4 Developing Media and Information Literacy through Dialogues about AI

Rosa Thornley and Dory Rosenberg

Abstract

Inviting students to dialogue about Artificial Intelligence (AI) can help to develop media and information literacy. Instead of establishing restrictive policies, we present a method for instructor-facilitated dialogues to teach students to analyze, evaluate, and interact with generative language models. This recursive inquiry process causes students to critically think about the spectrum of AI capabilities and limitations. Practicing this inquiry habit over time directs students towards intuitively questioning the AI which leads them to govern their own choices when they become rhetorically aware of emerging technologies and how it will affect their own research and writing. For instructors in higher education, the dialogue provides space to better understand how students are engaging with AI which will improve teaching pedagogies in anticipation of future innovation. This chapter provides the framework for these dialogues, along with a lesson plan that can be adapted and implemented across disciplines.

Keywords: media and information literacy, generative artificial intelligence, student engagement, publication bias, inquiry-based learning

Introduction

Imagine an incoming first-year student just finished their first day of orientation, a day commonly spent reviewing course syllabi and policies. Perhaps artificial intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT are banned in some courses, limited to specific assignments for others, or not mentioned at all. Without institution-wide policy, what kind of impression might they have of generative AI tools, especially if they’ve never actively used generative language models?

Many educators are in a position to create policies about how AI is used in their classes; however, institutional or departmental guidelines for class policies are generally directed at weighing risks and benefits. In the first working paper published by a joint MLA-CCCC (Modern Language Association and Conference on College Composition and Communication) task force, they discussed risks and benefits of generative AI concluding that:

As organizations working together, we urge educators to respond out of a sense of our own strengths rather than operating out of fear. Rather than looking for quick fixes, we should support ongoing open and iterative processes to develop our responses.

Moving to an open dialogue, students can become smart consumers of Artificial Intelligence instead of feeling restricted. We find value in establishing a foundational dialogue with our students on how AI tools can be critically used in the research and writing process by reflecting on impacts of language, knowledge, and power. Specifically, through connecting media and information literacy principles (such as the implicit and explicit skills used when evaluating information) with emerging AI literacy definitions, we can begin to support a process of inquiry for our students to investigate not only the information produced by GAI tools we use, but more importantly, the infrastructure of these tools. Please note that throughout this chapter, we use GAI (generative artificial intelligence) and AI (artificial intelligence) interchangeably knowing that other tools may deliver a broader range of products for students than generative models.

Why Media and Information Literacy as an Entrypoint

Released in 2015, The Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education presents information literacy through a critical lens and defines information literacy as “the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning” (ACRL). Put simply, the framework identified specific skills students need to be able to identify how language, knowledge, and power impact the production and use of information.

Although AI is not new, a clear articulation of the competencies encompassed within AI literacy is still developing. One important takeaway in the literature is the clear connection between digital literacy as a prerequisite for AI literacy. Though simplified, one can think of digital literacy as being able to develop information literacy skills in a digital realm. This need to connect the literacies is clear when considering the definition of AI literacy as presented by Long & Magerko through their synthesis of interdisciplinary literature: AI literacy is “a set of competencies that enables individuals to critically evaluate AI technologies; communicate and collaborate effectively with AI; and use AI as a tool online, at home, and in the workplace” (Long & Magerko, 2020).

The implications of AI in educational settings is a global concern. In 2020 the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) released a collection of papers titled “Artificial Intelligence: Media and Information Literacy, Human Rights and Freedom of Expression.” Authors Shnurenko, Murovana, and Kushchu investigate access to information from a human rights perspective, presenting what they describe as a chronological development of skills as a passive-to-influential engagement with media and information (Table 1). Stagnation at the passive level may be where the greatest concern lies, as expressed earlier with students who have never actively used GAI. The UNESCO team specifically calls out the integration of AI with media and information literacy skills as a way to help individuals move from passive-to-active stages, and perhaps reach the influential level of engagement. MIL “enables people to develop and practice critical thinking about what is being learned” (Shnurenko, et al., 31).

