The Person Experiences Interview Survey: A Measure Addressing Ableism in Mental Healthcare for Patients with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

Micah Peace Urquilla

Urquilla, M. P. (2024). The Person Experiences Interview Survey: An assessment designed to address ableism in mental healthcare for patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 4(1), 1-14.

Plain Language Summary

Ableism is a kind of prejudice that impacts People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) in many parts of life, even in mental health care. Some providers may have incorrect, negative ideas about People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and Mental Healthcare (IDD-MH) experiences. In the past, providers talked to caregivers, not people with IDD-MH themselves about their healthcare needs. Caregivers’ perspectives are important, but they may be different from the person receiving services. All people with IDD-MH have a right to share their own thoughts about their mental health services. We needed an accessible tool People with IDD-MH could use to have a voice in their care. Our team included experts with and without IDD-MH to solve this problem. Using inclusive research practices, we created the Person Experiences Interview Survey (PEIS). The PEIS is adapted from another verified tool, the Family Experiences Interview Survey (FEIS.) All PEIS questions were designed to be accessible to People with IDD-MH. Both our process and the tool we created are guided by the motto, “Nothing About Us Without Us.” Experts with IDD-MH were leaders in this work from the beginning. Their input made the survey more accessible, which will ensure that more People with Disabilities are able to use it. The chance to share your experiences, and to be part of the decisions that impact your life are important to self-determination and wellbeing for everyone. Whether your voice is heard and respected can have a direct impact on one’s mental health. The PEIS can help providers and caregivers support people with IDD-MH to share thoughts about their mental healthcare. Tools like the PEIS can help People with Disabilities share their experiences and be included in choices about their treatment.

Abstract

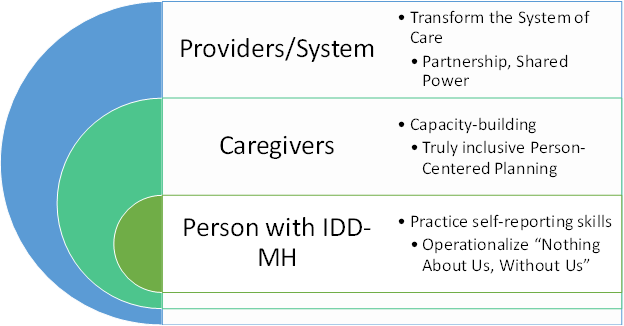

Many People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) also have mental health needs requiring the support of mental health service providers, yet they may experience barriers to full engagement in their care due to ableism. Ableism is a kind of prejudice that impacts People with IDD in many parts of life, even in mental health care. This article proposes how an adapted Patient Reported Experience Measure (PREM) can be a response to ableism, with an impact at three distinct yet interrelated levels that reflect the parties involved in the mental healthcare of People with IDD-MH: provider, caregiver, and patient.

At the provider level, implementation of the Person Experiences Interview Survey (PEIS) offers mental health providers the opportunity to engage patients as partners in their care, thus improving patient-provider rapport and communication and ultimately amounting to better services and outcomes for People with IDD-MH.

Since the PEIS engages People with IDD-MH directly, the caregiver level of impact involves an opportunity for caregivers to properly contextualize their perspectives as complementary to that of patients and further advocate for person-centered planning and the implementation of care that will honor and meet patient needs. Caregivers are invited to reframe the role they play in interactions with providers from that of sole informant and “voice of” the patient, to acting as an advocate and additional perspective supporting People with IDD-MH to engage with their providers and practice self-determination.

The central level of impact is patients—People with IDD-MH themselves. The PEIS gives People with IDD-MH the chance to practice and develop self-reporting skills, and for their insights to inform choices made regarding their care. The PEIS evaluates experiences with mental health services and providers, and the extent to which they are easy to access, appropriate, and accountable to People with IDD.

The PEIS offers all three levels the opportunity to collaborate around patient care and operationalize the Disability Rights ethos of “Nothing About Us, Without Us.”

