11 Hindsight is 20/20: The Role of Reflection in Learning

Jenifer Evers

My teaching philosophy hinges on student-directed learning, creating opportunities for student success, and depth of learning versus rote memorization. Over the years, I have experimented with different ways to assess student understanding of new concepts as well as to stay connected to individual students in a timely and effective manner. I simultaneously recognize the difficulty of accomplishing this in a manner that is not terribly time-consuming for the student or for myself. Ultimately, I created an assignment that achieves my goal using several qualities highlighted in Costa et al.’s Habits of Mind framework (2022).

As a licensed Clinical Social Worker, I had no previous teaching experience when I took my position as a Clinical Assistant Professor of Social Work at Utah State University in 2013. However, it quickly became apparent that many of the practices used by social workers with clients pertain to work with students. We meet clients where they are in their process, and we endeavor to create a professional alliance with them to support their efforts toward goals. The same is true when working with students.

Social workers must first develop a rapport and create a relationship with clients. From this foundation all work takes place, and the quality of that relationship directly impacts client success. Throughout the client–social worker relationship, the worker is responsible for meeting the client where they are. We must get on the client’s “page,” meaning that we come to understand the client’s perspective through ongoing interaction and exploration. The client leads the process, teaching the social worker about themselves and, in turn, the social worker helps the client come to a greater understanding of themselves and how they might best achieve the goals they set for themselves.

Teaching demands a similar approach. We endeavor to create a relationship with each student, even if that means that we only learn their names. We attempt to discover where students are in their learning and understanding and provide feedback based on those revelations. We create a sort of dialogue in that process. Ideally, the feedback provided by instructors influences future submissions and we continue to validate and supplement or correct understanding demonstrated in student assessment.

To meet someone where they are, whether in learning or goal-achievement, one must allow the individual to explain that to them. How do we ask students to describe their understanding? Through numerous assessments, including evaluation of written work, quizzes/exams, presentations, and so on. These tasks are often daunting and require students to somewhat separate from their own educational location due to the writing/presentation rigor. To overcome that, we might instead consider allowing students to reflect on their own thoughts regarding the material they have encountered and put thoughts into their own words. This allows students to think about their thinking and encourages them to make connections between past knowledge/experience and new information, both of which are important Habits of Mind (Costa & Kallick, 2008).

After engaging with material (assigned readings, lectures, etc.), students will find little to no difficulty providing a list of five things learned pertaining to this new material. In fact, this can usually be done in a short amount of time and with little additional effort. However, left to our own devices, we rarely take the time to intentionally reflect, despite its proven efficacy at helping us learn (Mann, 2016). Multiple studies indicate the positive impact reflection can have on academic success (Costa & Kallick, 2008; Dewey, 1944; Menekse, 2020; National Research Council, 2012; Rodgers, 2002). John Dewey (2003) noted that “we do not learn from our experience, we learn from reflecting on our experience” and explained that reflection requires us to “look back, analysing, seeing events in a wider context and considering how what we realise could be applied in the future” (p. 78). Rodgers (2002) identifies four criteria that she believes characterize Dewey’s concept of reflection along with its purposes:

- Ultimately, reflection is a process of making meaning that renders deeper understanding, encouraging connection to existing knowledge and experience.

- Reflection is a structured way of thinking rooted in scientific inquiry.

- Reflection should happen through interaction with others.

- Reflection requires that one is concerned with their own growth as well as that of others.

Costa, Kallick, and Zmuba include “Applying Past Knowledge to New Situations” in their Habits of Mind framework, which posits that finding connections between new information and past experiences reinforces learning (Costa et al., 2022). Not only does reflection have the potential to positively impact academic success; it also holds additional value for social work students (as well as those in related disciplines), specifically as it prompts students to engage in a process critical to professional development in social work, which is to reflect on professional growth and review progress with clients.

The process of ongoing reflection, an essential Habit of Mind, is one integral to social work practice (Costa et al., 2022). Certainly, the social worker routinely asks the client to reflect on their own existing knowledge of any situation they may find themself in. Examining the client experience since initiation of services accomplishes many purposes: it allows the client to recognize the change process which typically occurs in slow, incremental steps (often without notice); it provides an opportunity to assess and modify client goals, as those may need to be revised throughout the process; and it allows the worker to check in with the client regarding their satisfaction with the direction and progress of the work.

