12 Weaving Purposeful Worlds of Discovery: Merging CliftonStrengths® with Habits of Mind for Low-Income, First-Generation Students

Kimberly Hiatt; Kelsey Bushman; Heather Lyman; and Sarah Gosney

Utah State University (USU) Blanding is a non-tribal institution with close to 70% of its student population originating from the Navajo Nation, Dinétah. Located 388 miles southeast of the main campus in Logan, Utah, USU Blanding serves a population of students living in geographically remote areas, including the largest Native American–populated region in the United States. This vast territory—encompassing some 13,300 square miles, which exceeds the combined area of Connecticut, Delaware, New Jersey, and Rhode Island—is classified as “frontier.” With a population density of 2.0 persons per square mile and a poverty rate of 33% (as compared to the Utah average of 8.9%; Utah Department of Workforce Services, 2022), students at the elementary and secondary levels across this region face chronic food insecurity, limited access to transportation, early responsibility for sibling childcare, and limited (or no) access to Internet and running water. When basic needs cannot be met, the difficult yet rewarding work of deep learning is often put on the back burner (McGuire, 2018, p. 6). Add to this a higher-than-average teacher turnover rate, combined with regional school districts’ inclination to advance high school seniors who have for various reasons been underserved since elementary school, and you have future college students unprepared for the academic rigor of a university experience.

Unlike the Logan campus, which requires a certain GPA and index score for admittance, USU Blanding uses open enrollment, meaning that any student with a high school diploma or GED is admitted. That leaves student support groups that serve first-generation, income-eligible students (95% of whom are Navajo or Diné) like TRIO Student Support Services (SSS) with a critical and expedient task: to help the high number of underprepared students make up lost ground before either their financial aid or motivation runs out. It is a tall order—and not because these students are not capable, because they are. What is key is providing these students with useful tools in a familiar and timely manner before their financial resources and desire evaporate.

For these reasons, when applying for the latest TRIO SSS award, a federal educational opportunity outreach program designed to motivate and support college students from disadvantaged backgrounds, the USU Blanding TRIO SSS team chose to create new project services. We wanted to allow students to integrate their natural personality characteristics—or CliftonStrengths (CS)—together with Habits of Mind. This approach, we reasoned, would create a discovery framework upon which our students could achieve wellbeing in higher education.

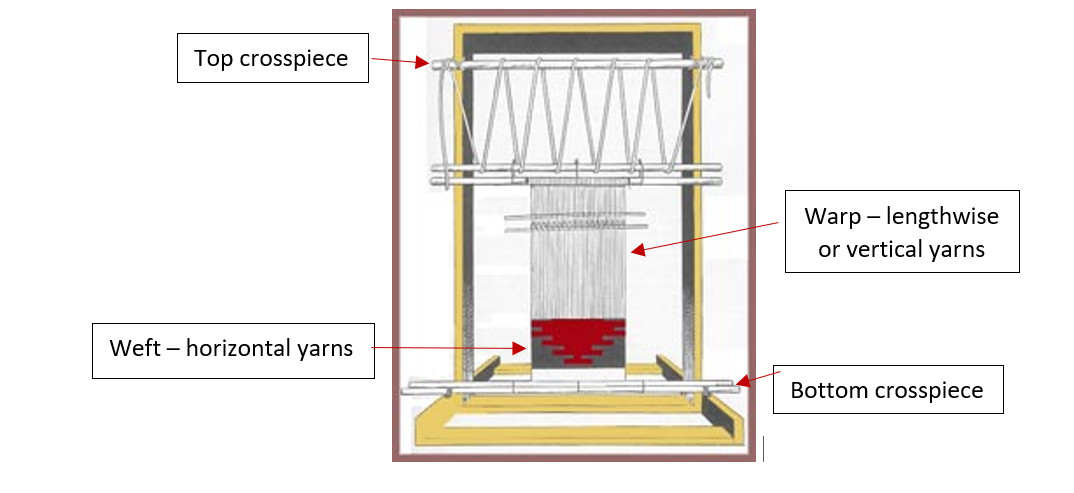

Offering our underprepared students the space and time to “weave” a world of discovery using the tools of CS and Habits of Mind is analogous to a structure with which these students are already familiar: the taut longitudinal and interwoven vertical yarns found on the two-bar loom Navajo weavers have used for the past two centuries to create vivid, artistic, durable blankets. Navajo artisans are known worldwide for the beauty, intricacy, and quality of their wool blankets and rugs woven on the traditional, freestanding, upright, rudimentary but well-suited Navajo looms (see Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1

