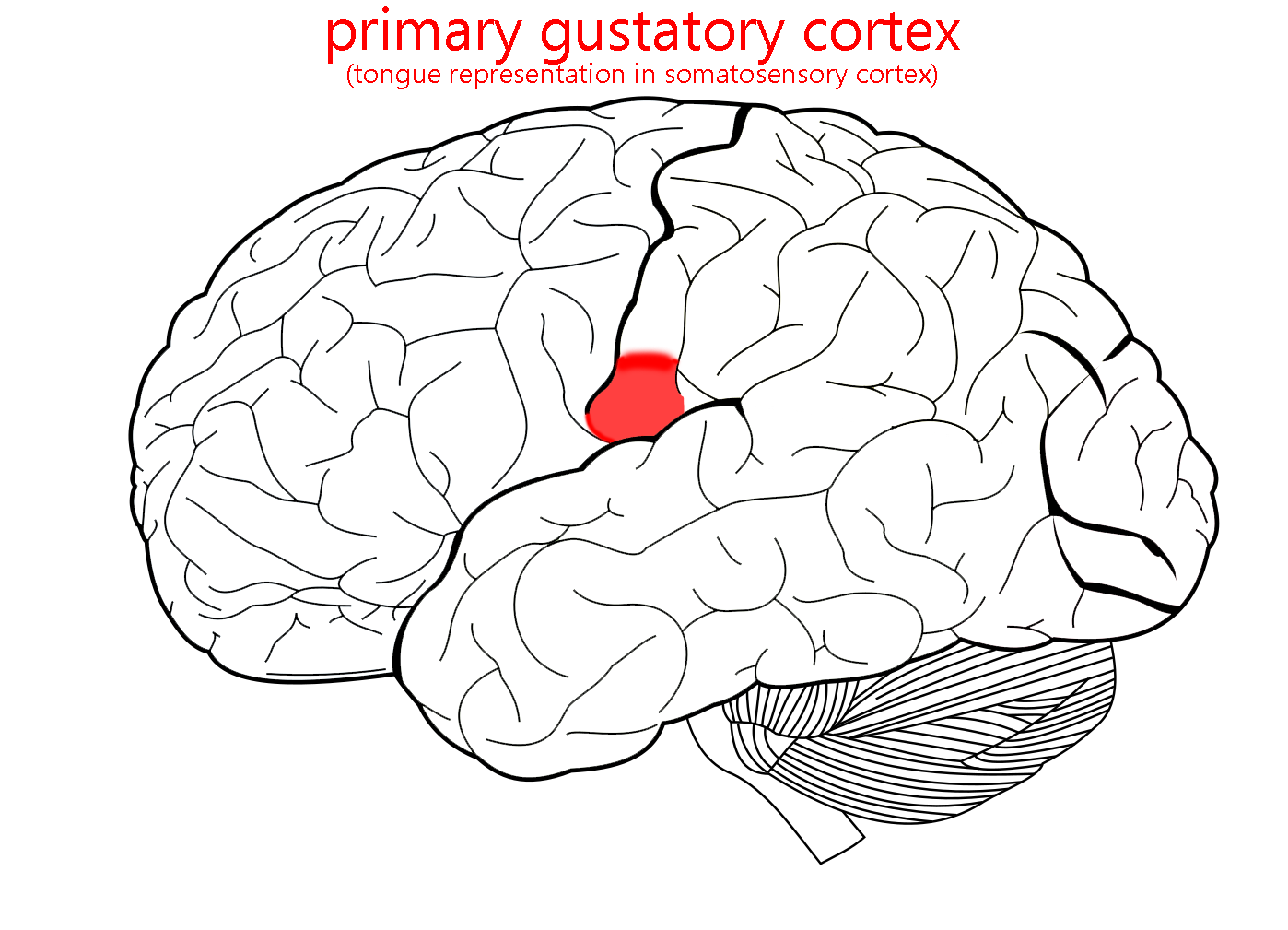

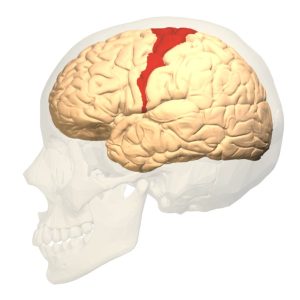

Areas 3, 1, and 2 (postcentral gyrus): primary somatosensory cortex, receiving information about the face and body surface. No one knows why we list them in this order. Taste is also here, and nearby in area 43.

