1 Navigating the New Frontier of Generative AI in Peer Review and Academic Writing

Chris Mayer

Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of the current landscape and implications of Generative AI (GenAI) in higher education, particularly focusing on its role in academic writing and peer review. The emergence of GenAI tools such as ChatGPT is a transformative development in education, with widespread adoption at unprecedented speed. Large Language Models such as ChatGPT offer great potential for enhancing education and academic writing but also raise serious ethical concerns and tensions including access and usability, the perpetuation of Standard Academic English, and issues of linguistic justice. There is also the need for new approaches and pedagogies for how to ethically and effectively capitalize on this technology. Peer review has many benefits but can also be a source of anxiety and frustration for both teachers and students. The chapter discusses these issues and then offers an approach and lesson plans built around ChatGPT and John Bean’s hierarchy for error correction to guide in-class peer review in a first year writing class, as well as suggestions for how GenAI might be used for other disciplinary writing.

Keywords: Generative AI, academic writing, peer review, ethical considerations, pedagogical strategies

Introduction

The age of Skynet is on the horizon (or for the less cynical, the age of AI sentience). In less than two years, Generative AI has already begun reshaping the landscape of learning and evaluation. Sid Dobrin, a leading scholar on the intersections of writing and technology, writes that Generative AI (GenAI) is “now inextricably part of how students will write in the academy and beyond” (2023, p. 20). Indeed. In a survey of Canadian university students, more than half (52%) reported using GenAI in their schoolwork, and 87% agreed the quality of their work improved as a result of GenAI (KMPG, 2023). Another survey of 2000 US college students conducted in March and April of 2023 shows that 51% would continue using GenAI even if their schools or instructors prohibit their use (NeJame et al., 2023). This data strongly suggests GenAI adoption has already achieved critical mass. It is easy to see that “Higher education is beyond the point of no return” (NeJame et al., 2023).

As educators, we cannot ignore what is happening. Besides, universities are increasingly seen as preparing students for the workplace and AI will necessarily become part of that preparation. According to Stanford’s Artificial Intelligence Index Report, 34% of all industries were using AI for at least one function in their business in 2022 (Maslej et al., 2023). The number today is almost certainly higher.

In response to Dobrin’s question about whether GenAI heralds a “new phase of feedback to student writing processes” (2023, p. 21), I believe the answer is a resounding yes! It is widely known that feedback has a strong effect on student achievement and outcomes, including their motivation and self-efficacy (e.g., Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Wisniewski et al., 2019). However, providing feedback is time consuming and costly to provide whereas GenAI can do it nearly instantaneously. It has already been used for some years in computer science to provide formative feedback which students have found effective and useful (for instance, see Metz, 2021). Now with increasingly sophisticated language models, GenAI can be leveraged to give feedback to written essays outside the context of programming or simple (yet controversial) scoring of SAT essays.

In fact, GenAI even shows promise in providing formative feedback to instructors themselves. For instance, an AI tool called M-Powering Teachers was used to give teachers feedback on the feedback they gave students, specifically regarding the teachers’ uptake of student writing in their comments (uptake includes recasting a student’s idea and then framing a question aimed to generate more thinking, development, or perspectives). In their study, Demszky et al. (2023) found feedback offered by M-Powering Teachers increased the rate of uptake in instructors’ feedback to students. This increased the likelihood students would complete subsequent assignments and thus may be directly linked to student motivation.

GenAI will impact education on all fronts, from teacher to student, to pedagogy, approach, and more. Sooner rather than later, educators must adjust their pedagogies and policies in response to this transformative technology, for both their own good and their students’. To that end, this chapter introduces and discusses possibilities and tensions GenAI presents for academic writing and offers a two part lesson for using GenAI for in-class peer review.

