10 Mindful Teaching, Leadership, and Reflection Practices

Jessie Koltz

“How can I incorporate mindful teaching, leadership, and reflection practices within my courses? And why is it important?”

Feeling confident and excelling personally or professionally may come off as a challenge for educators and students who do not have stress-reducing skills to fall back on. Negative academic or professional stress could then have effects on many aspects of an individual’s life, such as mental health, substance use, sleep, physical health, lackluster achievement in academics and/or personal success, and even school dropout or professional burnout (Proctor, Guttman-Lapin, & Kendrick-Dunn, 2020). How can we engage our students in pedagogical practices focused on how to support mindfulness-based learning, leadership strategies, and reflection practices within higher education settings? How can educators integrate social, emotional, and academic development and learning in courses? How can instructors engage in mindful teaching, leading, and reflecting in our classes? The primary objective of this chapter is to empower educational leaders with tools, strategies, and skills to facilitate systemic change in a positive, healthy, and sustainable way through the integration of mindfulness-based teaching, leadership, and reflection practices.

The Habits of Mind strategies that are highlighted in this chapter include: managing impulsivity, listening with understanding and empathy, applying past knowledge to new situations, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning. These are discussed throughout the chapter and can be integrated into practice in higher education settings.

More specifically, this chapter offers a theoretical understanding and a more comprehensive understanding of:

- The science (the why) that supports the benefits and effectiveness of mindful, social, and emotional learning to support students’ growth and success within coursework.

- Practical techniques and strategies (the how) to use in educational settings to support social, emotional, and academic development cultivation and growth in higher education.

- Guidance on effective leadership strategies (the experience) to support personal and professional social, emotional, and academic development.

This chapter incorporates information from the theories of behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism, and social-learning and social-cognitive theories relating to integrating and teaching Habits of Mind into courses. Cognitive behavioral theory (Beck, 1964), social cognitive theory (Bandura & National Institute of Mental Health, 1986), and the transactional theory of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) are referenced to support practices and reflection.

Now, let us start with understanding the why behind upholding a mindful leadership identity in the classroom setting.

Part I: The Why

The science behind the benefits and effectiveness of mindful social and emotional learning can be found in research (Buchanan, 2017; Sherretz, 2011). Mindful teaching has emerged within teaching practices at universities across the country (Buchanan, 2017). Integrating mindful practices within educational environments can help model positive learning environments for students as well as allow educators to take a breath and slow down during teaching. It has demonstrated effectiveness in reducing stress and increasing prosocial behaviors, too. Integrating breaks and incorporating modeling and intentional reflection during class can support student growth and success (Buchanan, 2017; Sherretz, 2011).

Sherretz (2011) observes that “research provides evidence that mindful teaching practices can have a pronounced positive effect on student learning” (p. 81). Relevant literature relating to stress and academic demands exist for student populations, where much of the research has been conducted with higher education student populations (Pascoe et al., 2019). Intentional and thoughtful mindful practice is a worldly and practical concept to uphold in educational settings. It has proved to be beneficial in managing stress, increasing both attention and self-regulation (Buchanan, 2017). Mindful practices have also been successful improving questioning, listening, and increasing collaboration among teachers and students (Buchanan, 2017). These are all important parts of the Habits of Mind framework that educators should focus on in their teaching practice.

Cognitive Behavioral Theory

Stress reduction skills can be appropriately addressed within a classroom environment by understanding the basics of Cognitive Behavioral Theory (CBT). Developmentally appropriate interventions, techniques, and skills can teach students to support and cope with their perceptions of academic stress while increasing academic engagement levels. Appropriate interventions can educate and help students cope with stressful situations in their academic and social environments.

Modeling and being intentional in the moment to support learning opportunities throughout a course is one way to engage in this practice. Cognitive theories are rooted in the belief that an individual’s thoughts play a major role in the development of emotional and behavioral responses (Gonzalez-Prendes & Resko, 2012). CBT attempts to explain human behavior by understanding the individual’s thought process, an individual’s beliefs to a situation, how the situation is interpreted, and how the individual then carries out the necessary skills (Beck, 2000).

Aaron Beck expanded on cognitive theory through the creation of his cognitive model, describing how perceptions of situations and automatic thoughts influence behaviors. Beck’s (1964 2000) cognitive model describes the cognitive process of reacting to situations by first identifying the stressful situation, evaluating automatic thoughts, and reacting to those automatic thoughts. Cognitive behavioral approaches make individuals more aware of their own thoughts and help them be more intentionally reflective on thoughts that then influence emotions, behaviors, or physiological reactions.