Table 1: Development of Media and Information Literacy

|

DEVELOPMENT of MEDIA and INFORMATION LITERACY (MIL) |

|

|

Passive MIL |

accessing, using and adopting media and information |

|

Active MIL |

creating, disseminating, analysing, evaluating, interacting with and influencing media and information |

|

Influential MIL |

realizing and practicing media and information rights |

The authors’ move to include “media” with information literacy (MIL) recognizes the interrelationship between emerging technologies and literacies, and that “various (digital) media, citizens, content producers, regulators (i.e. governments) and other stakeholders now operate in a dynamic MIL ecosystem, which is continuously changing and evolving” (Shnurenko et al., p.II). New developments in AI are disrupting this ecosystem, which contributes to the confusion educators and the institutions they work for experience. Barbara Fister and Alison J. Head, two prominent voices in academic librarianship, argue that “rather than finding clever ways to use ChatGPT…instructors should help students think critically and ethically about the new information infrastructures being built around us.” They emphasize our role as educators, “we shouldn’t expend our energy on whether to use ChatGPT or ban it from the classroom when the rise of generative AI raises much more important questions for us all” (2023).

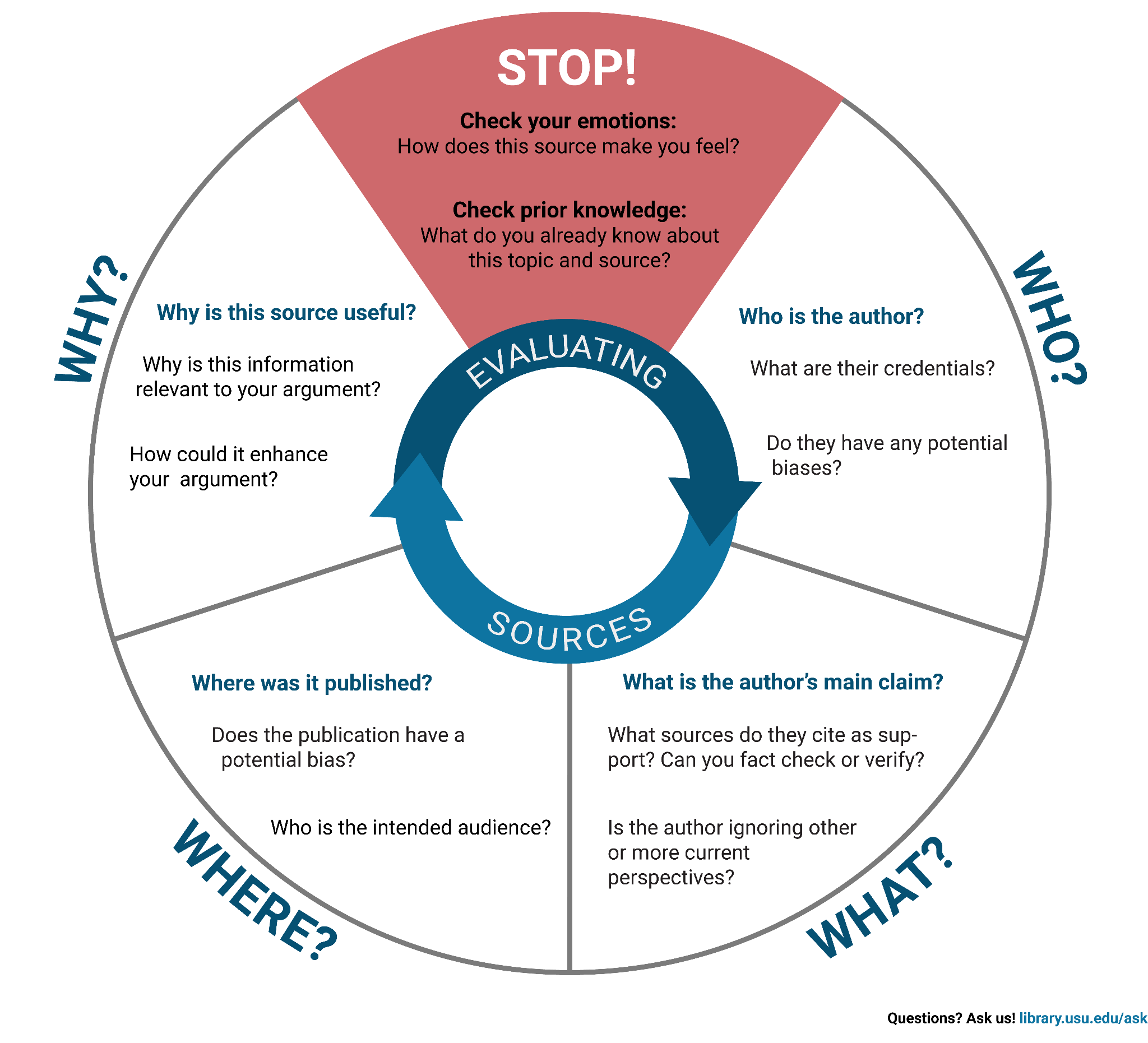

So, how can we take these frameworks and definitions of specific literacies and practically apply them in our classrooms to address these important questions raised by GAI? Collaborating as a teacher and a librarian, we have been exploring this question when supporting an intermediate composition course (ENGL 2010) at an R1 Land Grant institution. As a designated Communications Literacy course within our university’s General Education curriculum, a major outcome of ENGL 2010 is that students will be assessed on their ability to “engage with credible and relevant texts and sources appropriate to audience and purpose” (Communications Literacy 1 Rubric, n.d.). We’ve experimented with various approaches to support students in source evaluation skills over the years, and most recently have drawn upon a tool developed by Utah State University librarians called the Evaluating Sources Wheel, where students are introduced to a recursive inquiry process about sources they find in their research processes (Figure 1) (USU Libraries, n.d.). We determined that we could adapt this evaluative learning process to include generative AI tools like ChatGPT to help