Most closely connected to this assignment is the practice of both informal and formal reflection on client progress. Similar to learning, (client) change occurs slowly and over time. This mandates that we as professionals (either in social work or education generally) highlight that process over time as well as at the conclusion of the work, either through termination with a client or end of a course. Social workers often review a client’s progress throughout the working relationship as well as at the end of it. In social work, we are required by agency and funding policies to submit reports on client progress which can take place as frequently as daily (in progress notes), weekly (in agency staffing meetings), or as long as three months (in the form of formal paperwork). This information is used to review progress and to modify treatment goals, all of which inform our continued work with the client. Often, a social worker will ask a client to identify key takeaways at the end of a session as a means of helping the client distill their insights and intentions prior to concluding. This proves useful as clients gain clarity on the value of the session and the insights gained, a process described as metacognition, another essential Habit of Mind (Costa et al., 2022).

This can hold true for students as well. When they reflect on the value of the material they read or knowledge gained from engaging with required resources and assignments, students are able to structure their thoughts and make clearer sense of them or think about their thinking (metacognition). The reflection process requires them to put into their own words the key concepts that stood out to them and allows them to make connections between the new knowledge they have gained and things they already understand and know.

In the “5 Things” assignment, students build each week on their existing knowledge and may review the compiled list to look for connections or themes. It requires them to use their own words to identify the information they choose to highlight from the material. It also allows the instructor to review the information to correct any misinformation that may exist and to add more context or content to existing material. Commenting on every student’s list each week—even if it is just one item and ideas are validated or reinforced—results in an ongoing conversation between the instructor and the student and personalizes the student experience. In this way, the students engage in the Habits of Mind of striving for accuracy (continuously trying to understand and integrate new knowledge) and persisting (grappling with what they have learned to make sense of it) (Costa et al., 2022).

Finally, requiring students to make connections in their weekly reflection asks them to draw on prior knowledge and experiences to connect with new material, which Costa and Kallick (2008) include in their Habits of Mind framework. Students gain a deeper understanding of a text when authentic connections are made. Galinsky (2010) identifies similarities, difference, relationships, and unusual connections as areas of connection that can deepen understanding. Thus, encouraging students to make connections is critical in supporting their acquisition and understanding of new information.

Both in social work practice and education, we use reflection to gain insight into the subject’s perspective and experience (or to meet them where they are). The weekly reflection assignments allow an instructor to not only understand the student perspective (which informs their learning), but to also comment on the items listed. Instructors may provide clarification if something seems to have been misunderstood, if the student seems to have remaining questions, or they may deepen the insight conveyed through a nonsynchronous form of dialogue. Questions may be posed that can prompt continued thought on a statement. Observations about connections can also be made that link items listed within the same week or over a series of weeks.