Social Cognitive Theory

Social cognitive theory (SCT) emerged in 1986, stemming from the social learning theory that Albert Bandura developed in the 1960s. Social cognitive theory discusses the influence of social reinforcement on human behavior regarding the interaction of the environment. SCT addresses how individuals learn from personal experiences as well as through the observation of others (Glanz & Bishop, 2010). Every day, students are affected by their environments and experiences; each situation affects their well-being, learning, and social interactions (Weissberg & Cascarino, 2013). SCT emphasizes interactions between individuals or the environment and has been applied in several interventions (Burgess-Champoux et al., 2008; Gaines & Turner, 2009; Koo et al., 2019). Attending to social and emotional strategies in the here and now supports individual growth and development (Weissberg & Cascarino, 2013).

Elements of modifying behavior are inclusive of self-control, self-efficacy, and reinforcement within social cognitive theory. Goal-setting and self-monitoring have been stated to be effective within interventions using SCT (Bandura, 1986; McLeod, 2015). SCT’s key component of reciprocal determinism proposes that an individual can be both an agent for change and a responder to change, referring to the influence of their role models, teachers, peers, guardians, the environment, and reinforcements promoting healthy behaviors (Bandura, 1986; McLeaod, 2015). SCT offers a foundation to identify behaviors that can be modified, while also explaining how the behavior is related to the relationships between the individual’s personal factors and environmental influences (Koo et al., 2019).

The Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping

Created by Richard Lazarus (1966), the transactional theory of stress and coping identifies stress as a mental process where an individual reflects on their environment and recognizes they do not have the resources available to cope with the identified stressor. Like in social cognitive theory, stress is a result of interactions between the individual and their environment. This theory is a framework to evaluate the practice of coping with stress. The individual identifies that their emotions are caused by the stressor and the individual assesses their coping resources and strategies to control their emotions, resulting in identifying their stress. Coping helps to regulate distress and serves as the management of the problem caused from the stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Supporting students with increased resources to adopt learned coping skills and strategies helps them identify their stressor(s) and cope successfully.

Two cognitive appraisals are identified within the transactional model of stress and coping. During primary appraisal, the individual questions what is at stake during a stressful, threatening situation; within the secondary appraisal, the individual questions what they can do about the stress to respond to the threat (Margaret et al., 2018). For example, if the individual recognizes that they have the resources to cope with their perceived stressor, then they will pull from their available coping resources to support a stable response to result in a better mood and relaxed demeanor for an immediate short-term outcome to the situation. The transactional theory of stress and coping posits that individuals are continuously assessing stressors within their environment, adapting to their surroundings and their need to cope with identified stress using available resources (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

CBT, SCT, and the transactional theory of stress and coping are reliable theories to be aware of within educational environments. Theories such as these address maladaptive thinking and behaviors while attending to learned coping strategies. These theoretical approaches also help students develop positive social skills, support a positive learning environment, and assist in the growth of academic and emotional functioning.

Mindful Social, Emotional, and Academic Development

Mindful individuals can identify several viewpoints in any situation by being present in the moment (Sherretz, 2011). Mindfulness-based leadership in the classroom is when an educator can be intentional, reflective, and purposeful in not only their content, but in their self and their emotional regulation and management. This ability helps the educator communicate and model perspective taking with their students. “Mindfulness is a process in which the individual steps back from the perceived problem and perceived solutions in order to view the situation in a new and novel way…where meaning is given to the outcomes through the process” (Sherretz, 2011, p. 80). Being mindful in social, emotional, and academic development can enhance and support the learning environment for students. Managing thoughts and reflecting on emotions without judgment can help educators be aware of their regular day-to-day stressors, “which in turn can lead to a vast array of additional benefits including students experiencing less stress, recognizing teachable moments and taking advantage of them in the moment to enhance learning” (Buchanan, 2017, p. 74).

Establishing a community of trust and getting to know students is essential to supporting a culture of respect and connection. As Kim (2020) notes, the quality of student-teacher connections has a strong and consistent relationship to the quality of future health compared with student-student relationships. The results of this research indicate that educator training should include social emotional learning and development to support interpersonal skills to help teachers assess and adjust beliefs as well as practices in the classroom (Kim, 2020). Being aware of and understanding how to support a social emotional connection with students while incorporating effective strategies can lead to enhancement in the quality of the student-teacher relationship.

