8 Making Asynchronous Online Discussions Meaningful: An Introduction to The Pioneer Method with Robust Scaffolding

Matthew D. LaPlante

The students in my graduate cohort were motivated. Most were teachers with years of experience. Some had won national awards. Several were experts on working with at-risk learners. These were people who knew how to learn. Yet we were all struggling with our online classes.

We were not reluctant online learners. We had all been drawn to California State University East Bay’s Online Teaching and Learning program precisely because of our interest in this emerging modality. Our instructors were experts in their disciplines. The assignments were well related to the readings. We were following the assignment instructions, dutifully checking off each of the boxes labeled “mastery” on our instructors’ rubrics. And it was not at all an issue that my fellow students and I were spread out across the United States. In phone calls, chat groups, and the occasional grainy video calls (this was in 2009, a decade before the “Zoom Boom” of video conferencing), we built intellectual connections and lifelong friendships, even though many of us would not meet in person until graduation day.

So, what was the problem? Every class was largely centered around a set of questions that were to be answered and debated on an online discussion board. But the responses to these prompts never seemed to come close to mirroring the breadth and depth of conversations that happen in brick-and-mortar classrooms. They did not feel like a true academic discussion.

There are endless ways to characterize an effective discussion. In this chapter, I adhere to the definition for “true academic discussion” built upon prior research in traditional classrooms (Alvermann et al., 1987; Guzzetti, et al., 1993) in which student voices dominate, students interact with one another, students contemplatively communicate, and students are expected to provide evidence to support what they are discussing. I will further suggest that a true academic discussion is the heart of a pedagogy that prioritizes voice, co-creation, social construction, and self-discovery through the employment of the learning dispositions known as the Habits of Mind (Kallick & Zmuda, 2017). In particular, the Habits of listening with understanding and empathy, questioning and posing problems, thinking and communicating with clarity and precision, striving for accuracy, and thinking interdependently are key in discussions that promote depth and meaning.

Alas, it did not feel like these things were happening in the discussions in our classes. These discussions were most active on the first and last days of the period, with little activity happening in between. The asynchrony made it hard to track and follow any single theme. There was a lot of cheerleading (“Good point, Deb!”) and not a lot of contemplative debate, let alone the reflective, evidence-based kind of discourse that helps challenge rigid views and stoke new ideas (Oros, 2007). When our instructors engaged, any threads that were active at that point ended as we re-centered our efforts to address the professor.

For me, the promise of online learning—that well-designed virtual environments could become every bit as meaningful as brick-and-mortar classrooms while fulfilling the promise of expanding equity (Warschauer & Matuchniak, 2010)—seemed to be losing its luster.

The Best Practices

Early into my studies, I mentioned my concerns to one of my instructors. “It really does fail to live up to the promise,” she lamented, “but I don’t think anyone has figured out how to actually make it work.”

That was disheartening. This was an expert in online learning, admitting that a central element of her class was a bust—and shrugging it off because it was no more of a failure than the discussions happening in other online classes. Impudently, I challenged her. “Surely someone has stumbled upon some best practices, right?” I asked. “Yes,” she said, “and what we’re doing in this class are supposedly the best practices.”

As evidence, she directed me to what remains one of the most cited, and presumably emulated, examples of what a quality online discussion should look like, a model built on a case study at a large U.S. university from 1999 to 2001 (Gilbert & Dabbagh, 2004). The study population was similar in many ways to my cohort; the classes studied were iterations of a graduate course on instructional technology and learning theory. That seemed to be a promising start. But the classes evaluated in the study were not, in fact, fully online—the students and professor met face-to-face each week. As such, any successes of the Gilbert and Dabbagh model could not be separated from the hybrid nature of the classes in which they were taught. That did not mean these methods could not work in a fully asynchronous course, only that the case study did not offer any evidence that it would. Yet this was the structure my professor, and many others at our university at that time, had adopted. Each of these instructors had closely adhered to a protocol that included:

- Required participation.

- Web-based reading resources that explained the role of online teachers and learners.

- Student facilitators drawn assigned to lead discussions and an instructor-provided rubric of expectations for how to carry out that duty.

- A list of tips for successful online discourse for students.

- Guidelines about the frequency of posts.

These seemed like good guidelines. But, at least from my perspective, this structure did not create true academic discussions. When professors were involved, it was their voices that dominated, and when they were not, it was their proxy, the student facilitators, who directed the flow of the conversation. It was often unclear who students were interacting with, or if they were truly interacting or merely posting, as if on a physical bulletin board (a place where one leaves things for others to find, but not where one sticks around to interact with others). If students were indeed being contemplative, it seemed they were contemplating how to fit all rubric requirements into the shortest post possible. And lacking much, if any, guidance on how the assertions in a post should be backed, most students simply used their own personal experiences.

When I re-scrutinized the data from the Gilbert and Dabbagh paper, it was clear the model used did not do much to improve the quality of discussions in the classes that were part of the original case study. As that model was developed, the quantity of posts with a reference to the assigned readings doubled from 9% to 18%, but there was no significant improvement in the following: students’ personal interpretation of the content; the building of connections to prior knowledge or outside resources; the use of personal experience or application of knowledge in a “real word” context; the use of analogies, metaphors or philosophical interpretations; and the making of inferences that ascend the information that was provided. The model that my cohort’s instructors were using as “best practices” had not even been established, or claimed, to be successful practices by that study’s authors!

