6 #DigitalPowerups: Creating Safe and Brave Spaces in Online Discussions to Support Student Choice and Voice

Leonard A. Henderson; Travis Thurston; Mehmet Soyer; Gonca Soyer; and Josie Tollefson

When structured effectively, online discussions can create safe and brave spaces (Murphy et al., 2020) for students to engage in meaningful dialogue surrounding traditionally difficult topics, like gender and sexuality. Yet it can be challenging to motivate students to participate in online discussions (Moore, 2021). In this chapter, we show how the #digitalpowerups strategy provides an innovative and effective way for instructors to engage students in higher-order online discussion by developing Habits of Mind skills, such as applying past knowledge to new situations, thinking about your thinking (metacognition), listening and understanding with empathy, thinking interdependently, responding with wonder and awe, and striving for accuracy (Al-Zakri & Al-Jubair, 2020; Costa & Kallick, 2009).

#Digitalpowerups are keywords displayed as hashtags that are associated with corresponding prompts in online discussion forums allowing for both student choice and student voice. The #digitalpowerups strategy is theoretically grounded in the dynamic interplay between social and cognitive presence in the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework. At its core, CoI “is social constructivist in nature and is concerned with deep and meaningful learning” (Joksimović et al., 2015, p. 640). CoI must be centered in a learning environment that encourages discourse and community building as a means of engaging students in an educational experience (Garrison et al., 2010). Specifically, the #digitalpowerups strategy was designed to empower students with autonomy and choice, which opens opportunities for students to engage in course activities (Lee et al., 2015; Reeve & Jang, 2006). Although online discussions can “allow students to participate actively and interact with students and faculty” (Baglione & Nastanski, 2007, p. 139), without proper course design and teacher presence, online discussions tend to focus on a “lower level of thinking and discourse” (Christopher et al., 2004, p. 170).

Using #digitalpowerups not only helps students structure their responses. The use of hashtags in online discussions also challenges students to enrich their discussion as they build the Habits of Mind necessary for success in online discussions. In this chapter, we scrutinize how #digitalpowerups support student learning in a dynamic virtual community for difficult topics in SOC 3010: Social Inequality, an undergraduate course at Utah State University (USU). We share the theoretical underpinnings of #digitalpowerups and results from scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) studies. We also offer detailed insights on ways instructors can implement this strategy in their courses.

Digital Powerups in Online Discussions

Digital powerups have recently come to the forefront of innovative strategies in higher education. Although they originated in K-12 settings (Gustafson, 2014, 2016) with younger students, #digitalpowerups have also been applied in postsecondary settings. Thurston (2020) published the first study on #digitalpowerups with graduate students. Subsequent studies on #digitalpowerups combined the strategy with think-alouds for graduate students (Mardi, 2020, 2022). Figure 6.1 lists the related Habits of Mind skills that resulted from these studies. In this chapter, we specifically explore using #digitalpowerups in the context of undergraduate sociology coursework. Since #digitalpowerups are an emerging engagement strategy, there are limited studies on the specific strategy itself; however, the strategy is deeply connected to the literature on social constructivist approaches to learning, the literature on online discussions, and the robust literature on Habits of Mind.

Figure 6.1

Habits of Mind Student Outcomes From #digitalpowerups

|

Thurston, 2020 |

Mardi, 2020 |

Mardi, 2022 |

|

Thinking about your thinking (metacognition) Creating, imagining, and innovating Remaining open to continuous learning Thinking interdependently

|

Thinking about your thinking (metacognition) Applying past knowledge to new situations Questioning and posing problems Thinking interdependently |

Thinking about your thinking (metacognition) Creating, imagining, and innovating Thinking and communicating with clarity and precision Thinking interdependently |

Many instructors struggle to authentically engage students in online learning (Allen et al., 2016; Herman & Nilson, 2018). This is not surprising given the inadequacies that exist in the design and facilitation of online discussion forums, such as not engaging students in higher order thinking (Andresen, 2009; Gao et al., 2013; Hay et al., 2004) and not allowing co-construction of knowledge and reflection (Cho & Cho, 2016; Lambiase, 2010). Importantly, these inadequacies can be mitigated in part by using the design and instruction of a strategy like #digitalpowerups.