our students develop foundational MIL skills. While our context is specifically within a composition course, all students from freshmen to the graduate level must engage in evaluating the usefulness and credibility of information. Our goal in this chapter is to provide an example that could be tailored as needed, based on the discipline, and that describes how bridging MIL principles with AI skills can help students think more critically about the production of information, as well as develop foundational information and AI literacies.

The Evaluating Sources Wheel

Within our ENGL 2010 curriculum, the Evaluating Sources Wheel is a tool used in combination with case-based and problem-based learning (Strand et al., 2022) to engage students in thinking critically about sources found during the research process. Teaching with the evaluation wheel initiates a dialogue between students, teacher, and librarian to analyze the information they access.

The original Evaluating Sources Wheel includes five different components with specific questions to guide reflective discovery of information:

- Stop;

- Who;

- What;

- Where;

- Why?

Figure 1: Evaluating Sources Wheel

Below we provide an overview of each section of the wheel and then transition to show how we adapt it to integrate basic AI literacy skills into the evaluation process. Instead of only focusing on sources, we suggest adding resources to the evaluation—the places where we gather information:

Stop

One major goal of the evaluation wheel and how we talk about the evaluation process is to encourage students to think about sources rhetorically and to move away from an either/or mentality—a source is biased (bad) or unbiased (good). To this end, we encourage students to start their evaluation process with a pause and to consider the prior knowledge they have on a topic, as well as how a source might make them feel.

Who

When discussing a source in relation to “who,” we ask students to consider an author’s credentials and if potential biases are identifiable. We emphasize that credentials are not only titles or degrees but include a range of different types of experiences.

What

This section of the wheel asks students to identify an author’s main claim, the credibility/validity of the sources/resources they use to support that claim, and whether or not the author has balanced their ideas by fairly acknowledging other perspectives.

Where

This portion asks students to identify where a source was published, the intended audience of that publication and any clear biases affiliated with the publisher.