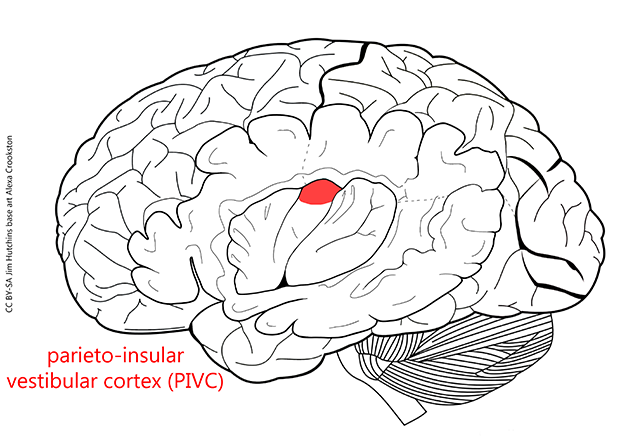

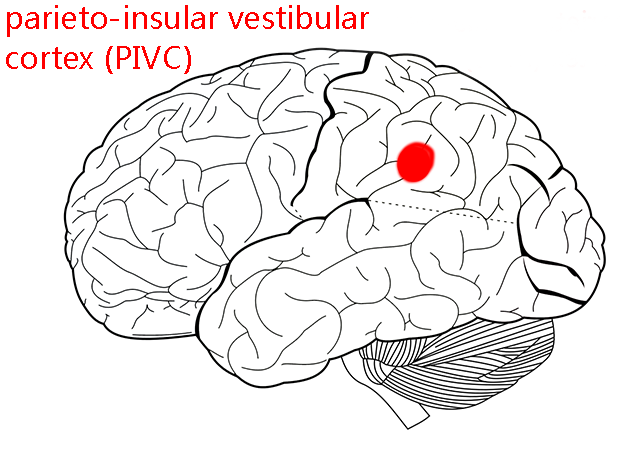

The parieto-insular vestibular cortex (PIVC) is a key cortical processing area for conscious vestibular sensations. It is found on the lateral surface of the brain in the parietal lobe, and it extends into the insula as shown here.

Frontal Lobe

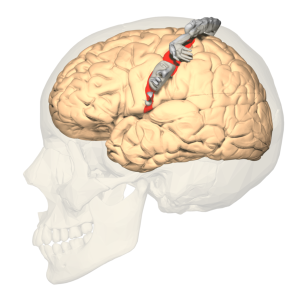

Area 4: (precentral gyrus): primary motor cortex, sending axons to the α motor neurons of spinal cord (executing movement). This is shown in the red shading in the illustration above.

