22 Developing Classroom Management Skills: Leveraging Habits of Mind in Pre-Service Teacher Education

Rachel K. Turner

Classroom management plays a major role in teacher retention and attrition within elementary schools. Researchers suggest classroom-management issues are one of the leading causes for teachers leaving the education field (Ingersoll & Smith, 2003) and are one of the leading struggles reported by teachers past and present (Langdon & Vesper, 2000; Goodwin, 2012; Phi Delta Kappan, 2019). Not unexpectedly, classroom management tends to be a leading cause for concern for pre-service and new teachers as well (Bromfield, 2006; Evertson & Weinstein, 2006; Sowell, 2017; Uribe-Zarain et al., 2019). Classroom-management skills must be developed to keep teachers within the profession.

Effective classroom management benefits both students and teachers. Researchers found that students whose teachers were trained in classroom-management programs led to “positive difference in social skills, adaptation to school, school achievement, and parental involvement in education” (Seabra-Santos et al., 2022, p. 1078). Additionally, Caldarella et al. (2023) found that as praise to reprimand ratios increased so did on-task behavior and grades for students at risk. They also reported that disruptive behaviors for some students, such as those at risk for emotional disorders, decreased (Caldarella et al., 2023). These results indicate a teacher’s classroom-management skills can influence not only student achievement but behavior and social skills.

The following chapter focuses on in-class activities and assignments used to facilitate understanding of the areas of classroom management. These areas include building relationships with students, finding solutions to problems, dealing with student behavior, and exploring educational inequities. The activities discussed allow my students—pre-service teachers—to interact with and develop a variety of Habits of Minds, including but not limited to listening with understanding and empathy, thinking flexibly, managing impulsivity, and thinking and communicating with clarity and precision. Additionally, as these pre-service teachers will be entering a diverse classroom makeup in their first classrooms, using Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (CRP) and Habits of Mind allows pre-service educators to better understand the needs of their students.

The Need for Classroom Management in Pre-Service Teacher Education

Beginning teachers find student discipline a serious challenge (Evertson & Weinstein, 2006), leading to the top reason teachers leave the field (Thibodeaux et al., 2015). It is well documented that teacher burnout is highly influenced by student discipline problems (Evertson & Weinstein, 2006; Ingersoll & Smith, 2003). Pre-service teachers tend to be apprehensive about classroom management in their future classrooms (Atici, 2007; Bromfield, 2006; Evertson & Weinstein, 2006; Sowell, 2017; Uribe-Zarain et al., 2019).

When asked what classroom management is, almost half of the pre-service teachers in my ELED 5105: Classroom Management & Motivation class respond with answers around discipline and student behavior. But classroom management encompasses much more than discipline. Classroom management is “to establish and sustain an orderly environment so students can engage in meaningful academic learning…[and] to enhance students’ social and moral growth” (Evertson & Weinstein, 2006, p. 4). Each of these areas are included in my classroom management course, with a particular emphasis on CRP.

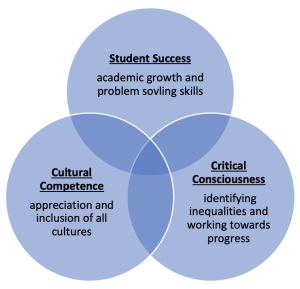

Culturally Relevant Pedagogy

Culturally relevant pedagogy is defined by Ladson-Billings (1995) as a critical pedagogy that is “specifically committed to collective, not merely individual empowerment” (p. 16). CRP includes three foundational criteria students should experience—student success, cultural competence, and critical consciousness (Ladson-Billings, 1995)—as seen in Figure 21.1. Teachers can help students be successful by building their academic skills, holding high standards for excellence, and engaging them in their own achievement (Ladson-Billings, 1995). Cultural competence allows students to “maintain some cultural integrity” (Ladson-Billings, 1995, p. 160). Teachers can use culture to engage and support students in their educational experiences, such as encouraging students’ use of native language, including parents and other community members in classroom learning to affirm cultural knowledge, and allowing students to bring cultural activities into the classroom. Critical consciousness helps students “develop a broader sociopolitical consciousness that allows them to critique the cultural norms, values, mores and institutions that produce and maintain inequalities” (Ladson-Billings, 1995, p. 162). In a classroom, this can look like critiquing knowledge represented in curricular materials or texts, analyzing systems of inequality, and solving problems in schools and communities.

Culturally relevant pedagogy can support effective classroom management in a variety of ways. The components of CRP focus on establishing positive relationships between teacher and student and strive to create a positive learning environment for all students (Ellerbrock et al., 2016). The use of CRP also helps teachers identify ways to engage all students through a variety of techniques including collaboration, self-reflection, and investigation of inequalities (Ellerbrock et al., 2016). While the components of CRP were designed to influence student growth, knowledge, and achievement, CRP can also support classroom management by helping students be successful, engage in cultural competence, and increase their critical consciousness.