Why

The final portion of the wheel focuses on the usefulness of a source to a student’s argument. While not revolutionary, we wanted to emphasize the evaluation of information as a process of inquiry—and give students a moment to pause and reflect on their evaluation process as they gather research towards becoming a creator of information in their own writing.

Adapting the Evaluating Sources Wheel for AI

As discussed previously, much of the discussion in higher education about the access to AI tools has focused on risks and benefits. We propose that teaching students to evaluate the tools they use to find/create information can be a valuable approach to helping them move beyond this either/or approach, and instead develop greater awareness of how AI tools fit within a larger informational ecosystem. As such, in our sample lesson (Appendix), the AI—the resource—becomes the subject under investigation. The lesson guides students through an activity where they apply the five sections of the Evaluation Wheel to ChatGPT. Below, we describe how we adapted the evaluation wheel in consideration of AI literacy. We invite other instructors to consider how integrating a research methods activity using the Evaluation Wheel can be modified (in whole or part) for their lessons using their own disciplinary focus to investigate evolving generative AI tools and the systems of power that influence how information is created and accessed.

Stop

Start with a pause and ask students to check their emotions about AI. In the context of basic AI literacy skills, we want our students to not only think about the source itself when they’re considering its credibility or usefulness, but also the implications of the process and/or tool they used to find the source. As an instructor, this pause can also help you gauge students’ comfort with discussing AI, as well as the variability in policies they’ve encountered in their classes. This is an opportunity to discuss the confusion students experience with different AI policies or even the lack of policies.

Who

Generative AI tools present another opportunity to discuss complications in relation to the rights of authors and how we determine authorship. In considering authorship in the context of a GAI tool, students must consider the power an author exhibits through the text they have created, especially if this author is a generative language model. In investigating the “who” of an AI tool, students may be asked to investigate creators of the tool to determine positionality and bias that influence the information generated.

What

Continuing the conversation from the who question and positionality, the what can move to the search terms or input students use to get results from the AI. They are introduced to and discuss how generative AI tools may often create “hallucinations” or content that is made up, which can be a conversation opener for discussing how generative AI tools impact relationships between language and power. (“Hallucination (artificial intelligence),” 2023).

Where

The basic AI literacy awareness we want students to develop is an understanding that generative AI tools are “trained,” which introduces an inherent bias to the content the tool produces. For example, at the time of this publishing, ChatGPT was trained on North American content and thus provides a specific perspective with potential gaps in international and/or cultural topics (Heikkilä, 2023). This can also be an opportunity to help students learn basics about prompt engineering, or how a generative AI tool might respond to prompts written in different ways.

Why

This can be the richest area of the discussion as students are asked to consider why they are using AI. Risks and benefits can open the conversation, but the dialogue may show the complexity of emerging technologies and the potential implications of students using AI generative tools in their careers, both in and beyond higher education.

Impressions after a Semester of Implementation

Upon publication of this chapter, the authors together implemented this lesson for an in-person library day in four sections of English 2010 and again in English 2020: Professional Communication. Below are some initial reflections on how we modified the activity in real-time and considerations for future adaptations.

When we first discussed how we wanted to apply the Evaluating Sources Wheel to ChatGPT, we noted that many of the GAI literacy points we wanted to emphasize could fit in multiple sections of the wheel. This was even more evident through our conversations with students, and we found it helpful to highlight that sections of the wheel are interrelated and recursive.

Though not an initial part of our lesson, on the day of the activity we used the collaborative web tool Padlet to provide a space for students to participate anonymously. Each class had its own Padlet space, and we asked students to share new posts for each section of the evaluation wheel. We found that students were slow to share thoughts out loud about ChatGPT; however, when we moved our conversation online our participation rate greatly increased. Moreover, we also noted the value of anonymity that Padlet offers. Several students shared via Padlet that they were worried about using ChatGPT or confused by how it might be useful for them. On the flip side, a handful of students demonstrated greater knowledge of not only ChatGPT, but several other AI technologies. We believe that encouraging conversation with an anonymous outlet allowed space for students to be more vulnerable about what they did or did not know about AI.

