Carolingian Collapse

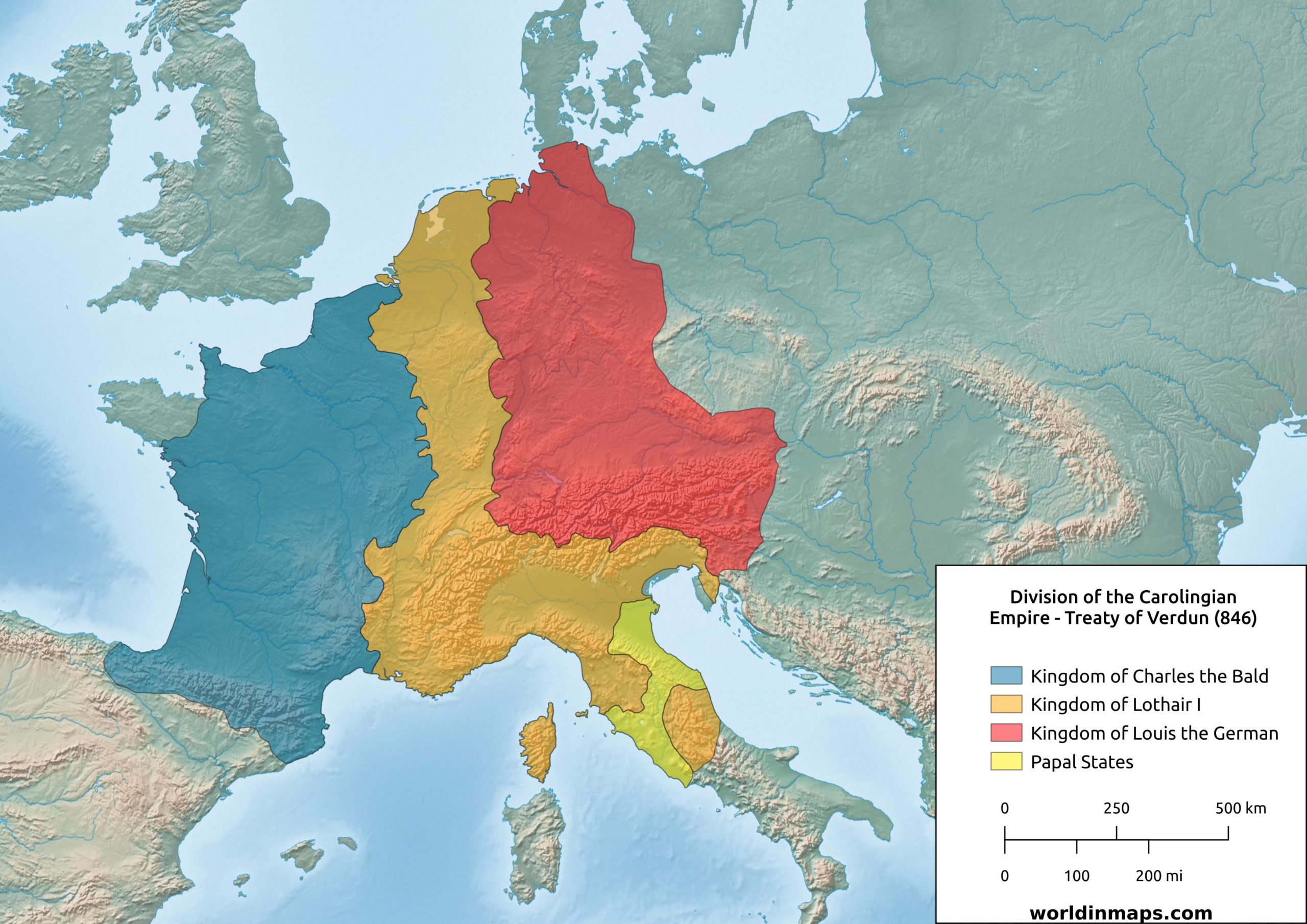

Charlemagne’s efforts to create a unified empire did not long outlast Charlemagne himself. His son, Louis the Pious (r. 814 – 840), succeeded him as emperor. Louis continued Charlemagne’s project of Church reform; unlike Charlemagne, who had had only one son to survive into adulthood, Louis had three. In addition, his eldest, Lothar, had already rebelled against him in the 830s. When Louis died, Lothar went to war with Louis’s other two sons, Charles the Bald and Louis the German. This civil war proved to be inconclusive, and, at the 843 Treaty of Verdun, the Carolingian Empire was divided among the brothers. Charles the Bald took the lands in the west of the Empire, which would go on to be known first as West Francia and then, eventually, France. To the East, the largely German-speaking region of Saxony and Bavaria went to Louis the German. Lothar, although he had received the title of emperor, received only northern Italy and the land between Charles’s and Louis’s kingdoms.

This division of a kingdom was not unusual for the Franks—but it meant that there would be no restoration of a unified Empire in the West, although both the king of Francia and the rulers of Central Europe would each claim to be Charlemagne’s successors.

Western Europe faced worse problems than civil war between the descendants of Charlemagne. In the centuries following the rise of the post-Roman Germanic kingdoms, Western Europe had suffered comparatively few invasions. The ninth and tenth centuries, by contrast, would be an “age of invasions.”

In the north of Europe, in the region known as Scandinavia, a people called the Norse had lived for centuries before. These were Germanic peoples, but one whose culture was not assimilated to the post-Roman world of the Carolingian west. They were still pagan and had a culture that, like that of other Germanic peoples, was quite warlike. Their population had increased; additionally, Norse kings tended to exile defeated enemies. These Norsemen would often take up raiding other peoples, and when they took up this activity, they were known as Vikings.

