The Major Divisions of the Nervous System

Jim Hutchins

Objective 1: Explain the major divisions of the nervous system.

Nervous System Assembly Objective 1 Video Lecture

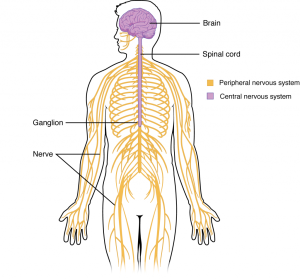

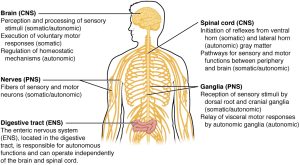

The central nervous system (CNS) is comprised of:

- the brain

- the spinal cord

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is comprised of:

- cranial nerves III-XII

- spinal nerves

- ganglia

- enteric plexuses

- sensory receptors

The key structures of the CNS and PNS have different names. This is one of the ways we can tell if a name refers to CNS or PNS.

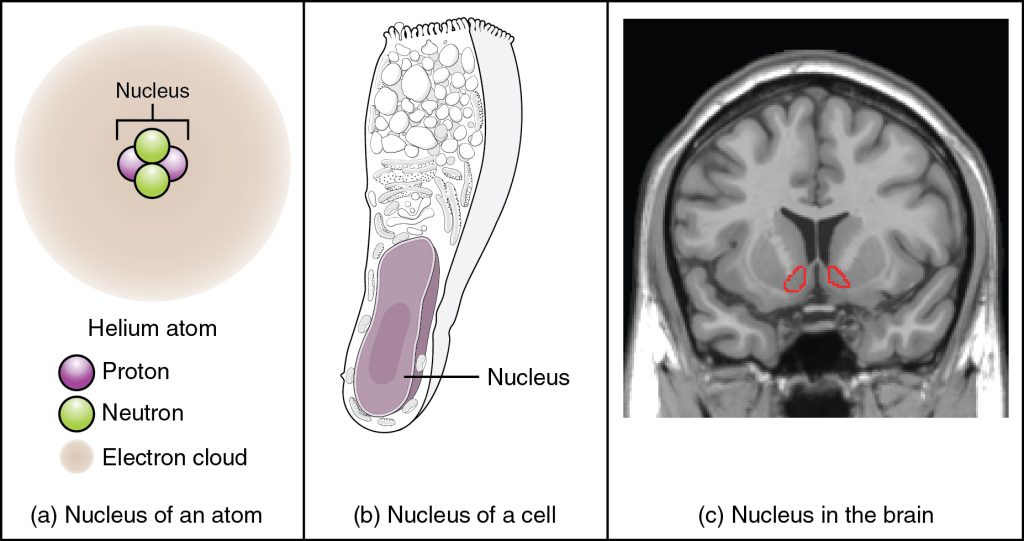

A nucleus (pl. nuclei) is a collection of nerve cell bodies in the CNS. (Note that this is confusing: we have now used the word “nucleus” in three different contexts. “Nucleus” can mean the nucleus of an atom; the nucleus of a cell; or in this Unit, a collection of nerve cell bodies in the CNS. Even more confusing, one group of CNS structures are called the basal ganglia by some authors, which is why many neuroscientists are trying to change the name to the basal nuclei.)

A ganglion (pl. ganglia) is a collection of nerve cell bodies in the PNS.

There are also different names for the pathways carrying information in the CNS, versus the PNS.

A bundle of axons (nerve cell cables) in the CNS that travels together, carrying information from one place to another, is called a tract. Most tracts have logical names: the first half of the name is the origin of the information, and the second half is the termination. The corticospinal tract (Unit 12) travels from the cortex of the brain to the spinal cord.

A bundle of axons in the PNS that travels together, carrying information from one place to another, is called a nerve. Most nerves were named in the Renaissance and so carry descriptive, not functional names. In Unit 9, we learned the Latin name for the hip is ischium. This word got kicked around a little bit and by the time it emerged from the meat grinder of etymology, it became the sciatic nerve which is the nerve associated with the hip. Inflammation of the sciatic nerve is the painful condition called sciatica. Among the cranial nerves, the trigeminal nerve has three pairs of divisions (tri– = “three”; –gemini = “twins”). Pain in the trigeminal nerve is called trigeminal neuralgia (neur– = “nerve”; –algia = “pain”).

