Mesopotamian Empires

Mesopotamian Empires

In the second half of the third millennium BCE, Sumerian city-states fought each other, and dynasties rose and fell. Kings consolidated power over multiple city-states in the region. Then, King Sargon of Akkad enlarged the scale by conquering the Sumerian city-states and parts of Syria, Anatolia, and Elam. In doing so, he created one of the world’s first empires in approximately 2334 BCE. For generations, Mesopotamian literature celebrated the Akkadian Empire (c. 2334 – 2100 BCE) that King Sargon founded. Like the Akkadian Empire, three subsequent empires, the Babylonian Empire (c. 1792 – 1595 BCE), the Assyrian Empire (c. 900 – 612 BCE), and the Neo-Babylonian Empire (c. 605 – 539 BCE), also ruled large parts of Mesopotamia and the Fertile Crescent.

The Akkadian Empire (c. 2334 – 2100 BCE)

Sargon of Akkad founded the first empire in Mesopotamia. Legends about Sargon of Akkad stress that he rose from obscurity to become a famous, powerful king. While the legends all tend to describe him as coming from humble origins and rising to the top using his own wits, there are many variations. One much later Babylonian tablet, from the seventh century BCE, describes his background as descendent of a high priestess and an anonymous father. His mother hid her pregnancy and the birth of Sargon, secreting him away in a wicker basket on a river, where he was rescued and then raised by Aqqi, a water-drawer. This version of the legend links Sargon with a more elite family through his birth-mother, a high priestess, but also shows how he had to advance himself up to king after being adopted by the rather more humble figure of a water-drawer.

From his allegedly humble origins, Sargon of Akkad conquered Sumerian city-states one by one, creating an empire, or a large territory, encompassing numerous states, ruled by a single authority. It’s quite possible that Sargon of Akkad’s predecessor, who claimed to rule over the large region stretching from the Mediterranean Sea to the Persian Gulf, began the process of building the empire, but Sargon is remembered for accomplishing the task. One of the reasons we attribute the empire to him is his use of public monuments. He had statues, stellae (tall, upright pillars), and other monuments built throughout his realm to celebrate his military victories and to build a sense of unity within his empire. Archaeologists have not found the empire’s capital city, Akkad. However, from the available information, archaeologists have estimated its location, placing it to the north of the early Mesopotamian city-states, including Ur and Sumer. It is clear that Sargon of Akkad turned the empire’s capital at Akkad into one of the wealthiest and most powerful cities in the world. According to documentary sources, the city’s splendor stood as another symbol of Sargon’s greatness. The city grew into a cosmopolitan center especially because of its role in trade. Akkadian rulers seized and taxed trade goods, with trade routes extending as far as India. Sargon ruled the empire for over fifty years. His sons, grandson, and great grandson attempted to hold the empire together. After about 200 years, attacks from neighboring peoples caused the empire to fall. After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, Hammurabi founded the next empire in the region in 1792 BCE.

The Babylonian Empire (1792 – 1595 BCE)

Hammurabi, who aspired to follow Sargon’s example, created the next empire in the region, the Babylonian Empire. With well-disciplined foot soldiers armed with copper and bronze weapons, he conquered Mesopotamian city-states, including Akkad and Sumer, to create an empire with its capital at Babylon. Although he had other achievements, Hammurabi is most famous for the law code etched into a stele that bears his name, the Stele of Hammurabi.

The Stele of Hammurabi records a comprehensive set of laws. Codes of law existed prior to Hammurabi’s famous stele, but Hammurabi’s Code gets a lot of attention because it is still intact and has proven very influential. As seen in Figure 2.5, the upper part of the stele depicts Hammurabi standing in front of the Babylonian god of justice, from whom Hammurabi derives his power and legitimacy. The lower portion of the stele contains the collection of 282 laws. One particularly influential principle in the code is the law of retaliation, which demands “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” The code listed offenses and their punishments, which often varied by social class. While symbolizing the power of the King Hammurabi and associating him with justice, the code of law also attempted to unify people within the empire and establish common standards for acceptable behavior. An excerpt of Hammurabi’s Code appears below:

6. If anyone steal the property of a temple or of the court, he shall be put to death, and also the one who receives the stolen thing from him shall be put to death.

8. If any one steal cattle or sheep, or an ass, or a pig or a goat, if it belong to a god or to the court, the thief shall pay thirtyfold therefore; if they belonged to a freed man of the king he shall pay tenfold; if the thief has nothing with which to pay he shall be put to death.

15. If any one receive into his house a runaway male or female slave of the court, or of a freedman, and does not bring it out at the public proclamation of the major domus, the master of the house shall be put to death.