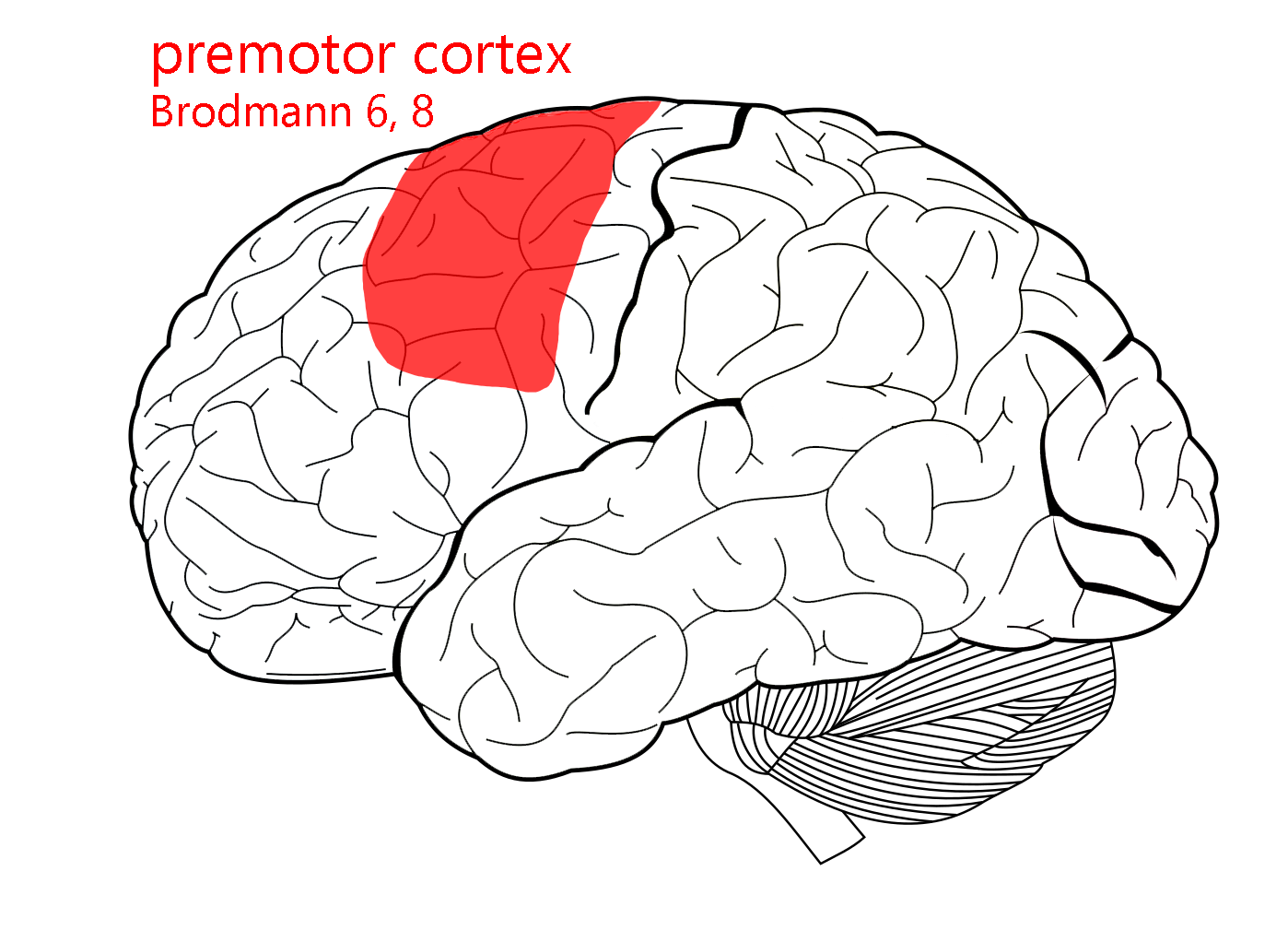

Area 6: supplementary motor area (planning or imagining movement).

Area 8: frontal eye fields (eye movements).

