Localization of Function: Successes and Failures

Jim Hutchins

Objective 4: State the major events that led to an understanding of the localization of function in the brain.

History of Neuroscience Objective 4 Video Lecture

Therefore by the start of the 19th century, there was growing evidence for the Localization of Function hypothesis: contrary to Flourens’ belief, specific areas of the brain were specialized for specific functions. The story of neuroscience in the 1800s is really a steady advancement in our understanding of the localization of specific brain functions, culminating in Korbinian Brodmann’s famous map of the human brain, published in 1909 but still in use today.

We will look at the discoveries which led to the localization of four important brain functions:

- personality

- language

- movement

- vision

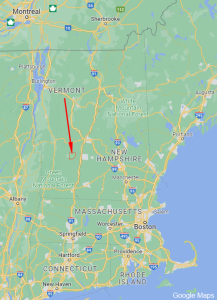

The Brain Location for Personality

On September 13, 1848, a foreman named Phineas Gage was supervising a crew of workmen who were building a railroad line near Cavendish, Vermont. The first American passenger railroad, the Baltimore and Ohio, had been started just 18 years before this, and the United States was in the grip of a railroad-building mania which would reach its peak with the driving of the “golden spike” joining the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroad lines in 1869.

On September 13, 1848, a foreman named Phineas Gage was supervising a crew of workmen who were building a railroad line near Cavendish, Vermont. The first American passenger railroad, the Baltimore and Ohio, had been started just 18 years before this, and the United States was in the grip of a railroad-building mania which would reach its peak with the driving of the “golden spike” joining the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroad lines in 1869.

The area around Cavendish was predominantly flint rock. At the time, dynamite had not been invented, and so if rocks needed to be cleared, the best way was to drill a hole by hand, put a fuse and gunpowder into the resulting hole, cover it with sand to prevent sparks from setting off the charge prematurely, and tamp the whole assembly down with an iron tamping rod 3 cm in diameter and 109 cm long. The tamping iron had one pointy end and one blunt end; the blunt end was used to tamp the charge. The crew foreman was in charge of tamping the charge. Then everyone would go hide behind some rocks, the fuse was lit, and the charge would explode, breaking the rocks into small enough pieces to be moved by the crew.

The area around Cavendish was predominantly flint rock. At the time, dynamite had not been invented, and so if rocks needed to be cleared, the best way was to drill a hole by hand, put a fuse and gunpowder into the resulting hole, cover it with sand to prevent sparks from setting off the charge prematurely, and tamp the whole assembly down with an iron tamping rod 3 cm in diameter and 109 cm long. The tamping iron had one pointy end and one blunt end; the blunt end was used to tamp the charge. The crew foreman was in charge of tamping the charge. Then everyone would go hide behind some rocks, the fuse was lit, and the charge would explode, breaking the rocks into small enough pieces to be moved by the crew.

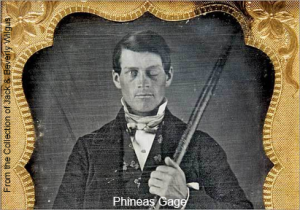

On this day, something went horribly wrong. As Gage bent over the hole to tamp the charge, the iron tamping rod rocketed up through Gage’s left cheek and eye and out the top of his skull, and clattered a few dozen meters away on the rocks they were moving.

Miraculously, Gage survived. He retained all his ability to feel and move and think, except for one major change. His friends said, “Gage is no longer Gage.” His personality had changed irrevocably. A local physician, John Martyn Harlow, treated Gage’s head wound and wrote a paper with the beautifully simple title “Passage of an Iron Rod Through the Head” published in the  Boston Medical and Surgical Journal in December 1848.

Boston Medical and Surgical Journal in December 1848.

The change in Gage’s personality indicated that the frontal cortex, especially that part above the eye called the prefrontal cortex, is essential for the development and maintenance of our personality and the way we interact with others.

The Brain Location for Speech

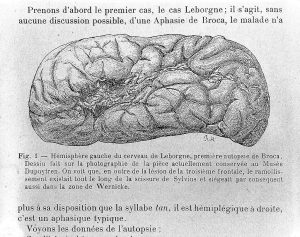

In 1861, French neurologist and neurosurgeon Paul Broca encountered a patient who had once carried the name Louis Victor Leborgne. In 1840, at age 30, his lifelong epileptic seizures had finally rendered him unable to speak except for one syllable. The hospital staff took to calling him “Monsieur Tan” because “tan” was the only word sound he could make; he usually said “tan tan”. Leborgne had been hospitalized for 21 years, since he had no wife or children to care for him, but on April 11, 1861, his paralyzed limbs had become gangrenous and he was transferred to Docteur Broca’s ward.