Navajo Rug Weaving Loom (2016)

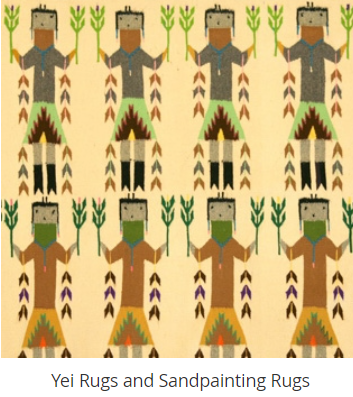

Figure 12.2

Klagetoh (left) and Yei (right) Patterned Navajo Blankets (Sublette, 2022)

This exquisite and enduring storytelling art includes warp (horizontal) and weft (vertical) yarns of churro sheep wool, raised, sheared, carded, dyed and spun into natural-colored fibers. It is a time-intensive artform that a 1973 Diné Community College study estimated takes an average of 345 hours: 45 hours to shear the sheep, 24 hours to spin the wool, 60 hours to prep and dye the wool, and 215 hours to weave (Jakobsen, 2017). Our students hear stories from their K’é (Navajo system of kinship) that after they emerged from the Fourth, Glittering World, a Holy Person named Changing Woman sought out the weaving art from Spider Woman. Spider Woman gifted Changing Woman with weaving knowledge, though only after Changing Woman promised to teach other Navajo women how to weave (Roessel, 1995, p. 21–22). Navajo weavers know the warp (or lengthwise) lashings must be stretched on the loom under great tension to facilitate the weft yarns that are woven up and over the stronger yarns to form intricate, colorful textile stories.

Our mission is to guide our students to identify the taut, warp lengthwise lashings on their own looms—their natural strengths or unique talents innate or learned through refining life experience that, when named, claimed, and aimed, will reveal natural tendencies that create the necessary and intelligent weft behaviors on their looms of life. Though it takes time and repeated practice, like the long hours devoted to creating a stunning Navajo blanket, we believe that when a student tightly knits these two valuable intersecting pieces into their character, they will preserve their individual and collective identity, all while building the stability to accept necessary change for responsible growth and familial economic development.

CliftonStrengths: Revealing Our Students’ Natural, Intrinsic Talent

The CS psychometric instrument is a reliable, enduring assessment taken by well over 21 million people worldwide in 25 different languages (Asplund, 2019). Offering it to our students and certifying three of our five staff as CS coaches has expanded the engagement of our project. Since administering this positive assessment focused on identifying and developing students’ strengths (or talent themes) rather than addressing their deficits, we have noticed that our students are generally more satisfied when using their natural strengths in both their academic and social lives. Through strengths-based activities, they come to understand that they, like a Navajo blanket, have progressed from the ground up. Because they get an opportunity to engage their natural talent themes in all areas of academic life, they perform better in school.

Providing the CS assessment to all our participants allows students to learn their top five themes of talent. These are the areas where they have the most potential to shine. Students receive a detailed report about each of their themes of talent. Additionally, a coaching session and at least one lesson during each first- and second-year experience Habits of Mind course is devoted to understanding and fostering these strengths in a way that helps students capitalize on their own potential. Most importantly, our team works the language of CliftonStrengths into every aspect of the project. Each Habits of Mind lesson, advising session, learning session, and everyday interaction with students is framed with their talent themes in mind. As a result, many students ask to learn more about their themes of talent outside of the classroom. When discussing students’ talent themes, TRIO staff focus on the whole student, including how they are thriving, surviving, or struggling with their well-being in the following areas: academically, socially, financially, physically, and communally.