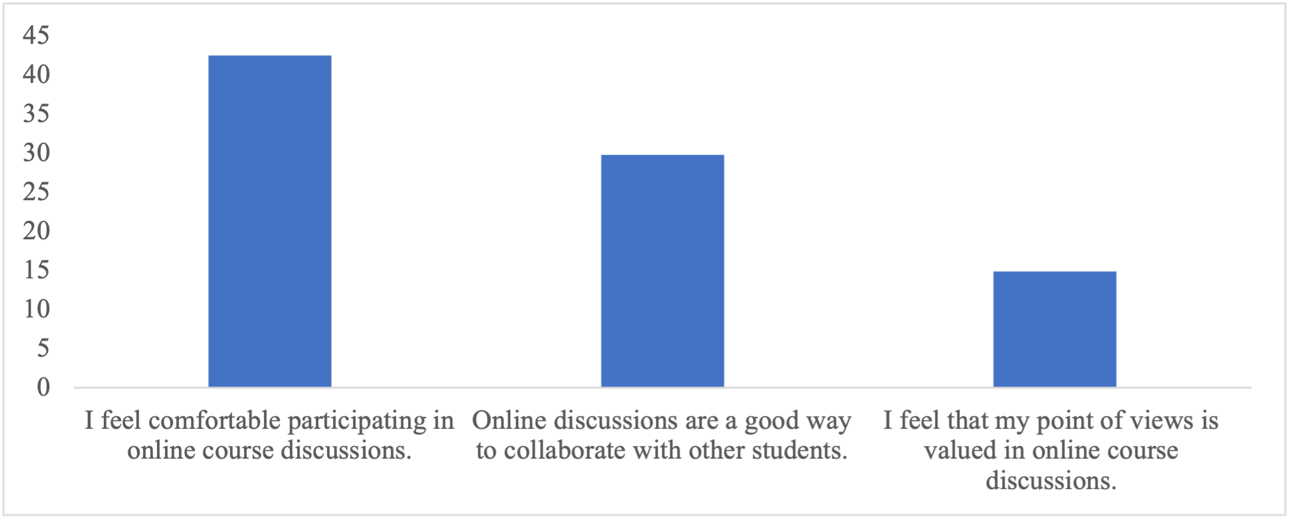

In 2010, in fulfillment of an assignment in a class on learning culture, four members of my cohort surveyed 47 other learners in five classes at our university. The survey was specifically designed to assess perspectives on online learning communities, but results from three specific questions felt indicative of the struggles I had experienced. While 42.6% of participants expressed strong agreement with the statement “I feel comfortable participating in course discussions,” only 29.8% indicated a similar level of belief that “online discussions are a good way to collaborate with fellow students.” An even smaller number, 14.9%, strongly agreed that “my point of view is valued in online course discussions” (Casey et al., 2010).

Figure 8.1

Percent of Students Indicating Strong Agreement

The survey revealed some degree of skepticism of the efficacy of online discussions as collaborative environments, a long-held central tenet of constructivist learning (Edelson et al., 1995). Only a small number of students were strongly confident that their contributions were valued by other learners, an essential element of a productive discussion and an indication that, if other students were indeed listening with understanding and empathy, those qualities were not well perceived by others. This, of course, was among learners who had self-selected into a program that was focused on online teaching and learning. I could not see how anyone could build new knowledge upon their own experiences if they did not strongly believe in the adequacy of the associated social discourse or if they were unsure that their contributions were valued.

A Selfish Pioneer

I feel tempted to say that I decided to change things for the better for everyone. Alas, I did not have that sort of moment of resolve. What I did have was a sense that I could at least make things better for myself—to create some structure for my own contributions that might help me get more from the discussions.

At the time, my biggest annoyance was the challenge I had tracking a theme across threads. Sometimes, for example, I would start working on a response to a post only to find that, by the time it was ready to be published, I was now responding to something that was three or four posts higher in the queue. Other times, I would read another student’s post and, for what were likely similar reasons, be unable to understand what part of the earlier discussion they were referencing. I suspected this was interfering with the rhythm of reciprocity that is characteristic of productive discussions. In response, I began directly quoting the relevant part of the post to which I was replying. That way, even if other learners did not see it sequentially, they would be able to easily understand the context. This was a self-serving rather than example-setting act. I craved the sorts of discussions I remembered having in my in-person undergraduate experience and wanted to lower the barriers that kept fellow students from choosing to respond to my posts. The easier I could make it for them to understand the point I was making, the more responses I would get.

Another of my concerns was that there were many posts in which participants would simply parrot other students’ answers, which did little to move the discussion forward, let alone reflect the sorts of questioning and interdependent formation of ideas essential to co-creation and social construction. Other times, they would make an assertion without citing evidence or, when they did offer evidence, it would be with the barest of indications of where it came from, a poor habit if clarity, precision, and accuracy are valued. While formal citations might have helped, they seemed awfully “clunky” as part of a discussion post. Fortunately, the binding of digital object identifiers to URLs had been in place for about a decade at that point (Liu, 2021) and was being widely adopted, such that hyperlinking to academic studies had become easy. So, I decided to only publish posts that included a hyperlink to some form of credible evidence.

Finally, to make sure there was always an easy way to move the discussion forward from my post, I ended my comment with an open-ended question related to whatever assertion I had made.

