Project ATTAIN: Advancing Trauma-Informed Care for Youth with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and/or Gender-Diverse Youth

Kady F. Sternberg; Charlotte E. Bausha; Charlotte Jones; Erin Knight; Crystal N. Steltenpohl; Rebecca Parton; Jennifer L. McLaren; and Erin Barnett

Sternberg, K. F., Bausha, C. B., Jones, C., Knight, E., Steltenpohl, C. N., Parton, R., McLaren, J. L., & Barnett, E. (2024). Project ATTAIN: Advancing trauma-informed care for youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities and/or gender-diverse youth. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 4(1), 57-79.

Plain Language Summary

Children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) and/or gender diversity are at risk of experiencing scary or frightening events. Finding a treatment that can help with stress or trauma and support gender diversity or IDD can be hard. Our program, called Project ATTAIN, aims to teach providers to help children and families living with stress or trauma, IDD, and/or gender diversity.

We have psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, direct care staff, and people with lived experience on our project team. We also have an advisory board that includes service providers, people with lived experience, and guardians. ATTAIN wants to provide trauma‑, disability-, and LGBTQ+-informed training to people who work with people with IDD and/ or gender diversity. We want doctors to ask about trauma and quality of life more often. We want to include IDD and gender-diverse people in our work.

We surveyed 39 people who work with people with IDD and/or gender diversity. We asked them about their knowledge of trauma-, disability-, and LGBTQ+-informed practices. We trained 966 people in trauma-informed care practices. We screened 49 people within our IDD services for trauma. Our project included two people with lived research experience. We found that people who work with IDD and/or gender-diverse youth need training to help expand the practices they use at their jobs. We will continue to track our work on outreach, training, and screening efforts as the program continues.

Abstract

Children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) and/or gender diversity are at higher risk of experiencing trauma. Provider knowledge is lacking; trauma, disability, and LGBTQ+ resources are often siloed; and few providers screen for trauma in this population. This paper describes the design, delivery, and initial evaluation of Project ATTAIN (Access to Trauma-informed Treatment and Assessment for Neurodivergent and/or Gender-Expansive Youth).

ATTAIN is an ongoing 5-year, state-wide initiative aiming to assess readiness to engage in new roles and practices over time; provide state-wide training and consultation in trauma‑, disability-, and LGBTQ+-informed practices; install screening and assessment of trauma exposure, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and quality of life into IDD and gender service settings; and include people with lived experience. A readiness assessment identified pre-training gaps between role responsibilities and practice engagement across five professional sectors serving our target population (n = 39) in LGBTQ+-, disability-, and trauma-informed practices. We learned that specific sectors would benefit from introductory training to increase buy-in and promote role expansion; others would benefit from advanced instruction and implementation support. So far, we have trained 966 unique providers in trauma-informed care and have seen changes in the attitudes or perspectives of participants. Participants were highly satisfied with our provided training and saw increased knowledge across training. We screened 49 people in an IDD service setting for PTSD and quality of life. Two people with lived experience are active members of our research team, participating in project planning, training delivery, and manuscript authorship.

Individuals who work with IDD and/or gender-diverse youth would benefit from increased training to expand their knowledge on LGBTQ+-, disability-, and trauma-informed practices. In year 3, we intend to continue outreach and evidence-informed training focused on the intersection of trauma, IDD, and gender diversity. Ongoing evaluation of our outreach, training, and screening efforts will continue to inform program activities.

Introduction

Project ATTAIN (Access to Trauma-informed Treatment and Assessment for Neurodivergent and/or Gender-expansive Youth) is a 5-year, state-wide program funded by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. The program aims to assess provider readiness to use and their knowledge of trauma-informed, gender-informed, and disability-informed practices through training, screening, and implementation of evidence-based treatment across the state of New Hampshire (NH) for youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD; i.e. autism, intellectual disability) and/or gender-diverse youth aged 0-25 years and their families. Our program focuses broadly on neurodivergence but in this paper we will focus primarily on autistic youth and youth with intellectual disabilities. This paper describes, analyzes, and synthesizes the first 2 years of activities related to four of the primary goals of Project ATTAIN: (1) understand workforce readiness, (2) improve provider knowledge and practice through our workforce training program, (3) implement screening, and (4) meaningfully include individuals with lived experience.

Children and young adults with IDD are at higher risk than those without IDD of experiencing trauma such as victimization (Brendli et al., 2022; Jones et al., 2012), sexual abuse (Hershkowitz et al., 2007; Mandell et al., 2005), and maltreatment (MacLean et al., 2017; McDonnell et al., 2019), as well as peer rejection (Son et al., 2012) and instances of seclusion and restraint (O’Donoghue et al., 2020). Despite the high prevalence of traumatic events experienced by people with IDD, traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are rarely assessed and often go unrecognized (Kildahl et al., 2020; Mevissen & de Jongh, 2010). Discerning physical or emotional changes due to trauma are often attributed to behavioral issues rather than the underlying experience of trauma (Baladerian, n.d.; Kerns et al., 2023). Further, few providers or organizations screen for trauma and other stressors in this population (National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2020b). When issues related to trauma and stress are recognized, people often do not receive quality care. For example, Berg et al. (2018) found that only 32% of autistic children—autism is one type of IDD—and their families reported receiving effective care coordination. For the purposes of this paper, we will be using identity-first language to describe autistic individuals, in accordance with many autistic self-advocates’ expressed preferences (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2021; Taboas et al., 2023).

Fortunately, an emerging body of evidence has also documented the role of positive childhood experiences as drivers of resilience and quality of life in youth, demonstrating the incredible strengths of people with IDD to overcome hardship. Research indicates that these positive experiences may minimize adult mental and relational health issues, increase resilience, and promote flourishing in youth with IDD (Bethell et al., 2019; Crouch et al., 2023; Han et al., 2023). However, like trauma screeners, measuring positive experiences or quality of life is rare in people with IDD (Burgess & Gustein, 2007; Ijezie et al., 2023).

Gender diversity is an overarching term referring to the extent to which an individual’s gender expression or identity may vary from social expectations of binary gender assigned at birth (American Psychological Association [APA] Division 16 & 44, 2015; Coleman et al., 2022). In the context of this paper, we are focused mainly on transgender and gender nonconforming individuals, who we will refer to as gender-diverse. Transgender describes when an individual’s gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth (male or female; APA Division 16 & 44, 2015). Gender nonconformity describes when an individual’s gender expression, role, or identity falls outside societal expectations based on the gender they were assigned at birth (APA Division 16 & 44, 2015; Coleman et al., 2022).