Gustafson (2014) originally proposed #digitalpowerups to address the insufficiency of authentic engagement in online discussion boards. Gustafson proposes that the use of these powerups enhances engagement from lower level responses to higher order thinking in Bloom’s revised taxonomy (Krathwohl, 2002). Instructors can use Bloom’s taxonomy as a scaffold to amplify student engagement and higher order learning (Cheung et al., 2008; Christopher et al., 2004; Darabi et al., 2011; Ertmer et al., 2011; Gilbert & Dabbagh, 2005; Valcke et al., 2009; Whiteley, 2014). Employing hashtags is one way to use Bloom’s taxonomy as a scaffold in online discussions. A hashtag, which is a number sign (#) followed by a keyword (Pacansky-Brock, 2012), can be used as visual or textual representations of prompts in the #digitalpowerups strategy. By explicitly labeling different levels of Bloom’s taxonomy with specific prompts or hashtags, students provide a clue as to the level (e.g., #remember, #understand, #apply) at which they are engaging in the discussion.

Making students aware of Bloom’s taxonomy is the first step in shifting the discourse toward higher order levels of thinking and metacognition. Gustafson (2014) described #digitalpowerups as scaffolds for each level of the Bloom’s revised taxonomy action verbs. The importance of both choice and personalization as motivational factors is central to this strategy. Increased transparency related to the course and instructor’s goals and intentions can also be crucial for establishing trust in online instruction, which benefits student understanding and engagement with material (Kirschner, 2021; Lu et al., 2016).

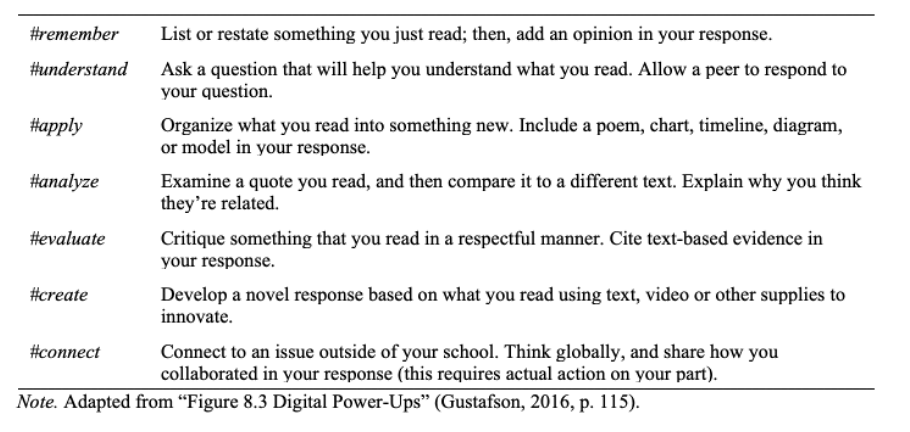

In SOC 3010, students are allowed to choose two to four of the powerups when they respond to prompts. In addition, students use additional powerups in comments to engage with peers. This second use of #digitalpowerups promotes thinking interdependently and encourages students to listen with understanding and empathy. Gustafson (2016) presented #digitalpowerups as badges students earned when engaging at the different levels of Bloom’s, and students included a code in their post. We adapted this so that students used the powerup verbs as labels or hashtags to structure and organize their discussion posts (e.g., #create). Figure 6.2 shows each #powerup and the corresponding prompts.

Figure 6.2

#Digitalpowerups for Online Discussions

The #digitalpowerups strategy builds on the features inherent in the discussion forum. First, this strategy harnesses a social media interaction space by introducing hashtags that serve as a reminder of the prompt being addressed. Second, #digitalpowerups serve as a tag (or label) to quickly indicate the level of Bloom’s that the students’ posts engage. Not only does the powerup indicate the level in which students are engaging (lower, mid, or higher), but also the prompts associated with the powerups scaffold or frame the student responses with Habits of Mind skills. Often students engage in the lower levels (#remember, #understand) of Bloom’s taxonomy based on the design and facilitation of the discussion (Gao et al., 2013), but the powerups nudge students into engaging in discussions in the mid-levels (#apply, #analyze, #evaluate) and the higher order levels as well (#create, #connect).