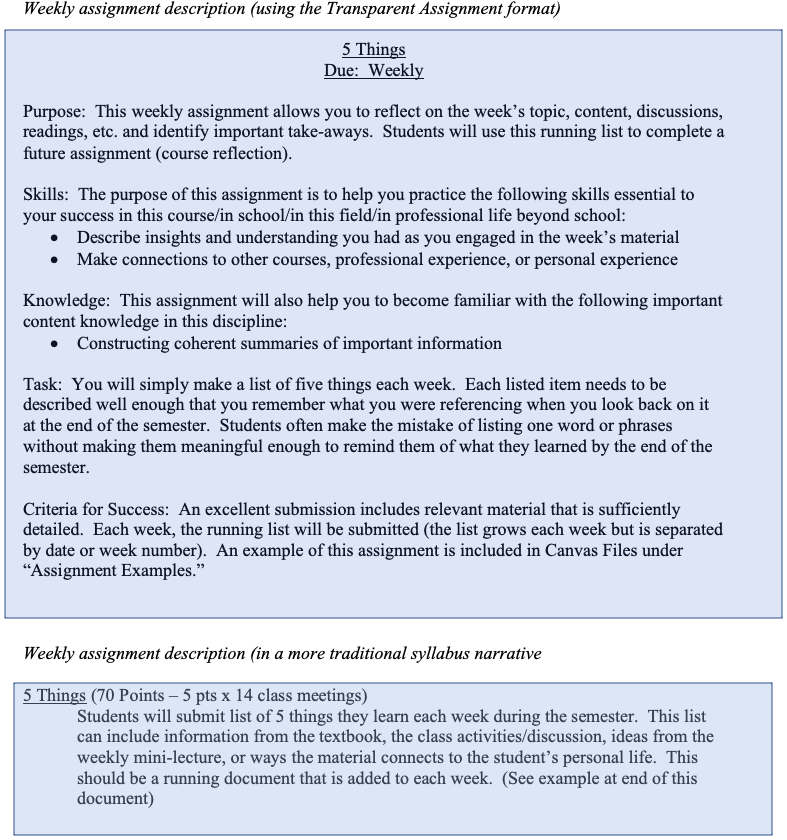

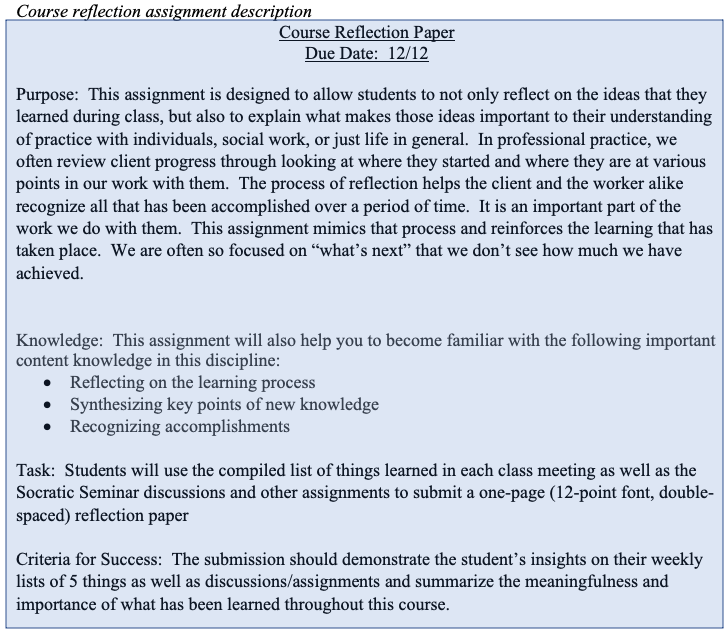

Figure 11.1

Weekly Assignment Description

Note. Using the transparent assignment format.

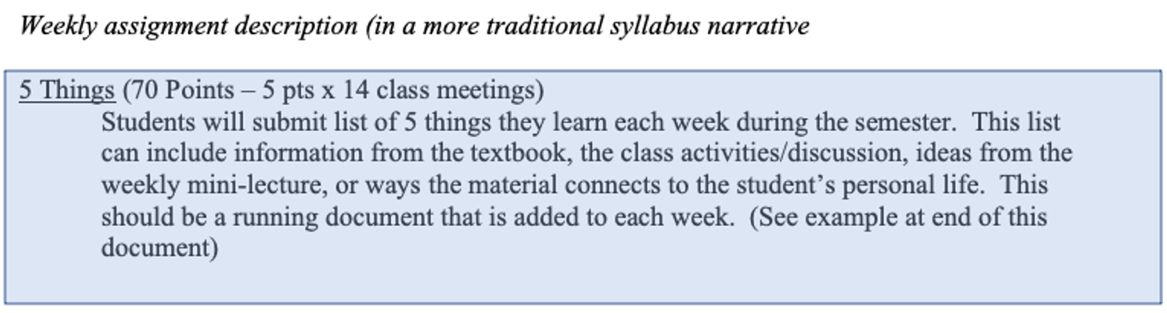

Figure 11.2

Weekly Assignment Description

Note. In a more traditional syllabus narrative.