Like individuals with IDD, many studies have documented higher rates of trauma (e.g., assault) and minority-related stressors in gender-diverse people compared to their cisgender counterparts (Aparicio-Garcia et al., 2018; Johns et al., 2019; Price et al., 2023; Schnarrs et al., 2019). For example, transgender individuals are more likely to experience minority stressors such as housing discrimination, verbal harassment in public spaces, harassment by law enforcement, and are less likely to receive quality healthcare than cisgender individuals (Grant et al., 2011). Gender-diverse people’s increased risk of experiencing traumatic events and minority stressors increases their risk of developing mental health symptoms and conditions, including PTSD symptoms (Reisner et al., 2016; Soloman et al., 2021).

Again, positive childhood experiences, including having safe and supportive family and friends, can buffer against these stressors and traumas in all youth (Bethell et al., 2019; Crouch et al., 2023; Han et al., 2023). Gender-affirming care is an additional buffer, which can help improve mental and physical health outcomes for gender-diverse individuals (Olson et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2018). Providers are not always well educated on the issues faced by transgender populations. Youth do not always receive confidential care, and they may be treated by providers who are uncomfortable with their gender identity and by providers who do not use their proper name or pronouns (Canvin et al., 2022; Pampati et al., 2021; Reisner et al., 2022). Barriers such as these can prevent people from seeking and receiving quality care.

Emerging research has shown gender diversity and autism co-occur at higher rates than in the general population (de Vries et al., 2010; Kallitsounaki & Williams, 2022; Strang et al., 2016). Warrier et al. (2020) found transgender and gender-nonconforming people were 3-6 times more likely to be autistic than those identifying as cisgender. Similarly, a 2019 study found that autistic children are four times more likely to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria compared to children without autism (Hisle-Gorman et al., 2019). Given that both populations, separately, are vulnerable to trauma, there may be unique needs for people living at the “triple intersection” of autism, gender diversity, and trauma.

People who are gender-diverse and have IDD also possess a range of strengths and sources of resilience that stem from their unique experiences and perspectives. For example, a notable proportion of gender-diverse individuals engage in activism and advocacy despite adversity and victimization, showing their resilience and determination to challenge societal norms and injustices (Trinh et al., 2022). Among gender-diverse individuals, positive social support from friends and family, other gender-diverse individuals, and healthcare providers, like therapists, can positively impact their resilience (Gorman et al., 2022). For the IDD community, people find resilience in various ways, including acceptance, autonomy, perseverance, and positive experiences through supportive social networks and healthcare systems (Scheffers et al., 2023).

Project ATTAIN seeks to develop gender-affirming, disability-informed, and trauma-informed care that enhances the well-being of individuals with gender-diverse identities and/or IDD. Making these changes involves increasing training and education within care sectors, formulating innovative solutions, and implementing screeners to better assess and meet the unique needs of these populations. Integral to the research approach is proactive consultation and inclusion of people with lived experience, ensuring their valuable insights are not only acknowledged, but actively incorporated into the process of developing and refining these care solutions. Lived-experience perspectives are essential to making positive and impactful changes in inclusive care practices.

Methods

In this paper, we report on four goals from Project ATTAIN: (1) to gauge interest in and use of trauma-informed, disability-informed, and LBTQ+-informed practices in multiple care sectors through a state-wide readiness assessment; (2) provide state-wide trauma, disability, and LGBTQ+-informed training and consultation to a multidisciplinary workforce, (3) increase screening and assessment for trauma and quality of life within clinics serving youth with IDD and/or gender diversity in our medical center, and (4) include people with lived experience in guiding project goals, co-training, and co-authoring. In this section, we describe the Project activities associated with each goal, followed by evaluation methods, data collection, and analytic strategies when relevant.

Goal 1 – Readiness Assessment

Before implementing training, we surveyed care professionals throughout New Hampshire to gauge interest and readiness for trauma-informed, disability-informed, and LGBTQ+-informed training and practices. We developed the readiness assessment survey using modified items from an existing, validated measure, the Implementation Leadership Scale (ILS) (Aarons et al., 2014), as well as developed items based on an informed literature review (Fernandez et al., 2018). The survey included 66 Likert scale items, four “select all that apply” items, and eight demographic items. The survey asked about their organization’s perceived role (role) in and the use of (engagement) trauma-informed, LGBTQ+-informed, and disability-informed practices while serving families and youth within their organization. For example, “To what extent do you view the following practices as part of your organization’s role in serving youth and families?” (role), and “How often do your teams/staff engage in the following practices?” (engagement). We also assessed barriers to implementing practices (e.g., budget, training), knowledge of evidence-based practices, and interest in training.

We distributed online surveys using Qualtrics via email between April and June 2022 (Qualtrics, 2020). We surveyed director-level individuals working within five care sectors throughout ten state regions. Care sectors included Applied Behavior Analysis services (ABA), developmental disability services, mental health services, pediatric practices, and schools. We used descriptive statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation, frequencies) and Spearman’s correlation coefficient to analyze results. We identified congruence between engagement and role using correlations. Strong congruence (r > 0.66) meant sector responses in role and engagement were highly positively correlated (e.g., saw it as their role and engaged in the practice). Moderate congruence was defined as 0.33 ≤ r ≤ 0.66, and weak congruence was defined as 0 < r < 0.33. Strong incongruence (r < -0.66) meant sector responses in role and engagement were negatively correlated (e.g., saw it as their role but did not engage in practice). Moderate incongruence was defined as -0.33 ≥ r ≥ -0.66, and weak incongruence was defined as 0 ≥ r ≥ -0.33. Findings informed training content and targeted audience.

Goal 2 – Trauma, LGBTQ+, and Disability-Informed Training to Multiple Care Sectors

Triple Intersection Training

ATTAIN provided statewide training on trauma, disability, and LGBTQ+-informed practices and consultation to a multidisciplinary workforce. Experts in the field and a partner with lived experience developed the training and co-presented them. Topics included the intersection of gender diversity and trauma, IDD and trauma, and the triple intersection of IDD, trauma, and gender diversity. All the trainings had a core foundation of trauma-informed practices. In the first 2 years of the project, we delivered an online four-part series focused on the triple intersection twice. Additionally, we delivered shorter versions of the triple intersection curriculum to various audiences, both in person and online. Two trainings on trauma and IDD were made into enduring materials for continuing education credits. Participants were employed across mental health, intellectual or developmental disability service agencies, child welfare, and schools.

During the four-part series, we administered an online survey through an institution-hosted REDCap (Harris et al., 2009) during the last 15 minutes of each session to gather training feedback and outcomes. The survey assessed participant demographics (e.g., role, sector, gender), training processes (e.g., quantity of information presented, length of and timing between sessions), and outcomes (e.g., trauma-informed practices), primarily through Likert-type items. We included researcher-developed items and items from existing, validated measures (Barnett et al., 2018; Little et al., 2020; Meyer et al., 2013). Outcomes were assessed after individual sessions and at the conclusion of the series (after all four sessions).