We also found implementing a flipped instructional approach beneficial to this lesson and the activity. While there was still a range in the level of students’ familiarity with and knowledge of ChatGPT, the short pre-work before the lesson that asked students to read the “About” page of the generative language model helped ensure that there was some level of commonality in students’ knowledge of the tool.

For future adaptations, we see benefit in further scaffolding students’ source evaluation skills and then connecting those skills to evaluate resources such as generative AI. For example, we’d suggest first introducing the Evaluating Sources Wheel in its original form and guiding students through applying the wheel to example sources. We would then transition to crafting opportunities for students to learn about a specific generative AI tool like ChatGPT, and then collaboratively work together on how the Evaluating Sources Wheel might be adapted for evaluating generative AI tools. Then, instead of focusing on just ChatGPT in our library day activity, we could have students apply the revised Evaluation Wheel to multiple generative AI tools in order to gain a more broad understanding of various generative AI tools.

Reflecting on How AI Tools Can Help Media & Information Literacy Development

In order for students to move through the chronological development of MIL (passive, active, and influential), building this knowledge must be supported throughout a student’s academic career and curriculum. Moreover, with the new capabilities of AI, we’re in a prime time for librarians and instructors to collaborate on how we can further support students’ progress towards becoming credible creators of information. Given the limitations of what can be taught in a handful of library sessions, these classes are often focused on developing MIL skills at the passive engagement level—how to access, use, and adopt media and information. By integrating AI conversations into our approach to teaching MIL, we found that we were able to reach more complex conversations related to power and information infrastructures than we ever have before in our many years of collaborating. Active engagement with MIL asks students to create, evaluate, and interact with media and information, and we crafted the lesson with a goal of facilitating a dialogue with our students that mirrors this process of inquiry and application. While our lesson only skims the service of this active level, a structured dialogue can develop rhetorical awareness and critical thinking skills that guide students to make informed decisions about AI use at the active level.

While our lesson focuses more specifically on moving from a passive engagement with MIL to an active engagement, AI also holds implications at the influential level—realizing and practicing information rights. The authors of the UNESCO papers state that “AI is one of the major contributors to uncertainties and complexities around MIL,” and that moving from active to influential engagement with MIL will be crucial “for governance and development” (Shnurenko, et al., 32). Ultimately, our students will become the decision makers in the future. Giving them knowledge and skills to practice media and information rights helps meet the demand “to manage … more proactive approaches and strategies (Shnurenko, et al.,36).

Conclusion

Generative AI tools are not new. However, the release of ChatGPT in Fall 2022 opened the door for greater conversations and accessibility of AI tools in the classroom. Rather than confusing our students with limitations or institutional silence about how to use these tools, we believe it is imperative to explore how AI tools can foster “a new approach to media and information literacy” that can “empower [our students] in the digital era with a mindset which involves adaptation, variation and invention” (Shnurenko et al., p. 49). While our lesson plan is in a testing phase, our goal of inviting students to participate in an open dialogue connecting MIL with AI was a success. We hope this chapter and our lesson inspires teachers and librarians to make their own connections between media and information literacy and AI.

Questions to Guide Reflection and Discussion

- How can dialogue-based teaching methods enhance students’ understanding and critical thinking about artificial intelligence?

- Discuss the interplay between media literacy and AI literacy as outlined in the chapter. How do these literacies complement each other in educational settings?

- Reflect on the ethical considerations of AI use in academia as discussed in the chapter. What responsibilities do educators have?

- Explore the potential impacts of generative AI tools on students’ research and writing practices. How can educators guide students to use these tools responsibly?

- Consider the role of continuous, open dialogue in shaping students’ perceptions and use of AI. How can this approach be implemented effectively across different disciplines?