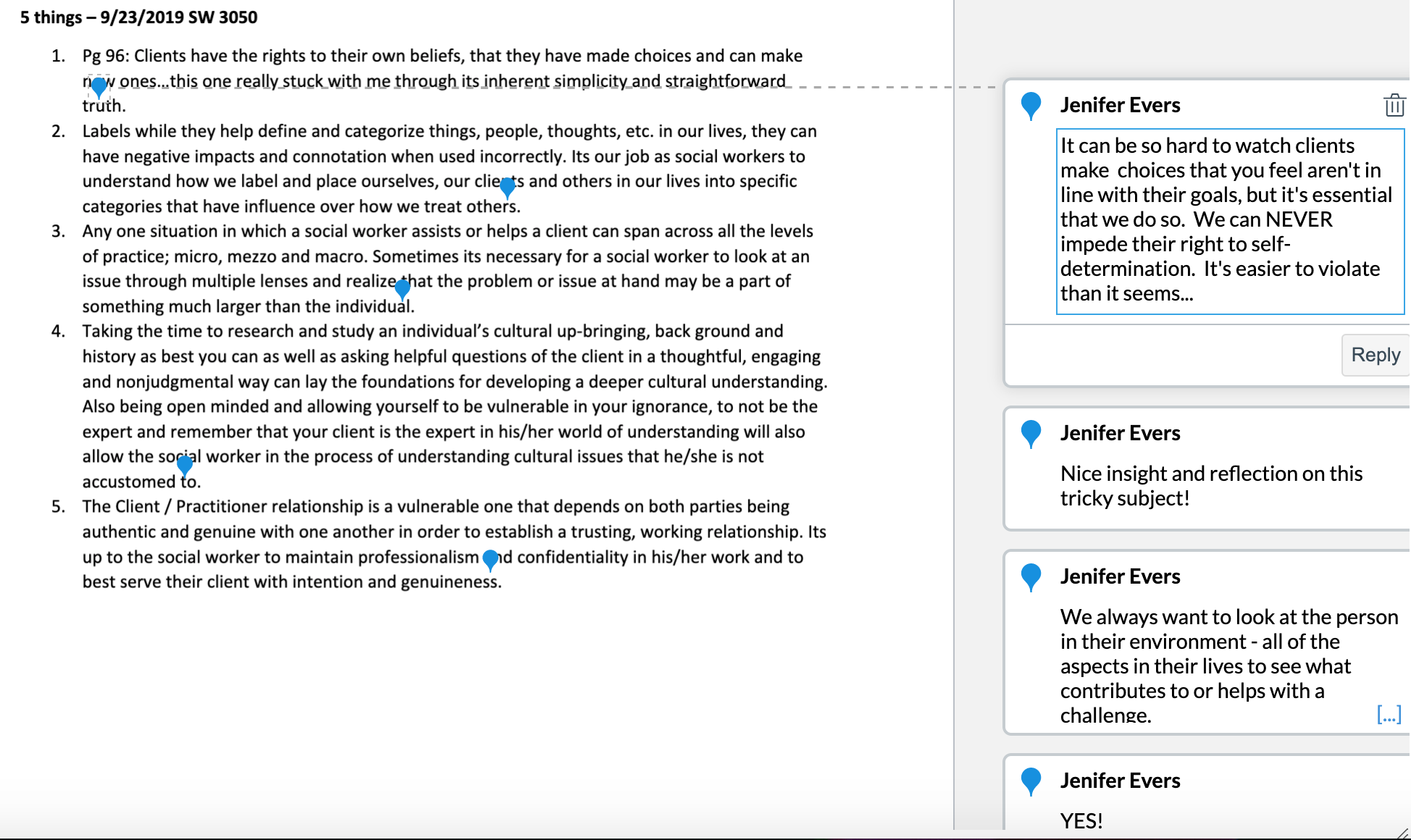

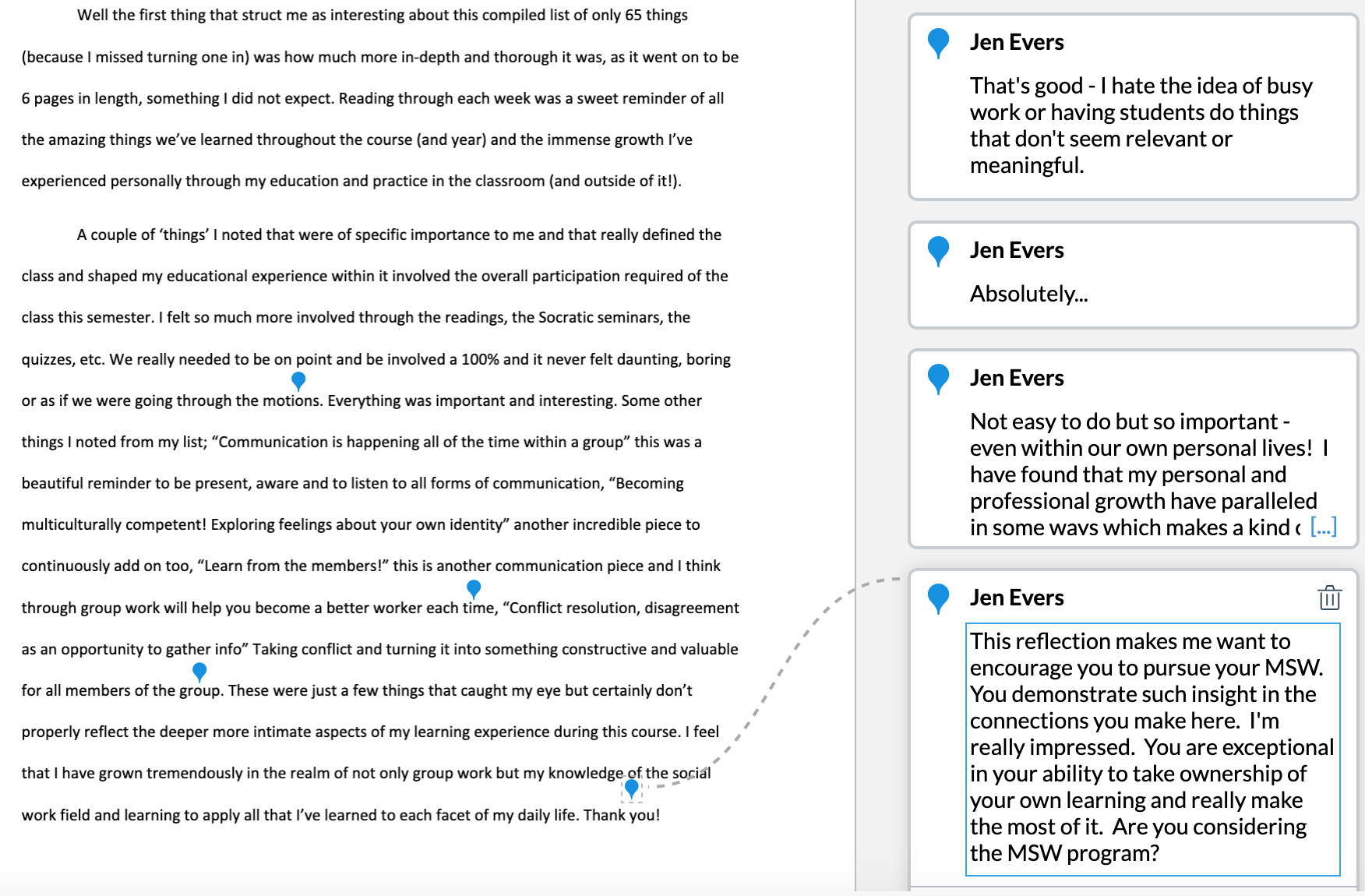