Mindfulness activities improve our understanding of our character, traits, triggers, and beliefs, which then leads to self-awareness and self-control. Knowing when to use the “pause button” and slow down in the moment while teaching can support trust and enhance the relationship an educator has with their students. Mindfulness allows adults to recognize physical changes within themselves, changes that signal potential for self-care, communication, and decision making. Emotional regulation skills are essential for personal and professional awareness. Providing time for adult learners to assess and reflect on their beliefs, behaviors, and choices outside of moments of escalation can enhance emotional understanding and regulation skills. This approach can further support an overall greater and more authentic way of living.

Now, let us apply these principles and learn more about how to practice mindfulness-based leadership to support student development and learning.

Part 2: The How

In our courses, we want to support student learning to the best of our ability. We can do this by incorporating practical techniques and strategies, such as Habits of Mind that support social, emotional, and academic development cultivation and growth in higher education. The Habits of Mind that are integrated into the following practices include: managing impulsivity, listening with understanding and empathy, applying past knowledge to new situations, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning.

Where can educators integrate mindful teaching, leadership, and reflective practices? The answer is: Everywhere! Through active practice and modeling, educators can support self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and even enhance responsible decision making (CASEL, 2020). They can incorporate mindful practices at the beginning, middle, and end of classes; in presentations; interviews; and meetings and during mentoring and supervision. Helmer (2014) makes this exact point:

If critical teacher educators wish to instill in prospective teachers this understanding about themselves as transformative educators, they must enact practices in their own classrooms that disrupt and not replicate dominant notions of teaching and learning reflected in what Freire (2000/1970) called the banking model of education. One of the key elements of such critical teaching practices involves the deconstruction of classroom interactions and dynamics so that spaces open up where teacher and students can collectively and creatively co-construct knowledge (p. 33).

The following strategies can help educators and students co-construct knowledge, as Helmer (2014) suggests:

- Model, model, model

- Positive self-talk

- Repetition

- Mindful transitions

- Journals for planning or reflecting

- Visual techniques

- Mindfulness exercises

- Goal setting

- Checking in

- Setting group values/norms

- Settings intentions/objectives and connecting back to the objectives

- Getting to know your students

- A, E, I, O, U

Model, Model, Model

Educators should model the strategies they would like their learning environment to encompass. This strategy can be incorporated at the start of a class or supervision meeting, during the beginning of the lecture, before or after an exam, or between topics. We need to mindfully model what we intend, how to react in the moment when we are teaching, and when we influence our adult learners. No matter the outcome of the modeling in practice, we must be sure to give ourselves grace and gratitude at the end of every teaching experience, no matter how late the workday lasts. Educating students on reflective practice skills, modeling with intentionality, and incorporating practice in the moment fosters cognitive learning and reinforcement. The Habits of Mind of managing impulsivity, listening with understanding and empathy, applying past knowledge to new situations, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning can all be applied in this strategy.

Positive Self-Talk

Modeling active positive self-talk in your courses is a mindfulness strategy to incorporate in one’s teaching. Educating students on skills and reiterating that thoughts influence behaviors fosters the cognitive area of this practice. Reinforcing positive thinking and thought management can encourage self-control and promote self-efficacy. Reflecting on the environment around you can enhance stress-reducing skills and support positive coping techniques through active practice. The Habits of Mind areas of managing impulsivity, listening with understanding and empathy, applying past knowledge to new situations, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning all can be applied in this strategy.

Repetition

Weaving mindful social emotional learning practices into a course routine and being intentional by having a mindful moment or two with students is important to enhance repetition and rehearse mindfulness strategies. The Habits of Mind areas of applying past knowledge to new situations, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning can be applied in this strategy. Repetitive education of skills, modeling, and reiterating positive strategies and behaviors encourages the cognitive capacity of this practice. Reinforcing skills is also included here to promote self-efficacy. Recognizing resources that are available to students can help the educator as well as students with in-the-moment coping skills.

Social and emotional learning (SEL) practice is not intended to always be a lesson, though. SEL should be visited throughout a course; it is intentional to practice it in the moment. Some good periods to incorporate reflective practices are at the start of class, after an activity, when a break is needed, or at the end of the class.