Altogether, these practices meant my posts began to look like this (fictionalized) example:

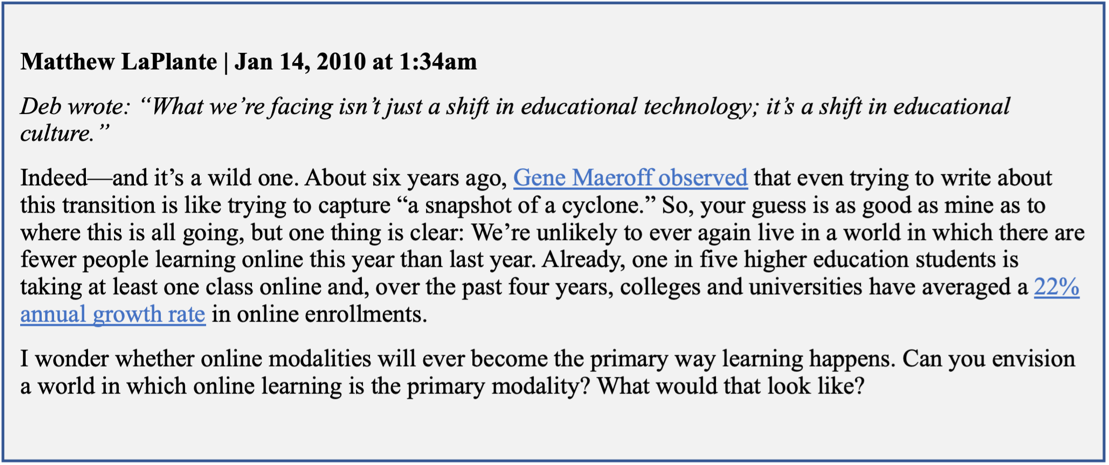

Admittedly, this was weird. For the first time since I was much younger, I was genuinely worried about what other students thought of me. And maybe some of them did think I was strange, but then something surprising happened: Several colleagues began adopting this method of posting. An educator from the Oakland School for the Arts, J. D. Cogmon, was the first person I can recall mirroring this tactic. A few others joined us before that class ended. By the time I graduated, many of the students in my cohort were using what I had started calling “The Pioneer Method,” a reference to Easy Bay’s mascot and to the fact that I was beginning to feel a little like a trailblazer in the Wild West of Online Discussions.

It seemed like this method was creating better discussions, but I could not know with any level of confidence whether that was truly the case. For one thing, I wanted it to work, so there was plenty of confirmation bias at play. For another, not everyone in the class used the Pioneer Method, and it was not clear whether students who did not intrinsically see its value would have improved their contributions to the discussion if they did adopt it.

The Pioneer Method Gets a Test

I envisioned the Pioneer Method as a model for discussions in purely online settings. So, when I got my first chance to teach, as an adjunct instructor for an in-person undergraduate writing class at Utah Valley University in the fall of 2010, I did not think I would have much use for it. After all, I developed this method to help make online discussions feel less inferior to in-person class conversations, which I had always considered to be inherently superior. But when I tried to foment an in-person class conversation, I was often met by blank stares. When a discussion would get going, it was often dominated by one or two voices. And although the class included students of color and a nearly even balance of genders, it seemed like two or three confident, young, white males were always the ones doing the talking. What is more, nearly every person who did talk would express an opinion devoid of evidence, and when asked to present evidence, they would often say something to the effect of “Well, that’s just my opinion.” In those first few weeks, something that should have been obvious to me all along became clear: The reason I was so enamored with the power of great in-person classroom discussions is that, during my career as a student, I had always been one of those very confident, young, white males. I had always been at the table, and I had not noticed who was not.

Among students, teachers, and researchers, it is no secret that the “everyday inequities” of pedagogical culture has long included the domination of male participants in classroom conversations (Hall & Sandler, 1982). Nearly 40 years after this “chilly classroom climate” was first described, it was revisited by researchers at Dartmouth College, who conducted nearly 100 hours of classroom observations and found that, on average, male students “occupy classroom sonic space” 1.6 times as often as women. “Men also speak out without raising hands, interrupt, and engage in prolonged conversations during class more than women students,” the researchers wrote. Other scholars have similarly studied how classroom discussion participation is impacted by age and race. In 1996 researchers from Purdue University reported on an apparent “consolidation of responsibility” for older students, who spoke more than younger ones (Howard et al., 1996). A decade later, scholars from the same institution reported on evidence that white students participated in classroom conversations at a higher rate than students of other races, who were primarily African American in the participating student group (Howard et al., 2006).

These are not the only factors impacting in-person discussion participation. Other reasons include introversion, shyness, language proficiency, cultural differences, bad experiences, peer pressure, knowledge, interest, and fear of failure (Zakrajsek, 2017). While it has long been recognized that neurodiversity also impacts in-person discussion participation, accommodation strategies have been unevenly applied (Burgstahler et al., 2015). Speech disorders can also be a profound barrier to in-person discussion participation; students with these disabilities are often confronted with implicit and even explicit evidence that their “excessive use of air time” is unwelcome (Daniels et al., 2011).

Participatory equity was certainly one of the reasons I implemented online discussions in the first in-person class I taught, and this continues to drive my enthusiasm for the community-building power of supplementary asynchronous conversations (Covelli, 2017). Admittedly, though, I was also pining for an opportunity to take the Pioneer Method “out for a spin.” So, in the second week of class, I introduced my students to the “quote, reflect with evidence, question” method I had experimented with in my own graduate studies.

It would not be long, however, before I realized that introducing students to the model would not suffice. Motivated learners picked it up quickly, followed it with fidelity, and certainly seemed to elevate their contributions as a result, but others struggled to adopt this additional learning framework, and I feared I might soon be doing as much “grading of rules” as I was grading of knowledge.

Challenges to Adoption

When I introduced my first college class to the Pioneer Method in 2010, about half of the students had previously participated in online academic discussions. Today, more than a decade later, it is uncommon to find a student without substantial experience in online discussions. Perhaps counterintuitively, this can be a significant challenge to adoption of the Pioneer Method because many students have well-developed habits around this part of their learning experience. They are often unpracticed at listening with understanding, questioning, communicating with clarity, striving for accuracy, and thinking interdependently.