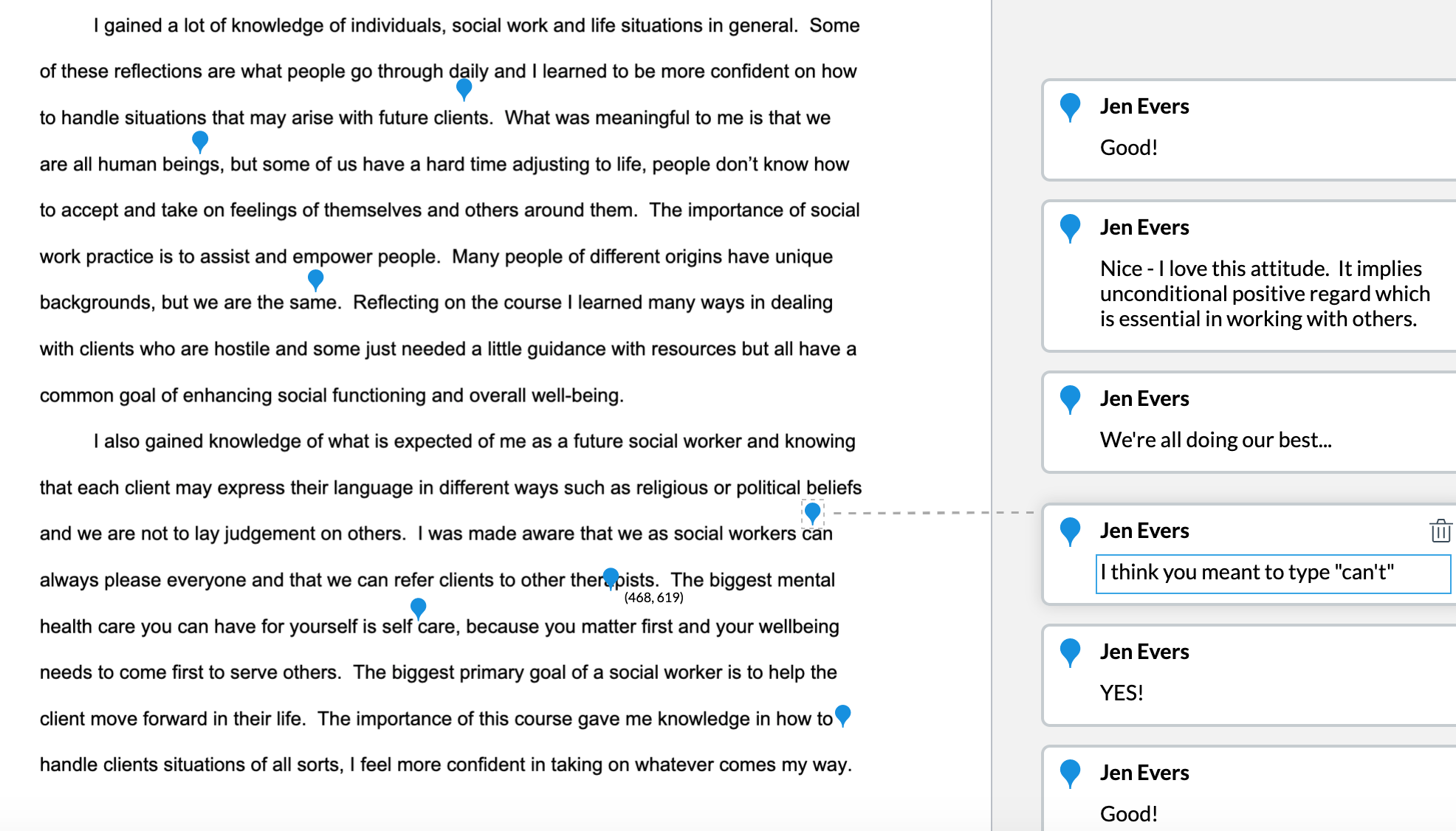

Figure 11.3

Example of Weekly Student Submissions

Note. Instructor comments on right or below.