Mindful Transitions

Start with one transition to regularly practice, such as a brain or movement break with students during the time that usually follows a lecture or group discussion. Ask students to concentrate on any internal or external sensation, sound, thought, feeling, or sensory experience that arises. Ask them to breathe and to bring awareness to the present. And, as this practice becomes easier, add other transitional moments throughout the class. Continue to further your practice and make the most of the “in-between” moments. The Habits of Mind of managing impulsivity, listening with understanding and empathy, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning all can be applied in this strategy.

Skill building, active practice, and positive enforcement of coping skills from cognitive behavioral theory are included in this practice, along with reinforcing skills from social cognitive theory to promote self-efficacy. Having students recognize what resources are available that are regularly and actively incorporated in class relates to the transactional theory of stress and coping with consistently practicing coping and mindfulness skills.

Journals for Planning or Reflecting

Incorporating mindful thinking through journaling is another strategy to introduce mindful teaching and reflection in a class. Having students write, draw, plan with their schedule/calendar, set goals, create a to-do list, identify temperature checks or craft a “How do I feel today” journal entry, reference a quote, or create a list of research or mentoring ideas can support this strategy. The Habits of Mind of listening with understanding and empathy, applying past knowledge to new situations, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning can all be applied in this strategy. Skill building, active practice, and positive enforcement from CBT are included in this practice along with reinforcement and reflection from SCT to promote self-efficacy.

Visual Techniques

Visualizing by using pictures and incorporating imagery (through imaginative practices) can also enhance mindful teaching and learning practices. The Habits of Mind of gathering data through all senses and remaining open to continuous learning can be applied in this strategy. Educators can foster self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making through this practice. See Appendix B for some visualization techniques to try in one’s learning environment.

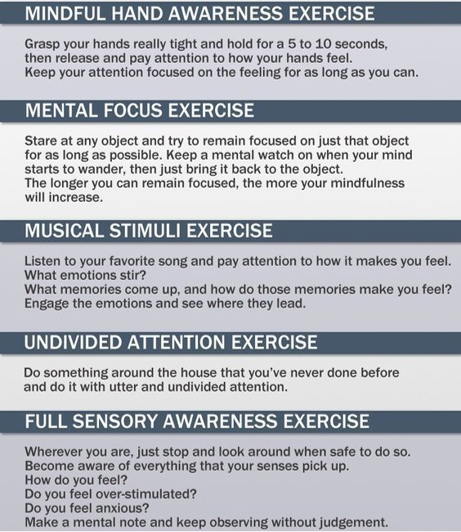

Mindfulness Exercises

Breathing and visual and grounding techniques can be helpful for calming and regrouping by focusing on the present. Completing an activity that incorporates our senses can help bring us back to the present and reduce anxiety or other negative feelings. The Habits of Mind of managing impulsivity, listening with understanding and empathy, applying past knowledge to new situations, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning can all be applied in this strategy.

This practice enhances skill building through active practice of mindfulness skills while promoting self-efficacy, recognizing resources that are actively incorporated in class through regular practice of skills. Refer to Appendix B for additional mindfulness exercises to support the learning environment. Also reference this example for your practice:

- FEEL: Name five sensations that you can feel in your body. For example, my shirt against my skin, the chair pressing into my heel, or an itch behind my shoulder.

- HEAR: Name four things you can hear. For example, a dog barking nearby, the sound of cars passing, the clock ticking, or the air conditioning running.

- SEE: Name three things that you can see. For example, a red book, a lavender bush, or an office desktop.

- SMELL: Name two things you can smell. For example, fresh air, the food someone brought into class, or asphalt.

- TASTE: Name one thing you can taste. For example, leftover cookie crumbs, toothpaste, or morning breath.

Goal Setting

Putting goals into action can support mindfulness in the present and awareness of future behaviors. The Habits of Mind of applying past knowledge to new situations, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning can be applied in this strategy. Active practice and positive enforcement of goal-setting skills are included in this practice to support intentionality and cognitive reinforcement, to promote self-efficacy, and to recognize resources that are actively incorporated in class. An example could be to ask students the following: What are one or two goals you can think of right now for yourself—personally, professionally, and/or academically? What changes can you implement right now to move towards these goals?