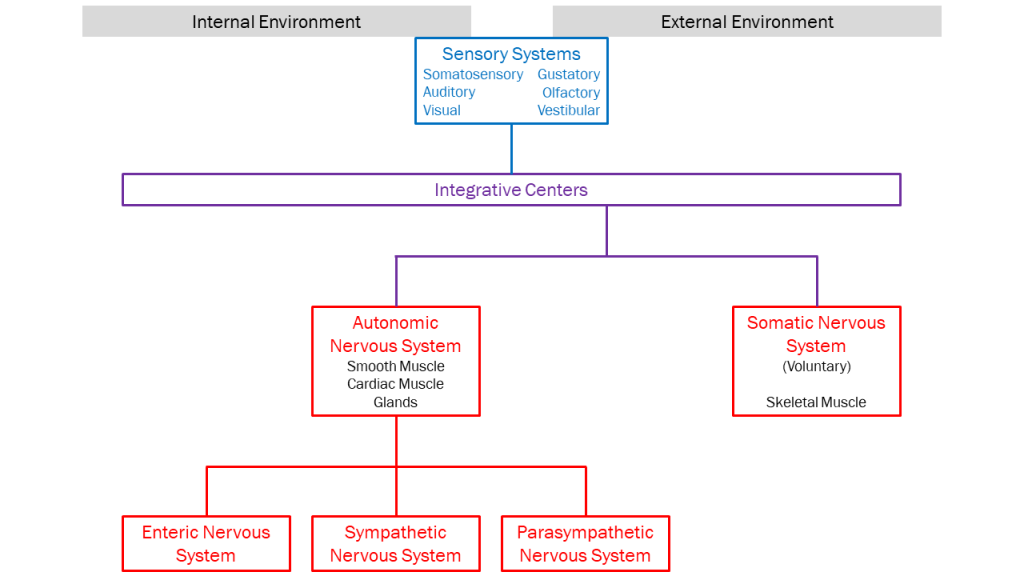

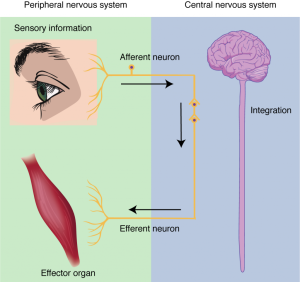

Sensory information originates from the external or internal environment. An example of the external environment is the stream of photons which activates the visual system. An example of the internal environment would be blood osmolarity (salt strength) or blood pressure, as discussed in Unit 1.

Motor information represents the output of the nervous system. No matter how complex the processing between sensory and motor pathways, the only output the nervous system can accomplish is to move a muscle or change the secretion of a gland. Let’s say you’re taking a test and you have to figure out the steps between an alpha motor neuron action potential and muscle contraction (speaking purely theoretically, of course — no one reading this has ever had this experience). How do you express what you believe is the right answer? You could move a muscle (press the correct radio button with your mouse) or change the secretion of a gland (release cortisol from the adrenal gland; release tears from the lacrimal gland).

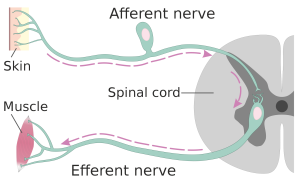

Afferent information flows into the structure we’re referring to. If no particular structure is specified, then we mean the entire CNS.

Efferent information flows out of the structure we’re referring to. Again, the CNS is assumed. (All “eff–“ words mean coming out of: effect, efflux, effector, effluvium.)

For most practical purposes, then, “sensory” is equivalent to “afferent” and “motor” is equivalent to “efferent”. Sensory information is received in the internal or external environment and, through a process called transduction, is converted to a form the nervous system can use. This information flows into the control center from the periphery through the components of the peripheral nervous system (PNS): cranial nerves, spinal nerves, ganglia, enteric plexuses, and sensory receptors.

The information is processed by the control center, namely, the CNS. By definition, the CNS is the brain and spinal cord.

Efferent information flows out to effectors. Effectors are grouped into two categories: those that are controlled consciously, and those that are controlled automatically. The first is the somatic motor system, also called the voluntary motor system. The second of these is the autonomic nervous system (ANS).

The voluntary muscle system is familiar to us. When we were babies, our parents gave us mobiles and windup thingies in our cribs; we developed eye-hand coordination as we discovered how our skeletal muscles worked. Now, we merely think “touch my nose with my right index finger” and it happens.

The somatic motor system controls voluntary movement. Signals that initiate movement begin in the cerebral cortex and cerebellar cortex. These cortices are the gray matter located on the outer portions of the brain (cerebrum) and little brain (cerebellum).

From there, signals pass through nerve cables (axons) to the brainstem centers controlling movement or to the spinal cord. The brainstem centers control the face while the spinal cord has control centers for the rest of the body.

In these control centers, contacts between nerve cells (synapses) relay the information to another set of neurons, called alpha motor neurons (α motor neurons). It is these motor neurons which make contact with skeletal muscle at the neuromuscular junction, as we saw in the muscular system.