I have come to recognize that, in no small part, the lack of these habits in online discussions stems from a tendency for students to only participate at the start or end of a discussion period, a result of students who are used to being held accountable to a quantity of posts, but not to a frequency of posts.

Another well-ingrained challenge comes from students who are used to online discussions being a place to share opinions, but not familiar with the process of connecting their beliefs or experiences to other forms of evidence. Whether in-person or online, though, good academic discussions are those that begin with study—and invoke the products of study—as they continue to evolve, and a well-balanced constructivism is one in which we honor the knowledge that students have before they even sign up for a class, but also celebrate—and hold them accountable for—the knowledge they offer as a product of their study during the class.

The strategies I use to support the Pioneer Method did not come to me all at once. Over the first decade of my teaching career, I taught more than 50 in-person class sections and more than 20 sections of fully online classes that have used this asynchronous discussion model, adjusting along the way. What follows represents my current practices.

Scaffolding for Success

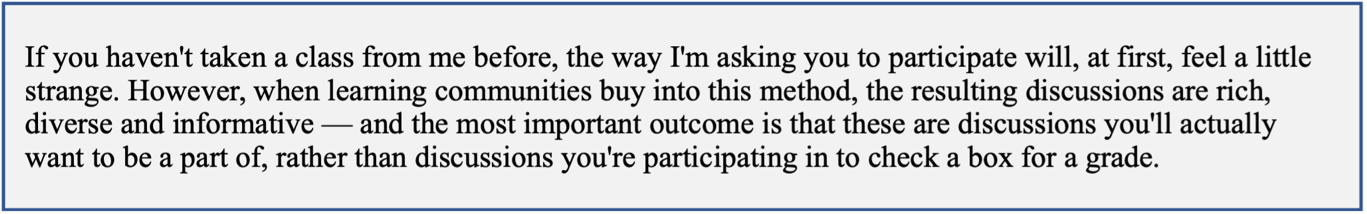

Because I am asking students to build new habits around discussions, I always make sure to explain why. For instance, this is the way I set up the introduction to the Pioneer Method:

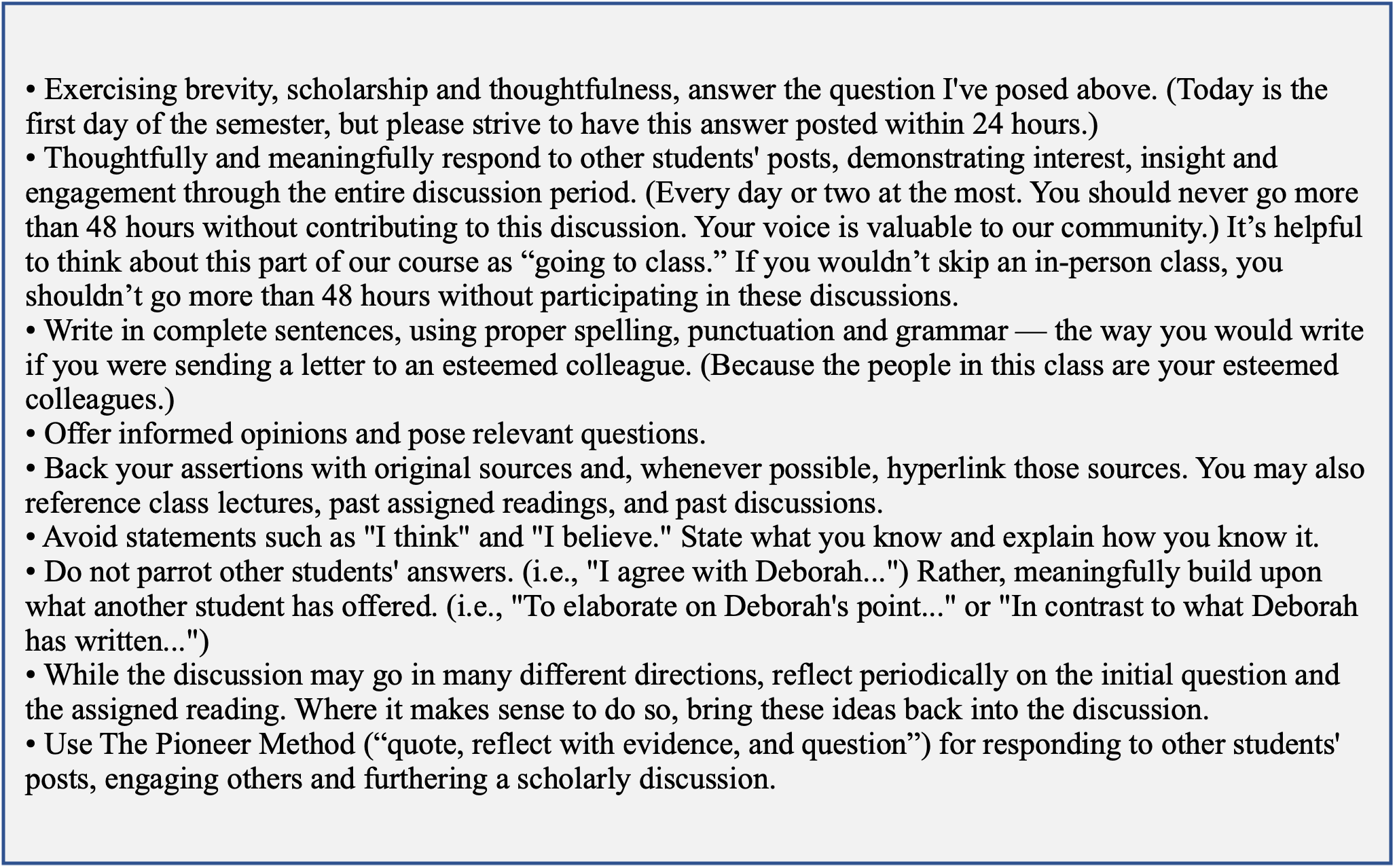

Next, I explain the rules. This is where I introduce the idea of “metering,” in which students are expected to post not a certain number of times but rather at a certain pace—in this case, “no less than every other day”:

Finally, I whimsically model the format. Here, for instance, is an example that uses characters from Star Wars:

This is a lot to take in, and I do not expect my students to be immediately perfect at using this structure. So, I employ multiple interventions.