Standard Academic English and GenAI

On the surface, GenAI tools like ChatGPT might seem like an easy answer to democratize access to linguistic resources. They have the potential to guide students in navigating Standard Academic English (SAE), especially for socio and linguistically marginalized students who may otherwise face penalties in traditional settings. However, it’s essential to approach the technology with caution. These tools can both empower and marginalize, a conundrum Warschauer et al. (2023) describe as the “rich get richer” contradiction. The digital divide remains real and for many underprivileged students, technological access and savviness remain barriers to entry (e.g., Dobrin, 2023; Horner et al., 2011). This speaks to the need for teachers to teach students how to use GenAI, including how to expertly prompt it to generate a particular kind and quality of content. Warschauer et al. (2023) compare using GenAI to search engines inputs, likening the prompt and results of poorly executed searches to “garbage in, garbage out” (p. 4). Therefore, as we integrate AI into our pedagogical toolkit, it is incumbent upon educators to not only teach students how to effectively utilize GenAI, but also to foster classroom environments where linguistic differences are celebrated, not just tolerated, and where every student’s voice finds a home.

In this light, tools like ChatGPT raise a critical question: do they merely replicate and perpetuate the dominance of SAE, or can they pave the way for a more inclusive and equitable pedagogical environment? Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT come with implicit biases which are ingrained from the data they are trained on. When tasked with academic writing, GenAI generates responses through replicating linguistic features characteristic of academic writing based on statistical likelihoods derived from their training data. In short, when prompted to produce or evaluate academic writing, it generates the most statistically “standard” version of academic writing from its training corpora and thus inadvertently reinforces SAE as the norm.

It is not the fault of GenAI, for academic institutions themselves and the peer-reviewed journals they oversee are the are arbiters and gatekeepers who determine what is worthy of being published, and they more or less continue to uphold SAE as the expected norm both locally and globally (e.g., Flowerdew, 2015). These biases, as Canagarajah (2013) notes, perpetuate the primacy of SAE and sideline the rich variety of Englishes that emerge from diverse racial and cultural milieus. This imposition of homogeneity of academic discourse is further complicated by Hyland (2003), who highlights its varied practices across disciplines.

However, the implications extend beyond linguistic practice. Writing is an embodied activity, deeply intertwined with our identities, emotions, motivations, and lived experiences. In his seminal work, Asao Inoue (2015) argues that traditional grading practices can inadvertently perpetuate linguistic racism, where students’ racial and linguistic identities can be marginalized or undervalued. This not only impacts students’ motivation and emotional well-being, but also brings to the fore issues of equity and fairness in academic assessment. To mitigate these challenges, Inoue suggests labor-based grading contracts, focusing on the effort and process of writing rather than strict adherence to normative linguistic standards like SAE.

As Inoue (2015) and Baker-Bell (2020) argue and show, writing is deeply embodied and personal. Traditional grading methods, often predicated on SAE linguistic standards, overlook these personal dimensions, rendering linguistic non-conformity as a deficit which writers may then project onto themselves and internalize. Thus, the emergence of alternative grading strategies, such as contract grading and labor-based grading, offer a more inclusive lens by emphasizing student evolution over fixed standards (Inoue, 2014).

SAE has long been a cornerstone of academic writing conventions, establishing a uniform standard against which student work is often judged. However, scholars such as Canagarajah (1997), Horner et al. (2011), and McIntosh et al. (2017) have argued for a translingual approach, emphasizing the value of multiple Englishes and the rich linguistic diversity they bring to academic discourses. Yet this creates tensions, particularly as students navigate the constraints of disciplinary writing conventions that are generally unaccommodating of linguistic diversity.

If that were not enough, peer review, particularly for first year writing students, involves navigating a complex emotional landscape and may be fraught with uncertainty about how to leave useful feedback (and indeed, about whether one is even capable of providing it). Students may also be skeptical of their peers’ expertise and ability to provide good feedback: some of the most frequent student complaints about peer review feedback are that it is too congratulatory, broad, and not specific and actionable enough to be of much help (Ferris, 2018; Ferris & Hedgcock, 2023). Others report that peer review exacerbates students’ fears and leaves teachers feeling drained after they see their students’ discomfort and rather limited and not particularly helpful comments after a peer review session (Shwetz & Assif, 2023). This is why many scholars, including Ferris and Hedgcock (2023) and Shwetz and Assif (2023) discuss the importance of framing, discussing, and modeling the peer review process, noting that it can help to defuse anxiety around the peer review process, even for students who are well acclimated to peer review.