In practice, we use the terms somatic motor system, voluntary muscle, and skeletal muscle more or less interchangeably.

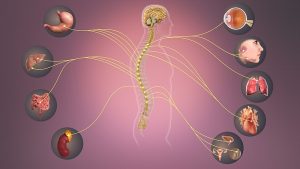

We don’t spend much time thinking about the “other” motor system, called the autonomic or visceral nervous system, but it’s critically important for maintaining homeostasis in the human body.

The autonomic motor system (ANS), comprises those effectors which are not under conscious control. (In other words, they do not involve the cerebral cortex, which is where consciousness resides.)

This information outflow originates in parts of the brainstem or spinal cord. Then, it travels to autonomic ganglia and nerves. Then, the information passes through one or several neurons of the ANS to the effectors: smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, or glands.

This information outflow originates in parts of the brainstem or spinal cord. Then, it travels to autonomic ganglia and nerves. Then, the information passes through one or several neurons of the ANS to the effectors: smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, or glands.

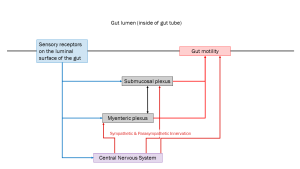

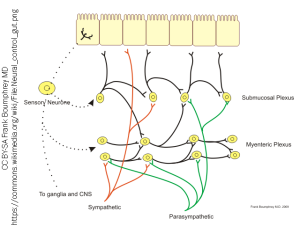

The enteric nervous system (ENS) is found in the gut. Clusters of enteric nervous system neurons are found in the submucosal and myenteric plexi. The ENS is controlled by, and controls, the central nervous system.

Many neuroscientists believe there are three divisions to the autonomic nervous system: the enteric nervous system; the sympathetic nervous system; and the parasympathetic nervous system.

The enteric nervous system controls the motility of the gut. It is influenced by, but not controlled by, the central nervous system. Even in the absence of central nervous system input, it carries out the essential functions: controlling secretion from glands of the digestive organs and moving substances within the digestive tract.

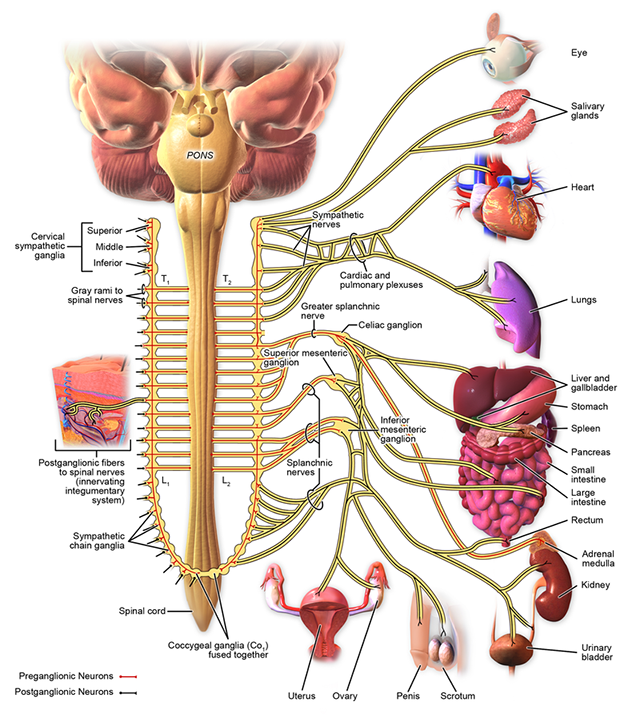

The second division of the autonomic nervous system is the sympathetic division.

Let’s say you are walking along the Mt. Ogden Exercise Trail and a bear shambles out from behind a Gambel oak. Yikes! Your pupils dilate, your mouth gets dry. You stop digesting things so you can shunt blood to your skeletal muscles. Flee!

Let’s say you are walking along the Mt. Ogden Exercise Trail and a bear shambles out from behind a Gambel oak. Yikes! Your pupils dilate, your mouth gets dry. You stop digesting things so you can shunt blood to your skeletal muscles. Flee!

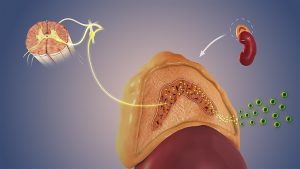

Notice the existence of a positive feedback loop: the sympathetic nervous system stimulates the adrenal glands to make epinephrine (adrenaline), which circulates through the bloodstream to increase fight-or-flight.

The sympathetic nervous system is activated as a unit. All sympathetic nervous system effector organs are stimulated at the same time.