Series outcomes were examined using a retrospective pre/post format, in which participants were asked the same question twice within one survey, once reflecting on their current knowledge and skills and once on their knowledge and skills before the session or series (Little et al., 2020). This format allows for pre/post items to be included on one survey instrument and addresses potential response shift bias (Meyer et al., 2013). Specifically, outcomes related to whether training increased participants’ knowledge and skills were assessed using items from the Trauma-Informed Self-Assessment (TISA; Barnett et al., 2018). We also examined activities related to the training that they believed they would do (after the first session) and have done (after the last session) because of the training (e.g., looking up other organizations in their area).

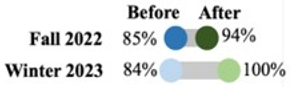

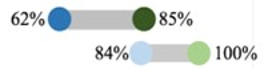

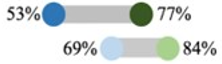

Finally, we assessed whether there was a change in participants’ practices (e.g., considered trauma in their work with youth). Most items employed response formats that were Likert scale or “select all that apply.” We assessed increases in knowledge, activities, and participant practices by comparing the percent of participants who agree or strongly agree on TISA items, before and after the trainings, for the fall 2022 and winter 2023 series (see Figure 3, later in this manuscript).

CARE Training

With the oversight of its original creators, we provided CARE (Caregiver Adult Relationship Enhancement) Connections training. CARE Connections is an evidence-informed single-session training that provides adult participants with trauma-informed behavioral skills for working with children/teens who have experienced trauma (Gurwitch et al., 2016; NCTSN, 2020a), adapted for an IDD population. We provided CARE training in person to residential treatment providers throughout the state.

We distributed paper surveys at the end of the training. The survey was created by CARE training developers and consisted of 13 Likert scale items (strongly disagree to strongly agree) assessing skills learned, confidence in implementing the skills, and satisfaction with the training. The survey included three open-ended items and six demographic items (gender, role/sector, neurodivergent status). We analyzed data from the 52 CARE surveys using descriptive statistics.

Goal 3 – Screening and Assessment

We implemented the CATS-2 (Child Adolescent Trauma Screener – version 2; Sachser et al., 2022) for all youth within our autism and neurodevelopmental clinics in the psychiatry department at a large medical center serving northern New England. We also used two short-form self-report and parent proxy PROMIS Quality of Life measures, V1.0-life satisfaction SF 4a and V1.0-meaning and purpose SF 4a (Graham Holmes et al., 2020). These measures were used for all behavioral and neurodevelopmental evaluations and services at our medical center. Further, our medical center, through a different initiative, introduced a gender identity item to the online medical record that people 18+ can complete or change. Parents with children younger than 18 can request that their provider change the gender identity of their child in the online medical record.

Our team will regularly gather the number of completed screens and results of the trauma, quality of life, and gender items for further research.

Goal 4 – Inclusion of People with Lived Experience

Within the first year of the project, we recognized the importance of genuine partnership and contributions from people with lived experience. We co-developed the curriculum and have since regularly co-trained with an individual with lived expertise. They are an integral member of our team and contribute to decision making for the overall project. In addition, the Project ATTAIN advisory board consists of staff from multiple sectors, including developmental disability services, Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), schools, the Department of Education, mental health, higher education, pediatrics, and professionals with lived experience. We also have a parent and a young adult with lived experience on our board. The parent represents a parent network for youth with disabilities. Through our quarterly advisory board meetings, we build connections with other statewide groups (e.g., LGBTQ+ advocacy groups), include diverse perspectives and priorities in our trainings and activities, and disseminate information about our project and opportunities statewide. We are partnering with additional people with lived experience on more specific parts of the project as it develops.

Results

Goal 1 – Statewide Readiness Assessment

The sample encompassed agency leaders and supervisors within the sectors of ABA, developmental disability, mental health, pediatrics, and schools and represented all 10 NH counties. Thirty-nine out of 162 who were invited to complete the survey had valid survey responses. Each sector saw four to five participants except for ABA, which only had two. Because of this, we were unable to draw findings about the ABA sector. Participants were, on average, 48 years old, with an age range spanning from 31 to 67 years. Most (80%) of the participants held a master’s degree. On average, these individuals had accumulated 22 years of professional experience in their respective fields and a decade of tenure in their current employment positions. Most (94%) of the participants identified as female, the remaining 6% identified as male, and no participants identified as transgender and/or non-binary. Additionally, 93% of the participants self-identified as White, slightly surpassing the proportion of White residents in NH (89%).

Training Preferences

Participants displayed significant interest in the provided topics, with a substantial proportion (66% to 75%) indicating they were very or extremely interested in each topic. The intersection of gender diversity and trauma garnered the highest overall rating, indicating a prominent area of focus. Most agencies (72% to 81%) indicated the capacity to deploy 1-10 staff members to trainings, regardless of the specific training content. Participants also preferred concise training formats, notably favoring half-day or 1-day sessions, with some interest in a 2-day training format.

Role and Engagement Alignment

The survey grouped practices into three categories that are essential to inclusive care: trauma-informed, disability-informed, and LGBTQ+-informed. The analyses revealed notable alignments between perceived role and engagement in many practices, particularly within developmental disability and educational institutions. However, these alignments often materialized as strong congruence paired with low role scores, meaning sectors viewed certain practices as only a small part of their role and, therefore, needed more consistent active engagement in those practices. See Figure 1 for detailed information.

| Sectors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practices | MH (n=8) | DD (n=6) | Peds (n=4) | Schools (n=16) | |

| Trauma-Informed | Use formal screening measures for current or past trauma, abuse and/or neglect | 0.66 (HR/HE) |

0.82* (LR/LE) |

-0.13 (HR/LE) |

0.48 (LR/LE) |

| Integrate trauma/neglect into your diagnoses, case conceptualizations, or treatment/case plans | -0.25 (HR/HE) |

0.86* (HR/HE) |

1.00* (HR/HE) |

0.74* (LR/HE) |

|

| Ask about experiences with grief & loss (including placement changes) | 0.74* (HR/HE) |

0.92* (LR/HE) |

0.87 (HR/HE) |

0.80* (LR/LE) |

|

| Ask about experiences with bullying and/or peer victimization/rejection | 0.67 (HR/HE) |

