The ‘Abbasid Caliphate

For many Muslims, ‘Umar II’s reforms had come too late. The Umayyads had already managed to alienate three important groups of Muslims, Kharijis, the mawali, and the Shi‘a, whose combined power and influence were coopted by the ‘Abbasids and threatened the internal security of the caliphate. Kharijis eschewed disputes over lineage and advocated a more egalitarian brand of Islam than the Sunni Umayyads. They believed that any Muslim could be the rightful heir to the mantle of the Prophet, so long as that person rigorously adhered to the examples set forth in the Sunna. Kharijis thought that caliphs who diverged from the Prophet’s example should be overthrown, as evidenced by their assassination of the Caliph ‘Ali. Second, Umayyad authorities had enacted punitive measures against the mawali, mostly Persians, but also Kurds and Turks. They treated them like second-class citizens, no different than the People of the Book. Finally, it angered most of the Shi‘a that the Umayyads could not trace their ancestry to the Prophet Muhammad. They also blamed the Umayyads for the death of their martyr Husayn. The ‘Abbasids collaborated with these disaffected groups to incite unrest and rebellion. They particularly cultivated Shi‘a anti-Umayyad sentiment, emphasizing their own connection to the Prophet; indeed, the ‘Abbasids traced their ancestry to Muhammad’s uncle ‘Abbas and the Hashimite Clan. They also vaguely promised to adopt Shi‘a Islam once in power. Together, these three groups formed a constituency that campaigned on behalf of the ‘Abbasids.

A secretive family, ‘Abbasids bided their time until the opportune moment to rebel against the Umayyad Caliphate. In 743, the ‘Abbasids began their revolution in remote Khorasan, a region in eastern Persia, just as the Umayyads were contending with not only revolts but also the inopportune death of the Caliph Hisham. In that moment of Umayyad disorder, the ‘Abbasids dispatched Abu Muslim, a Persian general, to Khorasan to start the revolution. Abu Muslim’s early victories against the Umayyads allowed Abu al-‘Abbas, leader of the ‘Abbasid dynasty, to enter the sympathetic city of Kufa in 748. Together, Abu Muslim and Abu al-‘Abbas, who adopted the honorific of as-Saffah, or “the generous,” confronted the Umayyad Caliph Marwan II in 750, at the Battle of the Zab, in modern day Iraq. Sensing defeat, Marwan II fled, but his pursuers eventually caught and killed him in Egypt. As-Saffah captured the Umayyad capital of Damascus shortly thereafter. The ‘Abbasids attempted to eliminate the entire house of the Umayyads so that not one remained to come forth and rise up against them, but one, ‘Abd al-Rahman, escaped eminent death and fled to Egypt. The only member of the family to abscond from certain demise, ‘Abd al-Rahman fled across North Africa to Spain, where he recreated a Spanish Muslim dynasty in a parallel fashion to the Umayyad dynasty in Syria. Under the Umayyads, Spain became the wealthiest and most developed part of Europe (see Chapter Seven). In fact, it was through Islamic Spain that ancient Greek learning entered Europe.

