7 Learning Beyond Content: Using Weekly Reflection to Promote Student Confidence and Lifelong Learning

Nichelle Frank

During an intake survey in my introductory-level history courses, my students select from a series of answers to respond to the question, “What do YOU believe are the goals of a college-level history class (select ALL that apply)?” The possible answers are “teach information about people, places, and events in the past,” “teach critical thinking skills,” “practice oral communication,” “practice written communication,” “memorize lists of dates and facts,” and “expose students to diverse points of view.” I have used this question as part of a pre-course assessment since fall 2021. The top three answers, which 70% (or more) of the students select as course goals, are “teach information about people, places, and events in the past,” “teach critical thinking skills,” and “expose students to diverse points of view.” Coincidentally, these are some of my goals in teaching the course as well, and I developed a low-stakes reflective writing assignment that has increased student confidence and provided students with the transferable skill of taking initiative in their own learning.

The beginning of my career as a tenure-track professor coincided with the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result, the pandemic and its learning environments have shaped much of my pedagogy. Since the pandemic created new types of learning environments, students now need new skills to be successful. As such, I built courses that used a method of instruction to allow students time and space to process new content and encourage new ways of thinking about that content. The latter—a form of metacognition—is an important step in successful learning, as Roediger et al. (2014) describe. Moreover, once students understand their own learning, they can better apply the skills and methods they learn in one class to another and then from classes to day-to-day life. This “transferability,” based largely on Perkins and Salomon (1988), motivates students to participate actively in the reflective process, not just in their classes but in other aspects of their lives. Motivation to complete work is particularly significant in the Covid and post-Covid learning landscapes because students are learning in different modalities that require them to be self-motivated and take ownership over their own learning.

This chapter demonstrates that incorporating brief, informal, weekly written reflection into college classrooms helps students form healthy Habits of Mind in at least two key ways: First, it gives students ownership over their learning and, second, it boosts their confidence in their ideas and academic abilities. When adjusted to be outward-facing, as in a class discussion, reflection assignments also foster students’ sense of a learning community in which they collectively produce historical knowledge. In achieving these outcomes, this assignment structure addresses the Habits of Mind of thinking about your thinking, listening with understanding and empathy, thinking flexibly, and thinking and communicating with clarity and precision.

Weekly Response Paper

Since fall 2020, I have been teaching several introductory-level history courses, and I have used short, reflective written assignments every semester. While I have taught these history courses in various delivery methods (e.g., in-person, via Zoom, and asynchronous online), the requirement of a short reflective assignment has remained consistent across modalities. What I have changed over time includes the assignment directions and how students submit the assignment within Canvas. These changes have increased student ownership over their learning by giving them autonomy as well as placing them in forums where they must find ways to communicate their ideas clearly and respectfully.

The assignment’s earliest variation was a “Weekly Response Paper,” which I employed in both HIST 1700: American History and HIST 2710: United States, 1877–Present. Students had to write a response by the end of each of the semester’s 15 weeks. These responses counted as 20% of students’ final course grades. The large percentage signals to students that this is an important part of their success in the course. I dropped each student’s two lowest scores. The assignment directions were:

Write a short, informal response to the week’s materials, including reading, lecture, and discussion. Your response must be 100 words minimum. The goal is for you to reflect on what you learned this week. Was something completely new information to you? Did some of the sources challenge your thinking on a topic? How does the week’s materials connect to other things you have learned about the topics covered that week? How will you use the information you learned this week in your life? This will be graded pass/fail.

Responses to these questions helped me understand the challenges students faced in U.S. history surveys. For one, I noted that students were encountering a great deal of information each week and needed a low-stakes space to sift through and process that information. Although the cumulative responses represented a large portion of their grade, the demands of each individual assignment were low.

The results on these assignments in fall 2020 were generally what I had hoped. Students named topics and examples that caught their attention and described how these examples felt important to them. Each week, students participated in two class meetings (either in-person or via Zoom). These class meetings combined lecture and discussion, which built on the primary and secondary source readings that students completed before attending class. This provided students with myriad topics to discuss in their weekly response papers. In the second week of class alone, students wrote about subjects ranging from death and disease in the colonial period, the variance in relationships between Native Americans and Europeans, and their shock at seeing a timelapse video portraying the number and frequency of ships moving enslaved people from Africa to North and South America. Rather than me dictating their learning, students were telling me about what they had learned and how that compared to any previous knowledge they might have had on the subject.