Habits of Mind

CS perfectly complements the interlacing of Habits of Mind applicability. Discovering ourselves is the human journey. Thus, when students come to know their talent themes and how they dynamically wrap with one another, they can more fully awaken their “Habits of Mind to drive, motivate, activate and direct their intellectual capacities” (as quoted by Art Costa in Bena, 2017). Yet it is critical to realize that for Navajo students, it is all about family and traditions, whereas in Western culture, it is mostly about the individual. According to Guillory and Wolverton (2008), institutions like USU Blanding, which serve Native American students, “cannot continue to operate using traditional approaches to student retention, if they want to truly serve and help our country’s Indigenous peoples” (p. 84). Heavy Runner and DeCelles go so far to say that “institutions fail to recognize the disconnect between the institutional values and [Indigenous] student/family values; hence the real reasons for high attrition rates among disadvantaged students are never addressed” (2002, p. 8). Connecting to students’ home communities, traditions, and individual strengths is imperative.

Weaving in the vertical, weft Habits of Mind yarns, though subject to less strain than the warp yarns, requires the constant carry-over and carry-under activity through these lengthwise fibers. Like the rich Navajo tradition of weaving weft yarns, this “duration of long, slow building of millimeter-by-millimeter work” (Biggers, 2021) resembles the Habits of Mind learning that initially arrives at our campus in the form of students’ discourse mismatch. While not all students come to institutions of higher learning with the language of Habits of Mind, all students arrive with a rich and unique culture. Tying our students to their sense of self and membership in a group, where the student grew up, the place they learned to be, and who they identify themselves as being, as well as to feelings of belonging helps them succeed when their primary discourse does not match the institutional discourse.

While Habits of Mind seem like clear attributes students should be taught to behave intelligently, they are attributes described in language that makes sense in the Western world, though not necessarily in the primary discourse of Native American students. As Paulson infers, “when a student’s primary discourse suddenly becomes ‘wrong’ in the college’s official, secondary discourse community,” there is a discourse mismatch in education (2012, p. 7–8). Such a discontinuity in the weaving can easily result in student frustration and a lack of persistence. It is critical that our students are allowed to tie their natural strengths and traditions to the secondary discourse of Habits of Mind so they can learn the expectations and behaviors of academic and lifetime success. Figure 12.3 shows how the 34 CS combine with the 16 Habits of Mind to benefit our specific student population. After administering almost 400 CS assessments to TRIO SSS students, 95% of whom are Navajo students, *restorative (CS) is the highest recurring talent theme.

Figure 12.3

Weaving CliftonStrengths and Habits of Mind

|

Habits of Mind |

Habits of Mind Explanation |

Clifton Strengths Talent Theme Dynamics That Could be Applied to Habits of Mind |

CliftonStrengths/Habits of Mind Weaving Benefit for Students |

|

1. Persisting: Stick to it! |

Persevering with a task through to completion, remaining focused. Searching for ways to reach your goal when stuck. Not giving up. |

Focus Discipline Competition Consistency Activator |

We look for ways to help our students reach their goals when they are stuck. We do not let them give up. We show them how to persevere just like the Diné persevered through harsh environments, assimilation, the “Long Walk” farming, weaving, arts, and crafts and education. |

|

2. Managing impulsivity: Take your time! |

Thinking before acting; remaining calm, thoughtful, and deliberative. |

Deliberative Command Responsibility |

“I can’t. I’m scared.” These are common phrases we hear from our students. Meditation and mindfulness practices help our students to think positively about their talent themes and remain calm, thoughtful, and deliberate before acting. Hózhó is order, beauty, balance, and harmony in the Navajo language. Practicing mindfulness is a tool we use in our Habits of Mind classes to reconnect students with this beauty way. |

|

3. Listening with understanding and empathy: Understanding others! |

Devoting mental energy to another person’s thoughts and ideas. Trying to perceive another’s point of view and emotions. |

Empathy Includer Relator |

Our team recognizes that our students see outside themselves and beyond their situation. It is a group dynamic with which our students excel. This can translate into great marketable job skills. It is no surprise since family and community are vital to our Navajo students. |

|

4. Thinking flexibly: Look at it another way! |

Being able to change perspectives; generating alternatives; considering options. |