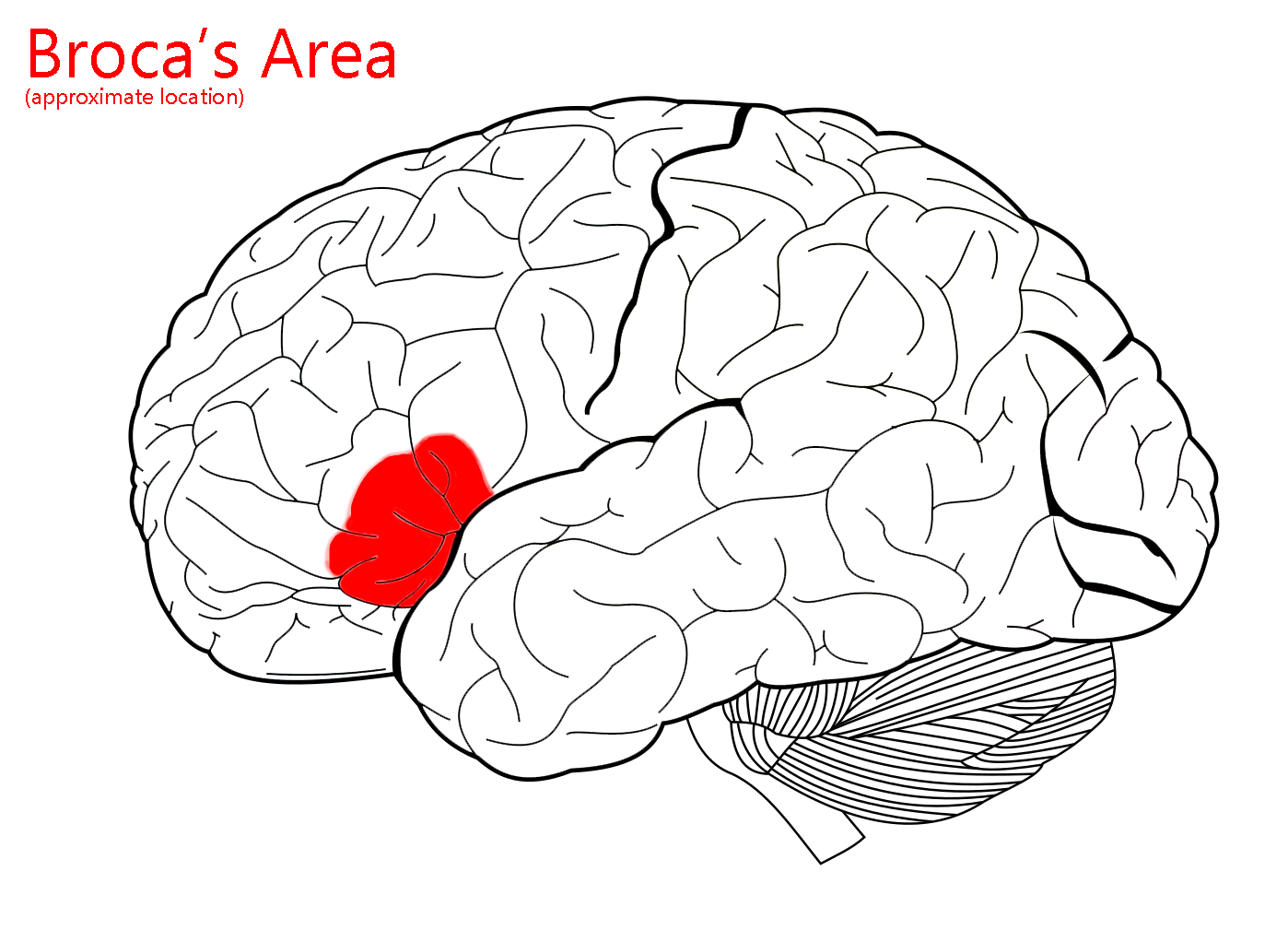

Areas 44 and 45: Broca’s area. In most people, Broca’s area on the left side is responsible for the production of speech (movements of the throat and tongue).

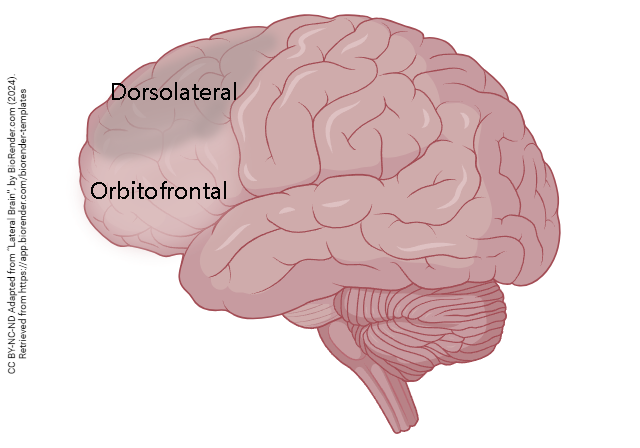

The non-motor areas of frontal cortex, in the rostralmost part of this large cortical lobe, are called prefrontal cortex. Prefrontal cortex is important for holding on to our personality and individuality, the things that make you “you”.

The non-motor areas of frontal cortex, in the rostralmost part of this large cortical lobe, are called prefrontal cortex. Prefrontal cortex is important for holding on to our personality and individuality, the things that make you “you”.

Among the important programs stored here are toilet training and social graces.

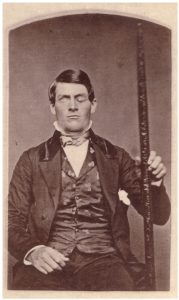

The story of how we discovered the importance of prefrontal cortex is both fascinating and horrifying. In 1848, a railroad construction foreman named Phineas Gage suffered a terrible accident: a pointed steel rod, about 4 feet long and 1 ¼ inch diameter, was blown through his left cheek and out the top of his head, obliterating his left eye and a good chunk of prefrontal cortex in the process. Miraculously, Gage survived. However, his personality changed and he was no longer much fun to be around. In essence, he lost his kindergarten training. This was the first indication that specific functions, in this case personality, could reside in specific areas of the brain. When we talk about motor cortex, or visual cortex, or auditory cortex, as we have above, it’s because Gage’s accident pointed the way to our conception of the brain as made up of a cluster of semi-independent modules each performing a specific function. This view has been validated by neurological studies (for example in stroke) that have been carried out in the almost 200 years since his accident. Some medical pioneers had no choice in the matter.