Introduction

People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) experience a higher prevalence of mental health challenges and support needs than their nondisabled peers (Hughes-McCormack et al., 2017). (People with both IDD and mental health challenges or service experiences are for the purposes of this article referred to as People with IDD-MH.) As a result, they also spend more time interacting with mental health providers and service systems than others, often within a complex, bifurcated network of similar-yet-different service systems (Pinals et al., 2022). All people, regardless of diagnosis or Disability status, have the right to share their own thoughts about their mental health services and experiences yet no tool to facilitate dialogue promoting such feedback previously existed for People with IDD-MH (Charlton, 1998). The Person Experiences Interview Survey (PEIS) was created by a team that included experts with lived experience of IDD-MH as well as non-Disabled experts in fields related to IDD-MH. The team originally developed the PEIS as an outcome measure for the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)-funded project, Evaluation of Telehealth Services on Mental Health Outcomes for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (PI: J. Beasley). However, its potential for broader use and impact on the field emerged early in the instrument adaptation and development process and confirmed through initial cognitive interviewing and early testing, with further research in development. The following essay will provide a conceptual basis for the importance of the PEIS and the opportunity it represents for People with IDD-MH receiving services, family members and caregivers, and providers with the goal of stimulating conversation and further inquiry into the role that direct patient-provider engagement plays in service satisfaction and efficacy for People with IDD-MH and their families.

A Note on Positionality and Language

I acknowledge my positionality as someone with a Developmental Disability and lived experience in the mental healthcare system who identifies as multiply Disabled. As such, my perspectives on ableism in healthcare and power dynamics within patient-provider relationships are drawn from lived experience—both my own personal experiences, and in the stories, wisdom, culture, and mentorship shared with me by other members of the Disability community, including the three other PEIS work group members who identify as People with IDD-MH. It is in the spirit of this community and the Self-Advocacy and Disability Rights movements that I use capitalization when referring to Disability and People with Disabilities directly. My choice to capitalize these concepts, while grammatically unconventional, is a deliberate means of demonstrating alignment with the social model of Disability and recognizing Disability as a source of identity, community, culture, and shared experience. It reflects both the acknowledgment of Disability as an inherent aspect of one’s personhood and serves to acknowledge a diverse-yet-shared experience of being othered based on one’s abilities, health status, or care needs (in other words, the prevalent yet varied experience of ableism). People with Disabilities are the largest and most diverse marginalized group in our society, and that marginalization has real, tangible impacts on one’s health, wellbeing, and sense of self (World Health Organization [WHO], 2022). In recognizing these shared experiences, both of culture and marginalization, we are better positioned to address the systemic nature of the barriers explored in this work.

Ableism in Mental Health Assessment and Practices

According to Disabled attorney and activist TL Lewis, ableism is…

…a system that places value on People’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normality, intelligence, excellence, desirability, and productivity…. This system of oppression leads to people determining who is valuable and worthy based on a person’s language, appearance… [and] their ability to satisfactorily behave. (Lewis, n.d.)

Like racism, it remains a prevalent force in our society despite the social and medical progress of recent decades (Fuentes et al., 2023). Even in healthcare settings where providers frequently interact with and build therapeutic relationships with People with Disabilities, providers may hold biases—conscious or unconscious—that are not rooted in the lived experience of Disability, and are, in fact, highly ableist in nature (Kaundinya & Schroth, 2022).

Ableism usually means that when a person’s Disability is apparent, other people, out of discomfort, ignorance, and unfamiliarity, will often make negative judgments about the Disabled person’s intelligence and overall capability. This is especially true if a person cannot rely on speech to communicate, or if a person has additional intellectual Disabilities. People may take someone’s communication differences or cognitive Disabilities at face value, unfairly assuming the person cannot participate meaningfully in decisions about their own care. This always has more to do with ableism and social barriers to access and belonging than it has to do with what an individual is truly capable of. Deeply engrained ableism in mental healthcare has led to the development of practices and interventions that undermine the self-determination and advocacy of People with IDD-MH. In turn, this promotes a cycle of ableism and harms experienced by individuals as well as the systems of care they live in.

