13 Habits of Mind Courses for College Success: Empowering Students to Plan and Read

Melanie Chambers and Sharon Lyman

Ana takes a deep breath as her professor hands back her midterm. To her chagrin, she sees a red F at the top of the page. As she wonders where things went awry, her mind replays the events leading up to her arrival at the testing center where she took the exam. Poor time management coupled with little to no interest in the assigned readings seemed to be the compounding culprits of her failed exam. Now, in place of the A she had envisioned herself earning, an unsettling feeling sets in. Ana wonders whether she can still pass the class.

University students with experiences like Ana’s can seek academic resources to help them succeed. Most students are hungry to find ways to improve their study habits, but few know where to look when failure begins to feel imminent. Classes that offer support have existed at Utah State University (USU) for decades. But it was not until 2020 that these study strategy classes were rebranded as “Habits of Mind” courses.

Habits of Mind classes build on what students learn at USU in Connections, their first-year orientation class. Habits of Mind courses are designed for students to take at the beginning of their college experience, though all students can benefit through the deliberate development of Habits of Mind. USU decided to offer these courses as one-credit, 7-week classes with specific focus areas. The original focus areas included planning; resilience; learning; reading, and success in STEM. By making each course 7 weeks long, these classes can be offered in the first and second part of the semester. Increased course offerings allow more students to take Habits of Mind courses.

USU’s land-grant mission seeks to make higher education accessible to everyone throughout the state of Utah. As such, we offer Habits of Mind courses in a variety of modalities, including in-person, online, and web broadcast (or “Connect”). These modalities increase student access and accommodate the needs of individual learners. USU’s Habits of Mind courses equip students with the behaviors and practices they need to succeed in college and beyond.

USU has adjusted some of its add/drop policies to help students gain these study skills. Students like Ana, for instance, can drop a full-semester, three-credit course and replace it with three, one-credit Habits of Mind classes. Habits of Mind courses provide students with a space to practice their skills and a safe community to build accountability. Students then become better prepared to revisit the course that they dropped. Since there is a direct correlation between self-efficacy and academic performance, students with high self-efficacy experience greater academic success (Wernersbach, 2011).

This chapter is co-authored by two USU learning specialists. We share our anecdotal experiences from teaching planning and reading courses. We have chosen to explore the following three Habits of Mind from the Habits of Mind Institute: managing impulsivity, persisting, and thinking flexibly. These Habits of Mind can inspire and help instructors know how to support their students. In the following, we first address how we build these Habits of Mind in USU 1020: Planning for College Success. We then move on to exploring how the Habits of Mind of managing impulsivity, persisting, and thinking flexibility have been incorporated into USU: 1060: Reading for College Success.

USU 1020: Habits of Mind: Planning for College Success

Background

USU 1020: Planning for College Success was the first course created in USU’s Habits of Mind series. In USU’s Academic Support Model (link), there is a tag line under time management that says, “Begin here.” Planning is the foundation of the academic support work we do because that is where problems first arise. “Evidence of students’ engagement in effective time management tends to be associated positively with indicators of more adaptive motivation and with increased use of other self-regulatory strategies” (Wolters & Brady, 2020). Academic issues can be prevented with awareness to scheduling limitations and approaching time with intention.

Students often arrive to college without the careful supervision of their parents or others who helped them through high school. For many students, their schedules are truly their own for the first time. This leads students to face down several challenges; many become unsure of how to approach these challenges. While students want to be the best version of themselves, we as university instructors must also be attuned to ensuring that students’ time-management plans are realistic.

Enrollment for our planning course fills fast. We believe this is because time management is an acceptable struggle that everyone faces. Students openly lament, commiserate, bond, and joke about their habits of procrastination and poor planning. They recognize that they have plenty of room for improvement. And they are eager to learn the many approaches that can be applied to improve their time management. The Habits of Mind that are cultivated from USU 1020 lead students to manage their impulses, develop persistence, and think flexibly.