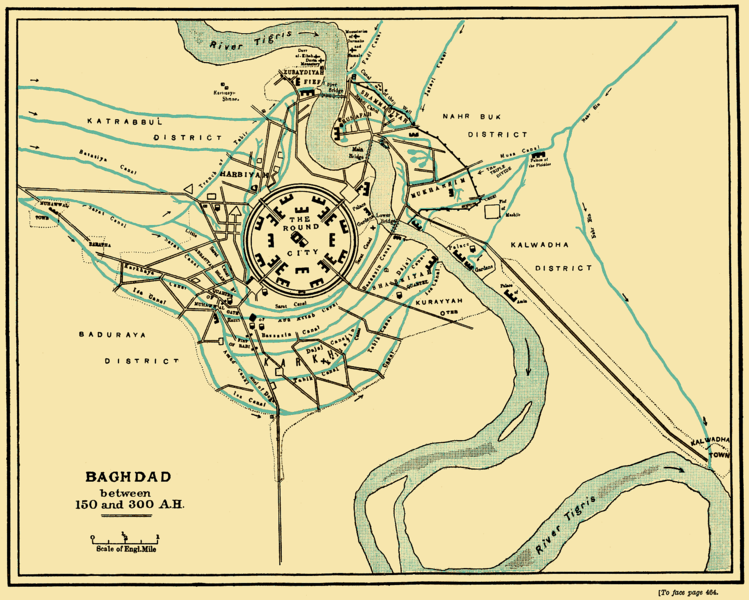

The change from the Umayyad’s Arab tribal aristocracy to a more egalitarian government, one based on the doctrines of Islam, under the ‘Abbasids, corresponds to Ibn Khaldun’s Cyclical Theory of History. The ‘Abbasids officially advocated Sunni orthodoxy and severed their relationship of convenience with the Shi‘a. They even went so far as to assassinate many Shi‘a leaders, whom they regarded as potential threats to their rule. To escape ‘Abbasid persecution and find safety and security, many Shi‘a scattered to the edges of the empire. While the Shi‘a might have been disappointed with the ‘Abbasids for refusing to advocate Shi‘a Islam, most Muslims welcomed the ‘Abbasid’s arrival. They had justified their revolt against the corrupt Umayyads because the latter had digressed from the core principles of Islam. As standard bearers of the Prophet’s own family, the ‘Abbasids were publicly pious, even digging wells and providing protection along hajj routes. Caliph al-Mansur (754 – 775) abandoned the Umayyad capital of Damascus and moved the caliphate close to the old Persian capital of Ctesiphon. Construction of the new city of Baghdad began in 762. Situated at the confluence of the Tigris and Diyala rivers, it boasted a prime location that provided access to the sea with enough distance from the coast to offer safety from pirates. Modeled after circular Persian cities, Baghdad rapidly escaped its confines and expanded into its environs. Quickly eclipsing Chang’an, it became the largest city in the world, with over half a million inhabitants. In effect, Baghdad became a public works project, employing 100,000 citizens and stimulating the economy. Al-Mansur’s newly-founded city proudly displayed lavish ‘Abbasid family residences and grandiose public buildings. It even had working sewers, which dumped raw sewage into the nearby canals and rivers.

Prominently featured in One Thousand and One Nights, Harun al-Rashid (789 – 809) represented the climax of ‘Abbasid rulers; as such, he improved upon the work his predecessors had begun. For example, Harun furthered Baghdad’s development into a major economic center by encouraging trade along the Silk Road and through the waters of the Indian Ocean. He also made marginal agricultural land more productive, taking advantage of technological advances in irrigation to cultivate borrowed crops like rice, cotton, and sugar from India, as well as citrus fruits from China.

Harun al-Rashid’s reign coincided with the so-called Golden Age of Islam when Baghdad developed into a preeminent city of scholarship. He began construction of the Bayt al-Hikmah (House of Wisdom), the foremost intellectual center in the Islamic world. The complex boasted of several schools, astronomical observatories, and even a giant library, where scholars translated scientific and philosophical works from neighboring civilizations, including works from Persian, Hindi, Chinese, and Greek.

As a result of this move from Damascus to Baghdad, Persia increasingly influenced the Islamic world, with a synthesis of Arab and Persian culture beginning under the ‘Abbasids. For instance, the Persian Sibawayah (d. c. 793) responded to the need for non-Arab Muslims to understand the Quran by systematizing the first Arabic grammar, titled al-Kitab. The greatest poet of the period, Abu Nuwas (d. c. 813), was of mixed parentage, Arab and Iranian. The avant-garde themes of his poems often emphasized dissolute behavior. Although ibn Ishaq (d.768), a historian of sorts, was born in Medina, he relocated to Baghdad, where he too came under the influence of Persian culture. At the behest of Caliph al-Mansur, he composed the first authoritative biography of the Prophet Muhammad. Another important Persian scholar, al-Tabari (d. 923) wrote the History of Prophets and Kings, a great resource on early Islamic history.

Inheritors of Sasanian court traditions that emphasized ceremony, the ‘Abbasids slowly distanced themselves from their subjects. The harem embodied this spatial separation. A forbidden place, the caliph’s family made the harem their personal residence. Caliphs controlled the empire through family, solidifying political alliances by marrying many powerful women. The harem bestowed power to women, and they played an important role in influencing ‘Abbasid politics, particularly in terms of questions over succession. In the late ‘Abbasid period, various women selected and trained the successors. Young men who were to rule resided in the harem, and much scheming over which son the caliph preferred occurred there. The mother of the caliph, however, dominated internal politics of the space. Harun’s mother played a significant role in his reign, for example. The second most powerful woman in the household was the mother of the heir apparent. She could be any woman, even a concubine, for young, beautiful women were highly sought after at a time when the harem became more important under the ‘Abbasids.