In fact, this anxiety is not limited to students. Even teachers (especially new ones) face anxiety about providing feedback to their students. They may question their ability to offer constructive, clear and concise explanations and worry about being too directive and inadvertently appropriating their students’ texts (Ferris et al., 2011; Ferris & Hedgcock, 2023).

The emotional neutrality of a machine-based augmented peer review using ChatGPT could mitigate some of the anxiety-inducing elements of a human-to-human peer review, particularly in an academic context where one’s writing quality will be judged and grades are at stake. This could be particularly advantageous for introverted students and those who may feel intimidated by the peer review process, including non-native speakers and those who do not speak standard or mainstream varieties of English. This does not at all mean we should strip the human element out of peer review! The lack of emotional engagement in a ChatGPT aided peer review could also be a limitation because emotions play a crucial role in shaping the learning experience (Turner, 2023). Despite a lack of empirical evidence, it seems reasonable that using ChatGPT for peer review should be approached and taught as a complementary tool rather than a replacement for human interaction.

Taken together, leveraging GenAI alongside the use of alternative grading approaches – or at the least, with attention to the biases inherent in SAE – may help to reveal and allow us to decenter some of the SAE expectations of academia even as it perpetuates and reinforces those standards. LLMs like ChatGPT offer a potential solution to some of these challenges by assisting students in refining their writing or offering suggestions that align more closely with SAE, potentially leveling the playing field for socio and linguistically marginalized students. Conversely, it can draw students’ attention to linguistic and structural features of SAE so that they can make more informed decisions regarding the extent to which they choose to conform (or not) to SAE expectations.

Of course, we cannot blindly adopt these technologies as there may be insidious and powerful repercussions if they are used and accepted without caution and consideration. Thus, educators need to facilitate discussions on linguistic diversity in order to promote inclusive classroom environments, perhaps ideally through exploring alternative assessment methods that value and honor students’ varied linguistic backgrounds. It’s crucial to recognize that not all students have equal access to or familiarity with such technologies, which can further exacerbate disparities. That is why it is so important to teach students how to wield this potentially transformative technology with expertise. With that in mind, the final section of this chapter offers an approach and lesson plans to introduce ChatGPT into the classroom for in-class peer review.

Peer Review, GenAI, and Bean’s Hierarchy for Error Correction

The introduction of GenAI has profound implications for education, particularly those of ethics regarding labor and source attribution. For the purposes of doing peer review, this chapter assumes that students have produced their own writing or have appropriately attributed GenAI in their writing. This ameliorates many (but certainly not all!) ethical concerns with using AI in the classroom.

The appendices include Bean’s hierarchy for error correction (Appendix 1) and two sequential lessons: first, to introduce students to peer review augmented by ChatGPT (Appendix 2) and second, a lesson for conducting the actual peer review (Appendix 3). There are also language suggestions for how students can prompt the AI during the peer review (Appendix 4) and finally, there is a reflective writing prompt for after the peer review (Appendix 5).

