9 “I’m Just Not Good at History”: Fostering a Growth Mindset with Habits of Mind

Julia M. Gossard

One of the most common frustrations I hear from students in my large-enrollment history survey, HIST 1110: European History from 1500, is that they have “never been good at history.” Having taken numerous history courses during their K–12 education, many of which have focused on the rote memorization of dates, names, and facts about the past, students can arrive to HIST 1110 with an apathetic—or even a negative—disposition toward history as an academic discipline. They were not able to remember historical details in past learning environments, so would a college history course be any different?

When students believe that success in a particular academic subject is an innate characteristic, they can resign themselves to accept that they may perform poorly in that subject. Known as a “fixed” mindset, Dweck (2010) and Duckworth (2007) have explained that students stuck in this mindset lack the persistence to be successful in the face of adversity (Dweck, 2010, p. 16). This is especially true in online asynchronous courses where students must take control over their learning, which effectively allows them to push off work in courses in which they have a fixed mindset (Hochanadel & Finamore, 2015, p. 48). Additionally, many online students, without the physical classroom and the community that space can build, lack perspective that academic success is not necessarily innate to an individual, but something that must be practiced and honed over time.

To help students develop a growth mindset and better skills around learning—even in those courses that they do not find inherently or immediately interesting—I created a series of extra credit assignments focused on various Habits of Mind in European History from 1500. These assignments are reflective in nature. Each provides students training and guided content on a particular Habit of Mind. Students must reflect on what they learned and apply new strategies to coursework in HIST 1110 (or another one of their courses). In doing so, students develop Habits of Mind, including persistence, applying past knowledge to new situations, thinking about your thinking (metacognition), and thinking flexibly. While some students may always be disinterested in history, these Habits of Mind assignments can help them develop the skills and academic dispositions to persist through and succeed in college learning.

This chapter examines two of the Habits of Mind extra credit assignments in HIST 1110: “Growth Mindset” and “Confidence in Learning.” In the following, I detail the assignment instructions along with explanations of how these extra credit opportunities help to grow students’ Habits of Mind. Student reflections are interspersed to demonstrate the impact these assignments have had on students’ perceptions of their learning.

Fixed Mindsets in HIST 1110

HIST 1110 carries a Breadth Humanities (BHU) general education designation at Utah State University (USU). As such, most students enroll to earn credit for this graduation requirement. While students have ample choice (with over 30 courses currently listed in the USU catalog as “Breadth Humanities”), students often arrive with little to no interest in the subject matter. Unsurprisingly, my online sections of HIST 1110 carried a 27.6% DFWI rate in fall 2020 and spring 2021. This is higher than the national DFWI average of 25.1% for introductory history courses (Koch & Drake, 2019). That means that out of the 180 to 200 students enrolled each semester, up to 50 received a grade of D, failed, withdrew, or received an incomplete for the course. Although this DFWI rate may have been inflated because of significant personal and learning struggles resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic, it was still something that greatly concerned me.

Therefore, in preparation for summer 2021, I significantly revised HIST 1110 with an eye toward student success, eliminating assignments that some students perceived as “busy work.” Instead, I developed assessments that allowed students to immediately apply their content and analytical knowledge (Gossard, 2022). Reading through qualitative feedback provided on IDEA evaluations, Rate My Professors, and student correspondence with me, I recognized that many students who struggled in the course needed help honing their learning skills and academic dispositions. A comment I kept seeing was that a student “didn’t like,” “wasn’t interested in,” “wasn’t good at,” or “hated” history. These students reported that they did not make time for the course in their busy schedules because they had already resigned themselves to failure or struggle.

These students displayed a fixed mindset around history. Regardless of how well I scaffolded their learning, aligned my assignments to course outcomes, or provided students autonomy in learning, these students may not succeed because of their fixed mindsets. As pedagogical research on motivation has demonstrated, students tend to perform and learn best when they are engaged in material that they find “enjoyable or interesting” (Kickert et al., 2022). While I knew that I could not make everyone into a “history nerd” (or even find enjoyment in watching my mini-lectures in which I don a tri-corner hat and other costumes), I could help them find relevance in the subject matter, develop strategies to persist in learning, build their confidence, and grow their motivation to succeed by focusing on various Habits of Mind. From this realization, Habits of Mind extra credit assignments were born.