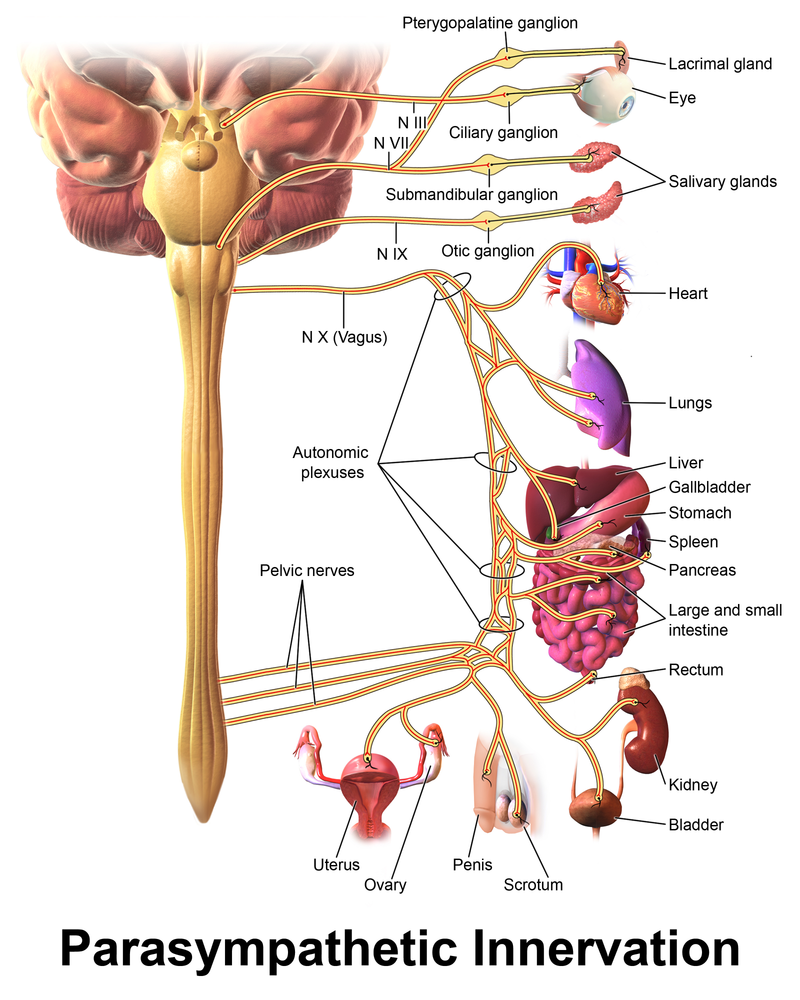

The parasympathetic system, in contrast to the sympathetic system, is not activated all at once. Salivation, bowel motility, digestive secretions, and defecation are all part of the digestive system. Penile (♂) or clitoral (♀) erection are probably inappropriate when fleeing a bear. The heart slows, and the lungs are bathed with moist fluid, at rest. For this reason, the parasympathetic nervous system is often called the “rest and digest” system.

Another mnemonic for the parasympathetic nervous system is SLUDD, the first letters of five key systems it controls: salivation, lacrimation, urination, digestion, and defecation.

The parasympathetic system is wired differently, and uses different neurotransmitters. We never want to activate the parasympathetic nervous system all at once. The only time this happens is when a person is exposed to nerve agent (such as in insecticide intoxication or terrorist attack).

This image will help students review the ways in which we can partition the nervous system into anatomical and functional divisions.

Media Attributions

- Mary Evans Picture © Harlan Farnum is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Overview of nervous system © Lindsay M. Biga, Sierra Dawson, Amy Harwell, Robin Hopkins, Joel Kaufmann, Mike LeMaster, Philip Matern, Katie Morrison-Graham, Devon Quick & Jon Runyeon is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Definitions of nucleus © Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H. Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark & DeSaix, Peter is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Organization of nervous system © Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Afferent and efferent eye and muscle © Lindsay M. Biga, Sierra Dawson, Amy Harwell, Robin Hopkins, Joel Kaufmann, Mike LeMaster, Philip Matern, Katie Morrison-Graham, Devon Quick & Jon Runyeon is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Afferent and efferent skin and muscle © Helixitta is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Sympathetic nervous system © Scientific Animations is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Autonomic nervous system overview spinal cord adrenal © Scientific Animations is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Enteric nervous system diagram © Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Sympathetic Innervation © BruceBlaus is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Shita and her new tiger friends attack © Haakon Lie is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

- Parasympathetic Innervation © BruceBlaus is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Divisions of the nervous system © Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H. Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark & DeSaix, Peter is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license