This first iteration of the assignment worked well for my purposes but needed adjusting to help more students grasp the benefits of precise language and specific examples. I addressed some of this lack of precision and specificity in feedback to individual students, and there was improvement moving forward. For example, a student might simply state that they liked learning about a topic but not explain further why they liked it or what it meant to them on a more personal level. Additionally, students sometimes only summarized a topic. In such instances, I provided feedback to prompt greater specificity and historical thinking, such as, “For future weekly responses, aim to include more details, such as specific people, organizations, events, or places that you learned about.” With students who only summarized content, I encouraged them to reflect on how the information might inform the way they think about their own lives. By the end of the semester, students who had not initially comprehended the idea of going beyond summarizing were submitting responses that included direct quotes from primary sources and noting either change over time or continuity, which are two core concepts that animate my discipline.

There were additional improvements that students made over the course of the semester. These included students describing how they were sharing the information they had learned with friends or family. Some students even used what they were learning in the course to open conversations about big topics, like the Vietnam War and immigration policy, with the people in their lives.

By using more precise language and historical details, students demonstrated stronger communication skills. By selecting the topics that most resonated with them and by sharing with their friends and family, students were also participating actively in their own learning. They were thinking about their own thinking, as the Habits of Mind framework describes.

As I observed the submissions for these papers during that first semester, I wondered how these students might share their thoughts with one another. While in-class discussion provided some opportunity to do this, it was difficult and perhaps even unfair to require in-class participation during the height of Covid. I was also cognizant of future instances where I would be teaching asynchronous online courses. Was there an assignment that might work well for all these delivery methods? The weekly response paper was a solid beginning, but there was room for improvement and growth. I had to find a way to work around both the limitations of remote learning and teaching in different delivery methods, sometimes multiple delivery methods at once (e.g., a combination of students attending in-person and via Zoom during a single class session plus students missing class and catching up by watching a recording later).

Revised Weekly Journal Discussions

While the first version of the assignment clearly helped students take initiative in their own learning, there was less evidence that they were seeing the transferability of that skill. As my delivery method for courses shifted to include more Zoom and asynchronous online classes, I wanted to foster some of that transferability through student-to-student engagement. While I had maintained strong instructor presence in pre-pandemic online teaching, I was also aware that a balance was necessary; too much instructor presence might be a detriment to online learning (Blackmon, 2012). Additionally, although studies support the notion of a strong instructor presence in online learning, the isolation students experienced during Covid-19 prompted me to search for ways to increase student-to-student interaction (Conaway et al., 2005; Filho et al., 2021; Lieberman, 2019). Finally, student-to-student engagement would be a way to nurture a stronger sense of a learning community in remote learning environments (pandemic or not), as described by Conaway et al. (2005).

To improve the assignment’s ability to teach transferable skills, I revised the assignment to be a version of a class discussion board. Although online discussion boards are common in higher education, I wanted to avoid the format I had used in pre-Covid asynchronous online courses, which relied on reading comprehension–style questions. In course evaluations, students stated that they enjoyed these discussion boards to a degree, but the repetition in answers and a stilted conversation in the responses peers offered to one another had me speculating about their overall utility. On the one hand, this common version of discussion format lent to reading comprehension and written communication. On the other hand, it limited discussion topics. Although I was unfamiliar with the Habits of Mind framework at the time, what I was really looking for was a way to encourage the Habit of Mind of “responding to the material with wonderment and awe. “What if I let students have a little more control over these discussion boards? What if instead of asking “What did you learn about xyz?” I instead said, “Tell me what you learned this week”?