A concrete example of ableism in mental health practice is the over-utilization of proxy informants in assessment procedures. A proxy informant is a person who gives information, influenced by their own perspectives, about another person. Mental health professionals have traditionally relied on third-party perspectives on the experiences of those with IDD-MH because of the false belief that People with IDD-MH cannot provide reliable insight into their own experiences or ideas (Lee et al., 2004). These assumptions are often rooted in ableism. An example of a proxy informant is a parent or caregiver who accompanies their adult child with IDD-MH to a psychiatrist appointment. Since others, including many providers, often view the caregiver as the main spokesperson for sharing information rather than the person receiving services (hereafter referred to as patient), the psychiatrist may talk to them more than the patient during assessments. Overreliance on proxy informant feedback can hamper the process of determining the best course of treatment for a Person with IDD-MH, since it is impossible for an informant to have full insight into another person’s internal experiences. At worst, a failure to include a patient’s perspective alongside an informant’s perspective can lead to a Person with IDD-MH receiving unhelpful or even harmful treatments for months or even years. It is especially important to provide mental health services to People with IDD-MH sensitively and collaboratively because the field is still learning about what supports and services are most appropriate and meaningful for People with IDD.

Need for Accessible Mental Healthcare Assessments as a Critical Response to Ableism

There is a need for new procedures and tools in mental health care that are a critical response to ableist assumptions (Kramer et al., 2019). The PEIS was created because there was no accessible patient-reported experience measure (PREM) for People with IDD specific to mental health services.

PREMs are increasingly used to evaluate the extent to which healthcare encounters, including mental health care, include quality components. They evaluate, from the perspective of the patient, the presence of qualities determined to be essential for mental health care including the information provided, the interpersonal interaction with the provider, access to care, and being treated with respect and dignity (Fernandes et al., 2020). However, there are no known mental health PREMs designed to be accessible for People with IDD-MH. The difficulty some People with IDD-MH may experience in self-reporting is not necessarily inherent to their Disability, but rather a result of a lack of accessible information about their treatment, no accessible tools or avenues for providing feedback, and little effort on the part of the professional to engage in discussion with or provide accessible psychoeducation to People with IDD-MH (Kramer & Schwartz, 2017a).

Our team was in a unique position to develop such a tool, given its close relationship with the National Center for START Services (NCSS,) which provides evidence-based mental health and crisis intervention services to People with IDD-MH under the framework of the 3 A’s of Effective Services (Beasley, 1997). According to this framework, services must meet three standards to be effective.

- Access—Services are timely and available to those in need.

- Appropriateness—Services match individual needs and provide tools to meet those needs.

- Accountability—Services are responsive, engaging, flexible, and cost-effective for recipients.

The three A’s served as the guiding framework for the qualities of service that PEIS items assess for.

Person Experiences Interview Survey (PEIS)

The PEIS evaluates experiences with mental health services and providers and the extent to which they are easy to access, appropriate, and accountable to People with IDD. The PEIS was based on and directly adapted from the Family Experiences Interview Survey (FEIS; Tessler & Gamache, 1995), in which family members share their perspectives regarding the Person with a Disability’s mental health services and providers. The FEIS had been used within the National Center for START Services and by START providers to document outcomes and quality (Beasley et al., 2018; Kalb et al., 2019), but there was an identified need to incorporate the perspectives of People with IDD. The PEIS was developed using an iterative and collaborative process that included People with IDD and mental health service experiences, the original developer of the FEIS, and researchers with expertise in crisis prevention mental health services, accessible instrument development, and intellectual Disability (Kramer et al., 2023). After initial adaptation of the FEIS items for self-report, the PEIS workgroup, consisting of the author and three additional people who identified as People with Disabilities, reviewed the PEIS draft.

A team of experts with and without Disabilities worked together to adapt the FEIS to be accessible and relevant to People with IDD receiving mental health services themselves. This group composition and structure was intentional, designed to allow our team to operationalize the Disability community ethos of “Nothing About Us, Without Us.” Our team utilized inclusive research practices inspired by the ethos of participatory research. The choice to center the voices of People with IDD-MH can be understood as a direct response to ableist assumptions in mental health assessments. As described elsewhere (Kramer et al., 2024), the PEIS work group worked together to systematically review each original FEIS question for its accessibility and relevance to People with IDD-MH and adapt any confusing or complicated language to create a similar question for the PEIS. The work group also developed three tools to improve cognitive access and promote engagement and understanding for People with IDD-MH during their use of the PEIS. These tools include a visual response scale, an infographic explaining the different mental health providers and services assessed by the PEIS, and an instructional video to prepare respondents with IDD-MH to participate in the PEIS (Kramer et al., 2023)