Developing a Growth Mindset

Costa and Kallick (2008) define their Habit of Mind “persisting” as “seeing a task through to completion” (loc, 195). When examining the Canvas analytics of students who received a D, F, or Incomplete1 in fall 2020 and spring 2021, I noticed that 84% of these students started the course strong, completing assignments from Week 1 by the first due date. But by Week 2, only 21% of those students completed coursework on time. A month later, in Week 6, less than 1% of the students who earned a D, F, or I were regularly completing coursework. Some stopped logging into the LMS altogether. These students were disengaged and not persisting in their learning.

When I reached out to some of these students, they conveyed different reasons for their insufficient engagement with the course. Some expressed frustration with their lack of motivation. Others explained that they had more important courses to complete and HIST 1110 had to take a backseat. Most frequently, though, students lamented that they had always been bad at history and, therefore, were avoiding HIST 1110. I empathized with this observation, as I often thought of myself as bad at math and science. I struggled with both in college, and I had to repeat two classes to earn general education credit for them. I understood the struggle my students were experiencing.

This struggle can come from what Carolyn Dweck (1999, 2007, 2010) and Angela Lee Duckworth (2007) have popularized as a “fixed mindset” around intelligence. Students who think of “intelligence [as] inherent and unchangeable exert less effort to succeed” (Hochanadel & Finamore, 2015, p. 47). Those who believe that intelligence in a particular subject area is “a malleable skill,” though, are much likelier to succeed (Hochanadel & Finamore, 2015, p. 47). But this is not done without determination. As Duckworth (2009) has explained, students who “persevere when faced with challenges and adversity” have “grit” (Hochanadel & Finamore, 2015, p. 47). Costa and Kallick’s (2008) Habit of Mind of persisting embodies this ideal, encouraging students to develop academic dispositions and skills to push themselves to succeed.

Reflecting on this, I recognized that my students needed assistance to grow skills around persistence and grit. I created an extra credit assignment titled “Growth Mindset” that introduces students to the concept of fixed and growth mindsets. This assignment asks students to reflect upon their own learning and to come up with a list of action items they can apply to HIST 1110 (or another course) where they may present a fixed mindset.

The first part of the assignment guides students through the concepts of fixed and growth mindsets. I adopted terminology that students could easily understand and relate to instead of providing pedagogical jargon. I distilled Dweck, Duckworth, Costa and Kallick’s ideas about mindsets and persistence in learning (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1

Growth Mindset Instructions (Part I)

After students read this brief introduction to a growth mindset, I ask them to watch a short YouTube video from John Spencer titled “Growth Mindset vs. Fixed Mindset.” This video further explains the importance of developing a growth mindset. After that, students must pick one to two courses they are currently taking in which they want to develop a growth mindset. I ask the students to thoughtfully explain in a paragraph of at least six sentences why they feel like they have a fixed mindset in that course. In doing so, I encourage the students to engage in an important Habit of Mind, thinking about your thinking (metacognition). I pose a series of questions to guide students through the process of metacognition:

- What about the listed course(s) do you find most challenging and why?

- Are some of the things you find most challenging about the course in your control or out of your control? Something that may be out of your control is the time a course is offered, its modality, or its location on campus. Things that may be in your control include how much time you devote to the course, for instance.

- How has your fixed mindset impacted your grades and feelings around the course(s)?

- Have you struggled with this subject or content material in other educational settings?

- If so, how did you overcome those struggles, if you did?

- Are there activities and/or patterns of thinking you’re engaging in with this course that are impeding your success? (For example, are you actively avoiding it? Are you continually missing homework assignments? Are you completing assessments while grumpy?)

- Why is it important to succeed in the course(s) you mentioned? Think beyond just getting a good grade or completing a general education requirement (though both can be important). What does this course offer to you as a 21st-century global citizen?