0.79 (LR/LE) |

1.00* (HR/HE) |

0.76* (HR/HE) |

|

| Ask about experiences with discrimination | 0.55 (HR/HE) |

0.71 (LR/LE) |

0.82 (HR/LE) |

0.72* (LR/LE) |

|

| Make referrals for trauma-informed mental health services | -0.2 (HR/HE) |

-0.91* (HR/HE) |

0 (HR/HE) |

0.83* (HR/HE) |

|

| Disability-Informed | Ask about experiences with seclusion and restraint | 0.86* (HR/LE) |

1.00* (LR/LE) |

(ND) | 0.75* (LR/LE) |

| Ask about sensory sensitivities or other triggers that result in distress for youth with IDD | 0.80* (HR/HE) |

0.79 (HR/HE) |

0.92 (HR/HE) |

0.91* (HR/HE) |

|

| Provide treatment or services that adapts to the needs of youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities | 0.95* (HR/HE) |

0.37 (HR/HE) |

1.00* (HR/HE) |

0.82* (HR/HE) |

|

| Make referrals for services related to intellectual and developmental disabilities | 0.49 (HR/HE) |

0.55 (HR/HE) |

0.33 (HR/HE) |

0.79* (HR/HE) |

|

| LGBTQ+-Informed | Ask about sexual orientation (teens) | 1.00* (HR/HE) |

0.90* (LR/LE) |

(ND) | 0.09 (LR/LE) |

| Ask about gender identity | 1.00* (HR/HE) |

0.46 (LR/LE) |

(ND) | 0.08 (LR/LE) |

|

| Ask about a child’s preferred pronouns | 1.00* (HR/HE) |

0.84* (LR/LE) |

1.00* (HR/HE) |

0.61* (LR/LE) |

|

| Make referrals to gender-and/or-sexuality-affirming services | 0.62 (HR/HE) |

0.45 (LR/LE) |

(ND) | 0.52* (LR/LE) |

|

| Light Green | High role/High engagement (HR/HE) |

|---|---|

| Darker Red | Low Role/Low Engagement (LR/LE) |

| Lighter Red | High Role/Low Engagement (HR/LE) |

| Tan | Low Role/High Engagement (LR/HE) |

| Gray | Not enough data to run correlations (ND) |

High role/high engagement means respondents felt that the practice was part of their role and they were engaging in the practice. Low role/low engagement means respondents felt that the practice was not part of their role and they were not engaging in the practice. High role/low engagement means respondents felt that the practice was part of their role but they were not engaging in the practice. Low role/high engagement means respondents did not feel the practice was part of their role but they did engage in the practice.

A high correlation is one that is greater than or equal to 3.1, a low score is one that is less than or equal to 3.09. For example, high role/low engagement score (yellow) means a role score greater than or equal to 3.1, and an engagement score less than or equal to 3.09. The score range is 0-5.

*p < .05

Trauma-Informed Practices

Sectors such as mental health and pediatrics recognized the significance of trauma-informed practices within their roles. Still, they did not often incorporate them into their operation (weak congruence, high role score). For pediatrics, deficits were found in using trauma screening measures and making referrals. Creating trauma-integrated care plans was considered necessary for the mental health sector, but they were less likely to engage in the practice.

Both the developmental disability and school sectors perceived some of the trauma-informed practices as outside their role/small part of their role. They lacked active involvement in these practices (moderate/strong congruence, low role score). For the developmental disability sector, these included roles and engagement practices around grief, loss, and bullying. For schools, low role/engagement ratings centered on making a trauma-integrated care/case plan. Both developmental disability and school sectors perceived using trauma screening measures and asking about discrimination as practices outside their role/small part of their role and lacked active involvement in these practices.

Disability-Informed Practices

For disability-informed practices, the gap between recognition of the practice as within their role and engagement in that practice was narrower. All the sectors showed strong congruence across multiple practices for most categories. However, developmental disability as a sector displayed more variable levels of congruence for different practices. Both the developmental disability and school sectors perceived asking about seclusion and restraint as a practice outside their role/small part of their role and a lack of active involvement in asking about seclusion and restraint (moderate/strong congruence, low role score). The mental health, developmental disability, and pediatric sectors also reported slightly reduced congruence for making referrals to IDD services than they reported for other disability-informed practices (moderate congruence). Overall, there is an acknowledgment of the sectors’ roles in disability-informed care, and their level of engagement was aligned with how much they perceived practice as part of their role (e.g., when perceived as an important part of a role, they reported high engagement in the practice).

LGBTQ+-Informed Practices

Developmental disability and school sectors perceived all LGBTQ+ practices as outside their role/small part of their role and lacked involvement in the practice (moderate/strong congruence, low role score). Pediatrics recognized LGBTQ+ awareness and inclusion as part of their role but were not often engaging in the practice.

Leadership Implementation and Inner Setting

Although participants acknowledged some existing leadership efforts to support training and practice changes in these domains, participants within pediatrics and educational institutions noted a need for leadership efforts to move forward many practices. Challenges related to staffing and budgets persist, even as we transition into a period after the pandemic.

Goal 2 – Training Series for Multiple Care Sectors

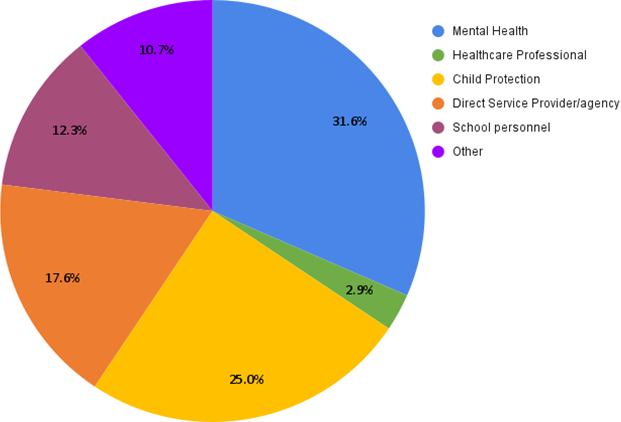

In the first two years of our project, we trained 966 individuals through various methods; 142 attended more than one training session. We offered a variety of training modules, including the triple intersection training series (n = 467) and the CARE training series (n = 94). Of those who attended our trainings, 554 provided data on what professional sector they work in, the most represented being mental health and child protection (Figure 2).

Note. The 554 individuals surveyed about their sector were from a variety of different training types, including the triple intersection, CARE, as well as organization specific training.

Triple Intersection Training

We delivered a four-session pilot program in the fall of 2022. Attendance records indicated that of the four sessions offered, 189 individuals participated in a single session, with the initial triple intersection session being the most popular (n = 182). Twenty-eight participants attended at least two sessions, seven of whom attended all four.

We delivered a revised four-session program in Spring of 2023. In total, 101 unique people attended at least one training. According to attendance records, five people attended all four trainings, 15 people attended three trainings, and 23 people attended two trainings.