Check-In

Giving students a voice is important to enhance connection, trust, and incorporate another mindful leadership technique in practice. The Habits of Mind of listening with understanding and empathy, applying past knowledge to new situations, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning can be applied in this strategy. Continual check-ins support positively reinforcing awareness of the present and goal-setting skills from CBT; reinforcement from SCT to promote self-efficacy; and recognition of self-awareness and goal-setting resources relating to the transactional theory of stress and coping with regularly identifying awareness and areas of growth. Ask students: How are you (really) at this moment in the class? Labeling and recognizing emotions and being fine with whatever emotion is present can support awareness and a sense of relief that “this emotion is OK.” Also ask: How do you want to be? Intentionally identifying goals to support recentering and adjusting behaviors lets students know you care and are interested in their wellness.

Setting Group Values/Norms

Being intentional with expectations and bringing in student voice and perspective to create a shared group value or norm list can be an effective strategy to encourage involvement and engagement in a class. The Habits of Mind of managing impulsivity, listening with understanding and empathy, applying past knowledge to new situations, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning all can be applied in this strategy.

Active acknowledgement of norms supports a positive environment. This approach enhances the learning environment through cognitive awareness; it reinforces positive values from a social cognitive lens by recognizing resources that are actively united in class rituals and routines. These processes relate to the transactional theory of stress and coping with regular practice.

Here are two examples of setting group values and norms:

- We will respect everyone’s time and learning by:

- starting and ending on time.

- blocking off this time without interruptions.

- putting away technology (phones/computers) unless you are using them to participate in class learning.

- being genuine with each other about ideas, challenges, and feelings.

- staying focused on goals and the intent behind a class session.

- being willing to explore a positive edge and untapped potential.

- The norms for today are:

- This is a safe place.

- We want you to stay open to all viewpoints.

- Be genuine with each other about ideas, challenges, and feelings.

- Be engaged by contributing to conversations, asking questions, and turning off technology.

- Assume positive intent.

Setting Intentions/Objectives and Connecting Back to the Objectives

Having students identify academic learning intentions, learning standards, or personal learning objectives can support intentionality in learning. The Habits of Mind of applying past knowledge to new situations and remaining open to continuous learning can be applied in this strategy.

Active acknowledgement of intentionality and connecting back to personal intentions or course-related objectives supports a positive learning environment through cognitive practice, reinforcing positive values from a social cognitive lens, and recognizing resources that are regularly incorporated into class routines. Connecting back to objectives can enhance goal setting through regular practice. Some examples include asking students to reflect on the following:

- Coming into class today, I feel…

- For this class, my intention is…

- What I would like to focus on today is…

We do not always have the time to reference mindful intentions during every class interaction; but intentions should be made a priority at some point in the course. Asking students to reflect on the following can improve mindful learning:

- What is the purpose (of the assignment or reading)?

- Why is this important to your learning?

- What are the meaningful outcomes to put into practice?

Getting to Know Your Students

Ensuring you get to know your students during and between class meetings shows interest not only in their academic ability but in them as individuals. The Habits of Mind of listening with understanding and empathy, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning can all be applied in this strategy. Highlighting a student in each module throughout a course, on a course website, or in a local edition of a newsletter or program journal could help you to get to know your students.

A, E, I, O, U

Using the following mnemonic can support student understanding of their knowledge of your teaching while upholding intentional mindful practice. The Habits of Mind of applying past knowledge to new situations, gathering data through all senses, and remaining open to continuous learning can be applied in this strategy, as evidenced in the following mnemonic:

A–Adjective: Do you have an adjective that comes to mind that describes your learning?

E–Emotion: What emotions or feelings do you have in reflection?

I–Interesting: What made you curious?

O–Oh!: What a-ha moments did you have?

U–Um?: What questions do you still have?

It is important to experience these practices yourself and understand how you will implement each technique into practice.

Part 3: The Experience

It is important to connect with your students. Connecting with them through personal experiences will inhibit trust, a willingness to engage, and openness to share and be vulnerable in the environment you are teaching. Incorporating effective leadership strategies into your teaching can help support students with their personal, social, emotional, and academic development.

A personal reflective practice that we all integrate into our careers as educators includes a teaching or mentoring philosophy. When we craft these documents, we must ask: What is your why? Reflecting on this question can help us create a culture of empowerment. This can be a reflection on relationship building, mindfulness skill development and practice, and overall personal and professional well-being. Mindful leadership incorporates inclusive initiatives, addressing the needs of yourself, along with the needs of faculty, staff, and students. Being mindful in your leadership includes supporting equity, student and faculty engagement, and professional and/or academic achievement through mindful and restorative practices.