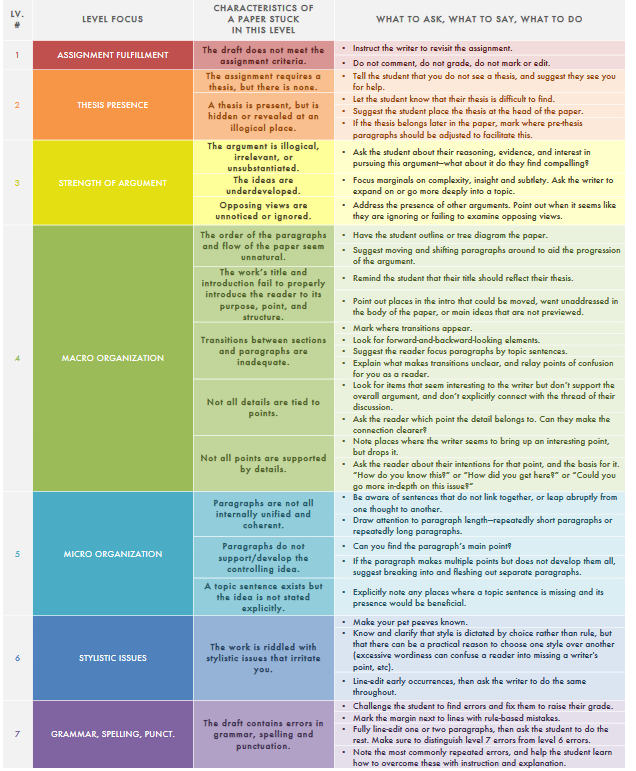

The lessons approach peer review through Bean’s hierarchy for error correction (2011; see Appendix 1) to help structure and modulate an approach to editing and revising that places emphasis on higher order concerns over lower ones. Higher order concerns are foundational elements of a text like the main ideas, purpose, and overall organization while lower order concerns are generally more local in nature, such as grammar or spelling. Bean’s hierarchy categorizes errors into levels on a continuum from higher to lower:

- Higher Order Concerns (HOCs): These relate to fulfillment of the assignment itself, the paper’s main ideas, thesis, organization, and development.

- Middle Order Concerns (MOCs): Here, the focus is on issues like paragraph development, topic sentences, and clarity of ideas.

- Lower Order Concerns (LOCs): These are sentence-level errors, including grammar, punctuation, spelling, and syntax.

The idea is to address HOCs first, MOCs next, and finally, LOCs, ensuring that the author’s foundation is solid before digging into the nitty-gritty details. For a useful illustration of Bean’s hierarchy, see Appendix 1, taken directly from Concordia University.

The two lessons are designed to help students leverage GenAI (specifically ChatGPT 3.5, which is free and open access) during peer review using a generic “argument paper”, as it is one of the common “mutt genres” assigned to students in first year composition (Wardle, 2009). However, the lessons can be adapted to fit most, if not all, genres of writing assigned in FYC and for peer review in other courses.

The first lesson (Appendix 2) aims to introduce ChatGPT as a tool to augment traditional peer review methods. Students are taught how to use ChatGPT interfaces and apply tailored prompts based on Bean’s hierarchy to get feedback. The second lesson (Appendix 3) applies these newly acquired skills in a ChatGPT-assisted peer review session. By the end of these two sessions, students will not only be familiar with GenAI’s potential in reviewing and fine-tuning academic writing but will also be better equipped to offer constructive, nuanced feedback on their peers’ drafts. Critically, they will also get experience comparing their own thoughts and responses to what ChatGPT offers and reflecting on the process of using the technology (see Appendix 5).

How to Process and Share ChatGPT’s Feedback – Framing for the Classroom

When students offer feedback to peers, stress the importance of combining both human insights and ChatGPT’s analytical prowess – make it clear that while ChatGPT offers speed and consistency, it’s not a replacement for human intuition and understanding. Feedback should be specific, actionable, constructive, and kind. Encourage or even require students to not only identify issues but also offer solutions.

To help emphasize the subjectivity of writing and the possibility that what appears to be an error could be a stylistic choice, ask students to make note of instances where they disagree with the GenAI. Come prepared to class with your own examples to share. This is an excellent opportunity to discuss features of SAE as they relate to linguistic justice and notions of “right” and “wrong” in disciplinary academic writing.