In those days before antibiotics, not much could be done to combat gangrene, and Leborgne died a week later, on April 17, 1861. Broca obtained his brain for an autopsy and found a striking change in the left frontal cortex: a massive atrophic area. Broca then began collecting brains from similarly situated patients who had died after losing some aspect of the ability to speak. In each and every one, he found a similar atrophic area in the same location. This location, which would 40 years later be called area 44 and area 45 on Brodmann’s map, is also called Broca’s area in honor of Broca’s insight. Broca’s area is found on the left side of the brain in about 7/8 people and on the right side of the brain in about 1/8 people. Having Broca’s area on the right is strongly associated with left-handedness; about 1/4 of left-handed people have Broca’s area on the right. Not just speech, but the production of symbolic language (for example, writing) is located in Broca’s area, and when patients have a stroke or other injury to this area, just like Leborgne, they are unable to speak or their speech is severely impaired. This condition is called aphasia.

In those days before antibiotics, not much could be done to combat gangrene, and Leborgne died a week later, on April 17, 1861. Broca obtained his brain for an autopsy and found a striking change in the left frontal cortex: a massive atrophic area. Broca then began collecting brains from similarly situated patients who had died after losing some aspect of the ability to speak. In each and every one, he found a similar atrophic area in the same location. This location, which would 40 years later be called area 44 and area 45 on Brodmann’s map, is also called Broca’s area in honor of Broca’s insight. Broca’s area is found on the left side of the brain in about 7/8 people and on the right side of the brain in about 1/8 people. Having Broca’s area on the right is strongly associated with left-handedness; about 1/4 of left-handed people have Broca’s area on the right. Not just speech, but the production of symbolic language (for example, writing) is located in Broca’s area, and when patients have a stroke or other injury to this area, just like Leborgne, they are unable to speak or their speech is severely impaired. This condition is called aphasia.

The Brain Location for Movement

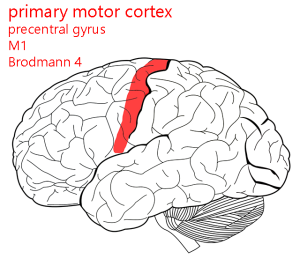

The brain location for movement (primary motor cortex) was discovered in the 19th century.

The brain location for movement (primary motor cortex) was discovered in the 19th century.

The British neurologist John Hughlings Jackson noticed that when patients had seizures, their movement disorders seemed to move from hands up the body to the face. This characteristic pattern, now called a “Jacksonian march”, caused him to hypothesize that different areas of the cortex were responsible for the movement of different parts of the body.

In an 1870 paper, Gustav Theodor Fritsch and Eduard Hitzig electrically stimulated the dog’s brain directly. If they stimulated an area just ahead of the central sulcus, called the precentral gyrus, they observed movement in the muscles on the opposite side (contralateral). Thus, the left side of the brain controls the right side of the body, and vice versa. David Ferrier replicated these findings in the monkey, and now this is a well-established area in all mammalian brains.

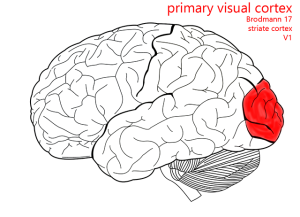

The Brain Location for Vision

The location of vision was discovered, and lost, several times until it was firmly established by a Japanese ophthalmologist, Tatsuji Inouye. The invention of rifling had changed the nature of head wounds in war. Low-muzzle-velocity projectiles, like the minie ball used as ammunition during the US Civil War, had given rise to high-velocity pointed bullets. Minie balls would transfer all of their energy to the inside of the skull, vaporizing a large area of brain tissue. High-velocity bullets, on the other hand, caused through-and-through injuries which made a cylindrical track of damage through the brain. Studying the Japanese victims of the 1905 Russo-Japanese War, who suffered through-and-through injuries of the occipital cortex, Inouye was able to map the location of visual cortex and even establish which parts of the visual field were represented in which parts of the human brain.