Figure 21.1

Components of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy defined by Ladson-Billings (1995)

Context of the Course

Classroom Management & Motivation is a required course for all elementary education majors at Utah State University (USU). Before taking the course, students must be admitted to the Elementary Education program. Therefore, typically sophomores or juniors enroll in the course. The purpose of the course is to provide future teachers with the knowledge and skills needed to effectively manage classroom behavior as well as engage and motivate students. The course is designed to address the goals described in Figure 21.2.

Figure 21.2

Classroom Management & Motivation Course Goals

|

Goal |

Expectation |

|

1 |

Define and describe principles and procedures related to effective classroom management and school-wide behavior systems (i.e., how behavior is learned and reinforced at the individual, classroom, and school levels). |

|

2 |

Design classroom systems to prevent problem behavior and teach and reinforce appropriate behavior, including a) organizing and designing classrooms to prevent problem behavior, b) explicitly teaching appropriate behavior, and c) writing clear and appropriate classroom rules. |

|

3 |

Describe and evaluate class-wide engagement/motivational strategies, including a) techniques for keeping students on-task during a variety of classroom activities, b) effective instructional techniques to maximize student engagement, and c) the use of student interests and cultural diversity to increase cooperation and engagement. |

|

4 |

Learn to collaborate with colleagues, parents, students, and community leaders to develop school-wide discipline policies and a safe-school program. |

|

5 |

Develop strategies for the inclusion and accommodation of students with disabilities and students for whom English is not a first language that enhance the cooperation and student engagement of all students (i.e., methods of differentiating behavioral supports, appropriate accommodations to support students with greater behavioral needs). |

|

6 |

Recognize and accommodate for children’s development when responding to their behavior. |

While some educator preparation courses require a field placement component where pre-service teachers spend time in a local elementary classroom, Classroom Management & Motivation does not. This means my students are not always able to practice or apply the management skills they are learning in the course; that is, unless they currently work in a school setting as an aide, which some of them do. Research shows that pre-service teachers perceive field placements and student teaching as the most influential aspect of their teacher preparation programming (Wilson et al., 2001).

My Approach to Classroom Management

As an instructor, I strive to build educative experiences for my students that allow them to make sense of their own learning. I view myself as a facilitator who provides opportunities for my students to discuss and practice what they learn in new and engaging ways. In 2022, I restructured Classroom Management & Motivation around the three components of CRP, including student learning, cultural competence, and critical consciousness (Ladson-Billings, 1995). Within each of these components, I designed activities that correspond with course goals and objectives. When reviewing these activities, four Habits of Mind are integral to course activities centered around CRP: listening with understanding and empathy, thinking flexibly, managing impulsivity, and thinking and communicating with clarity and precision. An important note is that each activity described below was done within the Classroom Management & Motivation course between myself and my pre-service teachers. These activities also served as models for the pre-service teachers to implement CRP in their future classrooms.

Listening With Understanding and Empathy

An essential Habit of Mind for future teachers to develop is the ability to listen with understanding and empathy. Since many future teachers will work with students from different backgrounds and experiences, developing what Costa & Kallick (2000) describe as understanding one’s own thoughts and responses while also considering others’ thoughts and responses is imperative. To listen with understanding and empathy, teachers can pause to ensure they listen entirely to the other person, paraphrase what they heard to ensure understanding, and probe by asking questions to clarify or better understand (Costa et al., 2022). Through listening with understanding with empathy, teachers better understand their students’ needs and experiences while simultaneously modeling effective behavior for their students.

To allow pre-service teachers to practice this Habit of Mind, during the second week of class and in small groups, students discuss both positive and negative examples they have experienced around student misbehavior and teacher response. For some students this may include seeing a teacher yell at a student or get angry. For others those experiences directly involve themselves as the students. No student is forced to share an experience they do not feel comfortable sharing.

Through the experience, pre-service teachers practice listening with understanding and empathy. Prior to the discussion we talk about how these experiences may be hard to share or listen to. We also brainstorm appropriate responses that they can use to respond to their peers in appropriate ways and what it means to actively listen. We also collaboratively set norms for our sharing experience, which typically include aspects such as no interrupting, consider the other person’s thoughts and feelings, and plan your words before speaking.

Thinking Flexibly

Related to listening with understanding and empathy, the ability to reach beyond typical problem-solving methods and try new ways of thinking is what Costa & Kallick (2000) describe as “thinking flexibly.” This requires an open mind and willingness to try new things. Thinking flexibly also involves listening to others’ points of view (Costa & Kallick, 2000) while allowing for understanding of cultural differences. As future teachers of diverse classrooms, pre-service teachers are likely to be exposed to students with traumatic experiences. To think flexibly, teachers can gather and consider various points of view or perspectives, reflect on the overall goal, and consider shifting their actions or thinking processes (Costa et al., 2022). Teachers also can try to consider the emotions behind another’s point of view or experience (Costa et al., 2021).