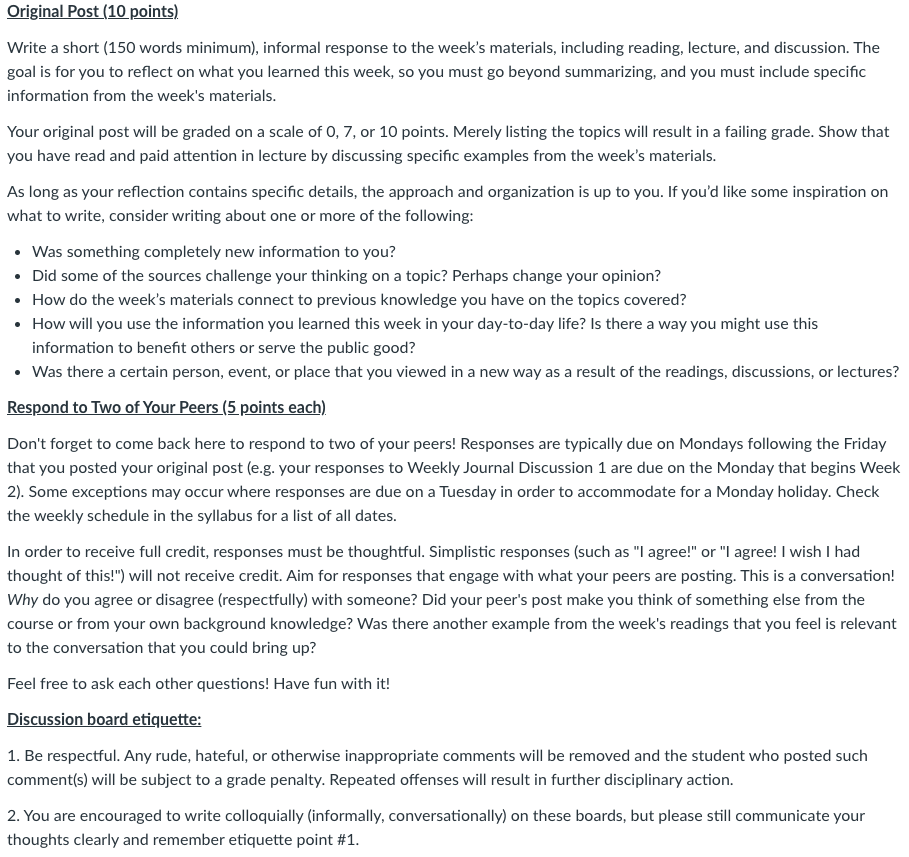

With these thoughts in mind in spring 2022, I replaced the weekly response papers with a weekly discussion board while shifting my introductory-level courses to an asynchronous online delivery method. I modeled the boards on the “Weekly Response Papers” I had used since fall 2020 rather than on a reading-specific prompt. While the response paper achieved several learning objectives, structuring the assignment as a response “paper” risked the assignment sounding more formal and restrictive than intended. Moreover, only I read the insights that students submitted. Shifting the assignment to a discussion board and retitling it “Weekly Journal Discussions” exposed students to other reactions to the materials and invited them to approach the assignment with a more thoughtful mindset (thus why I introduced the word “journal” to the title). I am sure I am not the first to do this, but my observations below demonstrate how this type of assignment has worked in a new, pandemic-influenced learning landscape. The Weekly Journal Discussions directions are found in the Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1

Weekly Journal Discussions Instructions

These instructions remained the same every week so that students had a consistent learning opportunity throughout the semester. When compared to the previous set of directions for the “Weekly Response Papers,” these directions are more robust, include a slight increase in the minimum word count, and encourage proper discussion board etiquette.

In addition to making this assignment a discussion board rather than a paper, I split my courses (ranging between 40 and 100 students) into discussion groups of four to five students and set the discussion groups to change every 5 weeks. I assigned students (randomly) to their groups using the Canvas sorting feature. These settings allowed students to get to know each other in smaller online learning environments and avoided the groups getting “stale.” I also set the discussion boards so that students must post their own work prior to seeing posts from others in the group. I piloted this in an asynchronous online class in spring 2022 and then in a Zoom-based class in fall 2022.

This “Weekly Journal Discussions” version of the assignment led to several developments that speak to the Habits of Mind framework. For one, there was greater detail in responses, which reflects thinking and communicating with clarity and precision. Although the change in the minimum word count from 100 to 150 might explain some of the increased detail in written work, responses were consistently over 200 words, and often 300 or more. In other words, students were exceeding expectations. Even the shortest responses were 160–170 words long. Although some students occasionally included “filler” words and comments, most were specific and included detail. For example, students might summarize something like the Haymarket Uprising and then describe how that example informed their thinking about the role of labor unions in the lives of everyday Americans. In instances like these, students were thinking more deeply about the role of historical events in social movements and using details and precision to convey those ideas.

The earliest “Weekly Journal Discussion” responses also demonstrated deeper thinking and greater consciousness of other perspectives. These changes reflect the Habits of Mind of listening with understanding and empathy and thinking flexibly. Since the prompt was open-ended and students could not see other posts until they submitted their own thoughts, students used examples that resonated with them individually. Thus, students encountered one another’s perspectives on the same events they might have posted about. Or they encountered peers’ perspectives about an event they had not put as much thought into. When responding to one another, the directions on etiquette encouraged students to practice understanding and empathy, even when related to present or past experiences of people who may be vastly different than themselves. Regularly, students wrote comments like, “I hadn’t thought of it that way, but now that you’ve posted this, I’m starting to think in new ways.” This is the Habit of thinking flexibly, in which students change perspectives and consider the different options that people of the past (and perhaps now) faced in any given situation. All told, the exercise encouraged the use of detail, deeper thinking, and engagement with other perspectives as students took ownership over their own learning.