Not everyone will feel comfortable, at least at first, when they try to implement these practices. However, when beginning to practice mindfulness and meditation, it is useful to browse a variety of resources. Jeffrey Brantley (2007), founder of the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program at Duke University’s Center for Integrative Medicine, notes:

There are thousands of books, tapes, and videos about meditation.…Different meditation teachers often give somewhat different instructions or emphasize a different aspect of the instructions.…Do not take anyone too literally. Instead, try to understand the essence of what is being taught. (p. 94–95)

Be intentional—and mindful—with what you hope to accomplish in your class and be focused on the Habits of Mind that your teaching practices foster in students. That way, you can accomplish what you hope to in your courses.

References

Bandura, A., & National Institute of Mental Health. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Beck, A. T. (1964). Thinking and depression 2: Theory and therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 10, 561–571.

Buchanan, T. K. (2017). Mindfulness and meditation in education. YC Young Children, 72(3), 69–74. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90013688

Burgess-Champoux, T. L., Chan, H. W., Rosen, R., Marquart, L., & Reicks, M. (2008). Healthy whole-grain choices for children and parents: A multi-component school-based pilot intervention. Public Health Nutrition, 11(20), 849–859.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2020). CASEL’s SEL Framework: What are the core competence areas and where are they promoted? https://casel.org/what-is-sel/

Gaines, A., & Turner, L. W. (2009). Improving fruit and vegetable intake among children: A review of interventions utilizing the social cognitive theory. CJHP, 7, 52–66.

Glanz, K., & Bishop, D. (2010). The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annual Review of Public Health, 31, 399–418.

Gonzalez-Prendes, A. A., & Resko, S. M. (2012). Cognitive-behavioral theory. In J. R. Brandell & S. Ringel (Eds.), Trauma: Contemporary directions in theory, practice, and research. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Helmer, K. (2014). Disruptive practices: Enacting critical pedagogy through meditation, community building, and explorative spaces in a graduate course for pre-service teachers. The Journal of Classroom Interaction, 49(2), 33–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44735702

Kim, J. (2020). Positive student-teacher relationships benefit students’ long-term health, Study finds. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2020/10/student-teacher-relationships

Koo, H. C., Poh, B. K., & Rauzita, A. T. (2019). Great-Child Trial™ based on social cognitive theory improved knowledge, attitudes and practices toward whole grains among Malaysian overweight and obese children. BMC Public Health, 19(1574), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7888-5

Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. McGraw-Hill.

Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

Margaret, K., Simon, N., & Sabina, M. (2018). Sources of occupational stress and coping strategies among teachers in Borstal institutions in Kenya. Edelweiss: Psychiatry Open Access, 2(1), 18–21.

McLeod, S. A. (2015). Cognitive behavioral therapy. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/cognitive-therapy.html

Sherretz, C. E. (2011). Mindfulness in education: Case studies of mindful teachers and their teaching practices. Journal of Thought, 46(3–4), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/jthought.46.3-4.79

Weissberg, R., & Cascarino, J. (2013). Academic learning + social-emotional learning = national priority. Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. https://www.sd44.ca/school/handsworth/About/handsworthvisionserviceinaction/socialandemotionallearning/Documents/Academic%20Learning%20+%20Social-Emotional%20Learning%20=%20National%20Priority.pdf

Appendix A

Mindful Practices

Appendix B

Mindfulness and Meditation Resources, Buchanan (2017)

Guided Meditations

- Awakening to Being Present, by Gael Chiarella (from AM Yoga Meditations) https://youtu.be/ue-JBc7hMXY

- Breathscape and Bodyscape Guided Meditation, by Jon Kabat Zinn http://dai.ly/x2yv79f

- Loving Kindness Meditation, by University of New Hampshire Health Services https://youtu.be/sz7cpV7ERsM

Open-Eyed Meditations

- How to Meditate with Open Eyes, by Brahma Kumaris Glasgow https://youtu.be/kiceMRy6ZG0

- The Journey to Your Self: Remembering the Real You, by Ken Obermeyer https://youtu.be/BPj8G2_b9Uk

- The Sound of the Bell, from Plum Village Meditations, by Thich Nhat Hanh, video by stevieboytheMt1

- https://youtu.be/p-uBnDH-YNs

Documentaries

- On Meditation: Documenting the Inner Journey, by Snapdragon Films http://onmeditation.com/

- Room to Breathe, by Sacred Planet Films www.mindfulschools.org/resources/room-to-breathe

- Walk With Me, by Speakit Films

- http://walkwithmefilm.com