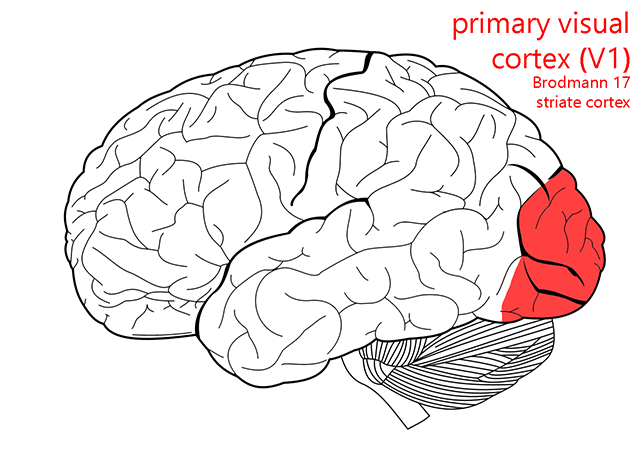

Occipital Lobe

Areas 17, 18 and 19: Visual cortex (sensory, sight). Area 17 is also called primary visual cortex (V1) or striate cortex.

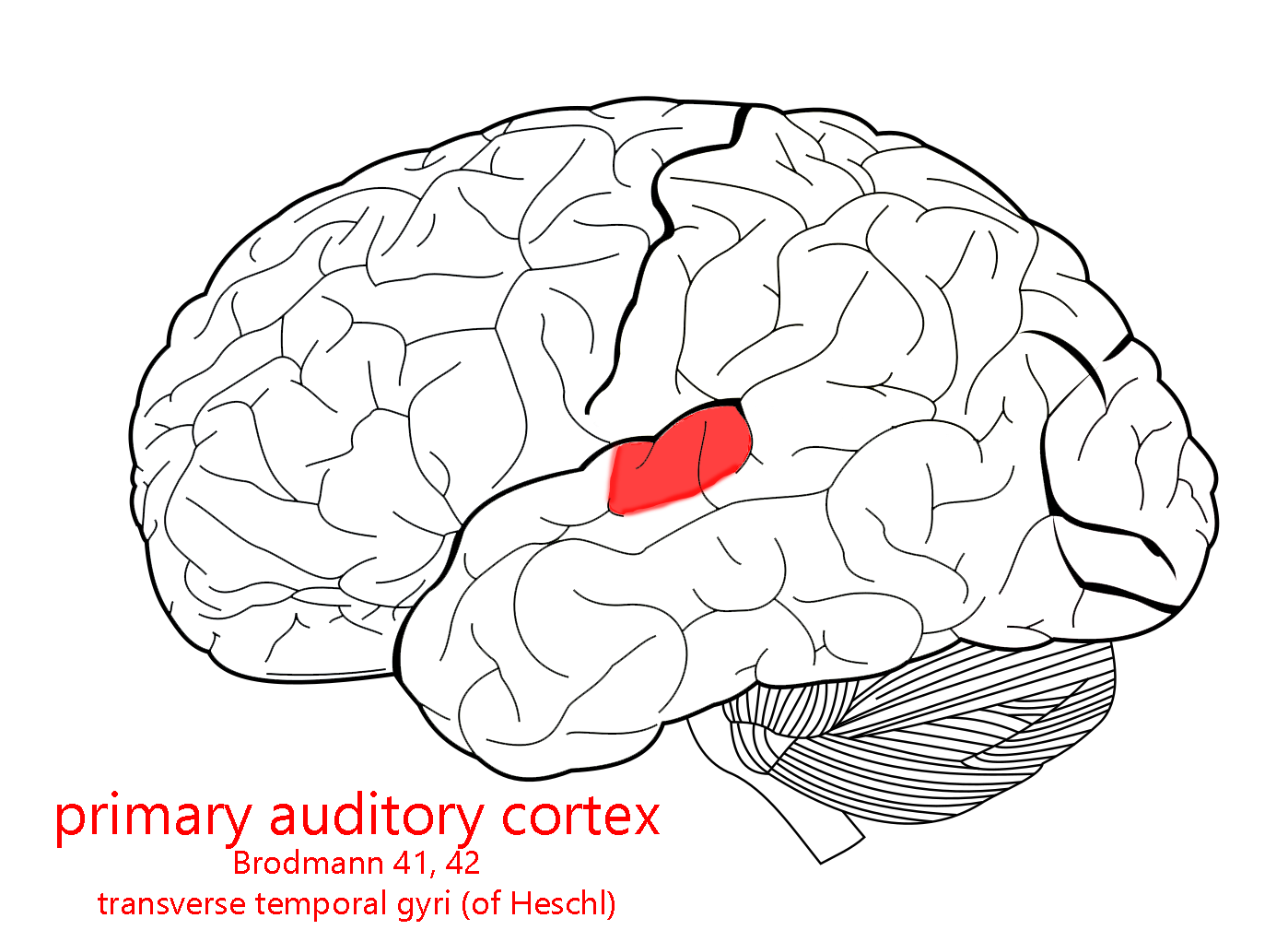

Temporal Lobe

Areas 41 and 42: Primary auditory cortex (sensory, hearing).