Adaptability Arranger Strategic Futuristic Restorative* |

We help our students change their perspectives (often negative from various home environments and experiences) through their restorative strengths in considering other options to generate alternatives (e.g., medical assisting versus nursing). Students have seen grandfathers die in hospitals from respiratory damage due to their years in uranium mines, or grandmothers in kidney failure from poorly controlled diabetes. Their experiences with hospitals create a desire to “be a nurse.” Yet students often find the academic rigors into that program to be too challenging. Showing them other options like the Medical Lab or Surgical Technician AAS or the Medical Assistant or Pharmacy Technician Certificate of Completion are pleasing alternatives. |

|

5. Thinking about your thinking: Metacognition |

Being aware of your own thoughts, strategies, feelings, and actions and their effects on others |

Intellection Strategic Learner |

We share the learning cycle adapted from Dr. Saundra McGuire (2018) with our students so they will be aware of their own thoughts, strategies, feelings, and actions and their effects on them and others. Circular thinking that includes staying with others or tasks until the interaction is complete is part of Navajo life. |

|

6. Striving for accuracy: Check it again! |

Doing your best. Setting high standards. Fact checking and finding ways to improve. |

Achiever Maximizer |

The Navajo Protection Way Blessing includes the instruction Doo hoł hóyée’ da (never be lazy). This is a skill we teach our students in their college writing: set high standards when using and citing sources to avoid plagiarism and check their sources for credibility. |

|

7. Questioning and posing problems: How do you know? |

Having a questioning attitude; knowing what data are needed and developing questioning strategies to produce those data. Finding problems to solve. |

Restorative* Analytical |

We encourage students to become lifelong learners by engaging with material in more depth, which helps them retain it for a longer period of time. We ask them to spend more time wallowing in the complexity of problems so they can see it from different angles. |

|

8. Applying past knowledge to new situations: Use what you learn! |

Accessing prior knowledge; transferring knowledge beyond the situation in which it was learned. |

Context Learner Restorative* Input Futuristic |

Our students have a rich cultural history to pull from when accessing prior knowledge in all academic areas (science, history, fiction, human and family development, etc.). Conveying this message to students confirms to them that they are intelligent and capable individuals and can gain the knowledge necessary to be successful in all academic settings. |

|

9. Thinking and communicating with clarity and precision: Be clear! |

Striving for accurate communication in both written and oral form; avoiding overgeneralizations, distortions, deletions, and exaggerations. |

Communication Consistency Focus Maximizer Harmony |

As English language learners (ELLs), many of our students experience achievement gaps, which makes communicating with clarity and precision challenging. However, when students see the importance of communicating precisely with their instructors, they often find that they get answers, direction, and feedback which are clear and precise. Doing so increases understanding on both sides of the communication. |

|

10. Gathering data through all senses: Use your natural pathways! |

Paying attention to the world around you. Gathering data through all the senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. |

Input Analytical Connectedness Harmony |

Helping students find their natural learning tendencies will strengthen as well as encourage them to use other pathways to learn. As a TRIO SSS team, we are constantly discovering the best ways our students learn. Just as each weaver’s design is unique to them, so are each of our students’ ways of learning. |

|

11. Creating, imagining, and innovating: Try a different way! |

Generating new and novel ideas, fluency, originality |

Ideation Strategic Analytical Activator |

We have seen more creativity in our Navajo students than in any other group of students. They naturally unearth original ideas and thoughts of their own, which empowers them to continue to learn and grow. Pointing out this general, natural tendency can encourage originality and fluency. |

|

12. Responding with wonderment and awe: Having fun figuring it out! |

Finding the world awesome, mysterious, and being intrigued with phenomena and beauty. |

Belief Connectedness Learner |

We help our students feel a sense of pride for the accomplishments they make in academic discourse, which they may not be able to acknowledge in their primary discourse. Two years with us in the TRIO SSS project becomes a memorable woven tapestry of progress, celebrated by their TRIO SSS shimá yázhí (aunties). |

|

13. Taking responsible risks: Venture out! |

Being adventuresome; living on the edge of one’s competence. Try new things constantly. |