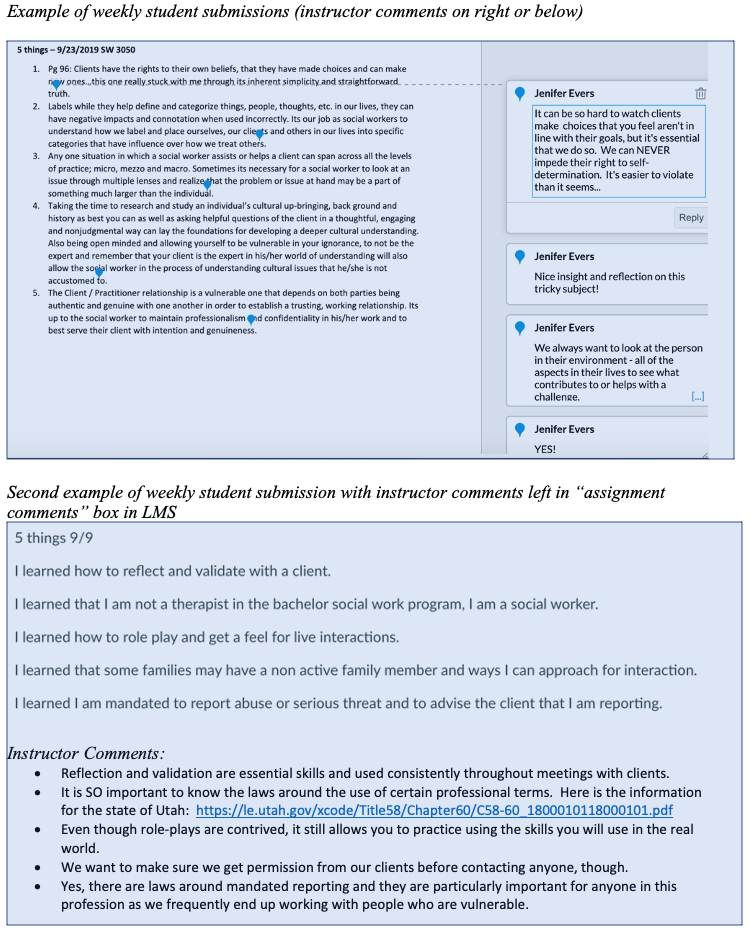

Figure 11.4

Second Example of Weekly Student Submission With Instructor Comments Left in “Assignment Comments” Box in LMS

I find grading these weekly assignments incredibly exciting, and I am often surprised by some of the student insights. The submissions vary greatly from one student to another—they might be a single sentence on each item or a full page of narrative describing a student’s insights and connections. I allow students to determine how they prefer to manage their lists. Students get out of any course what they put into it. We will always have students who submit minimal material while others go above and beyond. However, even the most minimal lists provide an opportunity for me to engage in individualized education, which has become increasingly challenging in the educational context. And, again, the purpose is to meet each student where they are and provide feedback that reinforces, supplements, or corrects ideas noted. Further, these assignments help bolster student confidence as they achieve a sense of success and deeper understanding through a relatively easy weekly assignment. Students also find the process of creating the ongoing list and the outcome worthwhile and meaningful. I receive unsolicited comments at course conclusions about how useful the comprehensive list is as students come to identify it as a resource summarizing what was learned over the semester.