Following this process, the content validity of the PEIS was examined to ensure it was easy to understand, comprehensive, and relevant to the experiences of People with IDD receiving mental health services (Kramer et al., 2023). As reported elsewhere, in cognitive interviews with nine People with IDD and mental health service experiences (ages 23-49), 15 of the 21 items evaluated had 80% or greater comprehension (Kramer et al., 2023). In addition, People with IDD were able to use the response scale effectively to differentiate between positive and negative experiences. All items were rated as important by People with IDD. The cognitive interviews with People with IDD were complemented by focus groups with family caregivers and mental health providers (Kramer et al., 2023). They reviewed the draft PEIS items, and 94% of family caregivers and 88% of providers rated the PEIS items as important. As a result of this evaluation process, the PEIS was revised to enhance comprehension and reduce the total number of questions. The PEIS includes 17 items, 3 of which are open-ended questions. The remaining questions are answered using a 4-point response scale: “All that I want or need,” “Some, but not as much as I want or need,” “Very little,” and “Not at all.” The response scale includes a visual support that uses colors and symbols to help People with IDD differentiate between categories.

Proposed Impact of the PEIS on Providers, Caregivers, and People with IDD

While the PEIS was designed specifically by and for People with IDD-MH, they are not the only population who stands to benefit from implementing the PEIS as a regular part of mental health assessment procedures. The PEIS provides opportunities to those who are engaged with the mental health service system at three integral levels: (1) service providers, (2) the caregiver and family system, and (3) the individual with IDD-MH (see Figure 1).

Framework of Interconnected Opportunities for Promoting Self-Determination Through the PEIS.

Provider Impact

The first level of impact involves providers. The PEIS presents providers with an opportunity to engage the patient as a partner in their treatment, rather than a mere object of that treatment. The benefits of this partnership mean the provision of mental health services that are appropriate and meet the need of People with IDD.

Power and Partnership

A power differential exists in all healthcare relationships. The nature and impact of these differentials is influenced by a variety of factors including unconscious bias and stereotyping, limited health literacy, and cross-cultural communication challenges (White & Stubblefield-Tave, 2017). As the figure of authority between a service and the people who need it, providers hold a lot of power in shaping the nature of the service system and how it is experienced by those within it (Chicoine et al., 2022). This power differential is compounded for People with IDD-MH, because of the influence ableism has on many healthcare interactions (Roscigno, 2013). When a person has significant communication needs and/or intellectual disabilities, mental healthcare providers may overlook strengths or stressors in a person’s life or misattribute emotional or even physical distress to their IDD because of implicit biases about Disability. The result is that providers must make their best guess, and without critical information from the patient’s life, these guesses may fall short of meeting a patient’s needs and thwart opportunities for self-advocacy on the part of the patient. Even well-intentioned providers can unintentionally disempower their patients with IDD-MH by maintaining relatively surface-level interactions wherein they view themselves as the expert and the Person with IDD-MH as the recipient of that expertise, rather than as an active agent with expertise in their own lived experience and a vested interest in their treatment and its success (Joshi & Pappageorge, 2023). White and Stubblefield-Tave advise providers that…

…while clinicians have the privileges and responsibilities of professionalism…the patient has his or her own moral, ethical, and legal right to expect compassionate care that is not compromised, consciously or unconsciously, by harmful human biases on the part of the clinician. (White & Stubblefield-Tave, 2017, p. 474)

Thus, the provider-patient relationship should be viewed as one of partnership, wherein both parties have expertise and information that is vital to the success of the therapeutic relationship and the individual’s overall outcomes (Jacob, 2014). In asking the patient’s honest opinion, the provider invites the patient to shift from a passive recipient of treatment to an active participant and partner in that treatment. The PEIS provides an opportunity for the provider to operationalize shared power. Giving People with IDD-MH an opportunity to share their treatment experiences and ideas about their needs means acknowledging and respecting individual autonomy and creating opportunities to practice self-determination.

