The Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 CE)

Like every Chinese dynasty before it, the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 CE) was born out of turmoil and warfare. After the Tang Dynasty fell, China was once again divided up by numerous, contending kingdoms. The founder of the Song, Zhao Kuangyin [j-ow kwong-yeen], was a military commander and advisor to the emperor of one of these kingdoms, but after he died and his six-year-old son came to the throne, Zhao staged a coup. He left the capital with his troops, ostensibly to fight enemies to the north. But just outside the capital, his troops instead proclaimed him emperor, a title he accepted only with feigned reluctance and after his followers promised obedience and to treat the child emperor and people living in the capital environs humanely. On February 3, 960, the child was forced to abdicate, and Zhao took the throne as Emperor Taizu [tiedzoo]. He and his brother, the succeeding Emperor Taizong [tie-dzawng], ruled for the first forty years of a dynasty that would last over three hundred, laying the foundations for its prosperity and cultural brilliance. The Song Dynasty saw a total of eighteen emperors and is most notable for the challenges it faced from northern conquest dynasties, economic prosperity, a civil service examination system and the educated elite of scholar-officials it created, cultural brilliance, and footbinding.

During the Song, China once again confronted tremendous challenges from conquests by military confederations located along the northern border. So threatening and successful were these that the Song Dynasty counted as just one of many powerful players in a larger geopolitical system in Central and East Asia. The first two northern conquest dynasties, the Liao [lee-ow] and Jin [jean], emerged on the plains of Manchuria when powerful tribal leaders organized communities of hunters, fishers, and farmers for war (see Map 4.21).

As their power grew, they formed states and conquered territory in northern China, forcing the Chinese to pay them large subsidies of silk and silver for peace. So Chinese rulers and their councilors were in constant negotiations with peoples they viewed as culturally-inferior barbarians under conditions where they were forced to treat them as equals, as opposed to weaker tribute-paying states in a Chinese-dominated world. At first, they used a combination of defensive measures and expensive bilateral treaties, which did make for a degree of stability. But a high price was exacted. Halfway through the Song, the Jin Dynasty destroyed the Liao and occupied the entire northern half of China, forcing the Song court to move south (see Map 4.22). To rule Chinese possessions, Jin rulers even took on the trappings of Chinese-style emperors and developed a dual administrative system. Steppe tribes were ruled by a traditional military organization, while the farming population of China was governed with Chinese-style civilian administration. The Song Dynasty thus constantly faced the prospect of extinction and was challenged in its legitimacy by rival emperors claiming the right to rule the Chinese realm.

One reason Song monarchs were able to buy peace was the extraordinary prosperity during their rule and the resulting tax revenue made available. During those centuries, China was by many measures the most developed country in the world. In 1100 CE, the population was one hundred million, more than all of medieval Europe combined. That number doubled the population of 750 CE, just three hundred years prior. The reason for such growth was flourishing agricultural production, especially rice-paddy agriculture. More drought-resistant and earlier-ripening strains of rice, combined with better technology, lead to higher yields per acre.

The impact was enormous. The productivity of farmers stimulated other industries, such as ironworking. Estimates place iron production at as high as twenty thousand tons per year. That amount made iron prices low and, therefore, such products as spades, ploughshares, nails, axles, and pots and pans more cheaply available. Seeing its profitability, wealthy landowning and merchant families invested in metallurgy, spurring better technology. Bellows, for instance, were worked by hydraulic machinery, such as water mills. Explosives derived from gunpowder were engineered to open mines. Similar development of textile and ceramic industries occurred.

Indeed, during the Song, China underwent a veritable economic revolution. Improvements in agriculture and industry, combined with a denser population, spurred the commercialization of the economy. A commercialized economy is one that supports the pursuit of profit through production of specialized products for markets. A Song farmer, for instance, as opposed to just producing rice to get by, might rather purchase it on a market and instead specialize in tea or oranges. Since markets were proliferating in towns and cities and transport via land and water was now readily available, farmers could rely on merchants to market their goods across the country. To support this economic activity, the government minted billions of coins each year as well as the world’s first paper currency.

A denser population and sophisticated economy led to urbanization. During the Song, at a time when London had roughly fifteen thousand people, China had dozens of cities with over fifty thousand people and capitals with a half million. Song painted scrolls show crowds of people moving through streets lined with shops, restaurants, teahouses, and guest houses (see Figure 4.22).

To manage their realm, Song rulers implemented a national civil service examination to recruit men for office. Prior dynasties had used written examinations testing knowledge of Confucian classics to select men for office, but only as a supplement to recommendation and hereditary privilege. During the collapse of the Tang Dynasty, however, aristocratic families that had for centuries dominated the upper echelons of officialdom disappeared. The first Song emperor, Zhao Kuangyin, rode to power with the support of military men; having largely unified China, he then sought to restore civil governance based in Confucian principles of humaneness and righteousness. So he invited senior commanders to a party and, over a cup of wine, asked them to relinquish their commands for a comfortable retirement. They obliged. He and his successors consequently made the examination system the pre-eminent route to office, even establishing a national school system to help young men prepare for and advance through it. Thus, during the Song Dynasty, civil offices came to be dominated by men who had spent years, even decades, preparing for and passing through a complex series of exams. Hence, they were both scholars and officials. Success in entering this class placed a person at the pinnacle of society, guaranteeing them prestige and wealth. These scholar-officials, and their Confucian worldview, dominated Chinese society until the twentieth century.