On the first day, I strive to respond “in thread” to posts that do not follow the format. This allows the entire class to benefit from soft public correction.

On the second day, I send an all-class reminder about the discussion. Usually, most students have at least attempted a post at this point, and I accentuate this fact, leveraging the power of positively directed “herding.”

That evening, I check to see who has not yet posted, and I send them a direct message via the learning-management system.

About 3 days into the first discussion, I engage the power of social proof (de Bont, 2018), using a tactic often employed by K–12 teachers: redirection via public praise of positive examples. I also reemphasize the requirement to continue participating at a prescribed pace.

My final tactic for encouraging good participation habits before it impacts a student’s grade is a text message or call to learners who have not participated, not adhered to the prescribed pace, and/or are continuing to neglect the prescribed format. (In the introductory syllabus quiz at the start of the semester, I ask students permission to contact them in this way with “reminders, feedback, questions, and words of encouragement.”)

The next line of intervention comes from comprehensive feedback once the first discussion has been completed—and a grade that, for those who are still struggling, makes clear the consequences of nonparticipation.

It is not just struggling students who receive detailed feedback. Any student who does not receive full points gets an explanation as to what they could do to improve, which elevates the next discussion by giving top-performing students additional opportunities to demonstrate exceptional participation, leading the process of co-creation within the discussions.

This is a great deal of work, but I try to remember the history I am up against. We have thousands of years of experience with teachers physically standing before students at a set time each day and just a few decades of experience in an asynchronous online setting. Even given the meteoric rise in online learning, most students “learned to learn” in a traditional classroom setting. They need time to “learn to learn” in an online setting, too.

Once everyone buys into this method, though, a rhythm of participation takes over. In some semesters, I do not have to send any reminders after the second discussion assignment.

Writing the Prompt

Because a true academic discussion is student-centered—prioritizing self-discovery, co-creation, and social construction—I intervene only when I see a lack of civility or students appear to be confused about some aspect of the objectives. However, since my evaluations indicate that students appreciate the broad professional experience I bring to my teaching, I also seek to “send them off” on each new journey of discussion with a prompt that reflects on my own experiences as a writer. In these prompts, I try to model the sorts of things I want to see from my students, including personal vulnerability, a social-emotional demonstration of trust (Blaine, 2014). Each prompt includes the required reading and concludes with the question that each student will answer to begin their discussions, as evidenced in the following example:

And Away They Go

The discussion sparked by the above prompt included all 17 students who were enrolled in the class and spanned 81 total posts over 10 days.

In the Canvas learning-management system, instructors may select “users must post before seeing replies.” I prefer this limitation, as it appears to prevent “parroting” and it creates as many threads as there are students.

Each thread takes on its own personality and goes in sometimes unpredictable directions. A few die off after the first post; others keep going for the duration. Perhaps not surprisingly, I have found threads that begin with a weaker initial answer (one that does not offer contemplation backed with ample evidence) are often abandoned early in the discussion period. This does not prevent the original poster from having an impact on the discussion, because they can easily jump into any other thread.