Beyond First Year Writing: AI in Other Disciplines

While this chapter focuses on enhancing the peer-review process within first-year writing courses, the utility of GenAI extends to myriad academic disciplines. Consider the following examples:

Sciences: AI can assist in evaluating lab reports by scrutinizing the clarity and completeness of the hypothesis, methodology, and results sections. It can check for logical consistency, factual accuracy, and whether the conclusion aligns with the data presented.

Mathematics and Computer Science: It could be utilized to assess learners’ problem-solving techniques and the logic of underlying proofs. Gen AI can offer step-by-step feedback, providing students with insights into more efficient solutions to problems, and can even be set to take on a dialogic approach when offering feedback. The AI can flag errors in calculations, offer alternate approaches, and challenge students with extension questions to deepen their understanding.

Social Sciences: It could help evaluate the rigor of research methodologies, assess the validity and reliability of survey instruments and interview protocols, and help in coding qualitative data (including helping with cleaning up transcripts). It could also perform sentiment analysis of qualitative data or perform initial statistical analyses of quantitative data as well as write code for software such as R. Furthermore, the AI system can assist in reviewing academic papers for logical flow, coherence, and citation accuracy, thereby enhancing the quality of scholarly publications in the social sciences.

In general, if there are clearly defined evaluation criteria and the writing belongs to a well-established genre, GenAI can likely provide insightful, consistent, and rapid feedback.

Conclusion

GenAI heralds a transformative era in education. This chapter reviewed some of the relationships and emerging tensions between Large Language Models such as ChatGPT and Standard Academic English, particularly within the context of classroom peer review. This technology’s potential to help students with their academic writing is undeniable and it could even democratize access to linguistic resources. At the same time its use risks erasing and further marginalizing non-standard forms of English. It also heightens the need to pay heed to the digital divide and raises pedagogical and curricular questions about how to best equip and prepare students to use this technology effectively. Educators must approach this technology with care and caution, and foster discussion with students about the contradictory tensions inherent in using ChatGPT for peer review, writing, and more. In particular, students should be taught how to use it effectively and responsibly in a way that balances human insight and diversity with the technology’s capability.

Bean’s systematic approach to error correction offers a framework from which to approach the use of GenAI in peer review that could encourage more targeted, thorough, and effective feedback while also helping students (and the GenAI) keep the focus on fundamental, higher order concerns. GenAI augmented peer review holds great potential for more consistent, in-depth, and rapid peer review that cater to the individual needs of students while also addressing concerns and complaints students have about peer review, ranging from anxiety to feelings that the feedback is unhelpful. However, as we step into this new frontier, it is crucial for both instructors and students to proceed with a mix of enthusiasm and prudence to ensure we remain cognizant of, and appreciate, the rich tapestry of linguistic diversity in our classrooms.

Questions to Guide Reflection and Discussion

- How does generative AI reshape the dynamics of peer review in academic writing?

- Reflect on the ethical considerations involved in using AI for academic research and writing.

- Discuss the potential benefits and drawbacks of integrating AI tools in the peer review process.

- How can educators ensure the maintenance of academic integrity in an era of rapidly advancing AI technology?

- In what ways might AI influence the future of academic scholarship and publication standards?

References

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge.

Bean, J. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Canagarajah, S. (2013). Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Routledge.

Demszky, D., Liu, J., Hill, H. C., Jurafsky, D., & Piech, C. (2023). Can automated feedback improve teachers’ uptake of student ideas? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in a large-scale online course. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737231169270

Dobrin, S. I. (2023). Talking about generative AI: A guide for educators (Version 1.0) [Ebook]. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. https://files.broadviewpress.com/sites/uploads/sites/173/2023/05/Talking-about-Generative-AI-Sidney-I.-Dobrin-Version-1.0.pdf

Ferris, D. R. (2018). “They said I have a lot to learn”: How teacher feedback influences advanced university students’ views of writing. Journal of Response to Writing, 4(2), 4-33. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/journalrw/vol4/iss2/2

Ferris, D. R., Brown, J., Liu, H., & Stine, M. E. A. (2011). Responding to L2 students in college writing classes: Teacher perspectives. TESOL Quarterly, 45(2), 207-234. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41307629

Ferris, D. R., & Hedgcock, J. S. (2023). Teaching L2 composition: Purpose, process, and practice (4th ed.). Routledge.