Managing Impulsivity

Managing impulsivity means thinking before acting. When students can manage and control their impulses, they submit better work. They have time to engage in the creative process and explore connections between what they are learning in their courses. Anxiety impedes clear thinking, so when students delay starting an assignment until an hour before it is due, they rarely get as much out of the assignment as students who plan and choose to focus on the task for multiple days. The pressure to finish and submit the assignment on time when being completed in the final hour often leads to errors. It also reduces the quality of the work. In contrast, students who take time to prepare for, complete, and turn in their assignments experience greater confidence and higher retention of the material.

Students are also surrounded by distractions, inundated with devices that feed impulsivity. Laptops, cell phones, and watches all buzz to compete for attention. Textbooks, which are likely not as entertaining as the latest social media trend, patiently wait for the student to crack them open. Managing impulsivity when facing hours of reading, then, is something our students need to work on.

The most common obstacle that students report in USU 1020 is procrastination. We go over the reasons why, and how students procrastinate as well as what solutions have worked in the past. Some of our solutions include breaking up large projects into smaller tasks and using apps to help students engage in their schoolwork. Almost universally, students mention adjusting their phone settings or location for increased concentration. Students take time in class to reflect on the values that are important to them. After reflecting on their values, they use this information to prioritize their tasks by order of importance. The benefits of applying time-management skills contribute to college success and general well-being. These skills also apply to other life endeavors that extend beyond the college classroom.

The Five-Day Study Plan is an assignment in USU 1020 where students plan out a high-stakes academic task. The example below focuses on a test, but students can also plan out a paper or project. In the first column, students make five “appointments” and specify the days and times when they will study. If something comes up and they cannot make that day or time work, instead of skipping it, they reschedule. In the second column, students break down the content into smaller pieces so the temptation to cram diminishes. Focusing on this specific section helps overwhelming feelings dissipate. It also fosters a greater sense of concentration. In the third column, students use a variety of methods to study, giving them a greater chance of remembering the information in different formats (Brown et al., 2018). When it comes time for the test, they have several methods and options from which to pull information. The last column serves as a guide for what works, what needs adjusting, and what deserves additional focus. Students can report how well the appointment went, whether the concepts have been mastered, and how effective the study method was. This reflection exercise is integral in helping them become self-regulated learners (Nilson, 2013).

Figure 13.1

Five-Day Review Plan

|

Course: Test Date: |

|||

|

When – Date Time |

What – Chapter / Sections Test Topics |

How – Study Aids for the Topic |

Reflect |

|

Count back five days from test date |

List the chapters to be studied and the topics of the test |

List the study aids to be used in session – having variety will solidify the concepts. Review the active study strategy menu below |

How did the session go? What do you still want to review? |

|

Day 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Day 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Day 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Day 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Day 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. From Utah State University (n.d.-a).

Persisting

Getting stuck is frustrating. We have witnessed students give up for reasons like self-doubt, overwhelming life situations, or lack of purpose. While working with students, we have concluded that there is a story behind every F. University students face many barriers in their journey, and their response to such obstacles reveals their character and whether they have developed resilience. We have seen students who succumb to obstacles and others who overcome difficult challenges. The key is persisting. That is why we focus on this Habit of Mind in USU 1020.

Persisting is sticking with something until it is finished. Concentration is an important part of this Habit of Mind. Searching for a way to overcome obstacles can help planning be more effective and highlight the growth and progress made (Kallik & Costa, 2022). This Habit of Mind is a key part of college success, no matter what obstacle is in the way.

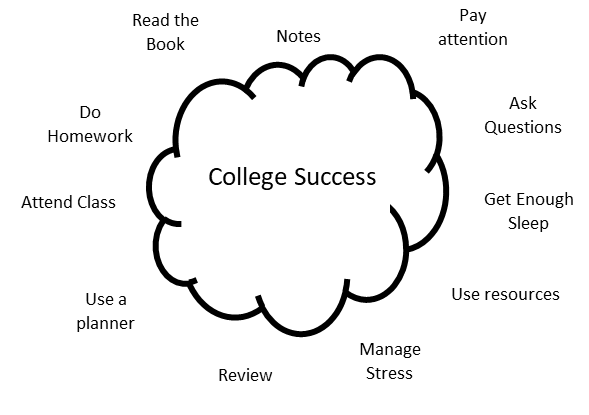

One approach we have in USU 1020 is breaking down big goals and aspirations into smaller steps. In Tiny Habits, Fogg (2020) offers a fantastic technique to address motivation. We start a class discussion and create a cloud with a value inside. We list behaviors that contribute to becoming someone who exemplifies that value. Figure 13.2 shows an illustration of what our whiteboard discussion looks like:

Figure 13.2

Fogg’s College Success Cloud in Action

In the ensuing discussion, students list several behaviors that contribute to someone living out the value in the cloud. For college success, behaviors like attending class, taking notes, reading the book, and doing homework help a student experience academic success. Then we chart out these behaviors, as seen in Figure 13.3. The vertical line is effective at the top and not effective at the bottom. The horizontal (or motivation) line is “No, I can’t get myself to do this” on the left, and “Yes I can get myself to do this” on the right. Students then plot the behaviors on the chart based on the perceived effectiveness and their motivation to do them.

Figure 13.3

Charting Effective Behaviors

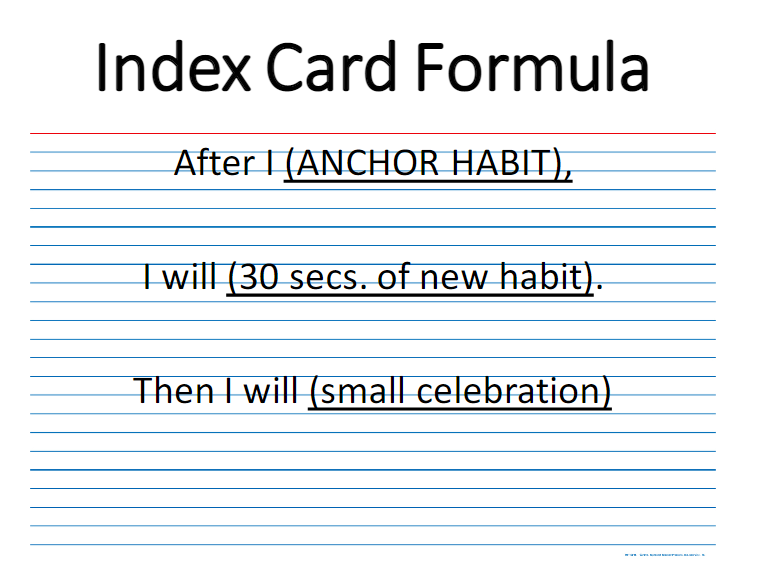

We have students focus on the behaviors in the top right quadrant with the star because they are already motivated to follow through with behaviors in that area. To develop a habit, Fogg suggests breaking it down to the smallest start (30 seconds) to something you already do (the anchor habit). To make that habit stick, he proposes adding a celebration to increase good feelings. By building on those 30 seconds, you are making it so easy to accomplish a task that you cannot say no.

In class, we hand out index cards and suggest that students develop their own habit formulas. One example is the following: “After I get dismissed from class (anchor), I will open my semester planning calendar (30 seconds of new behavior). Then I will pat myself on the back (celebration).” See an example in Figure 13.4.

Figure 13.4

Habit Recipe Assignment

In making small, positive steps, students are more likely to persist. If we ask students to change everything, they can become overwhelmed and give up. With small steps, students can experience success, which then builds momentum. Confidence increases their belief that they can accomplish this goal or task. Self-efficacy is formed. This process can be motivating when students reflect on their progress and continue to persist.

Think Flexibly

Being able to change perspectives and consider options is an important and often overlooked Habit of Mind associated with planning. “Flexible thinkers have the capacity to change their minds as they receive additional data. They create and seek novel approaches and consider possible intended and unintended consequences” (Costa & Kallick, 2008). Students can get stuck thinking that every minute of every day needs to be accounted for. That can be a big de-motivator for the planning process. People are bad predictors of the future. In Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman (2015) calls this the “Planning Fallacy.” When time is spent planning for the future, it can be hard to predict how things will go, especially when you are planning for the first time without much awareness or context. It becomes easier and better with practice, especially if flexibility is built into the system. “Stealing time” is a trap students fall into when they are not able to think flexibly. When things come up that put a wrench in the carefully planned schedule, students may decide that planning does not work.