These examples suggest that retitling the assignment and presenting it as a group discussion improved student submissions. But there may be other explanations. The changes I made to the assignment directions might explain some of the increase in average word count, including my repeated directive to include specific examples and the statement that responses “must go beyond summarizing.” Additional reasons for the increased engagement might be that students felt more invested in knowing that it would be not just the instructor reading their work but also several peers. I also suspect that some online asynchronous courses have a higher percentage of self-motivated students who might enter the course with some Habits of Mind already established. Further research could determine if data support these other explanations. Even with other possible explanations for the change in student submissions, the results still demonstrate that students were developing or refining Habits of Mind like thinking about your thinking, listening with understanding and empathy, thinking flexibly, and thinking and communicating with clarity and precision. By having the assignment due weekly, students also had the opportunity to make these into true Habits of Mind through consistently repeating the exercise.

Student Perceptions

My perceptions of the assignment are just one piece of this puzzle, though. While I have seen improvement in student critical thinking and communication skills through this assignment, have the students noticed this as well? Were they seeing the transferability of these skills? Based on anonymous course evaluations, this type of discussion assignment has fostered student engagement. Some comments suggest that the increased engagement is a result of feeling listened to. In spring 2021 for HIST 2710, for instance, a student wrote, “I loved the weekly responses…it was nice to feel like my voice was [being] heard.” At least for this individual, there was a sense of other students and the instructor using the Habit of Mind of listening with understanding and empathy. A sense of being listened to may be crucial to student perceptions of their own learning. Online discussion gives everyone a voice. When framed as open-ended discussions, it also poses the potential to assist in real learning, including students who might normally feel marginalized (Lieberman, 2019).

Encountering others’ perspectives was another learning goal for me and the students, and the discussions met this objective easily. In HIST 2710 during the spring 2022 semester, for example, one student mentioned the notion of “perspective” as it related to the discussions: “I enjoyed the class discussions as well. It was great to talk to other students on what was going on in U.S. history and what our perspectives were on those events.” Similarly, a student in my fall 2022 section of HIST 1700 commented that “I also really liked that she had the assignments as discussions so we could talk to others. She had it be critical that you comment to others, so you could see their point of view. I really enjoyed that interaction.” Being able to speak up as well as hear from one another were common themes here in how students perceived their learning experience.

Other course-evaluation comments suggest that the increased engagement I observed was because students enjoyed these interactions and felt that they learned from them. This may have acted as incentive to sustain interest in discussions over the course of the semester. In course evaluations for HIST 1700 from fall 2022, one student commented, “I like how the discussions helped keep me engaged in that class and helped me retain some information by being able to read and interact with my peers.” This student perceived that they retained more information by having this open-ended kind of interaction. Another student remarked, “I thought the lectures were pretty fun and thought-provoking. I liked that it was more about what you learned in the discussions. I felt like I could be more genuine in my thinking and questions.” The level of comfort this student describes indicates a perceived sense of thinking about their own learning and how they might participate in a genuine manner. This statement also suggests a sense of increased confidence. Overall, these comments indicate that students perceived the interactions with peers as positive and instructive for both content-based knowledge and learning about other perspectives.

The course evaluation statements above were responses to end-of-semester course evaluation questions that ask students to comment on the whole course. The fact that students were choosing to include discussions at all suggests that this assignment resonates with them.

Both my perception and students’ perception of increased learning through “Weekly Journal Discussions” in online learning environments is a positive indication that this assignment develops healthy and transferable Habits of Mind. As an increasing number of students are learning online, it is crucial to find ways to engage them in not just course content but also transferable ways of thinking and learning. Students in my classes are recognizing that transferability when they describe how consistently they share ideas and information from my courses with friends and family.

Future Questions and Applications

Since most of my instruction in recent semesters has been asynchronous online, it remains to be seen how well this type of discussion assignment translates to in-person classes. I plan to use the assignment the next time I teach an in-person class, since it allows all students to have a voice in the course. Although I would continue to include in-person discussions in face-to-face courses, maintaining a weekly journal discussion as well allows everyone the chance to share their thoughts. In-person discussions might focus more closely on key concepts while allowing the online discussion board to be a more open forum.