The location of vision was discovered, and lost, several times until it was firmly established by a Japanese ophthalmologist, Tatsuji Inouye. The invention of rifling had changed the nature of head wounds in war. Low-muzzle-velocity projectiles, like the minie ball used as ammunition during the US Civil War, had given rise to high-velocity pointed bullets. Minie balls would transfer all of their energy to the inside of the skull, vaporizing a large area of brain tissue. High-velocity bullets, on the other hand, caused through-and-through injuries which made a cylindrical track of damage through the brain. Studying the Japanese victims of the 1905 Russo-Japanese War, who suffered through-and-through injuries of the occipital cortex, Inouye was able to map the location of visual cortex and even establish which parts of the visual field were represented in which parts of the human brain.

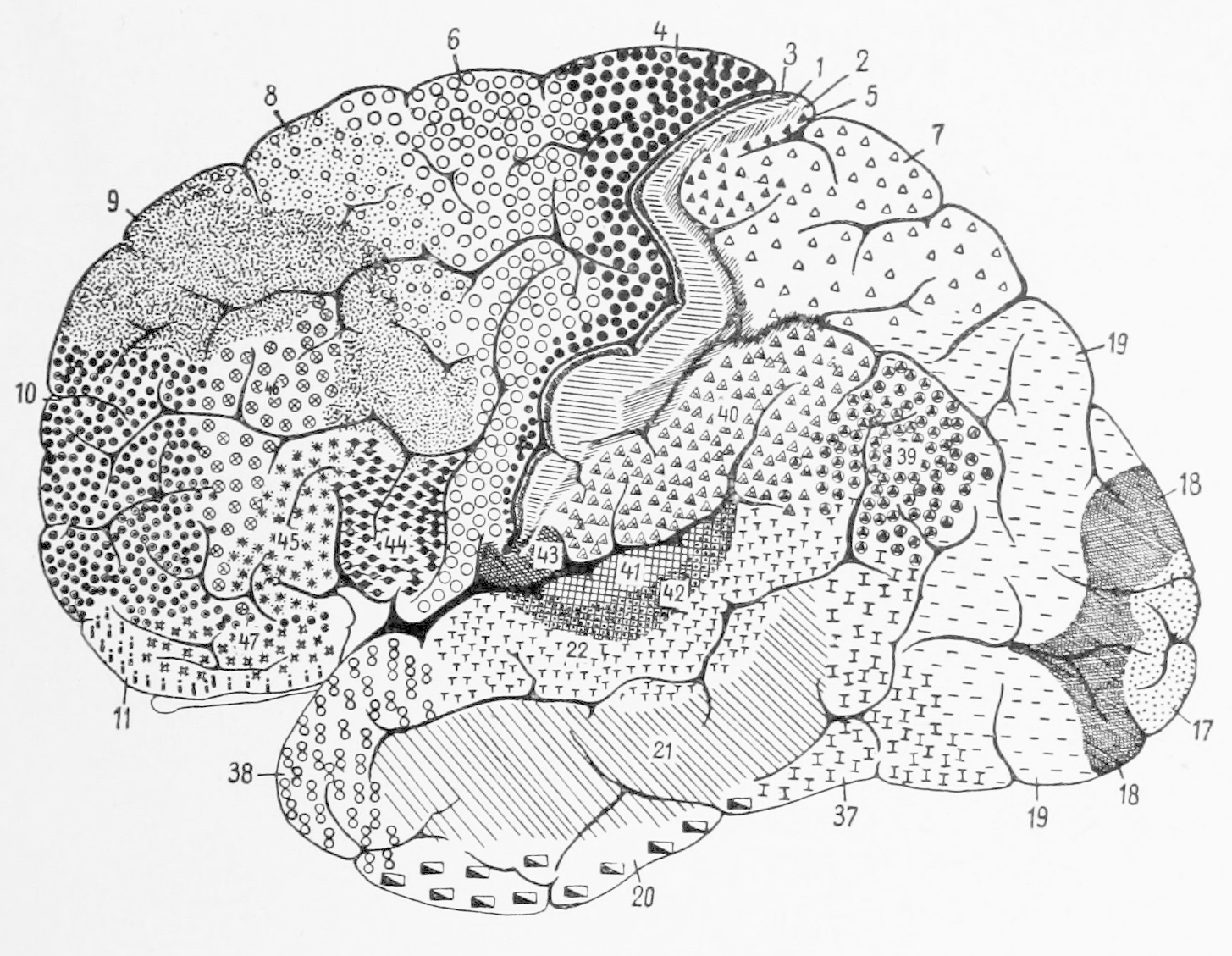

Korbinian Brodmann’s 1909 Map

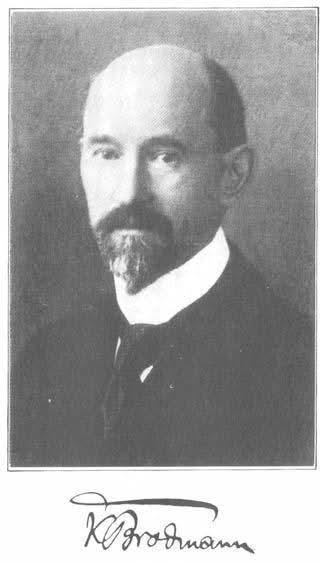

In 1909, the German neuropathologist Korbinian Brodmann published a monograph detailing the cytoarchitectonic areas of human and animal brains. Cytoarchitectonics is the study of how cells are arranged in the brain, making reference to the spacing of cells, their shapes, and their sizes. He did this by slicing the frozen brain with a huge knife, then staining the resulting tissue sections. The first pattern of cytoarchitectonics he encountered, he called “1”; the second pattern, “2”; and so forth. In this way he came up with over 50 patterns. This technique was so powerful, and his work so meticulous, that we use these numbers and this map even today.

In 1909, the German neuropathologist Korbinian Brodmann published a monograph detailing the cytoarchitectonic areas of human and animal brains. Cytoarchitectonics is the study of how cells are arranged in the brain, making reference to the spacing of cells, their shapes, and their sizes. He did this by slicing the frozen brain with a huge knife, then staining the resulting tissue sections. The first pattern of cytoarchitectonics he encountered, he called “1”; the second pattern, “2”; and so forth. In this way he came up with over 50 patterns. This technique was so powerful, and his work so meticulous, that we use these numbers and this map even today.

The areas described in this map correspond to not just the arrangement of neurons, but their function. Thus, the Brodmann map was an important advance in the localization of function.

The areas described in this map correspond to not just the arrangement of neurons, but their function. Thus, the Brodmann map was an important advance in the localization of function.

A Failure: The Brain Location for Memory

Everything was going so well, and there were so many successes in the localization of function, that perhaps it was inevitable that someone would stumble when trying to correlate location with function. In the early part of the 20th century, Karl Lashley and others named the location of the memory trace before they found it. The so-called engram never panned out. It turns out that the entire brain is responsible for the formation of memories; it’s not a location but rather a process.