Ultimately, time management consists of two things: tracking time and accomplishing tasks (Holschuh & Nist-Olejnik, 2011). Thinking flexibly allows students to create adjustments to their systems or their tasks. One flexible planning exercise has often been referred to as “time blocking,” where you reserve blocks of time in a weekly schedule. In USU 1020, we have students complete a weekly planning calendar to figure out how much time they must work with. One-hundred sixty-eight hours surprises students because they realize they have more time than they thought. We encourage students to make sure they have blank space in their week for unexpected events. The blank space in the schedule gives them margins to operate within. This process allows for flexibility to decide the most effective way to use their time. We compare it to a doctor’s appointment. You plan to go, but if things come up you can reschedule.

Figure 13.5

Weekly Planning Calendar

|

|

Mon |

Tues |

Wed |

Thurs |

Fri |

Sat |

Sun |

|

6:00 a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7:00 a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8:00 a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9:00 a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10:00 a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11:00 a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2:30 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11:00 p |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. From Utah State University (n.d.-d).

WOOP Goals

There is a goal-setting method called “WOOP,” which stands for wish, outcome, obstacle, and plan, that we assign to our students each week. Gabriele Oettingen (2015) shares this method in her book Rethinking Positive Thinking. Setting goals in this method helps manage impulsivity by thinking through the reasons why students want to achieve this wish and what outcomes it will provide. It also makes one determine the obstacles that stand in the way of the wish. (These can be the impulsive things that capture our attention like phone notifications or distractions.) Then students develop a plan to address the obstacle. Establishing either the same or a new WOOP goal each week helps students to be persistent in focusing on the thing they are trying to achieve. The class sets up accountability groups to keep everyone on track for the goals they have set. They can be intentional about which behaviors will make the biggest difference in their college success.

There are various ways that we encourage students to take this assignment as seriously as possible. If students turn in the same WOOP goal weekly, for instance, we encourage them to find a way to adjust the plan. Maybe the obstacle they reported is not addressing the underlying issue that is preventing them from achieving their goal. This helps them to think flexibly. In the online class we share #awards in the discussion forum after students report their progress. This is a great space to celebrate progress, share ideas, and empathize with each other. If the only progress made was writing it down, it can still earn a “#MostPotential” award. See Figure 13.6 for an example of a WOOP Goals assignment:

Figure 13.6

WOOP Goals Template

|

WOOP |

Description of Student Task |

|

Wish |

Think about the next week or two: What is the dearest wish, having to do with your college success, you would like to fulfill? Pick a wish that feels challenging to you but that you can reasonably fulfill within the next week. Write your wish in 3–6 words. |

|

Outcome |

What would be the best thing, the best outcome about fulfilling your wish? How would fulfilling your wish make you feel? Note your best outcome in 3–6 words. |

|

Obstacle |

What is it within you that holds you back from fulfilling your wish? What might stop you? Emotion? Irrational belief? Bad habit? Think more deeply—what is it really? Note your main inner obstacle in 3–6 words. |

|

Plan |

What can you do to overcome your obstacle? Identify an effective action you can take or one effective thought you can think to overcome your obstacle. Note your action or thought in 3–6 words. |

|

Plan More |

Make the following plan: If…(obstacle you named), then I will…(action or thought you named). Fill in the blanks: If ________________________ then I will _______________

|

Note. From Oettingen (n.d.).

Students have reported how successful they feel using this method of goal setting. It allows one to dream; however, it encourages a realistic look at the things that hold us back. This small adjustment can help students break down the problem and make concrete actions to address the issues that stand in their way.