Flowerdew, J. (2015). Some thoughts on English for research publication purposes (ERPP) and related issues. Language Teaching, 48(2), 250–262. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444812000523

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Horner, B., Lu, M. Z., Royster, J. J., & Trimbur, J. (2011). Opinion: Language difference in writing: Toward a translingual approach. College English, 73(3), 303-321.

Hyland, K. (2003). Second language writing. Cambridge University Press.

Inoue, A. B. (2014). Theorizing failure in U.S. writing assessments. Research in the Teaching of English, 48(3), 330-352. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24398682

Inoue, A. B. (2015). Antiracist writing assessment ecologies: Teaching and assessing writing for a socially just future. WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/perspectives/inoue/

KPMG. (2023, August 30). Despite popularity, six in 10 students consider generative AI cheating.https://kpmg.com/ca/en/home/media/press-releases/2023/08/six-in-ten-students-consider-generative-ai-cheating.html

Maslej, N., Fattorini, L., Brynjolfsson, E., Etchemendy, J., Ligett, K., Lyons, T., Manyika, J., Ngo, H., Niebles, J. C., Parli, V., Shoham, Y., Wald, R., Clark, J., & Perrault, R. (2023). The AI index 2023 annual report. AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University. https://aiindex.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/HAI_AI-Index-Report_2023.pdf

McIntosh, K., Connor, U., & Gokpinar-Shelton, E. (2017). What intercultural rhetoric can bring to EAP/ESP writing studies in an English as a lingua franca world. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 29, 12-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2017.09.001

Metz, C. (2021, July 20). Can A.I. grade your next test? The New York Times.. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/20/technology/ai-education-neural-networks.html

NeJame, L., Bharadwaj, R., Shaw, C., & Fox, K. (2023, April 25). Generative AI in higher education: From fear to experimentation, embracing AI’s potential. Tyton Partners. https://tytonpartners.com/generative-ai-in-higher-education-from-fear-to-experimentation-embracing-ais-potential/

Shwetz, K., & Assif, M. (2023, February 28). Teaching peer feedback: How we can do better. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2023/03/01/student-peer-review-feedback-requires-guidance-and-structure-opinion

Turner, E. (2023). Peer review and the benefits of anxiety in the academic writing classroom. In P. Jackson & C. Weaver (Eds.), Rethinking peer review: Critical reflections on a pedagogical practice (pp. 147-167). WAC Clearinghouse. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2023.1961.2.07

Wardle, E. (2009). “Mutt genres” and the goal of FYC: Can we help students write the genres of the university? College Composition and Communication, 60(4), 765-789.

Warschauer, M., Tseng, W., Yim, S., Webster, T., Jacob, S., Du, Q., & Tate, T. (2023). The affordances and contradictions of AI-generated text for writers of English as a second or foreign language. Journal of Second Language Writing, 62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2023.101071

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., & Hattie, J. (2020). The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03087

Appendix 1: Bean’s Hierarchy

Credit: Concordia University. Stable link: https://www.cui.edu/Portals/0/uploadedfiles/StudentLife/Writing%20Center/BeanHierarchyChart.pdf

Appendix 2: First Lesson Plan Using Chat GPT for Peer Review

Lesson 1 Objective:

Equip first-year composition students with the skills to use AI (specifically ChatGPT) to augment the peer review process of thesis-driven argument papers. By the end of the two sessions, students should be able to effectively incorporate AI feedback into their review process and offer constructive feedback to their peers.