Better Mental Health Services for People with IDD

When the PEIS is administered respectfully and with proper supports, it can enhance the sense of trust and rapport that the individual with IDD-MH feels toward their provider, instilling a sense that the provider sees them for who they are, not just their disabilities (The Joint Commission, Division of Healthcare Improvement, 2016). This sense of rapport and partnership with one’s providers is critical for remaining engaged with one’s treatment over time and is associated with positive outcomes (Bigby & Beadle-Brown, 2018)

Without recognizing the value of the direct perspectives of People with IDD, providers deliver services that are based on their own ideas of Disability and modalities learned, and not the person’s individualized needs. A provider can use the PEIS to obtain information they would not have had perspective on otherwise, insights that can remove some of the guesswork from the treatment process. The PEIS creates an opportunity for providers to leverage their expertise in clinical interviewing to facilitate the voice of patients. Asking People with IDD-MH for their direct, personal feedback enables them to provide vital information on how they are experiencing their treatment—what they view as helpful, harmful, or perhaps missing altogether in their care—that no provider or proxy informant could have discerned on their own, or at best could only have done so over the course of many months and failed trials.

Success in mental healthcare is sometimes judged in terms of compliance, or how closely a person follows a prescribed treatment plan. While important, compliance is only one factor in successful mental healthcare, and a person’s compliance with their plan of care can be impacted by a wide range of other factors, including that person’s sense of whether that prescribed treatment plan will meet their needs. Similarly, when People with IDD-MH face barriers to success in their mental health treatment, their lack of success is often attributed directly to their Disabilities, leaving other potential factors, like whether the provider or treatment is a good fit, overlooked and unexplored. For this reason, the PEIS includes several items for evaluating a Person with IDD-MH’s perceived overall quality of services and interactions with providers. PEIS item #14 asks, “How often were you satisfied with your mental health services?” Patient responses, from “All that I want or need” to “Not at all,” can help the provider understand where barriers and gaps in care are preventing a Person with IDD-MH from benefiting from their services and adjust treatment plans accordingly. The information gleaned through PEIS interviews is not intended to be simply documented and filed away; it is intended to help directly inform and shape future decisions in an individual’s care. To this end, the PEIS is maximized through repeated assessments that allow for comparison over time to see if perceptions of mental health services are improving.

Considering ethical dimensions of ableism within healthcare relationships as examined here, an important consideration for every PEIS administered is the process of ensuring understanding and consent of the patient themselves, in addition to that of any caregivers, guardians, or other proxy informants present. During the development of the PEIS, the work group repeatedly stressed the importance of trust when sharing personal experiences, and the role that the respectful and equitable sharing of information plays in establishing trust with providers. The PEIS cannot be appropriately or accurately administered without a shared understanding of what the PEIS process consists of and how the information a patient shares will be used. The PEIS administration manual includes this imperative. The PEIS work group created two tools for People with IDD-MH to aid in assuring understanding and informed consent prior to completing the PEIS: a plain language video about completing the PEIS with a provider, and a visual aid that gives examples of the kinds of mental health services and providers People with IDD-MH may have worked with to reflect on while completing the PEIS.

Caregiver Impact

The second level of impact involves caregivers, who are often involved in People with IDD-MH’s mental healthcare and support services. Family members and caregivers are in a unique position to advocate for person-centered planning in their loved one’s care, and indeed to support People with IDD to develop their own advocacy skills as a part of that process. Their capacity to do so can be supported using tools such as the PEIS.