Witnessing students’ creative approaches to their planning and time management has been one of the most rewarding parts of teaching USU 1020. We are inspired by original approaches, techniques, or advice shared in class. Time management almost never goes according to plan, especially on days we are focusing on that topic! The relief that comes from students when they discover or create a system that works for them means they will keep planning. They feel like they have greater control over their lives, and their stress levels go down. Our own Habits of Mind improve as we have taught this class and seen the positive effects in students’ academic and personal lives. This foundational planning course leads students to other Habits of Mind courses that explore learning strategies they can directly apply to their content-specific coursework. One of those Habits of Mind courses is USU 1060: Reading for College Success.

USU 1060 Habits of Mind: Reading for College Success

Background

It is important to understand why the expectations professors have of their students’ ability to read and dissect a text are not always congruent to the experiences and ability students possess at the start of college. Many people believe students should already know how to read critically upon their arrival to college (Bosley, 2008). Yet, the reality across many universities is that students are not reading (Sutherland & Incera, 2021). While increased demands on students’ time, such as having to work and taking care of loved ones, may factor into a student choosing not to read, another ingredient worth noting is a lack of knowing how to approach a college-level text.

During the spring semester of 2017, the City University of New York (CUNY) conducted 30 undergraduate student interviews. While interviewing students, the following was noted: university students “seemed embarrassed when asked whether they sought support with challenging reading assignments. Students…have internalized that reading is something they should know how to do already” (Smale, 2020, p. 6).

In Skim, Dive, Surface, Cohn (2021) reflected on her own experience as an undergraduate trying to complete more difficult reading assignments. She shared:

My confidence was shaken, I realized that I could no longer read well. I had to learn to read all over again. I know I was not alone in this struggle, but at the time, I felt very alone. No one talked about reading academic texts at the college or graduate school level. In fact, the last time I had even thought about reading comprehension was during high school, and even then, the conversation was cursory at best. The assumption remained that we would figure out how to read challenging texts on our own (p. 2).

Cohn’s assumption is supported by the fact that most college professors do not explicitly teach reading skills (Bosley, 2016; Sutherland & Incera, 2021). When the embarrassment surrounding a lack of reading skills is combined with hidden expectations without support, the result is a student who feels alone and overwhelmed. They do not know how to read effectively or who to ask for help. USU 1060 exists to directly address this problem by offering students explicit reading instruction.

As instructors and learning specialists, we have a shared saying: “Students don’t know what they don’t know.” This is especially apparent in the realm of reading, which is why we have our students read “Twelve Dubious Assumptions About Reading at University” by Roberts and Hamilton (2021). Students read this during the first week of USU 1060. The reading dispels many of the assumptions held by students about reading in college. Common assumptions include but are not limited to:

- Students must read everything they are assigned to read (if they skip something they will miss something valuable).

- Students need to remember everything they read.

- Students should read first then write when completing assignments.

- Students need to be fast readers.

- Students need to understand everything they read.

While the assumptions listed above seem intuitive, the truth is college students have the same constraint and affordance of any given reader, which in most cases is that they have limited time. Therefore, the key to effective reading often lies in selective reading or knowing how to discern which readings or sections of a reading offer the most valuable information to a student. The art of becoming a strategic reader has no shortcut, and we have taken various approaches to teach reading at the university level. The Habits of Mind framework is the most recent approach we have taken in our courses.

The Habits of Mind of managing impulsivity, persisting, and thinking flexibly (Costa & Kallick, 2008), as discussed in the time-management skills section of this chapter, benefit readers just as they do planners. Readers must manage impulsivity, beginning with eliminating distractions and finding an optimal environment where they can read. To persist, readers need a clear purpose for why they are reading. They can benefit by asking questions before, during, and after reading a text. Finally, university readers are required to move beyond mere comprehension of a text and toward knowledge creation. This happens when readers can make connections to the text and understand the perspectives of others in discussing any given reading.

We will now provide examples of assignments and approaches we have used in our Habits of Mind reading classes to help students hone these three Habits of Mind of managing impulsivity, persisting, and thinking flexibly.

