Transition to Empire: States, Cities, and New Religions (600 – 321 BCE)

The sixth century begins a transitional period in India’s history marked by important developments. Some of these bring to fruition processes that gained momentum during the late Vedic Age. Out of the hazy formative stage of state development, sixteen powerful kingdoms and oligarchies emerged. By the end of this period, one will dominate. Accompanying their emergence, India entered a second stage of urbanization, as towns and cities become a prominent feature of northern India. Other developments were newer. The caste system took shape as an institution, giving Indian society one of its most distinctive traits. Lastly, new religious ideas were put forward that challenged the dominance of Brahmanism.

States and Cities

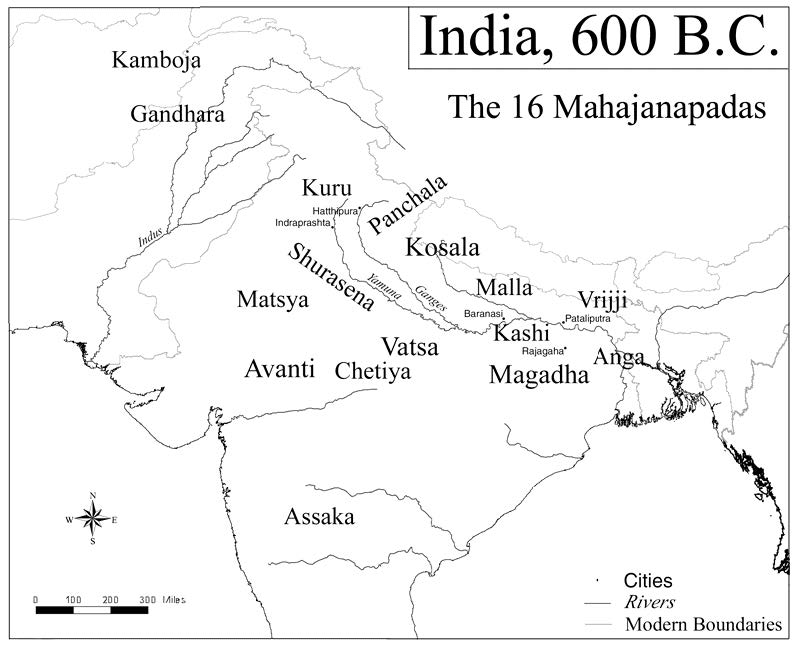

The kingdom of Magadha became the most powerful among the sixteen states that dominated this transitional period, but only over time. At the outset, it was just one of eleven located up and down the Ganges River (see Map 3.7). The rest were established in the older northwest or central India. In general, larger kingdoms dominated the Ganges basin while smaller clan-based states thrived on the periphery. They all fought with each other over land and resources, making this a time of war and shifting alliances.

The victors were the states that could field the largest armies. To do so, rulers had to mobilize the resources of their realms. The Magadhan kings did this most effectively. Expansion began in 545 BCE under King Bimbisara. His kingdom was small, but its location to the south of the lower reaches of the Ganges River gave it access to fertile plains, iron ore, timber, and elephants. Governing from his inland fortress at Rajagriha, Bimbisara built an administration to extract these resources and used them to form a powerful military. After concluding marriage alliances with states to the north and west, he attacked and defeated the kingdom of Anga to the east. His son Ajatashatru, after killing his father, broke those alliances and waged war on the Kosala Kingdom and the Vrijji Confederacy. Succeeding kings of this and two more Magadhan dynasties continued to conquer neighboring states down to 321 BCE, thus forging an empire. But its reach was largely limited to the middle and lower reaches of the Ganges River.

To the northwest, external powers gained control. As we have seen, the mountain ranges defining that boundary contain passes permitting the movement of peoples. This made the northwest a crossroads, and, at times, the peoples crossing through were the armies of rulers who sought to control the riches of India. Outside powers located in Afghanistan, Iran, or beyond might extend political control into the subcontinent, making part of it a component in a larger empire.

One example is the Persian Empire (see Chapter 5). During the sixth century, two kings, Cyrus the Great and Darius I, made this empire the largest in its time. From their capitals on the Iranian Plateau, they extended control as far as the Indus River, incorporating parts of northwest India as provinces of the Persian Empire (see Map 3.8). Another example is Alexander the Great (also see Chapter 5). Alexander was the king of Macedon, a Greek state. After compelling other Greeks to follow him, he attacked the Persian Empire, defeating it in 331 BCE. That campaign took his forces all the way to mountain ranges bordering India. Desiring to find the end of the known world and informed of the riches of India, Alexander took his army through the Khyber Pass and overran a number of small states and cities located in the Punjab. But to Alexander’s dismay, his soldiers refused to go any further, forcing him to turn back. They were exhausted from years of campaigning far from home and discouraged by news of powerful Indian states to the east. One of those was the kingdom of Magadha (see Map 3.9).

Magadha’s first capital—Rajagriha—is one of many cities and towns with ruins dating back to this transitional period. Urban centers were sparse during the Vedic Age but now blossomed, much like they did during the mature phase of the Harappan Civilization. Similar processes were at work. As more forests were cleared and marshes drained, the agricultural economy of the Ganges basin produced ever more surplus food. Population grew, enabling more people to move into towns and engage in other occupations as craftsmen, artisans, and traders. Kings encouraged this economic growth as its revenue enriched their treasuries. Caravans of ox-drawn carts or boats laden with goods travelling from state to state could expect to encounter the king’s customs officials and pay tolls. So important were rivers to accessing these trade networks that the Magadhan kings moved their capital to Pataliputra, a port town located on the Ganges (see Map 3.7). Thus, it developed as a hub of both political power and economic exchange. Most towns and cities began as one or the other, or as places of pilgrimage.

