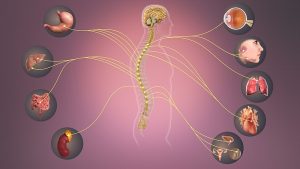

Organization of the Autonomic Motor System

Jim Hutchins

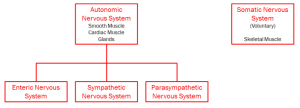

Objective 1: Interpret a flowchart showing the organization of the autonomic nervous system.

General Features of Motor Systems

Motor systems require an effector. This is an output; it causes an effect. The output of the nervous system is either contraction of a muscle or changing the secretion of a gland.

The somatic motor system contracts skeletal muscle. The autonomic motor system (visceral motor system) contracts smooth muscle, contracts cardiac muscle, or changes the secretion of glands.

Motor (Efferent) Pathways

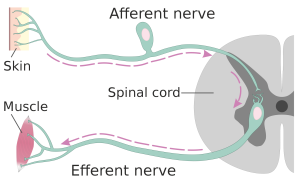

A simple reflex arc, consisting of a sensory neuron (residing in the afferent nerve) in the skin synapsing on a motor neuron (residing in the efferent nerve).Efferent information flows out to effectors. Effectors are grouped into two categories.

Muscles that are controlled consciously are the effectors of the somatic motor system. For this reason, the somatic motor system is also called the voluntary motor system.

Glands and muscles that are controlled automatically, without conscious input, are the effectors of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). (In other words, they do not involve the cerebral cortex, which is where consciousness resides.)

The voluntary muscle system is familiar to us. When we were babies, our parents gave us mobiles and windup thingies in our cribs; we developed eye-hand coordination as we discovered how our skeletal muscles worked. Now, we merely think “touch my nose with my right index finger” and it happens.

We don’t spend much time thinking about the “other” motor system, called the autonomic or visceral nervous system, but it’s critically important for maintaining homeostasis in the human body.

This information outflow originates in parts of the brainstem or spinal cord. Then, it travels to autonomic ganglia and nerves. Then, the information passes through one or several neurons of the ANS to the effectors: smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, or glands.

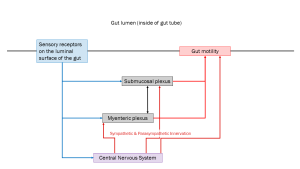

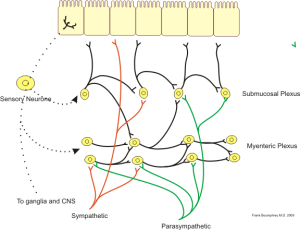

Enteric Nervous System

Many neuroscientists believe there are three divisions to the autonomic nervous system: the enteric nervous system; the sympathetic nervous system; and the parasympathetic nervous system.

The enteric nervous system controls the motility of the gut. It is influenced by, but not controlled by, the central nervous system. Even in the absence of central nervous system input, it carries out the essential functions: controlling secretion from glands of the digestive organs and moving substances within the digestive tract.

Sympathetic Nervous System

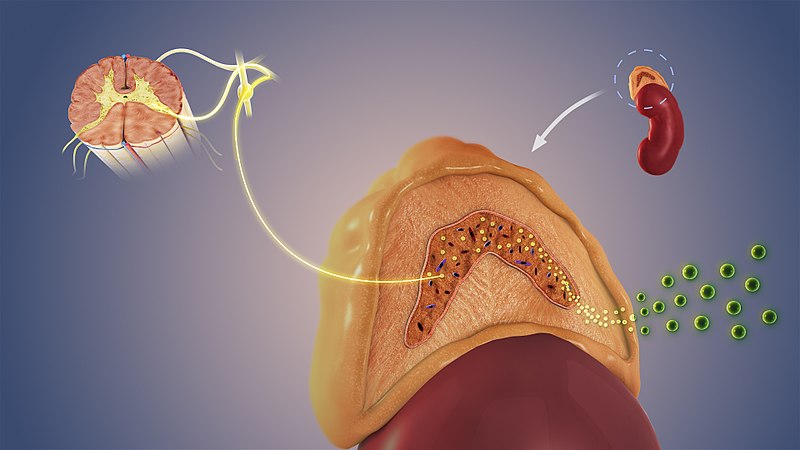

The sympathetic nervous system is commonly referred to as the “fight or flight” system. (Sometimes, slightly more accurately, it’s called the “fight, flight, or freeze” system.) It does more than this, but it’s still a useful shorthand to explain how this system works: by preparing the entire body to respond to dangerous or stressful situations.

One feature of the sympathetic nervous system is its activation of the entire body by releasing chemicals into the bloodstream. Neuronal cell bodies found in the sacral spinal cord send axons out through the greater, lesser, and least splanchnic nerves. These axons release acetylcholine to activate the medulla (core) of the adrenal gland, which is located on top of the kidney. The adrenal gland then releases epinephrine into the bloodstream, preparing the body for fight or flight.

Epinephrine is also called adrenaline. Both names mean “chemical which comes from on top of the kidney”.

Parasympathetic Nervous System

The parasympathetic nervous system is called the “rest and digest” system. It does more than these two things; another mnemonic that helps us remember the function of this system is SLUDD (salivation, lacrimation, urination, digestion, and defecation). In general, the action of the parasympathetic nervous system is in opposition to the action of the sympathetic nervous system.

A key feature of the parasympathetic nervous system is that it is activated organ-by-organ. That is, unlike the sympathetic nervous system, there is no mechanism for “full body” activation of the parasympathetic nervous system.

Media Attributions

- Sympathetic nervous system © Scientific Animations is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Organization of nervous system closeup of motor system © Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Afferent and efferent skin and muscle © Helixitta is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Enteric nervous system wiring diagram with neurons © Boumphreyfr is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Autonomic nervous system overview spinal cord adrenal © Scientific Animations is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license