In theory, since any adult male could take the examinations, the system was meritocratic. But in reality, because they were so difficult and quotas were set, very few actually passed them. Estimates suggest that only one in one hundred passed the lowest level exam. This ratio meant that, in order to succeed, a young man had to begin memorizing long classical texts as a child and to continue his studies until he passed or gave up hope. Only affluent families could afford to support such an education.

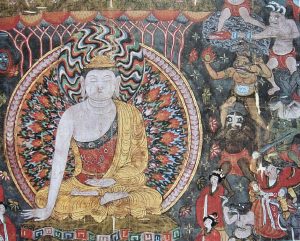

Nevertheless, the meritocratic ideal inspired people from all classes to try and so promoted literacy and a literary revival during the Song Dynasty. As a part of this revival and to provide a curriculum for education, scholar-officials sought to reinvigorate Confucianism. The philosophical movement they began is known as Neo-Confucianism. By the Song Dynasty, whereas Confucianism largely shaped personal behavior and social mores, Buddhist and Daoist explanations of the cosmos, human nature, and the human predicament dominated the individual’s spiritual outlook. NeoConfucians responded to this challenge by providing a metaphysical basis for Confucian morality and governance. Zhu Xi (1130 – 1200), arguably the most important philosopher in later imperial Chinese history, produced a grand synthesis that would shape the worldview of the scholar-official class. He argued that the cosmos consists of a duality of principles and a material force composing physical things. One principle underlies the cosmos and individual principles provide the abstract reason for individual things. In human beings, principle manifests as human nature, which is wholly good and the origins of the human capacity to become moral persons. However, an individual’s physical endowment obscures their good nature and leads to moral failings, which is why a rigorous Confucian curriculum of moral self-cultivation based in classical texts like Confucius’ Analects is necessary. Most importantly, Zhu Xi argued, individual morality was the starting point for producing a well-managed family, orderly government, and peace throughout the world.

|

|

|

Furthermore, during the Song Dynasty, moveable-type printing also began to be widely used, contributing to an increase in literacy and broader exposure to these new ideas. Chinese characters were carved on wood blocks, which were then arranged in boxes that could be dipped in ink and printed on paper (see Figure 4.23). Books on a multitude of topics–especially classics and histories– became cheaply and widely available, fueling a cultural efflorescence at a time when education had become paramount to climbing the social ladder. Other inventions that made China one of the most technologically innovative during this time include gunpowder weapons (see Figure 4.24) and the mariner’s compass.

Looked at from many angles, then, the Song was truly a dynamic period in China’s history. However, some observers have bemoaned the fact that footbinding began during this dynasty and see that practice as a symbol of increasing gender oppression. Scholars believe footbinding began among professional dancers in the tenth century and was then adopted by the upper classes. Over time it spread to the rest of Chinese society, only to end in the twentieth century. At a young age, a girl’s feet would be wrapped tightly with bandages so that they couldn’t grow, ideally remaining about four-inches long. That stunting made walking very difficult and largely kept women confined to their homes. Eventually, the bound foot, encased in an embroidered silk slipper, became a symbol of femininity and also one of the criteria for marriageability (see Figure 4.25).

|

|

|

More generally, social norms and the law did place women in a subordinate position. Whereas men dominated public realms like government and business, women married at a young age and lived out most of their lives in the domestic sphere. Indeed, in earlier times, China was patriarchal, patrilineal, and patrilocal. It was patriarchal because the law upheld the authority of senior males in the household and patrilineal because one’s surname and family property passed down the male line—though a wife did have control over her dowry. Importantly, ancestor worship, the pre-eminent social and religious practice in Chinese society, was directed toward patrilineal forbears. That is why it was important for the woman to move into the spouse’s home, where she would live together with her parents-in-law. Patrilocal describes this type of social pattern. Marriages were almost always arranged for the benefit of both families involved, and, during the wedding ceremony, the bride was taken in a curtained sedan chair to the husband’s home where she was to promise to obey her parents-in-law and then bow along with her husband before the ancestral altar. Ideally, she would become a competent household manager, educate the children, and demonstrate much restraint and other excellent interpersonal skills.

Although gender hierarchy was, therefore, the norm, other scholars have observed that ideals were not always reality and women did exercise their agency within the boundaries placed upon them. A wife could gain dignity and a sense of self-worth by handling her roles capably; she would also earn respect. Song literature further reveals that women were often in the fields working or out on city streets shopping. Among the upper classes, literacy and the ability to compose essays or poetry made a woman more marriageable. For this reason, some women were able to excel. Li Qingzhao [lee ching-jow] (c. 1084 – 1155) is one of China’s greatest poets (see Figure 4.27). She came from a prestigious scholar-official family. Her father was both a statesman and classical scholar, and her mother was known for her literary achievements. In her teens, Li began to compose poetry, and, over the course of her life, she produced many volumes of essays and poems. Poems to her husband even suggest mutual love and respect and treating her as an equal. In fact, throughout Chinese history, it was not unusual for women to challenge and transgress boundaries. At the highest level, during both the Han and Tang Dynasties, we find cases of empress dowagers dominating youthful heirs to the throne and even one case of an empress declaring her own dynasty.