53. If any one be too lazy to keep his dam in proper condition, and does not so keep it; if then the dam break and all the fields be flooded, then shall he in whose dam the break occurred be sold for money, and the money shall replace the corn which he has caused to be ruined.

108. If a tavern-keeper (feminine) does not accept corn according to gross weight in payment of drink, but takes money, and the price of the drink is less than that of the corn, she shall be convicted and thrown into the water.

110. If a “sister of god” open a tavern, or enter a tavern to drink, then shall this woman be burned to death.

127. If any one “point the finger” (slander) at a sister of a god or the wife of any one, and can not prove it, this man shall be taken before the judges and his brow shall be marked. (by cutting the skin or perhaps hair)

129. If a man’s wife be surprised (in flagrante delicto) with another man, both shall be tied and thrown into the water, but the husband may pardon his wife and the king his slaves.

137. If a man wish to separate from a woman who has borne him children, or from his wife who has borne him children: then he shall give that wife her dowry, and a part of the usufruct of field, garden, and property, so that she can rear her children. When she has brought up her children, a portion of all that is given to the children, equal as that of one son, shall be given to her. She may then marry the man of her heart.

195. If a son strike his father, his hands shall be hewn off.

196. If a man put out the eye of another man his eye shall be put out. (An eye for an eye)

197. If he break another man’s bone, his bone shall be broken.

198. If he put out the eye of a freed man, or break the bone of a freed man, he shall pay one gold mina.

199. If he put out the eye of a man’s slave, or break the bone of a man’s slave, he shall pay one-half of its value.

202. If any one strike the body of a man higher in rank than he, he shall receive sixty blows with an ox-whip in public.

203. If a free-born man strike the body of another free-born man or equal rank, he shall pay one gold mina.

205. If the slave of a freed man strike the body of a freed man, his ear shall be cut off[1]

Hammurabi also improved infrastructure, promoted trade, employed effective administrative practices, and supported productive agriculture. For example, he sponsored the building of roads and the creation of a postal service. He also maintained irrigation canals and facilitated trade all along the Persian Gulf. After Hammurabi’s death, his successors lost territory. The empire declined, shrinking in size. The Hittites, from Anatolia, eventually sacked the city of Babylon in 1595 BCE, bringing about the official end of the Babylonian Empire.

The Assyrian Empire (c. 900 – 612 BCE)

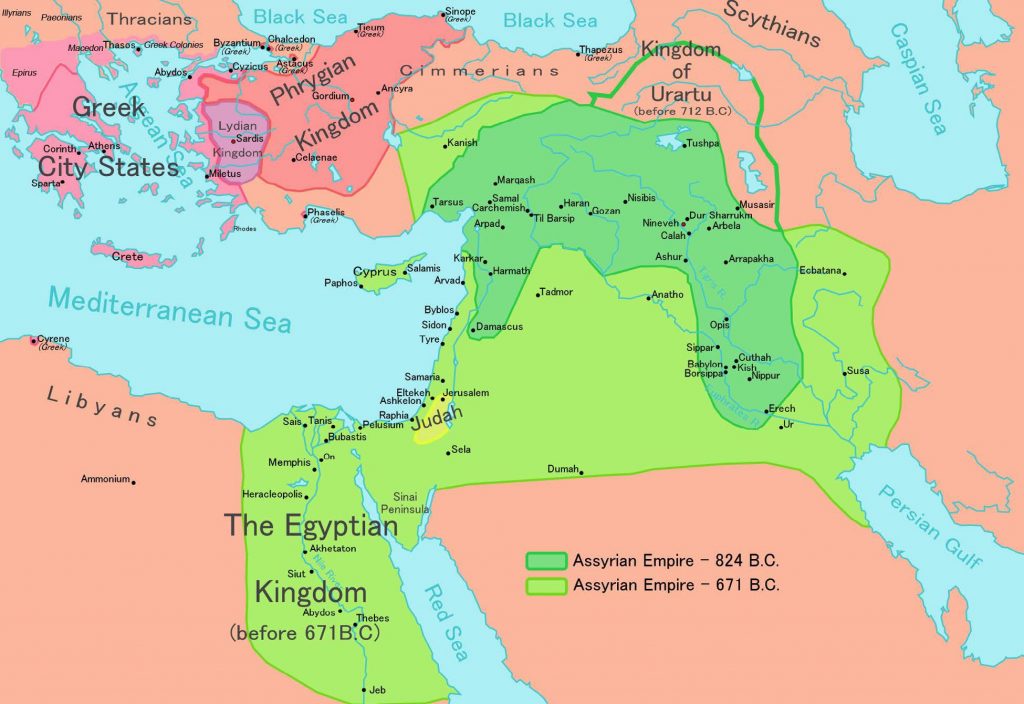

The Assyrian Empire, which saw its height of power at the end of the first millennium to the seventh century BCE, was larger than any empire that preceded it.