Maximizer Self-Assurance Significance ResponsibilityActivator |

We have found that our students feel less limited when they try new things and venture beyond what they know. Although creating new designs can seem scary to them at first, through practice and encouragement, this limitlessness can translate into an insatiable appetite for leaning into the unknown. |

|

14. Finding humor: Laugh a little! |

Finding the whimsical, incongruous, and unexpected. Being able to laugh at oneself. |

Woo Positivity Adaptability Belief Communication |

Our team has a collective 60 years of teaching Navajo students, and one thing that stands out is that Navajo students love to tease and laugh. As nationally known Native American comedian, humorist, and speaker Mylo Redwater Smith has said, “Indian humor is much more than a social lubricant, it’s a tool, an attitude, a mentality” (Lindquist, 2016). We learn better when we are in a good mood, and learning to laugh at ourselves and the unexpected helps us maintain that lightheartedness, which, in turn, may lead to a greater openness about what we are learning. |

|

15. Thinking interdependently: Work together! |

Working with and learning from others in reciprocal situations. Teamwork. |

Woo Ideation Includer Futuristic Individualization |

We learned through the pandemic that our students missed connecting with others. This process of involving others in learning can be enlightening as ideas are shared and may even help to shift current mindsets or clear certain obstacles in our thinking. |

|

16. Remaining open to continuous learning: Learn from experience! |

Having humility and pride when admitting we do not know; resisting complacency. |

Learner Input Ideation Intellection |

We have learned that humility is part of the Navajo traditional education. One of the Blessing Way teachings is being humble: yiní dilyinee jiiná. We help our students remain open to continuous learning by teaching them about academic discourse, how to navigate the institution, and introducing them to new ways of learning that weave into mindfulness, a skill based in their cultural traditions. |

Note. The Institute for Habits of Mind (2022) and Gallup, Inc. (2019).

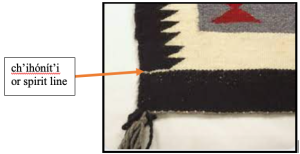

With a focus on student strengths, our team understands the importance of helping our students explore their blind spots—the overused or misapplied strengths that pose as weaknesses. These show up when we ignore instead of invest in our natural strengths. When constructing a Navajo blanket, weavers design a spirit line, ch’ihónít’i, or intentional opening “into a textile [as] a preventative measure that disentangles the artists from the finished product created to sell in the wider marketplace” (Yohe, 2012). Weavers believe that the spirit line opening they fabricate maintains their physical and mental health by providing them an exit or opening so they do not enclose their spirit or halt their learning in the rug (Rodee, 1987, p. 141). (See Figure 12.4 for a spirit pathway example.) In a similar manner, our students need to be aware of their weaknesses so they can create a ch’ihónít’i of escape for these blind spots. For example, a student with high talent themes of Input and Learner may tend to overshare what they have learned in their classes. If this student becomes aware that this behavior will not win them a steady lineup of study group partners in the future, they can work on that blind spot so that this weakness exits their metaphorical spirit pathway.

Figure 12.4

Spirit Pathway (Sinopoli, 2017)

Standing out is one blind spot we have seen emerge from the loom of our students’ Navajo culture. Asking for help is not something that most of our students will do comfortably or naturally. With a culture that does not encourage assertiveness, most of our students attempt to fly just under the radar, trying to not be noticed for anything they do (or do not) accomplish. They are not comfortable asking for help or being praised. Sometimes even something as simple as eye contact can be difficult for our students, especially for those who are traditional. Compounding this difference in culture with a new living situation in a border town with mostly white faculty and staff, the challenges of collegiate academic rigor, and a newly discovered independence, and a student may shut down. Managing so much at once is challenging for any young adult, but our students tend to fare worse than most. Some come out of their first semester, sometimes their first year, of college in tatters, either mentally or academically. Incorporating CliftonStrengths and Habits of Mind early and often in all that we do benefits our students with learned persistence, confidence, and success.