Managing Impulsivity

Managing impulsivity in the context of reading consists of “goal directed self-imposed delay of gratification” or “the ability to deny impulse in the service of a goal” (Costa & Kallick, 2008). There is an increasing number of students taking our reading courses who suffer from attention deficit disorders (ADD) and dyslexia. These learning difficulties pose notable challenges to our students, and we believe the reading strategies we teach help these students. We also partner with USU’s Disability Resource Center (DRC) and encourage students to seek their services. The DRC can provide individual accommodations and additional resources and support to serve neurodivergent students.

The ability to manage impulsivity applies to all learners, especially in our technology-saturated age where it is common for students to read from the same devices that vie for their attention via text messages, entertainment, news, social media, and appealing alerts. The techniques of chunking and interleaving are ways we aim to incentivize students to manage impulsivity in USU 1060.

Chunking Techniques

Breaking down a large reading assignment into smaller reading chunks has benefited many of our students. Approaches such as the Pomodoro technique, where students set a timer and read for a designated amount of time before taking a break, can help students get more out of their reading by giving them time to absorb what they are reading instead of just having their eyes glaze over page after page. Chunking can also prove useful by designating a specific amount of time when students will set aside distractions to focus on reading.

In Myth of Multitasking, Crenshaw (2008) explains how humans are less efficient and more prone to mistakes and feeling stressed when they engage in what he refers to as “switch-tasking” (or attempting to simultaneously do two or more things that require our attention at the same time). This holds true for reading. A student is far better off to read for 10 to 15 minutes before taking a break to scroll social media or respond to a book or academic article. If they send text messages while “reading” a textbook chapter, their time will be wasted, as their attention will be divided.

Interleave Reading

Agarwal and Brown (2019) and Brown et al. (2018) explain the learning strategy of interleaving in their respective works. Interleaving is mixing up topics, which challenges students to compare, contrast, and discriminate the information they are learning (Agarwal & Brown, 2019).

Interleaving can apply to college reading. When students complain that their assigned course readings are boring, we invite them to read one course reading for 10 to 15 minutes and to then switch over to a course reading from a different class to read for an additional 10 to 20 minutes. Remarkably, studies have shown that our brains internalize more of what we read when we interleave our information consumption (Brown et al., 2018; Agarwal & Bain, 2019). It also becomes easier to pay attention when we are curious about what we are reading (Lang, 2020). A student forcing themselves to read a 30-page journal article will undoubtably lose interest after about 10 minutes if they find the article to be uninteresting. On average this is how long we can pay attention to something (Medina, 2008). Persistence, then, becomes a Habit of Mind that students must cultivate as they work their way through college coursework.

Persisting

Persisting in terms of reading entails igniting one’s curiosity in a text and harnessing interest toward what they are reading. Three ways we have helped students to persist in their assigned course readings are: having a purpose and asking questions; using a “Chain Discussion”; and completing a weekly reading conversation journal.

Having a Purpose and Asking Questions

In How to Read a Book, Adler and Van Doren (1972) emphasize that to read actively, a person must have a reason for reading. In addition to having a reason to read, they must also feel compelled to ask questions. Identifying a reason for reading ignites the purpose and motivation behind absorbing that information. If a student’s sole purpose for reading is that their professor assigned them to read something, their understanding of a text will be limited. Contrast this with having a clearly defined purpose, such as “We are looking at the cardiovascular system of a pig to better understand how valves of the human heart work in the example of dissection.”

Asking questions is another way for students to persist with reading. Some questions students may ask include: What does my professor want me to take away from this reading? What do I want to get out of this reading? By asking these questions before tackling any text, students will be guided in their reading, and it will become more relevant to them. Asking questions helps students get more from their reading. As instructors, we can model reading portions of the assigned text with examples of what we do before, during, and after our reading practice.

Chain Discussion Format

Online discussions in college challenge students to think more broadly about course readings or topics. Unfortunately, our experience with online discussions is that they have become a checklist item for students to complete without a lot of thought put into posts and responses. We have sought to change this, largely by developing a “Chain Discussion” approach that makes online discussions more meaningful for students.

