Internal Anatomy of the Forebrain

Jim Hutchins

Objective 4: Identify the internal structures of the forebrain.

Important Locations Objective 4 Video Lecture

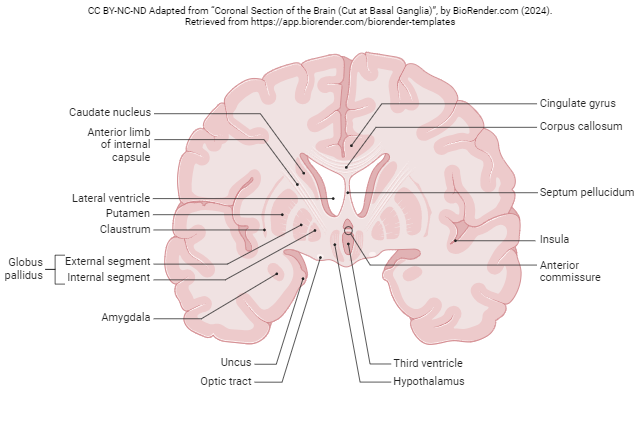

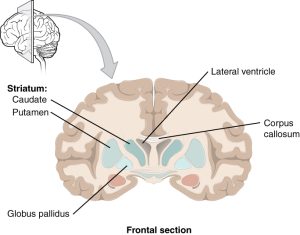

The basal nuclei (blue structures in the diagram) are essential in the control of movement, and regulation of mood and complex behaviors.

An older name for the basal nuclei is basal ganglia. However, we’ve made a big deal of telling you that a “ganglion” is a cluster of nerve cells outside the CNS, and the basal nuclei are definitely part of the CNS, so we’d be hypocritical and confusing to call them “ganglia”, right? That doesn’t stop some neuroscientists from calling it that, but it should.

There are six structures that make up the basal nuclei. Four are found clustered in the forebrain (telencephalon), underneath the cortex and in front of the thalamus.

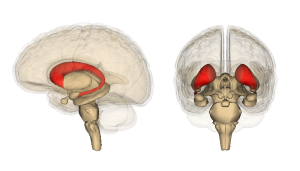

- caudate nucleus (Latin: “s

haped like a tail”; remember “caudal” as an anatomical direction means “toward the tail”);

haped like a tail”; remember “caudal” as an anatomical direction means “toward the tail”); - putamen (Latin: “shell” or “crust”);

- globus pallidus (Latin: “pale globe”);

- ventral pallidum, part of the basal forebrain, underneath the anterior commissure (not shown here)

One is at the junction between the thalamus (diencephalon) and midbrain (mesencephalon):

- subthalamic nucleus

The sixth one is in the midbrain, but anatomically is not far at all from the other five:

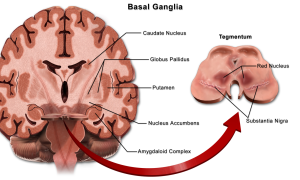

- substantia nigra (Latin: “black substance”), so named because the neurons contain the pigment melanin. It’s easily seen in a cross-section of the midbrain.

The basal nuclei receive dopamine from the substantia nigra of the midbrain; when the nigra dies, the lack of dopamine causes the movement disorders of Parkinson Disease. In about half of Parkinson patients, mental disorders also result. Another degenerative disease of the basal nuclei, Huntington Disease, also results in mental disorders. Obsessive-compulsive patients show abnormalities in the caudate nucleus.

The basal nuclei are also involved in important motor circuitry. There are extensive motor loops connecting the prefrontal cortex as well as the premotor and supplementary motor cortices (area 6) to the caudate and putamen nuclei. The caudate and putamen, in turn, send their output via the globus pallidus (“pale globe”). The globus pallidus sends projections to the ventral anterior and ventral lateral thalamus, mentioned earlier in regard to cerebellar circuitry, and these thalamic nuclei project back to prefrontal cortex and area 6.

An important pathway (the nigrostriatal pathway) starts in the substantia nigra and ends in the caudate and putamen. This pathway provides dopamine to modify movement. These cells are lost in Parkinson disease, with tragic results.

Similarly, a structure called the subthalamic nucleus, which lies — you guessed it — underneath the thalamus at the top of the midbrain, also helps modify movement circuits in the basal nuclei. If the subthalamic nucleus is damaged, the debilitating condition hemiballismus results.

The most important function of the basal nuclei is the initiation and execution of movement. Current thinking is that the basal nuclei play a key role in action selection, choosing the “right” movement from the variety of choices the brain has, especially with regard to the emotional aspects of this choice: will the action result in reward or punishment? For example, asymmetry (left/right imbalance) in the activity of the caudate nuclei is associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and patients with Parkinson disease or Huntington disease have both movement disorders and emotional disturbances.

Media Attributions

- Coronal Section of the Brain (Cut at Basal Ganglia) © BioRender adapted by Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Basal nuclei © Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H. Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark & DeSaix, is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Basal Ganglia © Bruce Blausen is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Caudate and putamen © Avalon Marker and Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Caudate nucleus 3D © Life Science Databases(LSDB) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license