Areas 41 and 42: Primary auditory cortex (sensory, hearing).

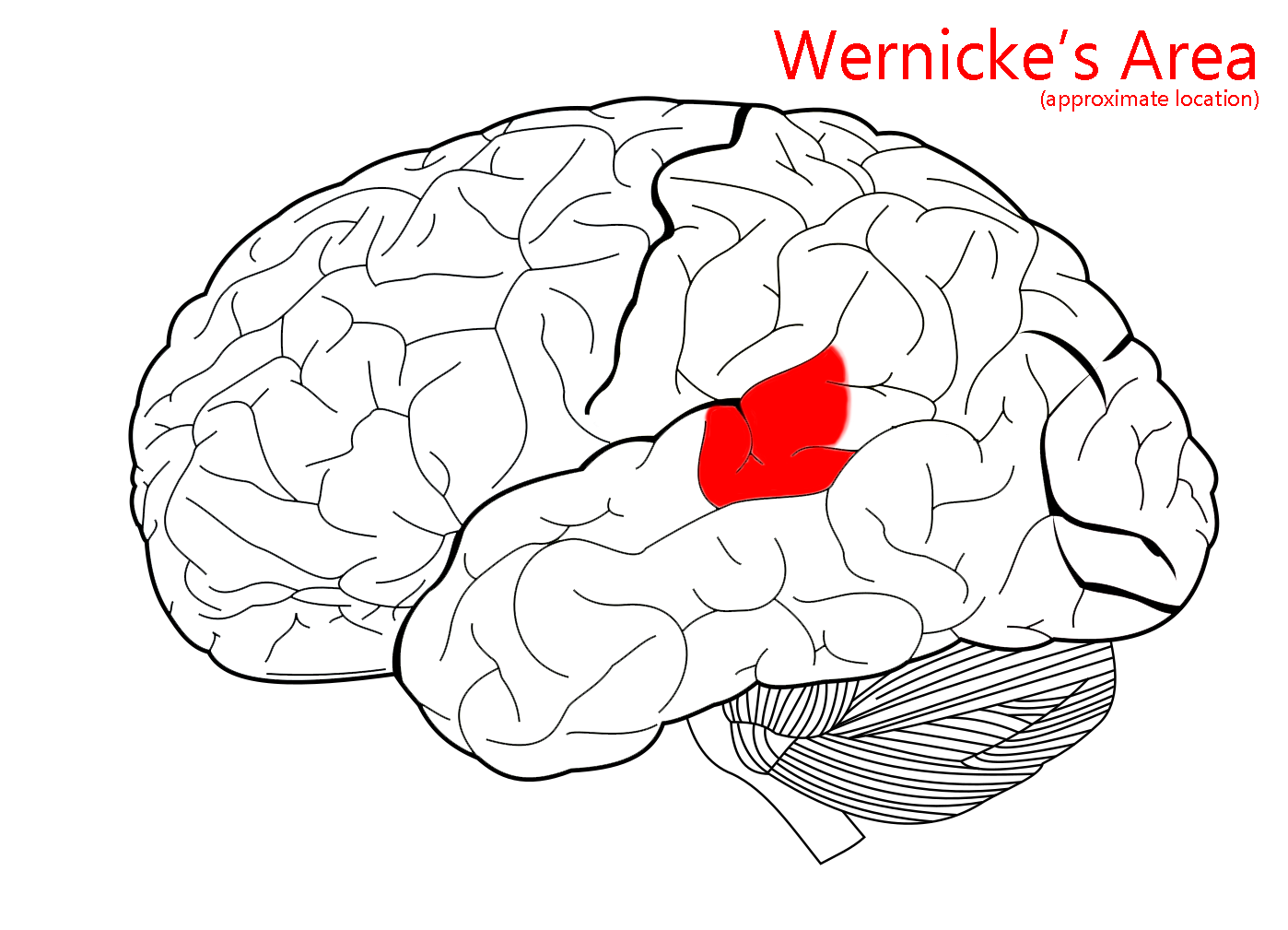

Area 22p (posterior part of 22): Wernicke’s area. Responsible for the understanding of speech sounds.