Riven apart by palace intrigue, the ‘Abbasid Caliphate eventually succumbed to internecine warfare. In fact, Harun al-Rashid himself divided the caliphate when he designated his eldest son, al-Amin, as his heir, for he had already bequeathed the province of Khorasan to his younger son, al-Ma’mun. Upon their father’s death in 809, al-Amin demanded his brother’s territory and obeisance. Of course, al-Ma’mun refused, and a catastrophic civil war ensued. In 812, al- Ma’mun’s army, under the command of his Persian general, Tahir, laid siege to Baghdad. Tahir caught al-Amin attempting to escape from the city and decapitated him. Al-Ma’mun succeeded his brother as caliph, but remained in Merv, his former capital. He ultimately relocated to Baghdad in 819, by which time, years of sporadic violence and lawlessness had severely damaged the city.

Al-Ma’mun (r.813 – 833) continued his father’s tradition of sponsoring scholarship. He completed the Bayt al-Hikmah that his father had begun. He also expressed a love for philosophical and theological debate and encouraged the Islamic doctrine known as the Mu‘tazila, a rationalist formulation of Islam that stressed free will over divine predestination. Influenced by Aristotelian thought, the Mu‘tazila attempted to solve the theological question of evil. It asserted that human reason alone could inform proper behavior. Condemned as a heresy for incorporating extra Islamic patterns of thought into their belief system, many Muslims concluded that the Mu‘tazila’s rationalism exceeded the holy doctrines of Islam.

The ‘Abbasids began their long, slow decline under al-Ma’mun, who was the first caliph to confer greater freedom upon his emirs, or provincial governors, initiating a process of decentralization that eventually unleashed uncontrollable centrifugal forces. This process began when al-Ma’mun first awarded his general Tahir with the governorship of Khorasan, where Tahir raised his own revenue and directed his own affairs. The Tahirid dynasty dominated the politics of the region, resisting Abbasid attempts to restrain them. From Khorasan, Tahir’s family represented an existential threat to the caliphate.

Internal problems continued under al-Mu‘tasim (833 – 842), the successor to al-Ma’mun, who replaced undependable tribal armies with mamluks. The mamluks played an increasingly important role in the fate of the caliphate. They were part of an elite slave system that imported young boys from various backgrounds, though usually Turkic, and trained them in the military arts. Because the enslavement of Muslims was not permitted in Islam, caliphs obtained slaves by raiding outside of the Islamic world or by trading for them. Indoctrinated at a young age, mamluks remained loyal to their leaders, serving as their personal bodyguard. Once emancipated, however, they entered into a contractual relationship with their former masters and benefited from certain property and marriage rights. Although often portrayed as slaves in the popular imagination, mamluks actually formed a proud caste of soldiers who considered themselves superior to the rest of society. As the elite bodyguards to the caliph, they supplanted the tradi- tional ethnic hierarchy of the ‘Abbasids, a shift which led to much class conflict often resulting in unrest and civil disturbances. In order to remove the mamluks from the volatile situation in Baghdad, the caliph moved the capital to Samarra, some 60 miles to the north, a measure that only delayed the inevitable, as subsequent caliphs could not control the rising tensions that resulted in social instability and contributed to the decentralization and fragmentation of the empire.

The transition from tribal armies to mamluks had profound repercussions for the ‘Abbasids. Mamluks like Ahmad ibn Tulun (835 – 884), a slave from Circassia, most exemplified this pattern of decentralization and fragmentation that had disastrous consequences for the ‘Abbasid Caliphate. He had been sent by the ‘Abbasids to Egypt in order to restructure and strengthen it on their behalf. An intellectual and religious person, ibn Tulun founded schools, hospitals, and mosques in Egypt, the most famous being the eponymous ibn Tulun Mosque. However, he saw weakness back in Baghdad, as the ‘Abbasids suffered from instability, including palace intrigue, disorderly mamluks, and revolts like the Zanj Rebellion, a slave rebellion that threatened the fate of the caliphate. The ‘Abbasids could not control ibn Tulun, and, as the caliphate broke down, he managed to secure almost complete autonomy from Baghdad. By the end of his reign, he was so independent that he kept his own tax revenue and raised his own mamluk army, for he, too, depended militarily and politically on his loyal mamluks to stay in power.

Ibn Tulun’s autonomy in Egypt portended the decline of the ‘Abbasids, whose real authority came to an end in 945. The Buyids, an Iranian dynasty, overthrew the ‘Abbasids and relegated them to the status of mere religious figureheads; the caliphate continued in name only. Following the collapse of the Abbasids, the centralization and political unity of the lands formerly under their control broke down; however, economic, cultural, and religious unity remained.