References

ACRL. (2015, February 9). Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL). https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Communications Literacy 1 Rubric. (n.d.). Utah State University. https://www.usu.edu/epc/files/general-education-designation-criteria/CL1_Learning_Outcomes_Rubric.pdf

Department of English. (n.d.). English 1010 and English 2010 Outcomes. Utah State University. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://chass.usu.edu/english/tracks/composition-resources/engl1010-engl2010-outcomes1

Fister, B. & Head, Alison J. (2023, May 4). Getting a Grip on ChatGPT. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2023/05/04/getting-grip-chatgpt

Hallucination (artificial intelligence). (2023). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hallucination_(artificial_intelligence)&oldid=1174326684

Heikkilä, M. (2023, August 13). AI literacy might be ChatGPT’s biggest lesson for schools. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/04/12/1071397/ai-literacy-might-be-chatgpts-biggest-lesson-for-schools/

Long, D., & Magerko, B. (2020). What is AI Literacy? Competencies and Design Considerations. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376727

Nadeem, R. (2023, February 15). Public Awareness of Artificial Intelligence in Everyday Activities. Pew Research Center Science & Society. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2023/02/15/public-awareness-of-artificial-intelligence-in-everyday-activities/

Shnurenko, I., Murovana, T., & Kushchu, I. (2020). Artificial intelligence: Media and information literacy, human rights and freedom of expression. UNESCO Digital Library. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000375983

Strand, K., Wishkoski, R., Sundt, A. J., & Allred, D. (2022). A Tale of Five Case Studies: Reflections on Piloting a Case-Based, Problem-Based Learning Curriculum in English Composition. In Once upon a time in the academic library: Storytelling skills for librarians (pp. 27–43). ACRL.

USU Libraries, L. (n.d.). Evaluating Sources Case Studies: Evaluation Wheel. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://libguides.usu.edu/evaluatingcasestudies/wheel

Appendix

Lesson Plan

Title: Engaging with Credible and Relevant Texts and Sources/Resources

Grade Level: University Freshmen and Sophomores

Subject: Composition Courses

Duration: 50 minutes

Learning Objectives, selected from USU’s ENGL 2010 program outcomes:

- Critical Thinking

- Writers practice critical thinking when they analyze, synthesize, interpret, and evaluate ideas, information, situations, and texts.

- Information Literacy

- Writers practice information literacy when they understand research as a process of critical inquiry and consider the influence of power on texts.

Materials:

- Writing journal

- Synchronous collaboration tool of your choice, such as: Index card, Padlet, shared Word Doc, etc… Preserving responses will aid in reflection and later use for instructors

- Student handouts of evaluation wheel

- Teacher/librarian electronic access with projector to lead discussion

- Wipe-off markers for board discussion

- Optional electronic devices for student searches

Prerequisite Knowledge:

Students should have a foundational knowledge of internet searches and generative language models such as ChatGPT, Google Bard, or Microsoft Bing. We assigned the “about” page of ChatGPT as a class reading before attending the library research day.

Teaching Method:

Interactive lesson with instructor, librarian, and student discussion

Lesson Outline:

Beginning Pause (5 min)

- Instruct students about the collaboration tool you choose to use.

- 10 words or less, what do you know about ChatGPT? (30 sec)

- Record in the synchronous collaboration tool.

- Read and respond as they appear.

- Introduction (8 min): Present the “Development [or Progression] of Media and Information Literacy” chart.

- Introduce Evaluating Sources Wheel with handout.

- Finding the Right Fit: When conducting internet research, you need to identify sources that are relevant to the topic or research question that you are searching.

- Developing a process of inquiry can help narrow the scope of your research to sources that are appropriate.

- Explain to students that in addition to sources, they can also use the evaluation process to evaluate the resources they use for finding sources.

- Finding the Right Fit: When conducting internet research, you need to identify sources that are relevant to the topic or research question that you are searching.

- Asking essential questions

- The Evaluation Wheel takes its lead from journalistic questions. Asking who, what, where, and why helps researchers establish the credibility of both their sources and resources.

Stop (5 min)

- Intro: The STOP on our Evaluating Sources Wheel starts by checking your emotions. With the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022, questions have arisen and policies have been implemented about how AI can be used in the college classroom.