Advocate for Person-Centered Planning

Person-centered planning is an evidence-based best practice for coordinating supports for People with IDD. Most person-centered planning processes include considering the supports and accommodations a person needs in the context of their entire family system, ideally including the perspectives of both Persons with IDD as well as their family. Families and caregivers play an important role in the lives of People with IDD by acting as care coordinators, advocating for respectful treatment and reduced diagnostic overshadowing, and rallying around gaps in care and systemic shortcomings (Holingue et al., 2020; İsvan et al., 2023; Weiss et al., 2009). While their critical role in supporting the wellbeing of People with IDD-MH cannot be understated, even caregivers with the best intentions may unintentionally interfere with the “person” the planning is intended for if opportunities are not provided to truly include People with IDD-MH through direct engagement and opportunities for self-determination. Advocating for someone is not the same as speaking for someone, yet many caregivers may erroneously believe that they must “be the voice” for those in their care (Wong, 2023). Although well-intentioned, privileging a caregiver’s perspective over that of the Person with IDD-MH receiving services can inadvertently thwart opportunities for the individual to develop rapport with their provider and practice important skills to be discussed in the next section. The PEIS presents the opportunity for caregiver perspectives to be properly contextualized as complementary to a Person with IDD-MH’s own views, giving healthcare providers a more complete picture of a person’s needs and experiences than only one party’s feedback would have allowed.

Reimagining Caregiver Involvement in Services

Given the vital nature of family support in one’s mental health treatment, the PEIS contains an item to assess satisfaction with the level of family involvement in a person’s treatment. PEIS item #8 asks, “How often were you satisfied with your family member’s involvement in your treatment? If you don’t have a family member involved, you can think about a friend or other support person who is involved in your treatment.” This allows providers to determine not only if a Person has family support for their care, but if the person is happy with how their family has been involved in their care.

An important theme that emerged in the PEIS work group’s discussions around adapting this item is that while caregiver perspectives are important, they are different from the views of People with IDD-MH in ways that can impact the quality of care. The majority of the PEIS work group members with IDD-MH, the author included, could recount an experience where they felt silenced or ignored because the provider spoke to the caregiver more than the patient themselves. People with IDD-MH may want their caregivers involved in certain aspects of their treatment but want more privacy and direct engagement with their providers in other aspects. Some People with IDD-MH may not have family who are willing or able to be involved, but may have other trusted supporters, like close friends or support staff, that they wish could be more involved in their care. One PEIS work group member noted that growing up in state-provided care, she wanted support for appointments but would have liked more choice in who supported her during appointments with clinicians. For these and other reasons, it was necessary to ensure that the item assessed not only that a caregiver was involved with treatment, but that they were involved in ways that the Person with IDD-MH found satisfying and helpful.

Impact on the Person with IDD-MH

The third level of impact, at the heart of it all, involves the Person with IDD-MH. Using the PEIS, patients with IDD-MH can develop self-reporting skills and act in a self-determined manner.

Developing Self-Report Skills

As discussed at the caregiver level, one challenge to self-reporting and self-determination in mental health services is the ableist assumption that People with IDD-MH’s impairments render them unable to share ideas or opinions about their experiences. It is likely that some People with IDD-MH may give unexpected, unintended, or unrelated responses to the PEIS. These responses should not be misunderstood as an indicator of a total inability to self-report, but rather understood as the earliest stages of a Person with IDD-MH finding their voice and comfort sharing their own ideas in the form of a self-report survey, which is the necessary foundation for building the skills required to self-report. Completing a self-report, such as the PEIS, requires a set of skills (Kramer & Schwartz, 2017). First, the individual must reflect on their experiences and decide what is important to share. Second, the individual must translate that reflection to their needs, and evaluate choices based on that reflection. Third, the person must speak up for their needs, and figure out who can help them meet those needs. Non-disabled children have many, varied natural opportunities to practice and develop these skills throughout daily life, but for People with Disabilities, particularly those with significant intellectual or communication-related disabilities, these opportunities must be pro-actively created and encouraged (Williams, 2023). When they are not, a self-perpetuating cycle is created, wherein People with IDD-MH are denied the opportunity to self-report due to perceived lack of ability, yet they are never afforded the opportunity to develop the skill, similarly out of perceived lack of ability. The PEIS creates an opportunity not only for People with IDD-MH to practice these skills, but for the input they give to inform their treatment and outcomes as well, paving the way for more self-determined services and supports.

Act in a Self-Determined Manner

The self-advocacy slogan and organizing principle, “Nothing About Us Without Us” was first used amongst Disability Rights activists in the early 1990s to describe the most central tenet of the movement: in the words of late Disability Rights leader Ed Roberts, “When you let others speak for you, you lose” (Charlton, 1998). By creating an avenue for a People with IDD-MH to be directly engaged and self-determining in their mental health services, the PEIS emphasizes to the individual that they are receiving services for their own benefit, not because others are bothered with them or wish to punish or control them.