One factor that allowed Norse raids on Western Europe was an improvement in their construction of ships. Their ships were long, flexible, and also had a shallow enough draft that they did not need harbors so could be pulled up along any beach. Moreover, they were also shallow enough of draft that they could sail up rivers for hundreds of miles. What this feature of these ships meant was that Norse Vikings could strike at many different regions, often with very little warning.

Even more significant for the Norse attacks was that Western Europe in the ninth and tenth centuries was made up of weak states. The three successor kingdoms to Charlemagne’s empire were often split by civil war. Although King Charles the Bald (r. 843 – 877) enjoyed some successes against the Vikings, his realm in general was subject to frequent raids. England’s small kingdoms were particularly vulnerable. From 793, England had suffered numerous Viking raids, and these raids increased in size and scope over the ninth century. Likewise, to the west, Ireland, with its chiefs and petty kings, lacked the organization of a state necessary to deal with sustained incursions.

The result was that not only did Viking raids on the British Isles increase in scope and intensity over the ninth century, but also the Norse eventually came to take lands and settle.

To the south and west, al-Andalus suffered fewer Norse attacks than did the rest of Europe. A sophisticated, organized state with a regular army and a network of fortresses, it was able to effectively deal with raiders. The Spanish emir Abd-al Rahman II defeated a Viking raid and sent the Moroccan ambassador the severed heads of 200 Vikings to show how successful he had been in defending against them.

To the east, the Norse sailed along the rivers that stretched through the forests and steppes of the area that today makes up Russia and Ukraine. The Slavic peoples living there had a comparatively weak social organization, so in many instances they fell under Norse domination. The Norsemen Rurik and Oleg were said to have established themselves as rulers of Slavic peoples as well as the princedoms of Novgorod and Kiev, respectively, in the ninth century. These kingdoms of Slavic subjects and Norse masters became known as the Rus.

Further to the south, the Norse would often move their ships over land between rivers until finally reaching the Black Sea and thus Constantinople and Byzantium. Although on occasion a Norse raid would have great success against Byzantine forces, in general, a powerful and organized state meant that, as with al-Andalus, the Norse encountered less success.

Norse invaders were not the only threat faced by Western Europe. As the emirs of Muslim North Africa gradually broke away from the centralized rule of the Abbasid Caliphate (see Chapter Eight), these emirs, particularly those of Tunisia, what is today Algeria, and Morocco turned to legitimate themselves by raid and plunder; this aggression was often directed at southern Francia and Italy. The Aghlabid emirs in particular not only seized control of Sicily, but also sacked the city of Rome itself in 846. North African raiders would often seize territory on the coasts of Southern Europe and raid European shipping in order to increase their own control of trade and commerce. In addition, the emirs of these North African states would use the plunder from their attacks to reward followers, in another example of the pillage and gift system.

Central Europe also faced attacks, these from the Magyars, a steppe people. The Magyars had been forced out of Southeastern Europe by another steppe people, the Pechenegs, and so from 899 on migrated into Central Europe, threatening the integrity of East Francia. As was the case with other steppe peoples, their raids on horseback targeted people in small unfortified communi- ties, avoiding larger settlements. They eventually settled in the plains of Eastern Europe to found the state of Hungary; although they made Hungary their primary location, they nevertheless continued to raid East Francia through the first part of the tenth century.

An Age of Invasions in Perspective

Norse, Magyar, and Muslim attacks on Europe wrought incredible damage. Thousands died, and tens of thousands more were captured and sold into slavery in the great slave markets of North Africa and the Kievan Rus. These raids furthered the breakdown of public order in Western Europe. But these raids had effects that also brought long-term benefits. Both Norse and Muslim pirates traded just as much as they raided. Indeed, even the plunder of churches and selling of the gold and silver helped create new trade networks in both the North Sea and Mediterranean. These new trade networks, especially where the Norse had established settlements in places like Ireland, gradually brought about an increase in economic activity.

All told, we should remember this “age of invasions” in terms both of its human cost and of the economic growth it brought about.

New States in Response to Invasions

In response to the invasions that Europe faced, newer, stronger states came into being in the British Isles and in Central Europe. In England, Norse invasions had destroyed all but one of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The only remaining kingdom was Wessex. Its king, Alfred the Great (r. 871 – 899), was able to stop Norse incursions by raising an army and navy financed by a kingdom-wide tax. This tax, known as the geld, was also used to finance the construction of a network of fortresses along the frontier of those parts of England still controlled by the Norse. This new system of tax collection would eventually mean that England, a small island on the periphery, would eventually have the most sophisticated bureaucracy in Western Europe (although we must note that in comparison with a Middle Eastern or East Asian state, this bureaucracy would be considered rudimentary and primitive).

Likewise, in Central Europe, the kings of East Francia, the region made up of those Saxon territories the Carolingians had conquered in the eighth century as well as various peoples to the south and east, gradually built a kingdom capable of dealing with Magyar invaders. Henry the Fowler (r. 919 – 936) took control of East Francia after the end of the Carolingian Dynasty. He was succeeded by Otto the Great (r. 936 – 973), whose creation of a state was partially the result of luck: his territory contained large silver mines that allowed him to finance an army. This army was able to decisively defeat the Magyar raiders and also allow these kings to expand their power to the east, subjugating the Slavic peoples living in the forests of Eastern Europe.