The Context of Social Inequality

Social Inequality is a 3000-level course required of undergraduate students in sociology-related fields at USU. This course examines social inequality at different levels using critical, analytical, and historical approaches. Throughout the course, we explore both current and historical frameworks for studying social inequity. This includes theories and research that illuminate how factors such as race, class, sexuality, and gender intersect in the lives of individuals. Upon completion, students emerge with a newfound set of skills that allow them to interpret the complex structure of social stratification with greater fluency. Students gain a deeper understanding of how sociologists define social stratification and the powerful role that ideology plays in upholding stratification systems.

Students examine how various historical, social, political, economic, cultural, and global forces create and perpetuate social inequality. Moreover, students gain the insight to appreciate the importance of ascriptive factors, including ancestry, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and religion, in determining an individual’s social status. In addition to distinguishing between absolute and relative definitions of poverty, students also recognize the significance of multiculturalism and diversity, both locally and globally. Throughout the semester, students engage in online discussions using the preassigned #digitalpowerups. Overall, 150 students from various backgrounds participated in the class over the 15-week semester it was offered.

Data and Data Collection

In Social Inequality, students must use #digitalpowerups to do their postings each week by engaging in lower levels (#remember, #understand), in mid-levels (#apply, #analyze, #evaluate), and in higher order levels (#create, #connect) of thinking. The student’s initial post includes three powerups and their comments to their peers should include two powerups. Using the powerups not only helps students structure their responses but also helps them to use it as a forum to interact and learn from one another. Typically, students will need at least two or three sentences to properly address each of the powerups they select, though some posts end up being several paragraphs.

In the rest of this chapter, we limit our analysis to students’ use of #digitalpowerups on topics related to gender and sexuality. After extracting and deidentifying postings from Canvas, we isolated 945 #digitalpowerups for gender and sexuality topics. In the following, we highlight how students used these powerups. We also analyze how students used the #digitalpowerups to demonstrate their thinking. Importantly, quoted text is abbreviated at times, though otherwise unaltered from its original. Grammatical errors are left unaltered to preserve the students’ voices and writing styles.

For instructors interested in incorporating #digitalpowerups in their courses, two prominent themes from our analysis appear useful in their relation to Habits of Mind. First, students used a variety of #powerups for the common purpose of normalizing vulnerability and reflexivity by highlighting their own growth and connecting course content to personal and secondary experiences. In these instances, students often demonstrated Habits of Mind like applying past knowledge to new situations, thinking about your thinking (metacognition), and listening and understanding with empathy. Second, in responses to their peers, students regularly engaged in a co-construction of knowledge through affirming, yes-and-ing, and pushing each other further. Here, Habits of Mind such as thinking interdependently, responding with wonder and awe, and striving for accuracy commonly emerged.

Normalizing Vulnerability and Reflexivity

The first overarching theme was the range of powerups used to show forms of vulnerability, including the acknowledgment of growth, the personal impact content had on a student, reflexivity, and positionality. In myriad ways, students made personal connections to course materials, evoked the experiences of friends and loved ones, and normalized discussions of their own learning in both original posts and responses. In relation to expressions of growth, some students framed their learning in relation to regret: “It pains me that I used to say this before I realized how harmful it is.” In this way students felt vulnerable enough to express personal experiences with growth. In one response to an #understand about how “your perception of sex and gender as a whole changed in the past 5 years,” one student felt comfortable enough to express that they “regret the reaction that I had when my sister came out as gay to me.” These statements not only reflect students’ thinking about their own thinking but also emphasize them remaining open to continuous learning, both of which appear aided by the comfort to be vulnerable with each other.

At the same time, this private and personal vulnerability emerged in relation to every #powerup and included both primary and secondary experiences. In one #apply post, a student composed a poem for “a close family friend who came out to me in confidence,” writing, “Who I am will even make those I love cry… So, one day, one day I pray / That who I am, will one day be ok.” These secondary experiences often represented both expressions of empathy and experiences that fostered new insights for students. For example, a student expressed that they realized how pervasive harassment can be when “several women were telling me they’re uncomfortable with guys at functions.” Another student questioned their family’s debate around “what to do about [their] gay aunt” and the “disgust” they felt about the unfairness of “hav[ing] to feel different because of the way they are simply born.” These examples show how students brought in past experiences of practicing empathy and understanding in ways that invited further empathy and understanding in discussion posts.