Period 1: Introduction to AI and Preparing for Peer Review (45 minutes)

Materials Needed:

- Computers with internet access

- GPT interface or platform access

- Copies of Bean’s hierarchy for reference

- Prompts for ChatGPT (optional; see Appendix 4)

- Sample argument papers

- Peer review guidelines handout

Introduction (10 minutes)

- Discussion of Traditional Peer Review (5 minutes): Discuss the benefits and challenges of the traditional peer review process. Elicit students’ prior knowledge and experiences.

- Introduction to AI and GPT (5 minutes): Briefly explain what ChatGPT is and how it can be a complementary tool for peer review such as speed and lowering anxiety.

Instruction (20 minutes)

- Demonstration with GPT (10 minutes): Using a sample argument essay, demonstrate how to input text into GPT and how to use specific prompts tailored to Bean’s hierarchy.

- Guided Practice (10 minutes): In pairs, students practice inputting another sample essay into GPT and using Bean’s hierarchy prompts. They should jot down GPT’s feedback with the aim of sharing it with their peer.

Preparation for Peer Review (15 minutes)

- Overview of Peer Review Process (5 minutes): Explain the process they will follow during the next class. Emphasize the importance of specific, constructive, and actionable feedback.

- Peer Review Guidelines (5 minutes): Discuss guidelines, emphasizing what to look for and how to offer feedback (the particulars are up to the instructor here).

- Assignment (5 minutes): Instruct students to bring two printed copies of their argument essay drafts to the next class for the peer review session. One copy will be for their peer, and the other will be for them to reference while receiving feedback.

Appendix 3: Second Lesson Plan Using Chat GPT for Peer Review

Lesson 2 Objective:

Students will integrate both human and AI-generated feedback into the peer review process for argumentative papers. By the end of the session, students should be proficient in using ChatGPT for feedback, able to compare it with their own initial reviews, and prepared to discuss and apply a comprehensive set of revisions to their drafts. The lesson also aims to stimulate critical thinking and reflection on the role of AI in academic writing.

Period 2: GPT-Assisted Peer Review Session (45 minutes)

Materials Needed:

- Computers with internet access

- GPT interface or platform access

- Copies of Bean’s hierarchy for reference

- Prompts for ChatGPT (optional; see Appendix 2)

- Students’ draft argument papers, writing prompt, and rubric

- Peer review worksheets or digital forms (optional)

Setup (5 minutes)

- Pair up students. If there’s an odd number, create a group of three. Exchange one copy of their drafts with their peer.

Initial Review (10 minutes)

- Students read their peer’s argument paper without GPT, making preliminary notes on strengths, areas of improvement, clarity of argument, etc.

GPT-Assisted Review (20 minutes)

- Input into GPT (5 minutes): Students input sections of their peer’s essay into GPT along with the assignment prompt and rubric.

- Review with GPT Prompts (10 minutes): Using prompts and instructions based on Bean’s hierarchy, students take note of the feedback provided by GPT.

- Comparison (5 minutes): Students briefly compare their initial impressions with GPT’s feedback.

Feedback Discussion (10 minutes)

- In pairs or groups, students discuss the feedback, pointing out areas of agreement and any discrepancies between their review and GPT’s feedback.

Conclusion (Wrap-Up and Homework Assignment – 5 minutes)

- Wrap-Up: Students should have a list of constructive feedback for their argument paper drafts, drawing from both personal insights and GPT’s suggestions.

- Homework 1: Direct students to revise their drafts based on the feedback they’ve received. Encourage them to consider both human and AI feedback but to use their judgment in making revisions.

- Homework 2: Assign a reflection essay that encourages students to consider the merits, drawbacks, and their feelings about using GenAI for peer review and/or academic work in general.

Appendix 4: Useful Prompts for ChatGPT

This can be distributed as a handout or projected on the screen, but before doing so I recommend having students look at Bean’s hierarchy and brainstorm questions or tasks they might ask the GenAI to do for each of Bean’s levels following a think-pair-share protocol.

1. Assignment Fulfillment

- Does the essay meet the criteria and requirements outlined in the assignment?