- Reflection in writing journals: Take one minute and write all of the emotions you have felt about this situation over the past six months.

- Ask students to respond, by the raise of hands followed with verbal responses, about the variety of policies they are experiencing in their classes.

- Follow-up question (continue with verbal responses), “What kind of emotions does this variation in policies cultivate?”

Who (8 min)

- Intro: Reflect on rhetorical awareness. We recognize the importance of establishing the credibility of the author. In turn, as creators of information, the positionality/bias of the sources/resources we use affect our own credibility.

- Dialogue:

- As we consider the infrastructure of Artificial Intelligence, currently focusing on ChatGPT, how do we determine the authorship of sources/resources produced by the generative language model?

- Send students to their devices and have them search for the creators/owners of:

- ChatGPT

- Google Bard

- Microsoft Bing

- Open a fresh section on your collaboration tool. Ask students to title these responses “who” and record what they find. Read aloud as responses appear.

- By a raise of hands with verbal responses, ask them, “What new rhetorical questions arise from what you found?”

What (5 min)

- Intro: This section of the wheel asks you to identify an author’s main claim, the credibility/validity of the sources/resources they use to support that claim, and whether or not the author has balanced their ideas by fairly acknowledging other perspectives.

- Dialogue:

- Open a fresh section on the collaboration tool. Ask students to title new responses “what.”

- Reflect on information students read on the OpenAI Help Center reading assigned in an earlier class.

- What is a generative language model like ChatGPT? What is its functionality? What claims or disclaimers does it make about that?

- Play 2 minutes of clip from Fox 5 News Washington DC. Ask student what dangers arise from making uninformed decisions to use the product of GAI.

- Define “hallucinations” in relation to ChatGPT.

Where (5 min)

- Intro: This portion asks you to identify where a source was published, the intended audience of that publication and any clear biases affiliated with the publisher.

- Dialogue:

- Open a fresh section on the collaboration tool. Ask students to title new responses “where.”

- Where does ChatGPT gather its data from? How is it “trained”?

- Where is the potential for bias?

- How might your prompt change the results?

- Is there transparency to reverse engineer a source from ChatGPT—to find the original source—the research trail?

- How many steps does it take to go through this process versus a search on a library database?

Why (5 min)

- Intro: This is the section to ask yourself why you are using this source. Consider how it can contribute to building your knowledge of a topic as you become a creator of information as a writer.

- Dialogue:

- Note: The instructor(s)must create a safe space where students can be vulnerable about why they might use GAI instead of feeling penalized. The educators must be willing to be consistent in the claim that this is an open dialogue. Remind students that there will be multiple perspectives instead of a right or wrong answer.

- Open a fresh section on the collaboration tool. Ask students to title new responses “why.”

- Why are you using ChatGPT?

- What is it and what is it not?

- Note: The instructor(s)must create a safe space where students can be vulnerable about why they might use GAI instead of feeling penalized. The educators must be willing to be consistent in the claim that this is an open dialogue. Remind students that there will be multiple perspectives instead of a right or wrong answer.

Conclusion (2 minutes)

- The Evaluating Sources Wheel is a recursive process. Whether you apply it directly to AI-generated material or sources found elsewhere, analyzing, evaluating, interacting with and influencing media and information will develop critical thinking skills.

Reflection (5-7 minutes)

- Remind students that the evaluation wheel is a recursive process. Reflect on the STOP stage of the process.

- What new questions has this lesson prompted in your use of GAI? [If the teacher used index cards, have students record the questions on those and have them hand them in as an exit ticket]

- Have the emotions you felt in the beginning shifted? If so, what caused that shift?

- How do you plan to use this process in the future?

Teacher Reflection:

- What new questions or information arose from the dialogue?

- Determine where the dialogue, using new questions or information, can be applied in constructing future lessons addressing those things.

- How did the collaboration tool work? Is there a need for adjustments or use of a different tool?

- Evaluate responses on the collaboration tool by sorting questions into areas of the Evaluating Sources Wheel to help improve this particular lesson in the future.