For others, vulnerability took the form of speaking about their own experiences, framing their positionality, and expressing reflexivity. Sometimes students posted about their experiences as a means of contextualizing course concepts for other students, representing the notion of brave spaces and taking responsible risks. One student opened up about the difficulty of supporting their girlfriend coming out to her parents and the shared feelings of rejection they both felt. Another student described the subtle ways they had been made aware of cultural expectations to conform to gender norms, writing, “I found it extremely irritating that the first thing he did when he met me was assume that I was tied to a man or had a brother whose footsteps to follow in [sic], and then assumed I was unsuccessful without one.” This reflexivity and application of past knowledge (or experiences) to new situations was often expressed in relation to examples of discrimination, such as assumptions “that I can’t do something because I’m a girl.” Similarly, another student reflected that their high school girls’ soccer team had been given less accessible training facilities despite being “consistently the best sports team.” Other students wrote poems with lines like “Dressed in clothes that I’m told you’ll like cause you’re a guy.” The blending of creativity, empathy, and critical thinking were common in posts that used #understand, #connect, and #apply to situate their experiences in the discussions.

Finally, students discussed their own positionality as a means of identifying and contextualizing their voices and opinions. For one student, this meant identifying their position as a “heterosexual woman” to contextualize the way they grappled with the discussions queer activists had about focusing on marriage equality “when marriage had historically been a way for men to exert power over women.” On occasion a few students also named their own queerness, along with the tensions between acceptance and the internalization of social norms, in discussion posts. What remains clear is that the presence of these vulnerable and reflexive expressions does not align with the use of any particular powerup. Students continually found ways to engage in meaningful conversations of growth about the self while using a range of #digitalpowerups that reinforced several Habits of Mind.

Co-Constructing Knowledge

The second trend noted throughout the content analysis grew from the comments and responses in student-to-student interactions that culminated in the co-construction of knowledge. In their responses, students overwhelmingly affirmed one another by stating their agreement, celebrating novel contributions, and responding with wonder and awe. These affirmations also went further by directly building on contributions in a practice of yes-and-ing and thinking interdependently. Finally, although not as common, students also strived for accuracy and pushed each other further on statements that either countered course material or were interpreted as missing the point.

Yes and Yes-and-ing

Throughout their discussion posts, students regularly showed empathy in their responses to affirm one another with an emphatic “Yes!” Often, these comments included expressions of gratitude and highlighted additions that students found useful for their own learning. Statements of the simple yet complete agreement were common. These included: “#remember I completely agree with you”; “#connect … I 100% agree that many topics are considered taboo or to [sic] uncomfortable to talk about”; “#apply I completely agree with your statement about women feeling obligated to leave their jobs after having a child”; and “#evaluate I agree with this statement.” While these responses range in specificity, the regularity of affirmation is significant in recognizing the positive framing original posts seem to receive in their feedback and the presence of awe among students.

Another subset of affirmations included explicit praise of the contributions made by original posts. For example, affectual framing looked like “#understand I love your question!” and “#analyze I’ve been wanting to watch that movie! That’s an amazing quote.” Similarly, while students celebrated each other’s perspectives, they also highlighted how original posts introduced new ways of thinking (or concepts) or reframed course material in ways that furthered their understanding of their own understanding. This included statements like “I never thought of it like that… just the terms ‘girlfriend’ or ‘husband’ can create a potentially false image for other people because similar to gender roles, these are also labels #remember” or “#apply…Thank you for making the timeline! It was super nice to be able to see the slow progression of gay marriage rights throughout the years.” Additionally, that effectual celebration can also be related to explicit thanks for peer-to-peer education and interdependent thinking as one student used both in their response:

I absolutely loved reading your discussion post! Your #apply graph really stood out to me. Reading statistics about this topic is one thing, but being able to visualize them really helped me understand this problem better. Thank you for educating me more about this topic!

Deeper levels of joint knowledge construction are evidenced in affirming statements where students would build on an original post by continuing a position or adding more nuance in the practice of yes-and-ing. One original post, for instance, quoted the textbook to refer to the social punishments for deviating from heteronormativity that make it too costly to explore alternatives. The student added: “#evaluate…I also know it’s not a choice…so society not ‘allowing it’ doesn’t keep it from happening.” In response, another student highlighted the critical framing of what is “allowed” and began with “I completely agree with your point here! …so society shouldn’t ‘not allow it.’ I think that is something society…needs to come to terms with to help all individuals feel safe and comfortable in their own environments and identities.” This practicing of building upon one another took place among the use of both lower level powerups like #understand as well as higher level thinking such as #analyze, #connect, and #create.