When asked to retrospectively self-assess their trauma-informed service approach before and after attending either triple intersection training, participants (n = 33, 19) generally noted an increase in the knowledge of, consideration, understanding, and implementation of trauma-informed service behaviors.

Across both training series, participants noted an increase in the ability to identify needs or actions to enhance “felt” safety, have conversations about trauma, use strategies that enable traumatized children to succeed, and they noted increased awareness and attitude shifts, as well as practice changes and increased energy to pursue goals related to this topic (Figure 3). However, the second training series saw a great increase in knowledge, specifically in understanding the impact of trauma/neglect on a child’s behavior and development. When asked about the extent to which they considered trauma in their work with youths and considering the use of strength-based principles, participants in both training reported engaging in these behaviors “often” or “always” after the training series as compared to before.

| I understand the impact of trauma and/or neglect on a child’s development and behaviors. |  |

| I have a clear understanding of what trauma-informed practice means in my professional role. |  |

| I can identify actions that enhance psychological “felt” safety and security for children and their caregivers. |  |

| I know how to identify trauma-related needs of children and their caregivers. |  |

| I am able to have conversations about trauma with caregivers of children in a way they understand. |  |

| I use strategies that enable traumatized children to succeed in relationships, behaviorally and academically. |  |

| I regularly discuss trauma issues related to children with cross-systems partners. |  |

| I have the energy to pursue goals related to serving neuro and/or gender-diverse youth who have experienced trauma. |  |

| Consider trauma in our work with youth |  |

| Consider strengths-based principles when working with neuro and/or gender-diverse youth who have experienced trauma |  |

CARE Training

We distributed a training evaluation survey following three training sessions in fall 2022 and spring 2023. A total of 52 people completed the survey, including 37 ciswomen, eight cismen, two transgender individuals, one non-binary person, and four people who chose not to answer. Across trainings, people evaluated the training positively, found the skills taught to be useful in their job, felt comfortable implementing the skills on their own, and found the training to be engaging and helpful. All participants agreed or strongly agreed that they would recommend this training to a colleague. However, a few participants disagreed with statements about the extent to which they learned new approaches and how trauma issues were incorporated into the training. Additionally, one training found that participants (up to 24%) disagreed or strongly disagreed that they had learned new approaches (praise, describing behavior, paraphrasing) that they had not previously used. Across trainings, six of 52 participants thought integrating trauma more fully and discussing autism in more detail could be areas for growth.

Goal 3 – Screening and Assessment

Thus far, we have completed 49 trauma/PTSD (CATS-2) screenings through our medical center’s autism evaluations, gender-affirming care, and other neurodiversity-related services. Between February and March of 2023, four parent/child dyads completed the quality of life (PROMIS) measure. We are unsure if this captures all completed PROMIS measures but will continue to assign the measure to families being seen within behavioral and neurodevelopmental services. For now, we only have counts of youth screened.

Goal 4 – Inclusion of People with Lived Experience

In the first 2 years we held six Advisory Board meetings and plan to continue to meet quarterly. These meetings are regularly attended by 8-10 of the 12 full members. We have always had a voice of lived experience present, including some combination of a parent and a young adult. In years 1-2 we contracted for 5 hours/month with a young adult who identifies as nonbinary and autistic, and consulted with them on multiple grant activities. In Year 3, we increased this to 17 hours a month or 200 hours/year. This young adult was a co-presenter for six training sessions with our team in the first 2 years and plans to continue to be part of delivering the Triple Intersection training. Finally, we are currently writing an academic paper with a licensed clinician with professional and lived experience focused on the intersection of gender diversity and trauma. This individual joins bi-monthly paper meetings and is writing a significant part of the paper.

Discussion

Our statewide readiness assessment showed training gaps in trauma-informed practices, especially in mental health and pediatrics, and highlighted disparities in LGBTQ+-informed practices. The assessment also highlighted the necessity of leadership to drive changes. Thus far, our 2-year training initiative involving 966 individuals has positively impacted understanding and implementing trauma-informed service behaviors. Initial training feedback emphasized the need for deeper integration of trauma considerations and detailed discussions on autism, which we have since started to implement. To date, we have administered 49 trauma/PTSD (CATS-2) and two quality of life (PROMIS) screenings for autism evaluations, gender-affirming care, and neurodiversity-related services at the medical center. Our team emphasized partnerships with individuals with lived experience in project guidance, training delivery, and academic contributions via an advisory board, consulting, and contracting.

Our readiness assessment surveyed key stakeholders at the director’s level and examined three areas of interest: trauma-, LBGTQ+-, and disability-informed services. Results found congruence among schools and developmental disability agencies (saw practices as not part of their role and did not engage in these practices) in LGBTQ+- and trauma-informed practices. This is not unique to our state. Similarly, a Swedish study examined inpatient center staff attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people with intellectual disabilities and found staff was uncertain about LGBTQ+-affirmative approaches when working with their patients (Sommarö et al., 2020). Schools and developmental disability agencies may benefit from introductory training in practices to increase buy-in and role expansion in LGBTQ+ practices. Sectors that saw specific practices as part of their role (mental health and pediatrics in trauma-informed care), but were not engaging in the practices, would benefit from more advanced training that focuses on practice implementation. Findings showed that targeted training in leadership may increase buy-in and aid in implementing these practices. However, these practices may not be top priorities because of consistent staffing and budget issues. McNally et al. (2022) reported similar barriers to implementing trauma-informed practices in residential centers serving adults with IDD. Time for training, resources, and challenges in staff recruitment and retention are among some of the biggest barriers faced.

Our triple intersection training proved helpful in increasing self-reported knowledge of trauma-informed services, the ability to identify the needs of traumatized people, have conversations around trauma, and strategies that enable traumatized people to succeed in the context of gender diversity and/or IDD. These findings align with existing literature supporting trauma-informed care training. A systematic review of 23 trauma-informed trainings ranging from 2 hours to 19 days implemented in youth psychiatric settings, child welfare, juvenile justice, or similar settings found that most training significantly increased staff knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and client outcomes (Purtle, 2020). Twelve of those studies administered the posttest immediately after the conclusion of the training, like ours. Purtle found studies that followed up with trainees up to 1 year later reported variable information retention (between 12-81%). The extent of our training efficacy over time is unknown currently. However, post-training assessments through a follow-up readiness assessment at the midpoint and end of our project will help assess the reach and impact of our trainings. CARE trainees reported similar increases in knowledge and skills when working with youth at the intersection of trauma and IDD. Non-IDD-specific single-session CARE training has previously been implemented in foster care systems, pediatric primary care, schools, and residential care nationwide (Gurwitch et al., 2016). Sector buy-in, agency support, and commitment to cultural change were identified as important factors in the implementation and sustainability of CARE training and skills (Gurwitch et al., 2016). In Year 2 of our project, we delivered CARE training at two different residential facilities at their request. Increasing sector buy-in will be paramount in extending the reach of this training to other sectors, including parents/caregivers, throughout the state.