Creating an Environment for Engaged Weaving: Learning and Growing

During the Covid-19 pandemic, we learned that human contact and connection are essential. Our students verbalized that they missed the personalized connection of face-to-face classes and one-on-one advising sessions. With ways of belonging stripped from our shared cultures, we realized how much they were valued—“where their voice[s] can be heard, where they are invited to the table for problem solving and innovative thinking, where their differences are seen as strengths, and where there is a dedication to their overall well-being” (Costa et al., 2021). Thus, we created connections inside our Habits of Mind first- and second-year seminars and continued weaving those connections outside the classroom through Habits of Mind assignment-required advising appointments with our TRIO academic advisor and learning sessions with our TRIO learning specialist.

We found that culturally responsive teaching, including connections to home, traditions, and previous knowledge, encourage our students to thrive. Navajo weavers innately saw the importance of connections to home and traditions as they have been known to incorporate memorable and deliberate items into their designs “related to stories or the ceremonial procedures that grow out of them” (Willink & Zolbrod, 1996, p. 8–10). In fact, sometimes traditional knowledge in the form of a sliver of quill, a tiny piece of pollen, or a subtle color shift is woven into these rugs, not so unlike learning strategies that remind students of prior knowledge—keeping a story or knowledge alive for longer than needed to regurgitate for an exam.

In one Habits of Mind class, USU 1060: Reading for College Success, we help students become more mindful about where and how they learn in their classes. The class fashions three reading strategy categories into academic text comprehension: pre-reading, during reading, and post-reading. One specific reading strategy is the use of mnemonic devices: memory techniques that methodically change difficult-to-remember details into more easily remembered details. Mnemonic devices are commonly used in the elementary and secondary grades. For example, ROY G BIV for the colors of the rainbow and PEMDAS for the order of operations in math. Creating an original mnemonic device that will work for you is another beast entirely, which is exactly what students are asked to do in USU 1060.

One student was cruising along through each reading strategy until we got to mnemonic devices. The assignment became for her an insurmountable challenge, particularly the aspect of creating a new device. She mentioned in class that she was having trouble with that assignment and asked the instructor for help.

After determining that it was the innovation factor of the assignment that was the challenge, the instructor asked this student to identify something she was either having a hard time remembering or could not master. The student identified an animal science class as difficult because of an upcoming test on the meticulous details about each type of cattle. She had three pages of carefully scrawled notes with all the information she had to memorize. With the talent themes of deliberative and maximizer in her top five CliftonStrengths, it was no surprise that this student took serious care to be organized and sought to transform a strong learning strategy into something superb. Still, these notes just were not sticking with her. She was persistent because she had to learn the information, but the skills that had always worked for her in the past were not helping her in this situation.

Beginning the process of creating a mnemonic device, the instructor asked her to identify the categories that each type of cattle had in common (for example, the class of cattle, where they originated, what type of beef each produced, and the personality type of each cow). After determining that these categories were the chunks of her mnemonic device, the student slowly began to add in all the other information where it fit. With the help of her instructor, the student practiced alliteration, identified compound words, referred to people she knew (a boy named Scot was popular in her high school, as are Scotland Angus cattle) and even language differences to fill in the rest of the information about beef. Those three pages turned into one mnemonic device. Some of the connections were stretching it, but the sillier the connection, the easier the student could remember it.

Like a braiding plait, the blend of this student’s deliberative and maximizer talent themes allowed her to proceed cautiously and thoroughly when she could not compromise quality with specific Habits of Mind, like persisting; thinking flexibly; posing questions and problems; creating, imagining, and innovating; and taking responsible risks. This created a credible learning strategy in a mnemonic device that worked for her. And the bonus is that after a whole year, the student still remembers this information!

Choosing an Individual Design: Personalizing Student Learning

Intertwining metacognition with students’ CliftonStrengths empowers them toward ádaa’ áhozhniidzii’ (becoming self-aware) of the specific learning strategies that work best for them—a type of self-care in the often-foreign world of higher education for Navajo students. While one student may be exceptionally talented at organizing and determining how all the pieces and resources can be assembled for maximum productivity using their arranger talent theme, another student may intertwine their includer and responsibility talent themes to create a dynamic double weave where they stand out at serving the marginalized (Gallup, 2019). On the other hand, a student with achiever and individualization high in their top five talent themes may be more effective at completing a task when they can work in a manner that fits who they are as a person (Gallup, 2019).