Dominating the region, its well-equipped soldiers used their stronger iron weapons to extend the empire’s control through Mesopotamia, Syria, parts of Anatolia, Palestine, and up the Nile into Egypt. They used siege warfare, along with battering rams, tunnels, and moveable towers, to get past the defenses of cities. The Assyrians had a large army (with perhaps as many as 150,000 soldiers) that utilized a core of infantry, a cavalry, as well as chariots. As part of their military strategy, the Assyrians purposefully tried to inspire fear in their enemies; they decapitated conquered kings, burnt cities to the ground, destroyed crops, and dismembered defeated enemy soldiers. One Assyrian soldier claimed:

In strife and conflict I besieged [and] conquered the city. I felled 3,000 of their fighting men with the sword…I captured many troops alive: I cut off of some of their arms [and] hands; I cut off of others their noses, ears, [and] extremities. I gouged out the eyes of many troops. I made one pile of the living [and] one of heads. I hung their heads on trees around the city.[2]

The Assyrians expected these methods to deter potential rebellions and used their spoils of war, like precious metals and livestock, to finance further military campaigns. After conquering an area, they conscripted men into their army, and employed resettlement and deportation as techniques to get laborers where they wanted them and deal with communities who opposed their regime. They also collected annual tributes that were apparently high enough to, at least occasionally, spur rebellions despite the Assyrians’ reputation for violent retribution.

In addition to its military strength, the Assyrian empire also stands out for the size of its cities and its administrative developments. The empire’s biggest cities, such as Nineveh and Assur, each had several million people living within them. Administratively, kings ruled Assyria, appointing governors to oversee provinces and delegates to keep tabs on the leaders of allied states. There were between 100 and 150 governors, delegates, and top officials entrusted by the king with ruling in his place and helping him maintain the empire. In the later centuries of the Assyrian Empire, kings chose these officials on the basis of merit and loyalty. Kings met with large groups of officials for rituals, festivals, and military campaigns. Evidence of such meetings has led some scholars to propose the possibility that the king and his officials might have worked together in something resembling a parliamentary system, though there is no scholarly consensus on the point. Ultimately, the Assyrian Empire became too large to control; rebellions occurred with more frequency and were difficult for its overextended military to quell. The empire fell after the conquest of Nineveh in 612 BCE.

The New Babylonian Empire (c. 626 – 539 BCE)

With the weakening of the Assyrian Empire, the New Babylonian Empire began to dominate Mesopotamia. Lasting for less than 100 years, the New Babylonian Empire is best known for its ruler, Nebuchadnezzar II, and its great architectural projects. As described in the Hebrew Scriptures (also known as the Old Testament), Nebuchadnezzar II, who ruled from 605 – 562 BCE, was a ruthless leader. He gained notoriety for destroying the city of Jerusalem and deporting many of the city’s Jews to Babylon. The captive Jews suffered in exile, as they were not allowed to return to their homeland. Nebuchadnezzar II also rebuilt Babylon with fortresses, temples, and enormous palaces. He associated the New Babylonian Empire with the glory of ancient Babylonia by reviving elements of Sumerian and Akkadian culture. For example, he had artists restore ancient artwork and celebrated the kings of old, like Hammurabi. Nebuchadnezzar is often also credited with rebuilding the city’s ziggurat, Etemanaki, or the “Temple of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth.” When completed, the ziggurat rose several stories above the city and seemed to reach to the heavens. Some scholars claim that the Babylonian ziggurat was the famous Tower of Babel described in the Old Testament. Another one of Nebuchadnezzar’s purported projects, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, was considered by the later Greek historian Herodotus to be one of the Seven Wonders of the World. According to legend, Nebuchadnezzar had the hanging gardens built for his wife. He made the desert bloom to remind her of her distant homeland; the elaborate gardens planted on rooftops and terraces were designed so that the plants’ leaves would spill down high walls. Since definitive archaeological evidence of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon has not been found, scholars continue to debate its most likely location and even its very existence. After the death of Nebuchadnezzar II, outside military pressures as well as internal conflict weakened the empire until the much larger Persian Empire conquered the New Babylonian Empire in 539 BCE.

- Enter yo4 “The Code of Hammurabi, c. 1780 BCE.” Ancient History Sourcebook. Fordham University. https://legacy.fordham.edu/ halsall/ancient/hamcode.asp#textur footnote content here. ↵

- 5 Quoted in Erika Belibtreau, “Grisly Assyrian Record of Torture and Death,” http://faculty.uml.edu/ethan_Spanier/ Teaching/documents/CP6.0AssyrianTorture.pdf ↵