The Caste System

As the population of northern India rose and the landscape was dotted with more villages, towns, and cities, society became more complex. The social life of a Brahmin priest who served the king differed from that of a blacksmith who belonged to a town guild, a rich businessman residing in style in a city, a wealthy property owner, or a poor agricultural laborer living in a village. Thus, the social identity of each member of society differed.

In ancient India, one measure of identity and the way people imagined their social life and how they fit together with others was the varna system of four social classes. Another was caste. Like the varnas, castes were hereditary social classifications; unlike them, they were far more distinct social groups. The four-fold varna system was more theoretical and important for establishing clearly who the powerful spiritual and political elites in society were: the Brahmins and Kshatriya. But others were more conscious of their caste. There were thousands of these, and each was defined by occupation, residence, marriage, customs, and language. In other words, because “I” was born into such-and-such a caste, my role in society is to perform this kind of work. “I” will be largely confined to interacting with and marrying members of this same group. Our caste members reside in this area, speak this language, hold these beliefs, and are governed by this assembly of elders. “I” will also be well aware of who belongs to other castes, and whether or not “I” am of a higher or lower status in relation to them, or more or less pure. On that basis, “I” may or may not be able, for instance, to dine with them. That is how caste defined an individual’s life.

The lowest castes were the untouchables. These were peoples who engaged in occupations considered highly impure, usually because they were associated with taking life; such occupations include corpse removers, cremators, and sweepers. So those who practiced such occupations were despised and pushed to the margins of society. Because members of higher castes believed touching or seeing them was polluting, untouchables were forced to live outside villages and towns, in separate settlements.

The Challenge to Brahmanism: Buddhism

During this time of transition, some individuals became dissatisfied with life and chose to leave the everyday world behind. Much like the sages of the Upanishads, these renunciants, as they were known, were people who chose to renounce social life and material things in order that they might gain deeper insight into the meaning of life. Some of them altogether rejected Brahmanism and established their own belief systems. The most renowned example is Siddhartha Gautama (c. 563 – 480 BCE), who is otherwise known as the Buddha.

Buddha means “Enlightened One” or “Awakened One,” implying that the Buddha was at one time spiritually asleep but at some point woke up and attained insight into the truth regarding the human condition. His life story is therefore very important to Buddhists, people who follow the teachings of the Buddha.

Siddhartha was born a prince, son to the chieftain of Shakya, a clan-based state located at the foothills of the Himalaya in northern India. His father wished for him to be a ruler like himself, but Siddhartha went in a different direction. At twenty-nine, after marrying and having a son, he left home. Legends attribute this departure to his having encountered an old man, a sick man, a corpse, and a wandering renunciant while out on an excursion. Aging, sickness, and death posed the question of suffering for Siddhartha, leading him to pursue spiritual insight. For years, he sought instruction from other wanderers and experimented with their techniques for liberating the self from suffering through meditation and asceticism. But he failed to obtain the answers he sought.

Then, one day, while seated beneath a tree meditating for an extended period of time, a deepening calm descended upon Siddhartha, and he experienced nirvana. He also obtained insight into the reasons for human suffering and what was needful to end it. This insight was at the heart of his teachings for the remaining forty-five years of his life. During that time, he travelled around northern India teaching his dharma—his religious ideas and practices—and gained a following of students.

The principal teaching of the Buddha, presented at his first sermon, is called the Four Noble Truths. The first is the noble truth of suffering. Based on his own experiences, the Buddha concluded that life is characterized by suffering not only in an obvious physical and mental sense, but also because everything that promises pleasure and happiness is ultimately unsatisfactory and impermanent. The second noble truth states that the origin of suffering is an unquenchable thirst. People are always thirsting for something more, making for a life of restlessness with no end in sight. The third noble truth is that there is a cure for this thirst and the suffering it brings: nirvana. Nirvana means “blowing out,” implying extinction of the thirst and the end of suffering. No longer striving to quell the restlessness with temporary enjoyments, people can awaken to “the city of nirvana, the place of highest happiness, peaceful, lovely, without suffering, without fear, without sickness, free from old age and death.”1 The fourth noble truth is the Eight-Fold Path, a set of practices that leads the individual to this liberating knowledge. The Buddha taught that through a program of study of Buddhist teachings (right understanding, right attitude), moral conduct (right speech, right action, right livelihood), and meditation (right effort, right concentration, right mindfulness), anyone could become a Buddha. Everyone has the potential to awaken, but each must rely on his or her own determination.

After the Buddha died c. 480 BCE, his students established monastic communities known as the Buddhist sangha. Regardless of their varna or caste, both men and women could choose to leave home and enter a monastery as a monk or nun. They would shave their heads, wear ochre-colored robes, and vow to take refuge in the Buddha, dharma, and sangha. Doing so meant following the example of the Buddha and his teachings on morality and meditation, as well as living a simple life with like-minded others in pursuit of nirvana and an end to suffering.