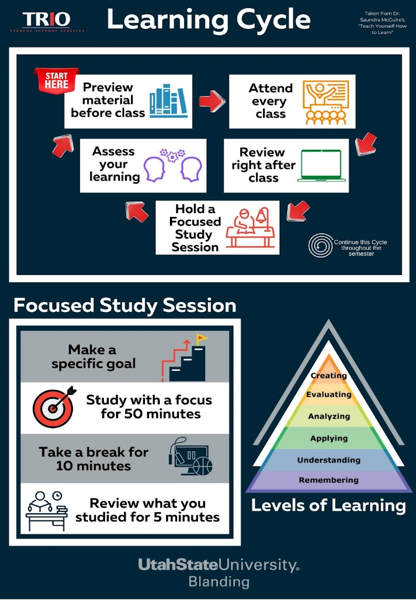

Our efforts to meld Habits of Mind with CliftonStrengths has revealed some important findings. We have learned, for example, that the fifth Habit of Mind, metacognition, is an effective way for students to be self-reflective, particularly about their learning. Furthermore, many Habits of Mind come into play with this particular focus: persisting, managing impulsivity, striving for accuracy, questioning, thinking independently and remaining open to continuous learning. Our application of metacognition stems from our application of Saundra McGuire’s (2018) “Teach Yourself How to Learn.” In this piece, McGuire introduces a study cycle attentive to specific components of the learning process.

To break down this process for students, we ask them what types of learning were required of them when they were in high school. We then ask them to compare that to the learning required of them at the college level. Through this exercise, students offer concrete examples that show the significant difference between what was required from them in high school and now in college.

In another Habits of Mind course, USU 1040: Learning for Student Success, we take the time to process and practice (and practice some more) the important steps in the learning cycle. This careful approach allows our students to repeat the following important pattern for their academic courses: a) preview material before class; b) attend every class; c) review right after class; d) hold a focused study session between each student and TRIO SSS staff to determine the amount of time necessary to study and the amount of time necessary for brain “breaks”; e) assess their learning; and f) repeat what worked and adjust what needs fine-tuning (see Figure 12.5).

Figure 12.5

USU Blanding TRIO SSS poster (2021)

Weaving Strengths and Habits of Mind Into Academic Advising

Navajo tradition relates that Changing Woman promised to share her knowledge of weaving with Navajo women, so the art remains alive in Diné culture with that continued promise kept by the few master weavers still crafting stunning blankets. First-generation students in our project do not get that same promise with higher education, thus their first-gen status. For this reason, academic advising/transfer counseling is a mandated service in our federal project, and we, like Changing Woman, take this promise to share our knowledge as well as advice, assistance in postsecondary course selection, and information on the full range of student financial aid programs, transfer opportunities, and student support tools very seriously.

In our advising practices, we interlace a combination of CliftonStrengths-based advising, appreciative advising, and Habits of Mind. With financial wellness on her mind, one student came to visit our academic advisor about the grant aid our project offers. Though they began by talking about the requirements and deadlines for TRIO SSS grant aid, soon the conversation turned to some of the student’s concerns for the current semester, including effective time management. For Navajo students, cultural time perception has a direct correlation to academic success. “Navajo time” is a term used in an “off-the-cuff way to explain why events that [are] hosted, planned, or attended by Navajo people always seem to start late and go long” (Charles, 2011). Timeliness in Navajo culture does not communicate value as it does in Western customs.

As a full-time and working student, this student’s time was limited. She expressed a desire to “figure out” her schedule so that she could be better prepared and organized. We implemented two time-management resources: a weekly planning schedule to allow the student to input all her classes, work times, and activities to create a snapshot view of her week and then schedule transitory activities and events into her schedule, and a semester-planning schedule that the student and advisor filled in with semester-long due dates. They ended the session with a conversation about filling in the assignments, tests, and other important dates for the entire semester to help plan out her time and prioritize tasks during the semester. Though this student came in seeking an answer to a financial wellness question, she was able to create a critical discussion of several Habits of Mind (e.g., thinking interdependently, persisting) she can now practice with specific advising tools to become more successful in her student role. This kind of one-stop shop for answers, encouragement, CliftonStrengths coaching, and lessons on Habits of Mind take place daily with our students and the TRIO SSS staff.