Pushing Further

While yes-and-ing was far more common than challenging or disagreeing with peers on the discussion board, there were still opportunities for students to push each other to more deeply engage inequalities related to gender and sexuality. At times this meant offering a different interpretation of course material. One student using #analyze disagreed with a video that seemed to say that “women shouldn’t speak up against [workplace inequality] and that men are the ones who should talk about it…I agree that men should talk about it, but I don’t think that women shouldn’t.” Another student offered a different framing: “I disagree that that was what she [the video] was saying. It was more of a ‘women cannot do this alone’ type of thing.” This reframing was a helpful example of students striving for accuracy among their peers in discussion posts.

Other times responses pointed out important omissions. One post focusing on “inequality for the LGBTQ+ community” in other countries asked what was “the best way to reduce and eliminate this inequality.” One of their peers responded with “#remember—Even in the United States, they [sic] are still treated unfairly in this country,” clarifying that the external focus seemed to imply an absence of inequality in the United States. This was like other response questions that asked for clarity as a means of highlighting an omission. For example, one student who used #connect compared the perspectives of their parents with their own experiences and concluded, “It seems like the conversation [of normalizing queerness] is almost new.” Another student responded by first agreeing that there are generational differences. But the student followed up with two clarifying questions to illuminate the difference between the presence of a conversation and its normalcy. “I’m wondering what conversation you are referring to in your last sentence?” the student asked. “And is it really a NEW conversation or just a more acceptable conversation?” In this way, the student demonstrated a willingness to address and challenge statements made by their classmates in ways that incorporated Habits of Mind like questioning and posing problems and striving for accuracy.

However, most often posts that countered course content were left without a response. This may reflect an aversion to conflict in institutional settings as well as a trend where antagonistic comments were primarily responses to original posts. These responses rarely received their own responses. For example, some students sarcastically invoked “trigger warnings”; claimed that “XX, XY is all there is on a scientific level”; insisted that “we aren’t blobs of flesh than can morph from male to female or any made-up thing in between”; wrote that “there are too many pronouns to remember”; penned that “there are fundamental physical and temperament differences [between men and women]. This is scientifically true”; or held that lawsuits surrounding sexism in the workplace are “manipulative” and “playing the ‘woman-card.’” Each of these examples were responses to original posts of several different #powerups, and the lack of peer engagement may be due to the structure of the discussion forum since students only have to respond to original posts and not responses.

Even when original posts that countered course topics receive responses, those responses often focus on different #powerups in the original post. Despite these potentially missed opportunities, the responses to original posts presented varying forms of co-constructed knowledge. Students built from basic affirmation and agreement to yes-and-ing, and they also pushed their classmates to strive for accuracy.

Discussion

Throughout the analysis, the themes of normalizing vulnerability and reflexivity and the co-construction of knowledge and understanding stood out as significant. The most prominent finding of this research, however, is how students used #digitalpowerups in ways that they were not originally intended. This is not a condemnation of powerups; rather, it reflects students being active participants in the structure of online discussions. To be clear, the analysis of these discussions has not been focused on causal relationships between powerups and higher or lower order thinking and discourse but instead an examination of how students used these categorical structures to organize their discussions of course material. What it has shown is that #digitalpowerups can be one tool for educators in facilitating discussions that situate students as agents in their own learning and in developing several Habits of Mind. Students can accomplish this by normalizing their growth, invoking personal and intimate experiences, and mutually reinforcing, strengthening, and pushing each other further in the process.

For educators interested in implementing powerups in online discussion boards, several key takeaways appear worth further discussion. First, in recognizing that powerups were not always used as intended, educators looking for more standardized measures of different orders of thinking may want to elaborate and specify the conceptual differences between powerups. Assigning different points for higher and lower order powerups may be one possible tactic. Others may wish to provide these existing powerups as options while emphasizing that students can use them as they see fit. Another option may be to encourage students to make their own powerups. Regardless, students should be familiar with the goals of this exercise, as there may be unrealized opportunities to pose meaningful questions for the sake of conforming to the assignment.