Implementing the trauma/PTSD and quality of life measures in our IDD and gender services was possible through the help of key stakeholders in the institution. We need more data on the feasibility and acceptability of this initiative, although we do have a wealth of literature to draw upon from prior efforts to install screenings into healthcare settings. Perhaps the most promising and well-known example is the growing installation of trauma screening in pediatric practices. Screening for trauma has been successful in increasing rates of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) identification (DiGangi & Negriff, 2020; DiGiovanni et al., 2023; Kia-Keating et al., 2019), which in turn can lead to the use of evidence-based interventions and education promoting resilience (ACEs Aware, 2020). However, research finds implementation of trauma screeners often takes time, provider buy-in and education, and changes in clinic workflow (DiGangi & Negriff, 2020; Forkey et al., 2021; Keeshin et al., 2020). We intend to continue administering the screening measures in our hospital and expand these practices into affiliated hospitals and practices. We also hope to gather feedback from providers and families on the screening process and measures. Finally, we will use information from these measures and other electronic health record variables to better characterize our hospital’s patients and build services to meet their needs.

We prioritize amplifying lived experiences in our project. Parents and young adults actively contributed, enriching our approach through Advisory Board meetings, developing and conducting trainings, and writing academic papers. Inclusion informs and refines our initiatives and helps us align with diverse perspectives for more impactful project outcomes. Incorporating lived experiences aligns with international and national mental health research standards. International funding organizations like the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), and the Welcome Trust are increasingly mandating that mental health research teams include people with lived experience in the development process (Lloyd et al., 2023). Programs like the Queensland Framework for the Mental Health Lived Experience Workforce and a plethora of peer support and Community Health Worker (CHW) programs have laid the foundation for incorporating people with lived experience into the workplace (Byrne et al., 2019). This commission created standards that reflect how people with lived experience and their perspectives help inform the academic/ research world about the realities of services and things that need to change. These insights can help bridge the gap between the medical world and those with negative treatment experiences, fostering trust. Future plans for this project prioritize continued collaboration with the gender-diverse/IDD/trauma-exposed community.

Limitations

Our readiness assessment included only a small sample from one state and only those at the director’s level. In addition, we were not able to draw conclusions from ABA providers given their very small sample. These limitations leave major gaps in perspectives and generalizability. Our training evaluations had no control group, so there is no way to confirm that changes in trainee knowledge, behaviors, and intentions were because of the training. We were also limited to self-report training evaluations. Our screening efforts have had an uneven uptake, partly due to provider burden, workflow difficulties (e.g., iPad distribution before visits), and parents needing to complete the measures before their visits when sent through an online portal. Much work is needed to improve workflows and problem-solve the most effective and efficient ways of gathering screening information. Finally, we have yet to meet all the recommendations by reputable organizations around the full inclusion of people with lived experience. In an ideal effort, we would have more comprehensive and equal partnerships across every planning, implementation, and evaluation activity.

Future Directions

Our team will soon administer a follow-up readiness assessment to assess changes in our state and various sectors regarding readiness to adopt trauma-, disability-, and LGBTQ+-informed “roles” and engagement in these practices. Leaders trying to conduct a similar assessment in their region or state could consider ways to gather perspectives from direct-care staff, parents, and youth with lived experience to fully inform their planning. We will continue our training efforts and will revise training content based on evaluations to continuously improve our project. In future efforts, we suggest the use of behavioral measures following trainings. Although burdensome and resource-heavy, behavioral measures would likely lead to more accurate outcomes. If possible, future research should also consider using control groups to evaluate the impacts of training. Our project aims to continuously improve our screening processes so that they more efficiently integrate into the workflow and remain useful to both providers and researchers. In time, we aim to examine screening variables related to trauma and PTSD, IDD status, and gender identity to characterize our sample and understand the relationships between these variables. We also aim to expand our screening efforts into partnering clinics serving youth with IDD and gender-related needs. We aim to expand our partnerships more fully with provider partners, parent partners, and people with lived experience. For example, we hope to provide CARE training to parents and engage the ABA community and people with lived experience to build training and services towards a more holistic, trauma-informed approach to behavioral interventions for youth with IDD.

Conclusion

As we progress into year 3 of the 5-year program, Project ATTAIN will continue to provide workforce training, increase capacity for trauma screening and identification, increase the accessibility of evidence-based treatment, and raise public awareness across the state of NH and beyond, all through the inclusion and guidance of people with lived experience. Trauma and other adversities disproportionately affect people with IDD and/or gender diversity. This reality requires caregivers, the workforce, and communities to act in trauma-informed, gender-informed, and disability-informed ways to mitigate the impact on mental health, physical well-being, and social outcomes. Nevertheless, we acknowledge the unique resilience and inherent strength these communities possess and aim to bolster that resilience through Project ATTAIN.

References

Aarons, G. A., Ehrhart, M. G., & Farahnak, L. R. (2014). The Implementation Leadership Scale (ILS): Development of a brief measure of unit level implementation leadership. Implementation Science, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-45

ACEs Aware. (2020, March). Provider Toolkit: Screening and responding to the impact of ACEs and toxic stress. Acesaware.org. https://www.acesaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ACEs-Aware-Provider-Toolkit-5.21.20.pdf

American Psychological Association, Division 16 & 44. (2015). Key terms and concepts in understanding gender diversity and sexual orientation among students. https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/ programs/safe-supportive/lgbt/key-terms.pdf

Aparicio-García, M. E., Díaz-Ramiro, E. M., Rubio-Valdehita, S., López-Núñez, M. I., & García-Nieto, I. (2018). Health and well-being of cisgender, transgender and non-binary young people. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10). https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ijerph15102133

Baladerian, N. J. (n.d.). Trauma and PTSD in individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. American Psychological Association, Division 56 Trauma Psychology. https://www.apatrauma division.org/files/59.pdf

Barnett, E. R., Yackley, C. R., & Licht, E. S. (2018). Developing, implementing, and evaluating a trauma-informed care program within a youth residential treatment center and special needs school. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 35(2), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 0886571X.2018.1455559

Berg, K. L., Shiu, C. S., Feinstein, R. T., Msall, M. E., & Acharya, K. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences are associated with unmet healthcare needs among children with autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of Pediatrics, 202, 258-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.021