Since lashing CliftonStrengths with Habit of Mind as the framework of our project, we have provided students with specific and transferable opportunities to see themselves as the powerful, capable individuals their Creation Stories dictate they are. Simply put, this well-built structure provides textured, intelligent behavior opportunities that help students sustain a stable framework necessary for change, responsible growth, and familial economic development, all of which are essential on the Navajo Nation today and in the future.

The similarities to the Navajo weaver’s loom, with its bottom cross piece representing Mother Earth securely holding the stretched, vertically rising yarns toward the top of the loom’s cross piece representing Father Sky, metaphorically illustrate how our students learn to leverage their own natural talent themes standing on Mother Earth while practicing the continuous weaving art of specific Habits of Mind. The more practice and experience our students acquire, the taller they reach toward Father Sky. Weaving Navajo traditions with their CliftonStrengths and Habits of Mind has the potential to create new worlds of proactive and prepared discovery for students as they set and reach goals that bring productive change to them and, if they master the secondary discourse of the institution and their people are willing to receive their translated version, to their home communities.

References

Asplund, J. (2019). Stability of CliftonStrengths® results over time. Gallup, Inc.

Campbell, S., Redman, K., & Kent, N. (2016, February 29). Navajo rug weaving loom. Taos Trading Post. https://taostradingpost.com/navajo-rug-weaving-loom/

Charles, M. (2011, August 4–7). Time perception among Navajo American Indians and its relation to academic success [Paper presentation]. 119th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C.

Costa, A. L., Kallick, B., & Zmuda, A. (2021). Building a culture of efficacy with habits of mind. ASCD, 79(3). https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/building-a-culture-of-efficacy-with-habits-of-mind

Gallup, Inc. (2019). What are the 34 cliftonstrengths themes?

https://www.gallup.com/cliftonstrengths/en/253715/34-cliftonstrengths-themes.aspx

Heavy Runner, L., & DeCelles, R. (2002). Family education model: Meeting the student retention challenge. Journal of American Indian Education, 41(2), 29–37.

The Institute for Habits of Mind. (2022). https://www.habitsofmindinstitute.org/

Jakobsen, M. (2017). The full history of Navajo blankets and rugs. Heddels. https://www.heddels.com/2017/04/navajo-blankets-and-rugs/

Kallick, B. & Zmuda, A. (2017). Students at the center: personalized learning with habits of mind. ASCD.

Lindquist, C. (2016). Very good medicine: Indigenous humor and laughter. Tribal College Journal of American Indian Higher Education, 27(4).

McGuire, S. Y. (2018). Teach yourself how to learn. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Paulson, E. J. (2012). A discourse mismatch theory of college learning. In K. Age & R. Hodges (Eds.), Handbook for training peer tutors and mentors (pp. 7–10). Essay, Cengage Learning.

Pickenpaugh, E. N., Yoast, S. R., Baker, A. & Vaughan, A. L. (2022). The role of first-year seminars and first-year college achievement for undeclared students. Higher Education, 83, 1063–1077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00729-0

Rodee, M. (1987). Weaving of the Southwest. Schiffer Publishing, Ltd.

Roessel, M. (1995). Songs of the loom: A Navajo girl learns to weave. Lerner Publications Company.

Sinopoli, C. M. (2017). Less than perfect: Weaving a spirit pathway. University of Michigan. https://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/less-than-perfect/about.php

Sublette, M. (2022). Navajo rugs and blankets [Review of Navajo Rugs and Blankets]. Medicine Man Gallery. https://www.medicinemangallery.com/native-american-art/navajo-rugs-navajo-blankets-for-sale

Utah Department of Workforce Services. (2022). Utah’s 11th annual report: Intergenerational poverty. Intergenerational Welfare Reform Commission. https://jobs.utah.gov/edo/intergenerational/igp22.pdf

Willink, R. S. & Zolbrod, P. G. (1996). Weaving a world: Textiles and the Navajo way of seeing. Museum of New Mexico Press.

Yohe, J. A. (2012). Situated flow: A few thoughts on reweaving meaning in the Navajo spirit pathway. Museum Anthropology Review, 6(1).