Second, our analysis was complicated by the varying uses of these powerups. Like findings from Thurston (2020), students used #remember differently than the instructor had intended. Some responses failed to include a powerup at all, and most response posts used the powerup only to identify which part of the original post they were responding to (i.e., in response to your #remember…). Only a handful used a powerup as an active response (i.e., #evaluating a #remember). If the goal is to invite students to engage original posts with varying orders of thinking and discourse, the development of a subset of powerup responses may be beneficial. These may include the patterns identified in this analysis like #Yes and #YesAnd as well as #YesBut, #Clarify, or #Alternatively to challenge classmates’ perspectives.

Third, finding ways that encourage continued dialogue beyond the original post and response could be crucial for deeper and more nuanced discussion forums. This recognizes that students rarely countered or objected to course ideas in their original posts. Instead, they opted to include these sometimes-antagonistic perspectives in responses, which were left without engagement. To be clear, when comments in online course discussion boards rise to the level of reinforcing the legitimacy of harmful inequality, instructor intervention is appropriate to preserve a safe space. However, given that students did include both countering and contributive perspectives in their responses and comments, finding ways that encourage further discussion may aid the potential for co-constructive knowledge and interdependent thinking.

Finally, the analysis in this chapter sought to highlight only a few positive ways that #digitalpowerups were implemented. It should be noted that not only are there numerous other unnamed patterns left unexamined here, but there are also several enduring limitations of online discussion boards that may not be explicitly clear. There remains a pattern of basic engagement or what may be seen as “doing the bare minimum.” As such, powerups do not necessarily eliminate the check-mark style of response. Additionally, some exceptionally well-written and thoughtful original posts were left without responses and engagement. Often, these posts were some of the last to be submitted, while others may have been unnoticed in a long stream of text. To counter this lingering challenge, educators may want to explore alternative structures to formatting the order of responses (i.e., randomly generated orders), incentivizing comments or likes on posts without responses, requiring original posts to be submitted earlier in the week and responses later in the week, or implementing more elastic #PowerupResponses.

Conclusion

This chapter offers insight into using #digitalpowerups in online discussion boards. We argue that these powerups provide students a safe and brave space to dive into potentially controversial topics, such as issues of gender and sexuality, in an undergraduate sociology course. We also see the use of powerups as complementary to several Habits of Mind, such as applying past knowledge to new situations, thinking about your thinking (metacognition), listening and understanding with empathy, thinking interdependently, responding with wonder and awe, and striving for accuracy. As the Covid-19 pandemic forced educators to switch methodologies from traditional classroom settings to online settings, many of us found ourselves exploring more inclusive and innovative teaching practices to implement. Social Inequality seemed to be a fitting course for incorporating #digitalpowerups in online student discussion boards.

In addition to the issues related to implementation of #digitalpowerups in online settings, educators are now faced with the authenticity of student discussion posts. As artificial intelligence tools (i.e., ChatGPT) become more accessible, educators have become concerned about the authenticity of student work. Integrating #digitalpowerups provides a creative opportunity for students to express their opinions in a safe and brave space. This pedagogical approach to discussions further encourages students to exercise their own voice in online discussions. We believe giving students the opportunity to choose and voice their opinions by implementing preexisting #digitalpowerups or empowering them to come up with their own #powerups will encourage them to be the authentic persons that they are. Empowering and incentivizing an authentic presence in the classroom regardless of the delivery of the content will then create an environment for meaningful contributions, putting critical-thinking skills to work and creating Habits of Mind that will help students become lifelong learners.

References

Allen, I. E., Seaman, J., Poulin, R., & Straut, T. T. (2016). Online report card: Tracking online education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group, LLC.

Al-Zakri, M. I., & Al-Jubair, T. K. (2020). Design of an educational program based on knowledge construction and its effectiveness in developing the productive habits of mind among female university students. Journal of Educational & Psychological Sciences, 21(2).

Andresen, M. A. (2009). Asynchronous discussion forums: Success factors, outcomes, assessments, and limitations. Educational Technology & Society, 12(1), 249–257.

Baglione, S., & Nastanski, M. (2007). The superiority of online discussions: Faculty perceptions. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 8(2), 139–150.

Cheung, W. S., Hew, K. F., & Ng, C. S. L. (2008). Toward an understanding of why students contribute in asynchronous online discussions. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 38(1), 29–50.

Cho, M. H., & Cho, Y. (2016). Online instructors’ use of scaffolding strategies to promote interactions: A scale development study. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(6), 108–120.