- Point out any sections that seem off-topic or irrelevant to the assignment.

- Are all the required sources or references included and properly cited?

- Which parts of the assignment criteria are strongly met, and which are weakly addressed?

- Highlight the areas that best align with the assignment’s objectives.

2. Thesis Presence

- Identify the thesis statement in this essay.

- Does the main argument of the essay come through clearly?

- Is the thesis statement arguable and not just a statement of fact?

- How effectively does the thesis set the tone for the entire essay?

- Point out any sections that might detract from or dilute the thesis.

3. Strength of Argument

- Analyze the strength and validity of the essay’s main argument.

- Are there enough evidence and examples to support the claims made?

- Highlight any assertions that seem unsupported or weak.

- Do the counterarguments strengthen the essay’s overall position? Why or why not?

- Identify the strongest and weakest points in the argument.

4. Macro Organization

- Analyze the essay’s overall structure and flow.

- Does the essay have a clear introduction, body, and conclusion?

- Highlight any transitions that effectively link the major sections.

- Identify areas where the progression of ideas might seem jumbled or out of place.

- Is there a logical sequence from the problem statement to the solution or conclusion?

5. Micro Organization

- Assess the development and coherence within individual paragraphs.

- Highlight the topic sentence of each paragraph.

- Point out any paragraphs that seem to diverge from their main idea.

- Are there smooth transitions between sentences?

- Identify any paragraph that might benefit from restructuring or reordering of sentences.

6. Stylistic Issues

- Point out any sentences or phrases that seem overly complex or convoluted.

- Are there any clichés, redundancies, or repetitive words/phrases?

- Highlight any passive voice constructions that could be more effective in the active voice.

- Assess the essay for its tone. Is it consistently formal/informal?

- Are there words or phrases that might be too jargony or technical for the intended audience?

7. Grammar

- Identify any grammatical or punctuation errors in this essay.

- Highlight any subject-verb agreement mistakes.

- Point out any misuse of tenses.

- Are there any issues with pronoun reference or consistency?

- Highlight any sentences that seem fragmentary or run-on.

Appendix 5: Reflective Writing Prompt – Utilizing AI in Peer Review

In 300-500 words, reflect on your experience using ChatGPT for peer review. Consider some of the following guiding questions and ideas as you reflect and write your reflection:

- Initial Impressions: What were your expectations when you first heard about using GPT for peer review? Were they met or did something surprise you?

- Advantages: What strengths did you observe in GPT’s feedback? Were there moments when you felt that the AI caught something you might have overlooked or gave feedback that felt particularly insightful?

- Disadvantages: Were there instances where GPT’s feedback felt out of place or failed to capture the nuances of the text? Did you encounter moments where human intuition seemed more appropriate than AI analysis?

- Comfort Level: How comfortable were you with trusting an AI tool with providing feedback on writing, which is inherently a very human and personal endeavor? Did you feel the tool was impersonal, or were you relieved by its unbiased nature?

- Style and Personal Touches: Writing, especially in academia, often invites a blend of standard expectations and individual voice. Do you feel that using GPT might push writers too much towards a generic style? Or do you see it as a tool to refine one’s voice within academic guidelines?

- Standard Academic English Concerns: GPT is designed to understand and produce text based on vast data, often conforming to standard academic English. How do you feel about this? Were there moments where it challenged idiomatic or cultural expressions in your writing?

- Broader Implications: Can you think of other areas in academic life where GPT or similar AI tools might be beneficial? Conversely, are there spaces where you feel such tools should not venture?

- Personal Growth and Future Use: How has this experience shaped your view on the integration of AI in academic processes? Will you consider using GPT or similar tools in your future writing endeavors?

Tip:

Remember, there’s no right or wrong reflection. This exercise is an opportunity to explore your thoughts, feelings, and predictions about the evolving landscape of academia with the introduction of Generative AI tools like ChatGPT.