Several PEIS items directly assess a person’s input and control in their own treatment. An example of these is item #7 which asks, “How often did mental health providers give you a chance to make decisions about your treatment?” This survey item is intended to provide insight into a patient’s sense of autonomy as it relates to their mental healthcare, and this information can support a provider in reflecting on how they can share power to encourage People with IDD-MH in their care to become more directly engaged in their treatment decisions, what barriers may be preventing them from making their own choices, and what supports are needed to promote self-determination.

Moving Forward

The PEIS is a path forward to address ableism in mental healthcare and may benefit People with IDD, family caregivers, and providers. The PEIS provides a means to assess Person-centered mental health services and adjust supports accordingly. Over time, with repeated use and careful implementation, the PEIS can help providers determine and assess trends in a patient’s treatments and experiences and address persistent trends and needs by factoring patient feedback into future decisions regarding care. This is a shift that has the potential to transform not only the quality of an individual’s mental health care and the patient-provider relationship, but the dynamics within a person’s broader system of care, although care must be taken on the part of the provider and PEIS administrator to be mindful of the implicit value judgments that can accompany ableist bias. Such value judgments may cause providers to overlook important patient concerns or needs, or discount information shared in PEIS responses because it judged to be of inferior quality or relevance (Lewis, n.d.; White & Stubblefield-Tave, 2017). Each PEIS interview ends with three open-ended questions, including item #15, “Do you think mental health providers and services pay attention to the needs of People with Disabilities?” It may be an uncomfortable question for providers to confront, but openly and critically engaging with patients on the subject is a necessary step toward transforming ableism and imbalanced power dynamics into a therapeutic relationship based on respect and partnership. A patient’s responses to the PEIS are likely to point providers towards strategies they can employ to critically engage with ableist biases within the field and ensure that they are providing accessible services and compassionate, truly person-centered care.

References

Beasley, J. (1997). The three A’s in policy development to promote effective mental healthcare for people with developmental disabilities. The Habilitative Mental Healthcare Newsletter, 16(2), 31-33.

Beasley, J., Kalb, L. G., & Klein, A. (2018). Improving mental health outcomes for individuals with intellectual disability through the Iowa START (I-START) program. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 11(4), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864. 2018.1504362

Bigby, C., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2018). Improving quality of life outcomes in supported accommodation for people with intellectual disability: What makes a difference? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(2), e182–e200. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12291

Charlton, J. I. (1998). Nothing about us without Us: Disability oppression and empowerment. University of California Press.

Chicoine, C., Hickey, E. E., Kirschner, K. L., & Chicoine, B. A. (2022). Ableism at the bedside: People with intellectual disabilities and COVID-19. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 35(2), 390–393.

Fernandes, S., Fond, G., Zendjidjian, X. Y., Baumstarck, K., Lançon, C., Berna, F., Schurhoff, F., Aouizerate, B., Henry, C., Etain, B., Samalin, L., Leboyer, M., Llorca, P.-M., Coldefy, M., Auquier, P., & Boyer, L. (2020). Measuring the patient experience of mental health care: A systematic and critical review of patient-reported experience measures. Patient Preference and Adherence, 14, 2147–2161. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S255264

Fuentes, K., Hsu, S., Patel, S., & Lindsay, S. (2023). More than just double discrimination: A scoping review of the experiences and impact of ableism and racism in employment. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2023.2173315

Holingue, C., Kalb, L. G., Klein, A., & Beasley, J. B. (2020). Experiences with the mental health service system of family caregivers of individuals with an intellectual/developmental disability referred to START. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 58(5), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-58.5.379

Hughes-McCormack, L. A., Rydzewska, E., Henderson, A., MacIntyre, C., Rintoul, J., & Cooper, S.-A. (2017). Prevalence of mental health conditions and relationship with general health in a whole-country population of people with intellectual disabilities compared with the general population. BJPsych Open, 3(5), 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjpo.bp.117.005462