Christopher, M. M., Thomas, J. A., & Tallent‐Runnels, M. K. (2004). Raising the bar: Encouraging high level thinking in online discussion forums. Roeper Review, 26(3), 166–171.

Costa, A. L., & Kallick, B. (2009). Habits of Mind across the curriculum: Practice and creative strategies for teachers. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Darabi, A., Arrastia, M. C., Nelson, D. W., Cornille, T., & Liang, X. (2011). Cognitive presence in asynchronous online learning: A comparison of four discussion strategies. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27(3), 216–227. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00392.x

Ertmer, P. A., Sadaf, A., & Ertmer, D. J. (2011). Student-content interactions in online courses: The role of question prompts in facilitating higher-level engagement with course content. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 23(2–3), 157–186.

Gao, F., Zhang, T., & Franklin, T. (2013). Designing asynchronous online discussion environments: Recent progress and possible future directions. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(3), 469–483.

Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Fung, T. S. (2010). Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive and social presence: Student perceptions of the community of inquiry framework. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1–2), 31–36.

Gilbert, P. K., & Dabbagh, N. (2005). How to structure online discussions for meaningful discourse: A case study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 36(1), 5–18.

Gustafson, B. (2014, March 28). Power-up digital learning. Adjusting Course. https://adjustingcourse.wordpress.com/2014/03/28/power-up-digital-learning/.

Gustafson, B. (2016). Renegade leadership: Creating innovative schools for digital-age students. Corwin Press.

Hay, A., Peltier, J. W., & Drago, W. A. (2004). Reflective learning and on-line management education: A comparison of traditional and on-line MBA students. Strategic Change, 13(4), 169–182.

Herman, J., & Nilson, L. (2018). Creating engaging discussions: Strategies for “avoiding crickets” in any size classroom and online. Stylus.

Joksimović, S., Gašević, D., Kovanović, V., Riecke, B. E., & Hatala, M. (2015). Social presence in online discussions as a process predictor of academic performance. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 31(6), 638–654.

Kirschner, J. (2021). Transparency in online pedagogy: A critical analysis of changing modalities. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 76(4), 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/10776958211022485

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212–218.

Lambiase, J. J. (2010). Hanging by a thread: Topic development and death in an online discussion of breaking news. Language at Internet, 7(1), 1–22. https://www.languageatinternet.org/articles/2010/2814

Lee, E., Pate, J. A., & Cozart, D. (2015). Autonomy support for online students. TechTrends, 59(4), 54–61.

Lu, B., Fan, W., & Zhou, M. (2016). Social presence, trust, and social commerce purchase intention: An empirical research. Computers in Human Behavior, 56, 225–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.057

Mardi, F. (2020). Using think alouds and digital powerups to embed computational thinking concepts while in-service teachers reflect on a math solution design project. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 36(4), 237–249.

Mardi, F. (2022). Providing rigour, differentiation, and sense of community using a three-pronged VoiceThread discussion strategy during the pandemic. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 31(5), 637–654.

Moore, M. (2021). Asynchronous discussions for first-year writers and beyond: Thinking outside the PPR (prompt, post, reply) box. In Thurston, T. N., Lundstrom, K., & González, C. (Eds.), Resilient pedagogy: Practical teaching strategies to overcome distance, disruption, and distraction (pp. 240–259). Utah State University. https://doi.org/10.26079/a516-fb24

Murphy, M. K., Soyer, M., & Martinez-Cola, M. (2020). Fostering “brave spaces” for exploring perceptions of marginalized groups through reflexive writing. Communication Teacher, 35(1), 7–11.

Pacansky-Brock, M. (2012). Best practices for teaching with emerging technologies. Routledge.

Reeve, J., & Jang, H. (2006). What teachers say and do to support students’ autonomy during a learning activity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.209

Thurston, T. N. (2020). Architecture of engagement: Autonomy-supportive leadership for instructional improvement [Doctoral dissertation, Utah State University].

Valcke, M., De Wever, B., Zhu, C., & Deed, C. (2009). Supporting active cognitive processing in collaborative groups: The potential of Bloom’s taxonomy as a labeling tool. The Internet and Higher Education, 12(3), 165–172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.08.003

Whiteley, T. R. (2014). Using the socratic method and bloom’s taxonomy of the cognitive domain to enhance online discussion, critical thinking, and student learning. Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, 33, 65–70.