The Chain Discussion format seeks to encourage students to persist in their reading by giving them something novel to consider in their discussion of a text. Lang (2020) reminds us that we do not simply notice novelty “but we actively seek it out” (p. 11). The Chain Discussion format is also an attempt to discourage “online discussion happy hour” where the final hour before the discussion closes becomes the liveliest. It has been our experience that most students’ first and only engagement in online discussions takes place in this hour.

The Chain Discussion serves to meet the needs of both the students and the instructor. Students, especially those taking an online asynchronous course, are time conscientious and want to participate in an online discussion efficiently, which to them is going to the discussion board once. Instructors, however, want students to persist in their online engagement.

Students in our online section of USU 1060 demonstrated persistence and anonymously reported having positive experiences with this new discussion format in their end-of-the-semester evaluations. Here is a step-by-step overview of how our Chain Discussion works:

- The instructor posts three discussion questions to the online discussion related to the topic or reading.

- The first student who posts to the online discussion board chooses to respond to one of the three questions. They restate the question in bold. Then they respond to the question in regular type. Last, they add an original question in bold, to which the next student to the discussion board will respond.

- The second student who posts to the discussion will then read everything that has been posted but only reply to the new question posed by the first student. They restate the question in bold, add their response in regular type, and then offer an original question to which the next student responds.

- This cycle continues until we reach the final student.

There are inherent incentives in place with this format to encourage students to visit the discussion early. The first responder chooses between three questions, whereas all other students only have their choice of question by selecting when they respond. If a student is unsure how to respond or does not like the most recent question posed by one of their peers, they can always delay posting to the discussion board in hopes that when they revisit later, someone else has posted a new question to respond to. Students who wait to engage in the discussion until the end have more to read, too, to ensure they are not repeating or recycling a question already asked in the discussion.

Weekly Conversation Journal

The weekly conversation journal is an opportunity for students to make connections to a text and to share their reaction to a reading. It is not intended for them to summarize or merely recap what they read to the instructor. While this might seem basic, the results have been significant among our students. They persist because it invites them to think critically about a text and formulate their own ideas as opposed to just reading with the end goal in mind of regurgitating the information on a paper or test. When students think about what they read, make connections between the text and what they know, find application for their lives, and reflect on ideas or experiences presented by the author, they are more likely to persist in their reading because it was inherently valuable to them.

We allow students a choice in how they submit their weekly reading conversation journals (i.e., written, audio, or video format). Giving students a say in how they submit this assignment helps them persist because there is freedom in choosing how they react to the text.

Thinking Flexibly

Thinking flexibly refers to “being able to change perspectives, generating alternatives, considering options” (Costa & Kallick, 2008). The following assignments are just two ways we have tried to help students think more flexibly about their reading. These assignments call for students to complete social annotations and create their own reading responses.

Social Annotations

Social annotations are an interactive way to have students annotate a text while seeing the annotations of their peers. There are different platforms available for social annotations, many of which can be added as extensions within a learning-management system (LMS). At USU, we use Canvas as our LMS, and the social annotation tool we have is Hypothes.is. To use Hypothes.is, the instructor uploads a PDF of the assigned text within the extension tool. Students can then access it as an assignment in Canvas. Students can highlight text, add comments, and see the highlights and comments of others on the PDF, all within the LMS.

A collectively annotated text helps students consider the perspectives of others as they respond to questions their peers pose regarding the assigned reading. Unlike reading responses where instructors guide students, social annotation allows students to determine what parts of the text they found interesting, useful, and important. In this sense, students become active drivers of what is discussed about a text. Students produce questions to post and generate comments in response to their peers.

Create Your Own Reading Response

A reading response is a list of questions about a reading made by the instructor that students complete to help them remember the text before coming to class, discussing the reading, or writing about what they gleaned from the text. Reading responses are a basic way to guide students through an assigned reading and something that we use in USU 1060.

Once a student becomes acquainted with the process of asking questions before, while, and after they read, we like to have them create their own reading response questions to go with an assigned course reading. They think about the questions they would ask in response to a chapter or assigned text. Then they produce both the questions and responses, moving up Bloom’s taxonomy of learning as they become innovators who create reading response questions.