Although students do not need to answer all these questions in their paragraph, each question can assist students to dig deep. The purpose is to get students thinking about their own habits, their skills, and the course’s relevance to their degree plans and lives. While the process helps students develop the Habits of Mind of persisting and metacognition, it also asks students to apply past knowledge to new situations. By making students think about how they have previously developed strategies to overcome academic adversity, this can help them develop creative solutions to their current problems. Additionally, if they were not successful in a previous situation, it may push them to want to succeed this time.

Metacognition can be an important skill to develop to help students not only persist in their academic careers but also in their postsecondary futures. When done well, developing metacognitive skills can be a transformative experience for students. For example, in spring 2022, a student remarked that

I never thought about my learning before. I’d always just blamed my teachers and my parents and dint’ [sic] think about how what I’m doing or not might be part of the problem. Even tho [sic] I may never really enjoy statistics I can see how it’s important to my future in business. I’ve got to figure it out. I’ve also just really been procrastinating in it which is making me more stressed out than if I just did the assignments. I need to think about some of my other classes too because I think I might be having similar problems.

In this case, the student had never practiced metacognition before. They had not taken autonomy over their learning. By completing the growth mindset extra credit assignment, they were able to think about how to relieve stress in their lives while also persisting through learning.

Similarly, another student wrote the following in their “Growth Mindset” assignment:

I’m seeing that my brain is the biggest problem to succeeding in HIST 1110 because I’m just not giving myself the time to do the work even though I technically have the time in my day since I don’t really like history.

This student recognized that their lack of time management was impeding their ability to complete work. In both instances, this exercise in metacognition helped students take responsibility for their learning and overcome several hurdles regarding motivation, time management, and completing their coursework.

Although thinking about your thinking is an important first step for developing a growth mind, nothing will improve unless behavior changes. The third part of the assignment tries to nudge students to action. It asks students to identify three action-oriented ways that they could start to change to a growth mindset. I give them ideas, including:

- assessing time-management plans and intentionally making time for the course;

- establishing personal rewards for completing assignments;

- asking a friend to help as an accountability buddy and/or form a study group;

- going to the Disability Resource Center to get official accommodations for a learning disability;

- reading through recent feedback and rubrics, making sure I understand why I received the grades I did;

- reaching out to the professor or teaching assistant during office hours to identify common problems; or

- attending a supplemental instruction (SI) or recitation session to better understand the material.

This assignment opens in Week 4 of the course. I encourage students who have not completed work or who have not been keeping up well by Week 7 to complete it. Most students complete the assignment in Weeks 8 and 9 of the spring and fall semesters and Week 7 of the summer semesters. This corresponds to midterm examinations and, as such, students taking stock of how their semesters are shaping up.