Thinking flexibly works in conjuncture with listening with understanding and empathy. Listening to student experiences and striving to understand student behavior is essential as a teacher builds positive experiences for students. That provides the foundation for being able to think flexibly about how to support students.

I can also model additional ways for instructors to think flexibly. To support student success, for instance, I have learned to think flexibly with assignments and due dates. I allow students to turn in assignments as they complete them rather than based on a due date. In the syllabus I create an outline of projected due dates to allow students to work on assignments as the content is covered. Students do not have points taken off any assignment that is not due at that time and can therefore turn in assignments any time during the semester. There are instances, such as the Classroom Management Toolbox Draft, where students have a date that their assignment needs to be turned in to ensure my feedback. The ability to turn in assignments at any time also supports students’ cultural competence, as students may have days of religious observance or cultural activities. Rather than setting an arbitrary date that may not work for their schedules, I allow students to determine that for themselves. In addition, in class we discuss the idea of due dates in regard to homework. We discuss questions such as: Why do teachers enact due dates? Why do teachers assign homework? How is homework beneficial to students or not? What problems arise within assigning homework? These questions allow us to discuss questions around equality. Through this we are engaging in critical consciousness by addressing school norms that may not benefit all students.

I also facilitate pre-service teachers as they are building the Habit of Mind of thinking flexibly with scenarios in the classroom-management course. The use of scenarios supports student learning as they take previously learned theories and practice solving problems based on real-life situations. For example, when discussing setting up classroom procedures, I provide the scenario of a teacher who is having difficulties with students spending too much time on non-academic tasks such as sharpening pencils. The pre-service teachers work together to think flexibly about the problem. They brainstorm why the students may be taking their time and what problems that may cause. Then they come up with an action plan, a classroom procedure that would allow students to complete the task without taking time away from academics.

As a class we practice cultural competence by discussing the need for culturally relevant pedagogy. We spend a week learning what CRP is and how to enact it in classrooms. We practice cultural competence and critical consciousness through scenarios as well. For example, when discussing disruptive behaviors in the classroom, I present students with scenarios in the form of written examples, dialogue, and video. After examining the evidence, students must first make predictions about why the students are acting the way they are. Additionally, they investigate what biases or cultural differences may be influencing the student’s and/or teacher’s behavior within the scenario. This allows the pre-service teachers to explore not only cultural differences but also educational inequalities that may be playing a factor in the scenarios.

Managing Impulsivity

Managing impulsivity requires the ability to consider actions and words thoughtfully and deliberately (Costa & Kallick, 2000). Prior to acting, developing a plan or working through an issue can better prepare teachers to make more informed decisions (Costa & Kallick, 2000). To manage impulsivity, teachers can remain calm while thoughtful and deliberate in their decisions and actions (Costa et al., 2022). This helps ensure positive interactions between teachers and students.

I model managing impulsivity by creating detailed action plans for each week’s lessons. Because we talk about difficult topics such as childhood trauma and students’ emotional challenges, I want to ensure I have a plan for what activities we will do and how I will discuss these topics with pre-service teachers. Additionally, we practice scenarios around teacher frustrations where pre-service teachers can practice managing impulses.

Managing impulsivity works in conjunction with listening with understanding and empathy. Teachers deal with frustrating behaviors that can lead to impulsive reactions. I share with my students an experience I had when teaching elementary school. When teaching third grade, I had a student who struggled with maintaining control over asking questions. While I did not want to hamper his enthusiasm and curiosity, it became frustrating while teaching and supporting an entire classroom. I could feel myself getting frustrated and short with this student.

After reflecting on the situation, I sat down with the student, and we came up with a way to better deal with our questions and a better system for me to answer his questions. We created a chart that allowed him to evaluate the type of question he had and some action plans prior to coming to me. For example, if he had a question about assignment instructions, he had to ask at least two other students prior to asking me. Not only did this help the student build a process for dealing with his own impulsivity but it also helped me to listen with understanding and empathy when he approached me with his questions. This interaction helped the student become more successful and created a more positive learning space for him, critical to culturally relevant pedagogy.

Communicating With Clarity and Precision

Another important Habit of Mind that we practice is communicating with clarity and precision. This includes communicating accurately in written and oral forms (Costa & Kallick, 2000). To communicate clearly and precisely, it is important to avoid overgeneralizations, distortions, deletions, and exaggerations (Costa et al., 2021). Teachers must communicate with clarity and precision for students to understand content and instructions as well as build meaningful relationships with students.

One of the areas that pre-service teachers tend to be nervous about is interacting with parents and families. Whether through parent conferences or daily communication, this can be a stressful area for new teachers to navigate. Building the skill of communicating with clarity and precision is foundational for teachers as they interact with parents and families.