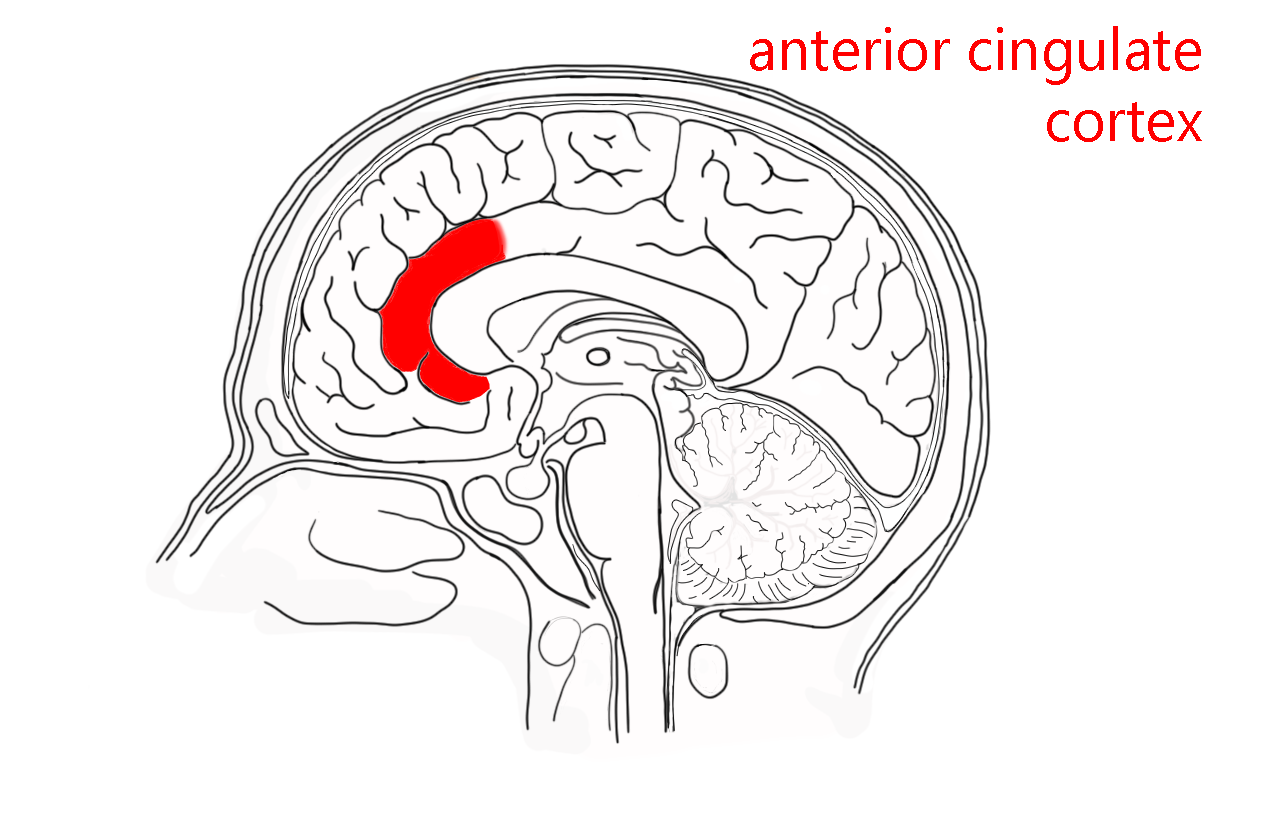

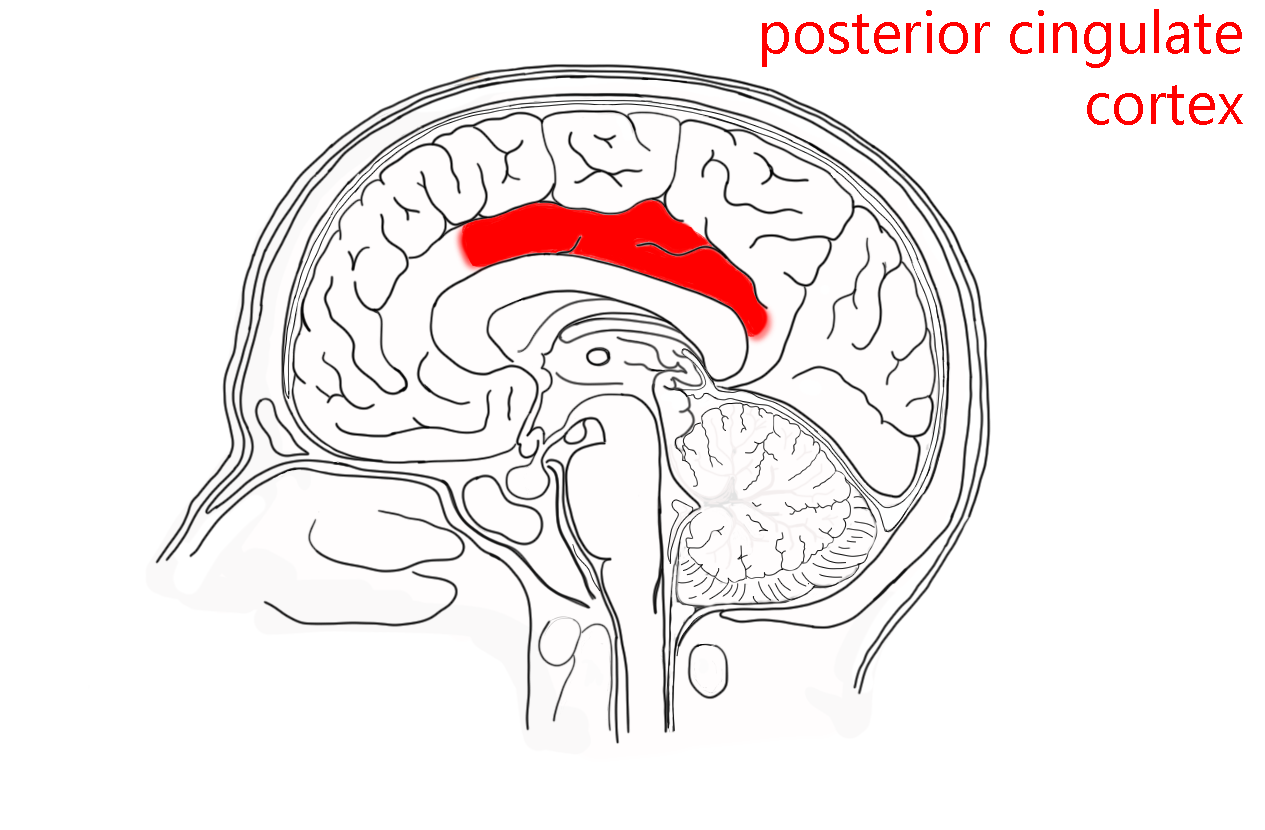

Cingulate Gyrus

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is probably a key component of the affect (mood) regulation system of the brain. For example, multiple studies have shown a role for the ACC in either determining or reflecting political ideology. The ACC connects to both the limbic system (“emotional brain”) and the prefrontal cortex (“cognitive brain”). There are also extensive connections to the insula, which acts in a coordinated fashion with the ACC.

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is probably a key component of the affect (mood) regulation system of the brain. For example, multiple studies have shown a role for the ACC in either determining or reflecting political ideology. The ACC connects to both the limbic system (“emotional brain”) and the prefrontal cortex (“cognitive brain”). There are also extensive connections to the insula, which acts in a coordinated fashion with the ACC.

The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) mediates awareness. For example, it has a role in pain and in episodic memory retrieval. It is a key part of what neuroscientists call the default mode network. This is a group of interconnected brain structures that is most active when you’re not doing anything else (for example, when you are daydreaming or your mind is wandering). As such, it probably plays a large role in human creativity.

The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) mediates awareness. For example, it has a role in pain and in episodic memory retrieval. It is a key part of what neuroscientists call the default mode network. This is a group of interconnected brain structures that is most active when you’re not doing anything else (for example, when you are daydreaming or your mind is wandering). As such, it probably plays a large role in human creativity.

Media Attributions

- Precentral gyrus © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Postcentral gyrus © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Brodmann map © Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H. Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark & DeSaix, Peter is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Cytoarchitectonic areas © Korbinian Brodmann adapted by Stephen Walter Ranson is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Cortical map © Glasser, Matthew Ph.D., and Van Essen, David Ph.D. adapted by Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Primary Somatosensory Cortex lateral view © Database Center for Life Science is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Motor homunculus © Wilder Penfield is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Brodmann area 4 lateral © Anatomography is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Primary somatosensory cortex © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Avalon Marker & Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Parieto-insular vestibular cortex © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Avalon Marker & Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- PIVC lateral surface © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Avalon Marker & Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Primary gustatory cortex © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Avalon Marker and Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Primary motor cortex © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Avalon Marker & Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Premotor area 6 area 8 © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Avalon Marker and Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Broca’s area © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Prefrontal cortex © BioRender adapted by Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Phineas Gage © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gage skull © Harlow, John M. M.D. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Primary visual cortex © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Auditory cortex © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Wernicke’s area © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Anterior cingulate cortex © Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Posterior cingulate cortex © Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license