Bethell, C., Jones, J., Gombojav, N., Linkenbach, J., & Sege, R. (2019). Positive childhood experiences and adult mental and relational health in a statewide sample: Associations across adverse experiences levels. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(11). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3007

Bottema-Beutel, K., Kapp, S. K., Lester, J. N., Sasson, N. J., & Hand, B. N. (2021). Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions for autism researchers. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 18-29. https://doi.org/ 10.1089/aut.2020.0014

Brendli, K. R., Broda, M. D., & Brown, R. (2022). Children with intellectual disability and victimization: A logistic regression analysis. Child Maltreatment, 27(3), 320–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1077559521994177

Burgess, A. F., & Gutstein, S. E. (2007). Quality of life for people with autism: Raising the standard for evaluating successful outcomes. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 12(2), 80-86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2006.00432.x

Byrne, L., Wang, L., Roennfeldt, H., Chapman, M., & Darwin, L. (2019). Queensland framework for the development of the mental health lived experience workforce. Queensland Government: Brisbane. https://www.qmhc.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/qmhc_lived_experience_workforce_framework_web.pdf

Canvin, L., Twist, J., & Solomons, W. (2022). How do mental health professionals describe their experiences of providing care for gender-diverse adults? A systematic literature review. Psychology & Sexuality, 13(3), 717-741. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.1916987

Coleman, E., Radix, A. E., Bouman, W. P., Brown, G. R., De Vries, A. L., Deutsch, M. B., Ettner, R., Fraser, L., Goodman, M., Green, J., Hancock, A. B., Johnson, T. W., Karasic, D. H., Knudson, G. A., Leibowitz, S. F., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Monstrey, S. J., Motmans, J., Nahata, L., … Arcelus, J. (2022). Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender-diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health, 23(sup1), S1-S259. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

Crouch, E., Radcliff, E., Brown, M. J., & Hung, P. (2023). Association between positive childhood experiences and childhood flourishing among US children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 44(4), e255–e262. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000001181

de Vries, A. L. C., Noens, I. L. J., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Van Berckelaer-Onnes, I. A., & Doreleijers, T. A. (2010). Autism spectrum disorders in gender dysphoric children and adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 930-936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0935-9

DiGangi, M. J., & Negriff, S. (2020). The implementation of screening for adverse childhood experiences in pediatric primary care. The Journal of Pediatrics, 222, 174–179.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.057

DiGiovanni, S. S., Frances, R. J. H., Brown, R. S., Wilkinson, B. T., Coates, G. E., Faherty, L. J., Craig, A. K., Andrews, E. R., & Gabrielson, S. M. (2023). Pediatric trauma and posttraumatic symptom screening at well-child visits. Pediatric Quality & Safety, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.1097% 2Fpq9.0000000000000640

Fernandez, M. E., Walker, T. J., Weiner, B. J., Calo, W. A., Liang, S., Risendal, B., Friedman, D. B., Tu, S. P., Williams, R. S., Jacobs, S., Herrmann, A. K., & Kegler, M. C. (2018). Developing measures to assess constructs from the inner setting domain of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implementation Science, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0736-7

Forkey, H. C., Griffin, J. L., & Szilagyi, M. (2021). Childhood trauma and resilience: A practical guide. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/9781610025072

Gorman, K. R., Shipherd, J. C., Collins, K. M., Gunn, H. A., Rubin, R. O., Rood, B. A., & Pantalone, D. W. (2022). Coping, resilience, and social support among transgender and gender-diverse individuals experiencing gender-related stress. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 9(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000455

Graham Holmes, L., Zampella, C. J., Clements, C., McCleery, J. P., Maddox, B. B., Parish‐Morris, J., Udhnani, M. D., Schultz, R. T., & Miller, J. S. (2020). a lifespan approach to patient‐reported outcomes and quality of life for people on the autism spectrum. Autism Research, 13(6), 970-987. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2275

Grant, J. M., Mottet, L. A., & Tanis, J., Harrison, J., Herman, J. L., & Keisling, M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. https://transequality.org/ sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf

Gurwitch, R. H., Messer, E. P., Masse, J., Olafson, E., Boat, B. W., & Putnam, F. W. (2016). Child-Adult Relationship Enhancement (CARE): An evidence-informed program for children with a history of trauma and other behavioral challenges. Child Abuse & Neglect, 53, 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.016

Han, D., Dieujuste, N., Doom, J. R., & Narayan, A. J. (2023). A systematic review of positive childhood experiences and adult outcomes: Promotive and protective processes for resilience in the context of childhood adversity. Child Abuse & Neglect, 144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2023. 106346

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Hershkowitz, I., Lamb, M. E., & Horowitz, D. (2007). Victimization of children with disabilities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(4), 629-635. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0002-9432. 77.4.629

Hisle-Gorman, E., Landis, C. A., Susi, A., Schvey, N. A., Gorman, G. H., Nylund, C. M., & Klein, D. A. (2019). Gender dysphoria in children with autism spectrum disorder. LGBT Health, 6(3), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2018.0252

Ijezie, O. A., Healy, J., Davies, P., Balaguer-Ballester, E., & Heaslip, V. (2023). Quality of life in adults with Down syndrome: A mixed methods systematic review. PloS One, 18(5). https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0280014

Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., & Underwood, J. M. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students – 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67–71. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3

Jones, L., Bellis, M. A., Wood, S., Hughes, K., McCoy, E., Eckley, L., Bates, G., Milton, C., Shakespeare, T., & Officer, A. (2012). Prevalence and risk of violence against children with disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet, 380(9845), 899-907. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60692-8

Kallitsounaki, A., & Williams, D. M. (2022). Autism spectrum disorder and gender dysphoria/incongruence. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53, 3103-3117 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05517-y

Keeshin, B., Byrne, K., Thorn, B., & Shepard, L. (2020). Screening for trauma in pediatric primary care. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22, 1-8. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11920-020-01183-y

Kerns, C. M., Robins, D. L., Shattuck, P. T., Newschaffer, C. J., & Berkowitz, S. J. (2023). Expert consensus regarding indicators of a traumatic reaction in autistic youth: a Delphi survey. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 64(1), 50-58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13666

Kia-Keating, M., Barnett, M. L., Liu, S. R., Sims, G. M., & Ruth, A. B. (2019). Trauma-Responsive Care in a Pediatric Setting: Feasibility and Acceptability of Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(3-4), 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/ ajcp.12366

Kildahl, A. N., Helverschou, S. B., Bakken, T. L., & Oddli, H. W. (2020). “If we do not look for it, we do not see it”: Clinicians’ experiences and understanding of identifying post‐traumatic stress disorder in adults with autism and intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(5), 1119-1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12734