Localization of Function Studied Directly During Human Brain Surgery

In the first half of the 20th century, Wilder Penfield and Theodore Rasmussen performed dozens of brain surgeries to remove the source of epileptic seizures, tumors, and other abnormal brain structures. While doing so, they applied a small electric shock to the brain and asked the patient (who was still awake, for safety reasons) what they felt. In some cases, like Fritsch and Hirzig, they could see the movement taking place. In this way, they developed maps of motor cortex and somatosensory cortex that they called a homunculus (Latin: “little man”).

In the first half of the 20th century, Wilder Penfield and Theodore Rasmussen performed dozens of brain surgeries to remove the source of epileptic seizures, tumors, and other abnormal brain structures. While doing so, they applied a small electric shock to the brain and asked the patient (who was still awake, for safety reasons) what they felt. In some cases, like Fritsch and Hirzig, they could see the movement taking place. In this way, they developed maps of motor cortex and somatosensory cortex that they called a homunculus (Latin: “little man”).

In their drawings, which are reproduced here as a sculpture, they represented areas with dense sensory input as larger while areas with little sensory input are smaller. Thus the face and tongue and hands of the homunculus are large; almost half of the somatosensory cortex is devoted to these areas.

Media Attributions

- Cavendish plaque © Margo Caufield is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Cavendish map © Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Phineas Gage injury animation © Database Center for Life Science is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Phineas Gage © Jack and Beverly Wilgus is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Paul Broca © Wellcome Collection is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Leborgne brain © Wellcome Collection is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Primary motor cortex © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Avalon Marker & Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Primary visual cortex © Carter, Henry Vandyke adapted by Jim Hutchins and Avalon Marker is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Cytoarchitectonic areas © Korbinian Brodmann adapted by Stephen Walter Ranson is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Korbinian Brodmann © Per Holck is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Brodmann map © Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H. Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark & DeSaix, Peter is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Sensory Homunculus © Mpj29 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license