İsvan, N., Bonardi, A., & Hiersteiner, D. (2023). Effects of person-centered planning and practices on the health and well-being of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A multilevel analysis of linked administrative and survey data. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 67(12), 1249–1269. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.13015

Jacob, K. S. (2014). DSM-5 and culture: The need to move towards a shared model of care within a more equal patient–physician partnership. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 7, 89–91. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.11.012

Joint Commission, Division of Healthcare Improvement. (2016). Implicit bias in health care. Quick Safety, 23. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/newsletters/newsletters /quick-safety/quick-safety-issue-23-implicit-bias-in-health-care/implicit-bias-in-health-care/

Joshi, P., & Pappageorge, J. (2023). Reimagining disability: A call to action. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 3(2). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/ddnj/vol3/iss2/7

Kalb, L. G., Beasley, J. B., Caoili, A., & Klein, A. (2019). Improvement in mental health outcomes and caregiver service experiences associated with the START program. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 124(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-124.1.25

Kaundinya, T., & Schroth, S. (2022). Dismantle ableism, accept disability: Making the case for anti-ableism in medical education. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 9. https://doi.org/10.1177/23821205221076660

Kramer, J. M., Beasley, J. B., Caoili, A., Kalb, L., Peace Urquilla, M., Klein, A., Poncelet, J., Black, S., & Tessler, R. (2023). Development and content validity of The Person Experiences Interview Survey (PEIS): A measure of the mental health services experiences of people with developmental disabilities. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1271210

Kramer, J. M., Dean, E. V., Peace Urquilla, M., Beasley, J. B., & Linnenkamp, B. (2024). Collaboration with researchers with intellectual/developmental disabilities: An illustration of inclusive research attributes across two projects. Inclusion, 12(1), 55–74.

Kramer, J. M., & Schwartz, A. (2017a). Reducing barriers to patient-reported outcome measures for people with cognitive impairments. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 98(8), 1705–1715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.03.011

Kramer, J. M., Schwartz, A. E., Watkins, D., Peace, M., Luterman, S., Barnhart, B., Bouma-Sims, J., Riley, J., Shouse, J., Maharaj, R., Rosenberg, C. R., Harvey, K., Huereña, J., Schmid, K., & Alexander, J. S. (2019). Improving research and practice: Priorities for young adults with intellectual/ developmental disabilities and mental health needs. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 12(3–4), 97–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2019.1636910

Lee, S., Mathiowetz, N. A., & Tourangeau, R. (2004). Perceptions of disability: The effect of self- and proxy response. Journal of Official Statistics, 20(4), 671–686.

Lewis, T. A. (n.d.). Working definition of ableism—January 2022 Update. http://www.talilalewis.com/ 1/post/2022/01/working-definition-of-ableism-january-2022-update.html

Pinals, D. A., Hovermale, L., Mauch, D., & Anacker, L. (2022). Persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the mental health system: Part 1. Clinical considerations. Psychiatric Services, 73(3), 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900504

Roscigno, C. I. (2013). Challenging nurses’ cultural competence of disability to improve interpersonal interactions. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing: Journal of the American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, 45(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0b013e318275b23b

Tessler, R., & Gamache, G. (1995). Toolkit for evaluating family experiences with severe mental illness. Sociology Department Reports and Working Papers. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/sociol_ reports/1

Weiss, J. A., Lunsky, Y., Gracey, C., Canrinus, M., & Morris, S. (2009). Emergency psychiatric services for individuals with intellectual disabilities: Caregivers’ perspectives. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22(4), 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00468.x

White, A. A., & Stubblefield-Tave, B. (2017). Some advice for physicians and other clinicians treating minorities, women, and other patients at risk of receiving health care disparities. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 4(3), 472–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0248-6

Williams, B. (2023, August 29). Unjustly isolated, silenced, and deprived of literacy and freedom of expression. CommunicationFIRST. https://communicationfirst.org/unjustly-isolated-silenced-and-deprived-of-literacy-and-freedom-of-expression/

Wong, A. (2023, February 28). I still have a voice. KQED. https://www.kqed.org/perspectives/201601 142614/alice-wong-i-still-have-a-voice

World Health Organization. (2022). Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240063600