Figure 11.5

Course Reflection Assignment Description

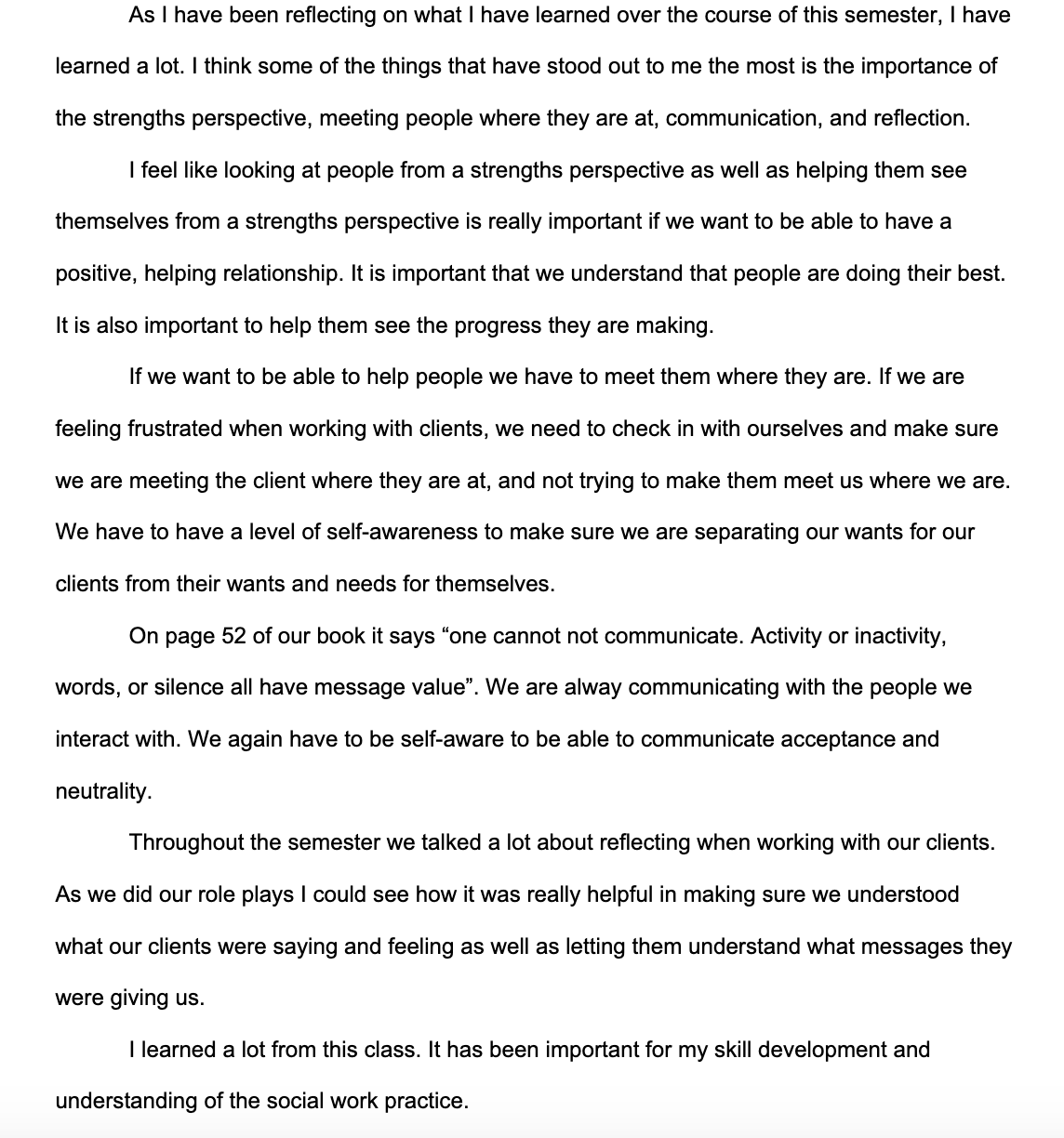

Figure 11.6

Examples of Course Reflection Student Submission Including Instructor Comments Within Submission

Figure 11.7

Example of Course Reflection Student Submission With Instructor Comments in Comment Box

Instructor Comment:

Really significant insights, (name redacted)! Your self-awareness and engagement in thinking critically about the material help you make the most of the information presented. I look forward to getting to watch you continue to grow and hone your skills next semester!

Conclusion

Grading the course reflection papers is typically a very validating experience for me and I believe it may be for students as well. I have found that my confidence in student knowledge and skills has increased significantly since implementing this assignment. Just like clients, the opportunity to look back on the experience and process its meaning and utility allows students to fully recognize the value of their own efforts and the growth they have experienced throughout the semester.

Student reflections also provide important feedback to instructors’ teaching process. They prompt us to reflect on how well we conveyed what we intended—we get a sense of whether students effectively met the learning objectives established for each week as well as the entire course. We can then clarify or supplement material to ensure that the course objectives and necessary comprehension of key concepts has been achieved to an acceptable degree to enhance readiness for future courses that build upon one another. Overall, these assignments are low cost and high reward for both instructor and student.

References

Costa, A., & Callick, B. (2008). Learning and leading with Habits of Mind: 16 essential characteristics of success. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Costa, A., Callick, B., & Zmuda, A. (2022). What are Habits of Mind? The Institute for Habits of Mind. https://www.habitsofmindinstitute.org/what-are-habits-of-mind/

Dewey, J. (1944). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. The Free Press.

Dewey, J. (2003). How we think. Dover.

Galinsky, E. (2010). Mind in the making: The seven essential life skills every child needs. Harper Collins.

Mann, K. (2016). Reflection’s role in learning: Increasing engagement and deepening participation. Perspectives in Medical Education, 5, 259–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-016-0296-y

Menekse, M. (2020). The reflection-informed learning and instruction to improve students’ academic success in undergraduate classrooms. The Journal of Experimental Education, 88 (2), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2019.1620159

National Research Council. (2012). Education for life and work: Developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century. National Academies Press. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/13398/education-for-life-and-work-developing-transferable-knowledge-and-skills

Rodgers, C. (2002). Defining reflection: Another look at John Dewey and reflective thinking. Teachers College Record, 104(4), 842–866.