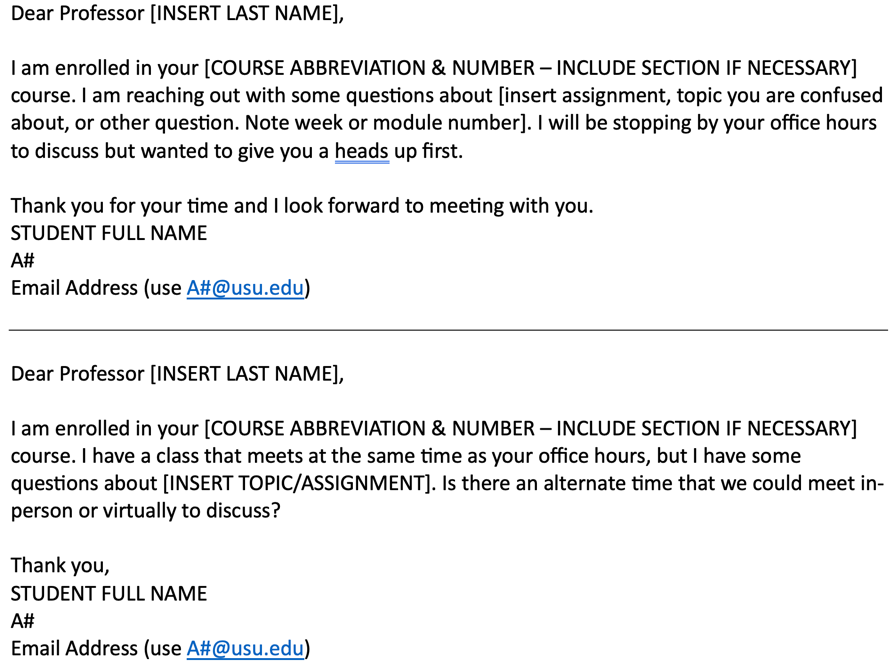

Out of 239 students who completed this assignment between summer 2021 and fall 2022, the most common plan students make is to visit with their professor during office hours to ask for assistance in navigating the course. As part of additional resources in this assignment, I provide students with email templates to contact their professors for help (Figure 9.2). These have been downloaded and viewed 407 times, indicating that at least some students are using them or drawing inspiration from them.

Figure 9.2

Email Templates

The second most common action plan that students list involves what might be described as overcoming a mental block (or “getting over yourself”). One student stated, “Why am I sabotaging myself? This is so stupid that I keep making it harder for myself.” Another remarked, “Honestly…I need to just get over my fear of this class and just do the damn thing.” A third student wrote they “needed to have the time and space to assess how I am continually setting myself up for failure.” They recognized that there are challenges, sometimes self-imposed, that hold them back from completing a task, assignment, or course. By engaging in metacognition, students start to develop a growth mindset. In these three responses, students demonstrated their understanding that developing the important Habit of Mind of persistence would be crucial for their success in HIST 1110.

“Growth Mindset” is a high-value extra credit assignment. It can provide students up to 10 extra credit points on a major course assessment that is graded out of 100 points. Students who have missed or scored poorly on assignments are very incentivized to complete it. While high-achieving students also complete this assignment, 58% of the students who have completed it are scoring in the C and below range when they submit the “Growth Mindset” assignment.

Confidence in Learning

Since the “Growth Mindset” assignment asks students for three action items to complete, I created a follow-up assignment to assess how students have, or have not, made progress on developing a growth mindset and persisting in learning. There were 239 students who completed the “Growth Mindset” assignment between summer 2021 and fall 2022. There were 174 students from that same period who completed the follow-up assignment, “Confidence in Learning.” Much like “Growth Mindset,” this assignment is a high-value extra credit assignment, carrying up to 10 points. Only students who turn in “Growth Mindset” can complete this follow-up assignment, which opens in Week 10 of the fall and spring semesters and week 9 of the long summer semester.

“Confidence in Learning” has four parts to it. First, students must go back to their “Growth Mindset” assignment and determine if they completed the action items they listed and explain why or why not. Lower stakes action items like contacting the professor for help, going to an SI session, or using the Writing Center, tend to be completed the most between the assignments. A student reflected that “I was so surprised how helpful my professor was when I asked him for help. He introduced me to my teaching assistant and they both helped me understand water-borne pathogens way better. I’m not scared of the teachers anymore.” This student also remarked that because they had formed a connection with the teaching assistant and professor, they were “excited to do homework.” In many ways, this assignment helped them, the professor, and the teaching assistant humanize each other more. They added, “I’m getting more personal feedback on the assignments now too which makes me feel like I matter.”

While most USU instructors are there to help their students succeed, I have had a few students reflect that their professors were less helpful. One student reported that when they emailed for clarification on an assignment, their professor replied 2 weeks later (far after when the assignment was due) with a one-line answer directing them to the textbook’s online learning modules. The student explained those modules “did not clarify the professor’s assignment.” Despite that negative interaction, the student did find helpful materials for other assignments in the textbook’s online learning modules and earned a higher grade than anticipated on an exam after taking a practice test. In this case, the student was able to develop their Habit of Mind of thinking flexibly. As Costa and Kallick (2008) define it, thinking flexibly involves “look[ing] at a situation another way” (loc. 200). Even though this student did not get the interaction they hoped for from the professor, they were able to think flexibly and to persist on their way to academic success.