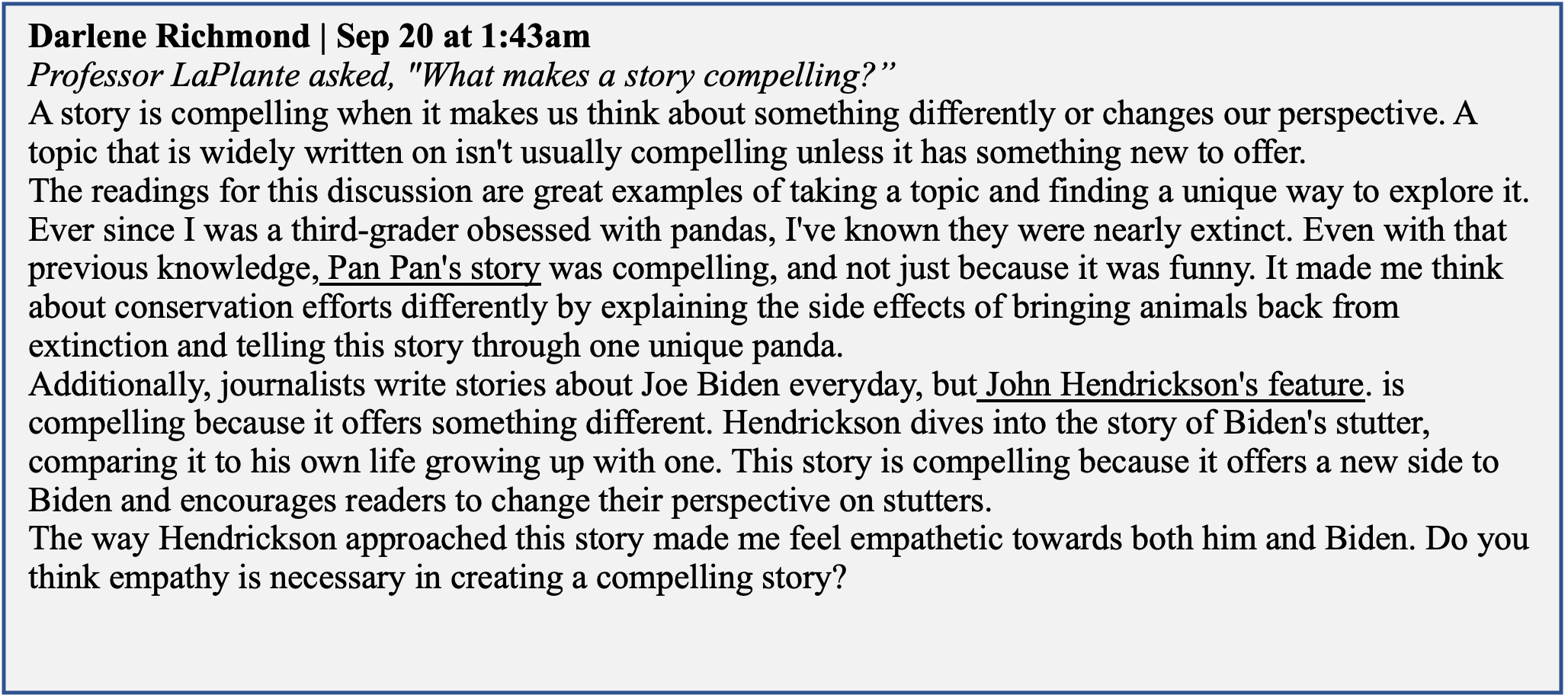

In the following thread, which began on the first required day of posting and continued for 8 days, the students made frequent use of the “shared currency” of the assigned readings as well as referencing other sources of meaningful information, their personal histories, earlier discussions, lectures, individual meetings with me, tools they are learning to use, skills they are building upon, and experiences they are having as they work on their course projects. While new posts usually build on the immediately preceding contribution, sometimes the students began their post with a reference to a comment made a few posts earlier in the queue. This often happens because students are working on answers at the same time in the asynchronous setting. But, because each post begins with a reference to the part of the discussion they are responding to, other students could immediately identify the context.

Assessing the Quality of a Discussion

One of the best parts of this job is learning from students, and I derive great joy from ideas such as the one Raley shared in the second post of this thread when she noted that even a president’s supporters see that person “as a president first, human second.” This is my admittedly subjective way of assessing whether a discussion is “good.” After all, I have used some of these prompts for more than 10 years. Having seen many hundreds of variations of responses, it stands to reason that if I am still learning new things, my students are as well.

I also look for signs of synthesis and social construction. Specifically, I ask myself: Are students building on ideas they have picked up in other parts of the class? Michelle’s September 21 post on using a “meta,” for instance, is a reference to a writing technique the students learned about earlier in the class. It is a concept that students often struggle with, and it was good to see them working through it together. As another example, on September 27, Taylor mentions the subject of an assignment she is working on for the class, bringing several parts of the learning experience into her response. And although I stay out of the fray, my presence does not completely disappear. Students often bring up a point from a lecture or something they learned in a meeting with me, as Ally did on September 26. These discussions often take on the qualities of a “moveable feast,” as myriad parts of the conversation are invoked and re-invoked along the way. To wit: On September 23, Maya answers a question asked by Darlene on September 20 but also references an observation made by Michelle on September 21, drawing from multiple parts of the ongoing conversation to make her point.

Every thread ultimately ends with an unanswered question. These are not wasted queries; they are great fodder to turn back upon the asker. When I met with Taylor after this discussion ended, for instance, I asked, “How did you go about creating the characters in your story?” Students are often well prepared for this, sometimes without realizing it. The act of asking a question seems to spawn a process of self-discovery. Indeed, Taylor told me about the successes he felt and the struggles he faced in bringing his subjects “to life.” He further explained the steps he was taking to improve his practices.

A more objective assessment of the quality of these discussions, however, goes back to the principles introduced at the beginning of this chapter. Did student voices dominate? Did they interact with one another? Did they contemplatively communicate? Did they present supportive evidence? Were they listening with understanding and empathy? Were they questioning and posing problems? Were they thinking and communicating with clarity and precision? Were they striving for accuracy? Were they thinking interdependently? In the case of this thread—and nearly every discussion I have watched unfold as students apply the Pioneer Method—I believe the answer to all these questions is “yes.” Online discussions that exhibit these characteristics are true academic discussions.

A Good IDEA

Given the role asynchronous discussions play in most online courses, it is unfortunate that my university does not have a student course evaluation metric that is specific to this part of the learning experience. But we may derive my students’ experiences with this model from their anonymous post-course comments and answers to scored questions on seemingly related topics. Since the spring of 2020, when I began teaching exclusively online, I have been the instructor of nearly 20 undergraduate classes that use the Pioneer Method. These classes are a mix of lower- and upper-division courses. Some have included all journalism majors and others are a mix of majors. (Several of the classes did not have enough course evaluation responses to merit quantitative assessment; only qualitative feedback from those courses is described below.)

The qualitative comments on the IDEA course evaluations for these classes reveal that not every student views the discussions favorably. A response from a student enrolled in a Public Affairs Reporting class in the spring of 2022, for instance, was particularly negative. “The discussions! Ah, they’re terrible,” the student lamented. “People just say dumb things and I don’t want to take time answering them.” In that same semester, a student enrolled in Sports Writing expressed a seemingly similar opinion: “Discussion boards are not good,” the student wrote. “They feel like busy work and an excuse for the professor to not lecture. I wasn’t taught anything in this class. I had to research it myself.”