Conclusion

Thinking flexibly, persisting, and managing impulsivity are the three Habits of Mind we have chosen to highlight through our experiences teaching USU 1020 and USU 1060. In many ways, Habits of Mind address the hidden curriculum of college and point to the notion mentioned previously that “students don’t know what they don’t know.” As experienced instructors and dedicated researchers in different fields, it becomes easy for us to acquire blind spots. By increasing one’s awareness of Habits of Mind and how we can best help our students cultivate these habits, we will see students succeed. As their academic achievement soars, we will find that students can not only contribute to our classrooms but also be key players and leaders within society.

After her midterm, Ana decided to enroll in Habits of Mind courses. While taking these courses, she applied strategies to help her plan out study time and to understand her assigned course readings. She engaged in these classes because she knew the strategies would help her become a more active and intentional student. Ana was able to manage her impulsivity and get the most out of her study sessions. She felt more confident entering her next exam. Her plan was made carefully, and she persisted in her classes, trusting that the Habits of Mind she developed would help her succeed. She was able to think flexibly and to become a strategic reader. She identified questions to bring to class so she could clarify certain points and deepen her understanding of readings. Because of her dedication to becoming a better learner, Ana feels a lot better about her experience in college. She has since graduated, having engaged in the Habits of Mind that lead to academic success.

References

Adler, M. J., & Van Doren, C. (1972). How to read a book. Touchstone.

Agarwal, P. K., & Bain, P. M. (2019). Powerful teaching: Unleash the science of learning. John Wiley & Sons.

Bosley, L. (2008). “I don’t teach reading”: Critical reading instruction in composition courses. Literacy Research and Instruction, 47(4), 285–308. http://doi.org/10.1080/19388070802332861

Bosley, L. (2016). Integrating reading, writing, and rhetoric in first year writing. Journal of College Literacy and Learning, 42(21).

Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L. & McDaniel, M. A. (2018). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Belknap Press of Harvard University.

Cohn, J. (2021). Skim, dive, surface: Teaching digital reading. West Virginia University Press.

Costa, A. L., & Kallick, B. (2008). Learning and leading with Habits of Mind: 16 essential

characteristics for success. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Crenshaw, D. (2008) Myth of multitasking. Mango Publishing Group.

Fogg, B. J. (2020). Tiny Habits: + the small changes that change everything. Mariner Books.

Holschuh, J. P., & Nist-Olejnik, S. L. (2011). Getting things done: Organizing yourself and your time. In Effective college learning (pp. 18–33). Essay, Longman.

Kahneman, D. (2015). The outside view. In Thinking, fast and slow (pp. 245–254). Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Lang, J. (2020). Distracted: Why students can’t focus and what you can do about it. Basic Books.

Medina, J. (2008). Brain rules. Pear Press.

Nilson, L. B. (2013). Creating self-regulated learners: Strategies to strengthen students’ self-awareness and learning skills. Sterling.

Oettingen, G. (n.d.). How can I practice WOOP?. WOOP My Life from https://woopmylife.org/en/practice

Oettingen, G. (2015). Rethinking positive thinking. Penguin.

Roberts, J. Q., & Hamilton, C. (2021). Reading at university. Macmillan Education Limited.

Smale, M. A. (2020). “It’s a lot to take in”—Undergraduate experiences with assigned reading. CUNY Academic Works (pp.1–10).

Sutherland, A., & Incera, S. (2021). Critical reading: What do faculty think students should do? Journal of College Reading and Learning, 51(4), 267–290.

Wernersbach, B. M. (2011). The impact of study skills courses on academic self-efficacy in college students [Master’s thesis, Utah State University]. All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 909. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/909

Wolters, C. A., & Brady, A. C. (2020). College students’ time management: A self-regulated learning perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1319–1351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09519-z

Utah State University. (n.d.-a). 5 day review plan. https://www.usu.edu/academic-support/files/5_Day_Study_Plan_and_Menu.pdf

Utah State University. (n.d.-d). Weekly planning calendar. https://www.usu.edu/academic-support/files/Weekly_Planning_Calendar.pdf