Little, T. D., Chang, R., Gorrall, B. K., Waggenspack, L., Fukuda, E., Allen, P. J., & Noam, G. G. (2020). The retrospective pretest–posttest design redux: On its validity as an alternative to traditional pretest–posttest measurement. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(2), 175-183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419877973

Lloyd, A., Wu, T., Lucas, L., Agunbiade, A., Saleh, R., Fearon, P., & Viding, E. (2023). No decision about me, without me: Collaborating with children and young people in mental health research [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/4sxuh

Maclean, M. J., Sims, S., Bower, C., Leonard, H., Stanley, F. J., & O’Donnell, M. (2017). Maltreatment risk among children with disabilities. Pediatrics, 139(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1817

Mandell, D. S., Walrath, C. M., Manteuffel, B., Sgro, G., & Pinto-Martin, J. A. (2005). The prevalence and correlates of abuse among children with autism served in comprehensive community-based mental health settings. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(12), 1359–1372. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.chiabu.2005.06.006

McDonnell, C. G., Boan, A. D., Bradley, C. C., Seay, K. D., Charles, J. M., & Carpenter, L. A. (2019). Child maltreatment in autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability: Results from a population‐based sample. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(5), 576-584. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jcpp.12993

McNally, P., Irvine, M., Taggart, L., Shevlin, M., & Keesler, J. (2022). Exploring the knowledge base of trauma and trauma-informed care of staff working in community residential accommodation for adults with an intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 35(5), 1162-1173. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.13002

Mevissen, L., & de Jongh, A. (2010). PTSD and its treatment in people with intellectual disabilities: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(3), 308-316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr. 2009.12.005

Meyer, T., Richter, S., & Raspe, H. (2013). Agreement between pre-post measures of change and transition ratings as well as then-tests. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, 1-10. https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2288-13-52

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2020a). Child adult relationship enhancement. https://www. nctsn.org/interventions/child-adult-relationship-enhancement

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2020b). The impact of trauma on youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A fact sheet for providers. https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/ files/resources/fact-sheet/the_impact_of_trauma_on_ youth_with_intellectual_and_developm ental_disabilities_a_fact_sheet_for_providers.pdf

O’Donoghue, E. M., Pogge, D. L., & Harvey, P. D. (2020). The impact of intellectual disabilityand autism spectrum disorder on restraint and seclusion in pre-adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 13(2), 86-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 19315864.2020.1750742

Olson, K. R., Durwood, L., DeMeules, M., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2016). Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics, 137(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3223

Price, M. A., Hollinsaid, N. L., Bokhour, E. J., Johnston, C., Skov, H. E., Kaufman, G. W., Sherian, M., & Olezeski, C. (2023). Transgender and gender-diverse youth’s experiences of gender-related adversity. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 40(3), 361-380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00785-6

Pampati, S., Andrzejewski, J., Steiner, R. J., Rasberry, C. N., Adkins, S. H., Lesesne, C. A., Boyce, L., Grose, R. G., & Johns, M. M. (2021). “We deserve care and we deserve competent care”: Qualitative perspectives on health care from transgender youth in the southeast United States. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 56, 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2020.09.021

Purtle J. (2020). Systematic review of evaluations of trauma-informed organizational interventions that include staff trainings. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 21(4), 725–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1524838018791304

Qualtrics. (2020). Qualtrics. Provo, UT. https://qualtrics.com

Reisner, S. L., Benyishay, M., Stott, B., Vedilago, V., Almazan, A., & Keuroghlian, A. S. (2022). Gender-affirming mental health care access and utilization among rural transgender and gender-diverse adults in five northeastern U.S. Transgender Health, 7(3), 219-229. https://doi.org/10.1089% 2Ftrgh.2021.0010

Reisner, S. L., White Hughto, J. M., Gamarel, K. E., Keuroghlian, A. S., Mizock, L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2016). Discriminatory experiences associated with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among transgender adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(5), 509–519. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/cou0000143

Russell, S. T., Pollitt, A. M., Li, G., & Grossman, A. H. (2018). Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(4), 503-505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003

Sachser, C., Berliner, L., Risch, E., Rosner, R., Birkeland, M. S., Eilers, R., Hafstad, G. S., Pfeiffer, E., Plener, P. L., & Jensen, T. K. (2022). The Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen 2 (CATS-2)–validation of an instrument to measure DSM-5 and ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD in children and adolescents. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2022. 2105580

Scheffers, F., van Vugt, E., & Moonen, X. (2023). Resilience in the face of adversity: How people with intellectual disabilities deal with challenging times. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. https://doi.org/10.1177/17446295231184504

Schnarrs, P. W., Stone, A. L., Salcido, R., Jr, Baldwin, A., Georgiou, C., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2019). Differences in adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and quality of physical and mental health between transgender and cisgender sexual minorities. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 119, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.09.001

Solomon, D. T., Combs, E. M., Allen, K., Roles, S., DiCarlo, S., Reed, O., & Klaver, S. J. (2021). The impact of minority stress and gender identity on PTSD outcomes in sexual minority survivors of interpersonal trauma. Psychology & Sexuality, 12(1-2), 64-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899. 2019.1690033

Sommarö, S., Andersson, A., & Skagerström, J. (2020). A deviation too many? Healthcare professionals’ knowledge and attitudes concerning patients with intellectual disability disrupting norms regarding sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(6), 1199-1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12739

Son, E., Parish, S. L., & Peterson, N. A. (2012). National prevalence of peer victimization among young children with disabilities in the United States. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(8), 1540-1545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.04.014

Strang, J. F., Meagher, H., Kenworthy, L., De Vries, A. L. C., Menvielle, E., Leibowitz, S., Janssen, A., Cohen-Kettenis, P., Shumer, D. E., Edwards-Leeper, L., Pleak, R. R., Spack, N., Karasic, D. H., Schreier, H., Balleur, A., Tishelman, A., Ehrensaft, D., Rodnan, L., Kuschner, E. S., … Anthony, L. G. (2016). Initial clinical guidelines for co-occurring autism spectrum disorder and gender dysphoria or incongruence in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(1), 105-115. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1228462

Taboas, A., Doepke, K., & Zimmerman, C. (2023). Preferences for identity-first versus person-first language in a US sample of autism stakeholders. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 27(2), 565–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221130845

Trinh, M. H., Aguayo-Romero, R. & Reisner, S. L. (2022). Mental health and substance use risks and resiliencies in a U.S. sample of transgender and gender-diverse adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57, 2305–2318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02359-y

Warrier, V., Greenberg, D. M., Weir, E., Buckingham, C., Smith, P., Lai, M. C., Allison, C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2020). Elevated rates of autism, other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric diagnoses, and autistic traits in transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Nature Communications, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17794-1