While feedback like this can feel deflating, this last comment was not necessarily indicative that the discussions are not having their intended effect. In this case, I can affirm that “the professor” was indeed trying “to not lecture,” in order to allow student voices to dominate and self-discovery to prevail: These discussions were indeed intentionally devised to encourage students to engage in their own research using meaningful and credible sources. Likewise, in the fall of 2022, a student enrolled in Feature Writing suggested the discussions could have been “graded a bit more leniently,” while another in the same class said the discussions made the class “very difficult.” As rigor is a key principle of my teaching, I do not consider such comments to be indicative that the discussions did not play their role. I want my students to enjoy my classes, but I also recognize that students’ experiences with learning are like many people’s relationships with eating vegetables—it can be beneficial even if they do not necessarily like it.

Some students understand the difference between enjoying an aspect of a class and benefiting from it. “I hated the discussion boards,” a student enrolled in Immersive Crisis Communication wrote in the spring of 2022, “but I learned a lot from them!” In the same spirit, in the fall of 2021, a student enrolled in News Writing shared the following: “I hate having to do any discussion posts, but I will say that this class’ discussion assignments were better than any of my other classes,” while a classmate added, “Honestly, I found the discussion a little annoying at first. But once I got the hang of it, it [became] easier.”

Some students recognize the benefits of the discussions and enjoy this part of their learning experience. In the fall of 2021, another Opinion Writing student noted the conversations grow in meaningfulness when more students participate, an affirming reflection of co-creation. In the spring of 2022, a student enrolled in Public Affairs Reporting wrote the assigned readings were “enlightening and perspective broadening,” an indicator of self-discovery. A fall of 2021 Feature Writing student added: “I liked the discussion posts where we were able to answer each other’s questions and learn from one another,” a nod to social construction.

Many students who had their first experiences with online learning in 2020, the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic, seemed particularly appreciative of Pioneer Method discussions. In the spring of that year, a News Writing student shared that “I really liked the feedback from the professor and group discussions where students could collaborate,” and another added that “the discussions helped the online course to feel like normal classes. I enjoyed getting to know and communicate with other students this way.” In the fall of that year, there were more positive comments. “I felt that the discussions were an interesting part of the class and gave us students a good opportunity to discuss important matters and learn from each other,” a student enrolled in News Writing shared. “The online discussions were actually helpful and my classmates weren’t just ‘BSing’ their way through—I learned a ton from them,” a Feature Writing student added.

The students in spring 2021’s Podcasting class were a particularly enthusiastic lot. “I also loved the discussions and thought the prompts were engaging and the responses were genuine and natural,” one wrote. “I loved the weekly podcast discussions and the simplicity of the course. I never felt like I was doing busy work,” another added. “I really enjoyed the Pioneer Method of Discussion in our weekly class discussions. They really helped me understand different—sometimes opposing—world views,” a third noted. “I liked the ability to collaborate with other students both in the project and through discussion questions,” a fourth wrote.

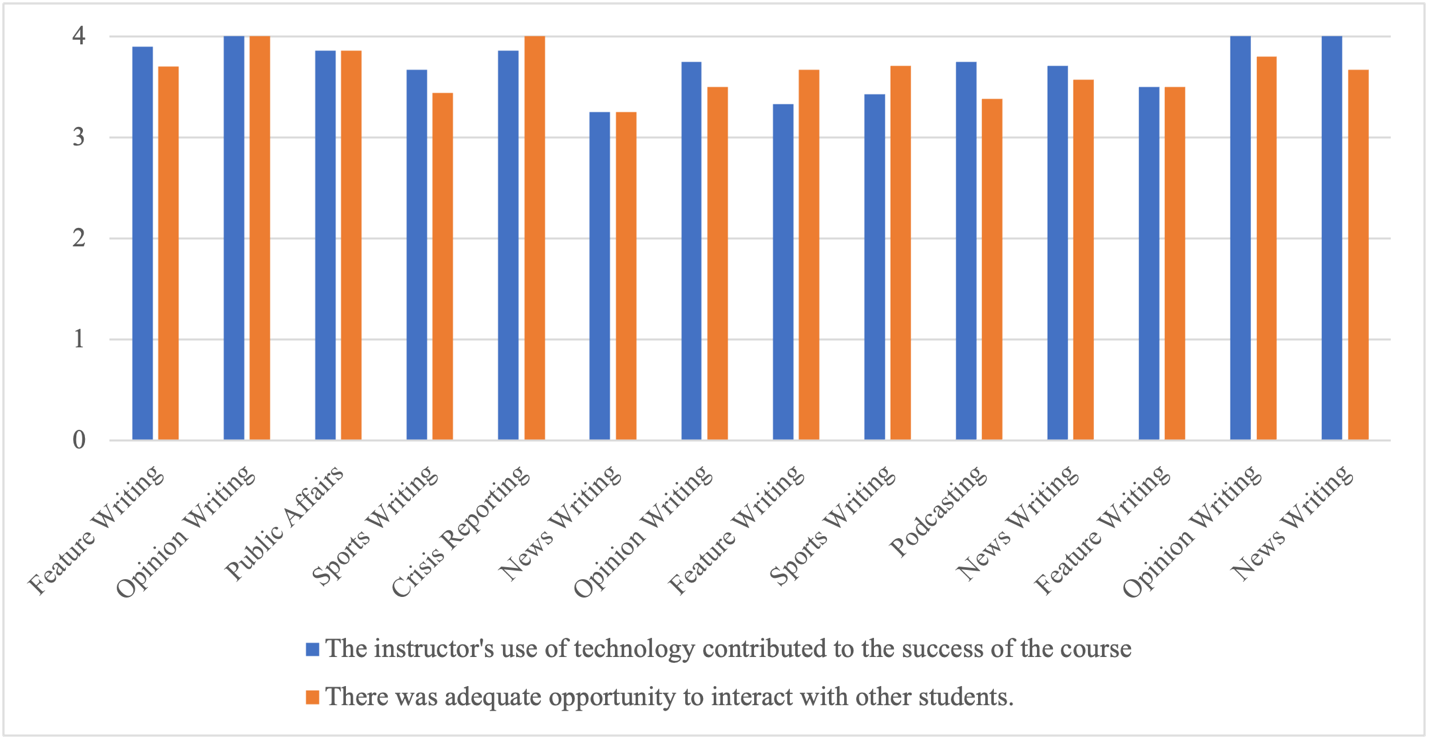

Quantitatively, there are two student-scored statements in the IDEA surveys that seem most relevant:

• The instructor’s use of technology contributed to the success of the course.