In the course, the pre-service teachers do multiple activities around parental and student communication. One of their graded assignments is to write a letter (or newsletter) they would send to students and parents welcoming them to their classroom. Their letter must be professional and in an easily accessible format while also including the following components:

- Information about themselves and their experience with teaching

- How they plan to build classroom community

- How they plan to meet students’ individual needs

- What types of activities they might see in their classroom

In class, pre-service teachers work together to plan how they will address each of these components. Thinking through their explanations helps them with clarity in their writing as well as managing impulsivity. Moreover, they peer-review each other’s writing to ensure clarity and accuracy of information.

Another activity that pre-service teachers engage in is brainstorming classroom procedures that need to be addressed within their first few weeks of teaching. Procedures such as how to sharpen your pencil, where your backpacks and school items are placed, how to ask questions, and when to leave the classroom are just a few of many procedures that teachers teach students to ensure an efficient classroom. I model for my pre-service teachers the process of creating procedures for one classroom activity, such as entering the classroom in the morning. We break it down into parts, including how to enter the classroom, when to enter the classroom, and where to place backpacks. This helps the pre-service teachers understand how important it is to speak and develop clear expectations for students.

Conclusion

Classroom management plays a major role in teacher attrition, and as such, it is essential that quality classroom-management courses are included within teacher-preparation programs. As pre-service teachers will be entering diverse classrooms, culturally relevant pedagogy can support their understanding of students as well as student success. Using practices from the Habits of Mind framework, including listening with understanding and empathy, thinking flexibly, managing impulsivity, and thinking and communicating with clarity and precision, pre-service teachers will be better prepared to serve their diverse student populations.

References

Atici, M. (2007). A small‐scale study on student teachers’ perceptions of classroom management and methods for dealing with misbehavior. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 12(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632750601135881

Bromfield, C. (2006). PGCE secondary trainee teachers and effective behavior management: An evaluation and commentary. Support for Learning, 21(4), 188–193.

Caldarella, P., Ross, R. A. A., Williams, L., & Wills, H .P. (2023). Effects of middle school teachers’ praise-to-reprimand ratios on students’ classroom behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 25(1), 28–40.

Costa, A., & Kallick, B. (Eds.) (2000). Discovering and exploring Habits of minM. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Costa, A., Kallick, B., & Zmuda, A. (2021). Building a culture of efficacy with Habits of Mind. Educational Leadership, 79(3), 57–62.

Costa, A., Kallick, B., & Zmuda, A. (2022). Teachers: Habits of Mind explanations. The Institute for Habits of Mind. http://www.habitsofmindinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Teacher-HOM-Explanation-1.pdf

Ellerbrock, C. R., Cruz, B. C., Vásquez, A., & Howes, E. V. (2016). Preparing culturally responsive teachers: Effective practices in teacher education. Action in Teacher Education, 38(3), 226–239.

Evertson, C. M., & Weinstein, C. S. (2006). Field of inquiry. In C. Evertson & C. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 3–51). Routledge.

Goodwin, B. (2012). Research says new teachers face three common challenges. Educational Leadership, 69(8), 84–85.

Ingersoll, R. M., & Smith, T. M. (2003). The wrong solution to the teacher shortage. Educational Leadership, 60(8), 30–33.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995a). Towards a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(2), 465–491.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995b). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 159–165.

Langdon, C. A., & Vesper, N. (2000). The sixth Phi Delta Kappa poll of teacher attitudes towards the public schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 81(8), 607–611.

Phi Delta Kappan. (2019). Frustration in the schools: Teachers speak out on pay, funding, and feeling valued 51st Annual PDK Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward the Public Schools. The Phi Delta Kappan, 101(1), K1–K24.

Seabra-Santos, M., Major, S., Patras, J., Pereira, M., Pimentel, M., Baptista, E., Cruz, F., Santos, M., Homem, T., Azevedo, A. F., & Gaspar, M. F. (2022). Transition to primary school of children in economic disadvantage: Does a preschool teacher training program make a difference? Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(6), 1071–1081.

Sowell, M. (2017). Effective practices for mentoring beginning middle school teachers: Mentor’s perspectives. Clearing House, 90(4), 129–134.

Thibodeaux, A., Labbat, M., Lee, D., & Labbat, C. (2015). The effects of leadership and high-stakes testing on teacher retention. Academy of Educational Leadership, 19(1).

Uribe-Zarain, X., Liang, J., Sottile, J., & Watson, G. R. (2019). Differences in perceived issues in teacher preparation between first-year teachers and their principals. Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 31(4), 407–433.

Wilson, S. M., Floden, R., & Ferrini-Mundy, J. (2001). Teacher preparation research: Current knowledge, gaps, and recommendations. Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy, University of Washington.