There are several reasons that the journal discussion format might work well for in-person courses. For one, it might address the age-old problem of only some students speaking up in class unless required. When I was an undergraduate student, I lacked confidence in what I had to say, so I rarely spoke up during in-person class discussions. There are numerous other reasons students hesitate to participate in class discussions, such as individual styles or personalities and cultural values and norms (Eberly Center, n.d.-a).

While this online discussion board might not address all or even most of those reasons, it is one way to accommodate students who struggle with in-person discussion. Strategies for addressing students who are shy recommend allowing students to prepare in advance, requiring all students to participate, employing groups, and rewarding student participation (Eberly Center, n.d.-b). The journal discussion format uses all these strategies. Additionally, perhaps a validating experience in the online discussion environment would give normally taciturn students the confidence to participate during in-person discussions. Finally, students completing this kind of discussion assignment get to “own their learning” in a way that, in my experience, has often been more difficult to achieve with in-person guided discussions in introductory history courses.

Another consideration for this assignment moving forward relates to the increased presence of artificial intelligence (AI) technology, such as ChatGPT. Students might attempt to use AI technology to complete the assignment. That said, students using AI technology would have to generate their own prompts, since the prompt contains no specific details. In doing so, they are still engaged in owning their own learning. They are having to figure out how to frame a prompt to get the result they want. So, while there might be a “loss” in having the student generate their own response to the material, is there perhaps a “gain” in how they are thinking about the processes of learning by framing their own prompts to give the AI technology?

In that same vein, some instructors are suggesting that ChatGPT might be a technology to work with rather than against (D’Agostino, 2023). For instance, I might have students complete the “Weekly Journal Discussion” by creating their own prompt, submitting it to ChatGPT to generate a response, and then post the prompt they used, the resulting AI-generated response, and a short critique of the response. Students would be owning their own learning by framing prompts, and they would still be engaged in encountering other perspectives on a week’s materials. It might even open discussions about how AI constructs answers versus how humans learn. Along these lines, perhaps the assignment could require students to post their own response, then the version that they got when they used AI technology and offer some thoughts on how the two compare. Learning can still happen, though my expectations on what constitutes “learning” is likely to shift. I suppose I, too, am engaging in thinking flexibly here.

In introductory history courses, my main philosophy has been less “learn this about these specific things in the past” and more “tell me about what you’re learning.” There is, of course, value to evaluating students on specific knowledge that any given course intends to convey. In my courses, other assignments, such as written exams, achieve this. Including an assignment like the “Weekly Journal Discussion” in conjunction with assignments that evaluate specific content therefore accomplishes many possible instructional goals, whether they are content- or concept-driven.

These moments of reflection have worked well in classes regardless of modality. Many students are taking courses in multiple modalities during any given semester, so it is imperative that they understand not just what they are learning but how they learn it. This journal discussion assignment invites them into this kind of thinking and motivates them to create a habit of it.

References

Blackmon, S. (2012, July). Outcomes of chat and discussion board use in online learning: A research synthesis. Journal of Educators Online, 9(2).

Conaway, R. N., Easton, S. S., & Schmidt, W. V. (2005). Strategies for enhancing student interaction and immediacy in online courses. Business Communication Quarterly, 68(1), 23–35.

D’Agostino, S. (2023, January 12). ChatGPT advice academics can use now. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2023/01/12/academic-experts-offer-advice-chatgpt

Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence & Educational Innovation. (n.d.-a). Students don’t participate in discussion. Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/solveproblem/strat-dontparticipate/index.html

Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence & Educational Innovation. (n.d.-b). Students don’t participate in discussion: Students’ individual styles or personalities may inhibit their participation. Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/solveproblem/strat-dontparticipate/dontparticipate-03.html

Filho, W. L., Wall, T., Rayman-Bacchus, L., Mifsud, M., Pritchard, D. J., Lovren, V. O., Farinha, C., Petrovic, D. S., & Balogun, A. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 and social isolation on academic staff and students at universities: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 21(1213).

Lieberman, M. (2019, March 27). Discussion boards: Valuable? Overused? Discuss. Inside Higher Education. https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/03/27/new-approaches-discussion-boards-aim-dynamic-online-learning

Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (1988, September). Teaching for transfer. Educational Leadership, 46(1), 22–32.

Roediger, H. L. III, McDaniel, M. A., & Brown, P. C. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Belknap Press.