• There was adequate opportunity to interact with other students.

Students are asked to score these questions on a four-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Agree; 4 = Strongly Agree). For both assessment points, students have indicated strong agreement. Across 14 classes for which enough students participated in the course evaluations to merit qualitative summation, the average score for “The instructor’s use of technology contributed to the success of the course” was 3.72, and the average score for “There was adequate opportunity to interact with other students” was 3.65. While “instructor’s use of technology” may be inclusive of myriad parts of the course, it is important to note that there was no other group work or student-to-student interactions in these online classes, so “opportunity to interact with other students” could only refer to the discussions.

Figure 8.2

Fourteen Online Classes Using the Pioneer Method and Rigorous Scaffolding

Conclusion

“I’m not sure there is anything I dislike more than online discussion boards,” a teaching colleague recently confided in me.

“I’m not sure there’s anything I like more,” I told her. “May I tell you why?”

My colleague graciously accepted, and I told her much of what I have written here. True discussion—that which is student-dominated, interactive, contemplative, evidence-based, and promotive of voice, co-creation, social construction, and self-discovery—is not easy to achieve in any educational space. But I believe it is possible, and I commonly see it as an outcome of the Pioneer Method and the scaffolding that supports it.

Asynchronous discussion boards are now ubiquitous in online and hybrid classes—and common as a supplemental learning space for even primarily in-person classes—and yet few rigorous studies have been focused on identifying instructional improvements (de Lima et al., 2019). As a result, students and instructors alike still commonly express frustration with this part of the contemporary learning experience. So, into this relative void, I humbly offer the Pioneer Method and my experiences with it. It has served me and my students well, promoting habits such as listening with understanding and empathy, questioning and posing problems, thinking and communicating with clarity and precision, striving for accuracy, and thinking interdependently. I hope it will do all these things for your students, too.

References

Alvermann D. A., Dillon D. R., & O’Brien D. G. (1987). Using discussion to promote reading comprehension. International Reading Association.

Blaine, A. (2014). Creating safety by modeling vulnerability. Learning for Justice. https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/create-safety-by-modeling-vulnerability

Burgstahler, S., & Russo-Gleicher, R. J. (2015). Applying universal design to address the needs of postsecondary students on the autism spectrum. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28(2), 199–212.

Casey, L. J., Cogmon, J. D., LaPlante, M., & Sharpe, K. (2010). In the online learning revolution: A call to community [Group research report in fulfillment of the requirements of EDUI 6707]. California State University East Bay.

Covelli, B. (2017). Online discussion boards: The practice of building community for adult learners. Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 65(2), 139–145.

Daniels, D. E., Panico, J., & Sudholt, J. (2011). Perceptions of university instructors toward students who stutter: A quantitative and qualitative approach. Journal of Communication Disorders, 44(6), 631–639.

de Bont, A. P. (2018). Online persuasive learning: A study into the effectiveness of social-proof based online persuasion in a MOOC course [Master’s thesis, Leiden University]. Leiden.

de Lima, D., Gerosa, M., Conte, T., & de M. Netto, J. F. (2019). What to expect, and how to improve online discussion forums: The instructors’ perspective. Journal of Internet Services and Applications, 10(1), 22.

Edelson, D. C., Pea, R. D., & Gomez, L. (1995). Constructivism in the collaboratory. In Constructivist learning environments: Case studies in instructional design. Educational Technology Publications.

Gilbert, P. K., & Dabbagh, N. (2004). How to structure online discussions for meaningful discourse: A case study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 36(1), 5–18.

Guzzetti, B. J., Snyder, T. E., Glass, G. V., & Gamas, W. S. (1993). Promoting conceptual change in science: A comparative meta-analysis of instructional interventions from reading education and science education. Reading Research Quarterly, 28(2), 116–159.

Hall, R. M., & Sandler, B. R. (1982). The classroom climate: A chilly one for women? [Project on the status and education of women, Association of American Colleges]. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED215628.

Howard, J. R., Short, L. B., & Clark, S. M. (1996). Students’ participation in the mixed-age college classroom. Teaching Sociology, 24(1), 8–24.

Howard, J. R., Zoeller, A., & Pratt, Y. (2006). Students’ race and participation in sociology classroom discussion: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6(1), 14–38.

Kallick, B., & Zmuda, A. (2017). Students at the center: Personalized learning with Habits of Mind. ASCD.

Liu, J. (2021). Digital object identifier (DOI) under the context of research data librarianship. Journal of eScience Librarianship, 10(2), 4.

Oros, A. (2007). Let’s debate: Active learning encourages student participation and critical thinking. The Journal of Political Science Education, 3(1), 293–311.

Warschauer, M., & Matuchniak, T. (2010). New technology and digital worlds: Analyzing evidence of equity in access, use, and outcomes. Review of Research in Education, 34(1), 179–225.

Zakrajsek, T. (2017). Students who don’t participate in class discussions: They are not all introverts. The Scholarly Teacher. https://www.scholarlyteacher.com/post/students-who-dont-participate-in-class-discussions