The second part of “Confidence in Learning” involves students explaining which courses they feel most comfortable with or confident in and why. This part of the assignment provides students the opportunity to reflect on the skills and content they are best at. Instead of focusing only on the negativity of a fixed mindset, students can also celebrate their achievements in other courses. As part of this step, I also ask students to assess why they are doing so well in those courses and if there are actions, attitudes, and habits they have developed around those subjects that they could use in other courses. For instance, one student wrote, “I’m probably spending too much time on my linguistics homework because I really love it. It’s like a code that I’m trying to break. My computer science homework is hard but it’s also like a code so I need to think about it that way too.” In this instance, the student tried to adapt their same enthusiasm for one course to another.

The third and fourth steps of “Confidence in Learning” are related. These steps require students to develop time-management strategies. In the third step they must list all the remaining assignments they have to do, along with target grades for each in order to pass or achieve the grade they want in their courses. Then, in the fourth step, students must plan these assignments out on a calendar, breaking down the steps to each assignment. I encourage them to think about additional resources like the Writing Center, professors’ office hours, and using techniques like Pomodoros to help them complete assignments. By providing students a space for intentional time management, the assignment tries to encourage them to plan for success. A student wrote on an IDEA evaluation that “making me create a plan for the end of the semester was the only thing that kept me on track in the last three weeks of the semester.” This had a real and effective impact on their academic success.

Conclusion

The impact of these Habits of Mind extra credit assignments on student learning outcomes is apparent in both qualitative and quantitative teaching assessments. By the numbers, there has been a clear impact on student performance after introducing Habits of Mind assignments. Since these assignments were implemented in summer 2021, HIST 1110’s DFWI rates have steadily dropped to 18.2%. Although I would like these to drop further, this is lower than the national average and demonstrates a significant increase in student resiliency and achievement. In addition to the quantitative evidence, students regularly reflect on the positive impact of these assignments on evaluations. While none have proclaimed that they now love history, they have articulated that developing growth mindsets, study skills, and better dispositions around their courses have significantly helped them. For example, in spring 2022, a student wrote on the IDEA evaluation that they “sincerely appreciated the emphasis put on practicing some skills that I should have learned in high school and community college but for some reason I didn’t.” The student explained they were a nontraditional student, coming back to school “after nearly ten years working random jobs.” They had failed two classes, including HIST 1110, their first semester back. But in spring 2022, they adapted the Habits of Mind assignments and strategies to each of their classes. The student continued: “I’m gonna [sic] pass all my classes this time and feel like I can really do this.” For this student, Habits of Mind extra credit assignments helped reveal the “hidden curriculum” of college, develop persistence in learning, and made the student realize higher education was for them.

In both assignments, students develop important Habits of Mind, including persisting, thinking about your thinking (metacognition), and applying past knowledge to new situations, while also working to develop what Dweck (2010) and Duckworth (2007) have labeled a growth mindset. By doing so, students can take ownership of their learning and make impactful changes to their academic dispositions and study skills.

References

Costa, A., & Kallick, B. (Eds.). (2008). Learning and leading with Habits of Mind: 16 essential characteristics for success. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Costa, A., & Kallick, B. (Eds.). (2009). Habits of Mind across the curriculum: Practical and creative strategies for teachers. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Duckworth, A. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087.

Duckworth, A. (2009). Development and validation of the short grit scale (Grit-S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174.

Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press.

Dweck, C. S. (2007). The perils and promises of praise. Educational Leadership, 65(2), 34–39.

Dweck, C. S. (2010). Mind sets and equitable education. Principal Leadership, 10(5), 26.

Gossard, J. (2022, November 8). Active learning in the online classroom: Apply knowledge activities. W.W. Norton’s Learning Blog. https://nortonlearningblog.com/archives/2589

Hochanadel, A., & Finamore, D. (2015). Fixed and growth mindset in education and how grit helps students persist in the face of adversity. Journal of International Education Research, 11(1), 47–50.

Kickert, R., Meeuwisse, M., Stegers-Jager, K. M., Prinzie, P., and Arends, L. R. (2022). Curricular fit perspective on motivation in higher education. Higher Education, 83, 729–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00699-3

Koch, A. K., & Drake, B. M. (2019). Digging into the disciplines II: Failure in historical context—the impact of introductory U.S. history courses on student success and equitable outcomes. Gardner Institute.