5 Navigating Benefits and Concerns When Discussing GenAI Tools with Faculty and Staff

Reed Hepler

Abstract

The author works as a Digital Initiatives Librarian and is earning a second Master’s Degree in Instructional Design and Technology. He viewed ChatGPT immediately as yet another potentially useful technology. When educators at his institution promoted differing viewpoints regarding ChatGPT and other AI tools, he set out to demonstrate a method of AI integration similar to that of other technological tools. Using the Technology Consumer or Producer model and his own experience, he presented, discussed, and wrote about ChatGPT, its ethical issues, and its uses and impact on education. Reed shares his insights regarding creating instruction and training for educators. He also offers recommendations as to how educators can utilize AI in their courses.

Keywords: instructional design, technology integration, ethics, metacognition, experiential learning

“The Machine is only a tool after all, which can help humanity progress faster by taking some of the burdens of calculations and interpretations off its back. The task of the human brain remains what it has always been; that of discovering new data to be analyzed, and of devising new concepts to be tested.”

– Isaac Asimov, I, Robot

Introduction

Before we begin our foray into the murky waters of technology, ethics, qualms, and quandaries, you might want to know a little about me. I am both a librarian and an instructional designer. I have a Master’s Degree in Library and Information Science and am in a Master’s program for Instructional Design and Technology at Idaho State University. I am a Digital Initiatives Librarian and Archivist at a community college. I also aid instructional designers at this college in finding beneficial resources and helping educators integrate them into their courses.

Why is a librarian writing a chapter in a book on higher education? In the evolving landscape of education, students not only master the subject of their course but also effectively utilize technology. Digital tools require both subject and technology literacy as they increasingly impact every aspect of learning. The proliferation of generative AI (GenAI) tools underscores the need for student adeptness in navigating these new technologies. I often compare the strategies used to interact with ChatGPT with using Boolean operators and keywords in the process of database navigation.

Librarians typically teach database navigation, characterized by the use of keywords, symbols, and particular word orders, to all students at an educational institution. This essential skill set involves the strategic use of search terms to retrieve relevant information. As technologies continue to evolve and become firmly integrated into the educational sphere, these skills form a fundamental part of the student toolkit.

Therefore, it seems fitting that librarians, with their database navigation expertise, encourage using these practices and strategies for similar technologies. Noting the similarities between these tools helps students harness the full potential of tools like ChatGPT, enhancing their learning experience and equipping them with the skills they need to thrive in a digital world.

Instructional designers focus on integrating sources, technologies, and information into effective educational sessions and products. Instructional Design and Technology focuses on the effective, ethical, and timely use of technology in educational and training contexts. It strives to use technological innovations and inventions as scaffolding to support learning rather than distract from it. This chapter discusses materials developed based on library science, information literacy, and technology literacy principles and used according to instructional design best practices.

The advance of technology signaled by ChatGPT made it essential to incorporate this technology into education and communication settings. ChatGPT integration processes, or the lack thereof, set the precedent for future technology integration in the classroom. I had experience using this tool in my work as a textbook author and librarian. I knew that educators should encourage students to use GenAI to meet their educational goals, not scold them and punish them. As an instructional designer, I knew that incorporating and integrating ChatGPT into courses would require collaboration between educators, administration, and staff such as myself. I set about developing a plan to help educators with this new development.

Almost immediately after the advent of ChatGPT, four schools of thought arose in the world of educational technology.

- Fear that student use of ChatGPT primarily created new forms of unethical practices

- Confidence that students wanted to use ChatGPT in effective and constructive ways

- Fear that ChatGPT undermined systems and norms of online learning

- Confidence that ChatGPT uses resulted in innovative products and workflows to enhance instructional design, implementation, and assessment.

To help instructors navigate this new landscape, I developed a mini-campaign to educate them and help them develop the necessary skills.

Learning (and Teaching) by Experience: the TCoP Model

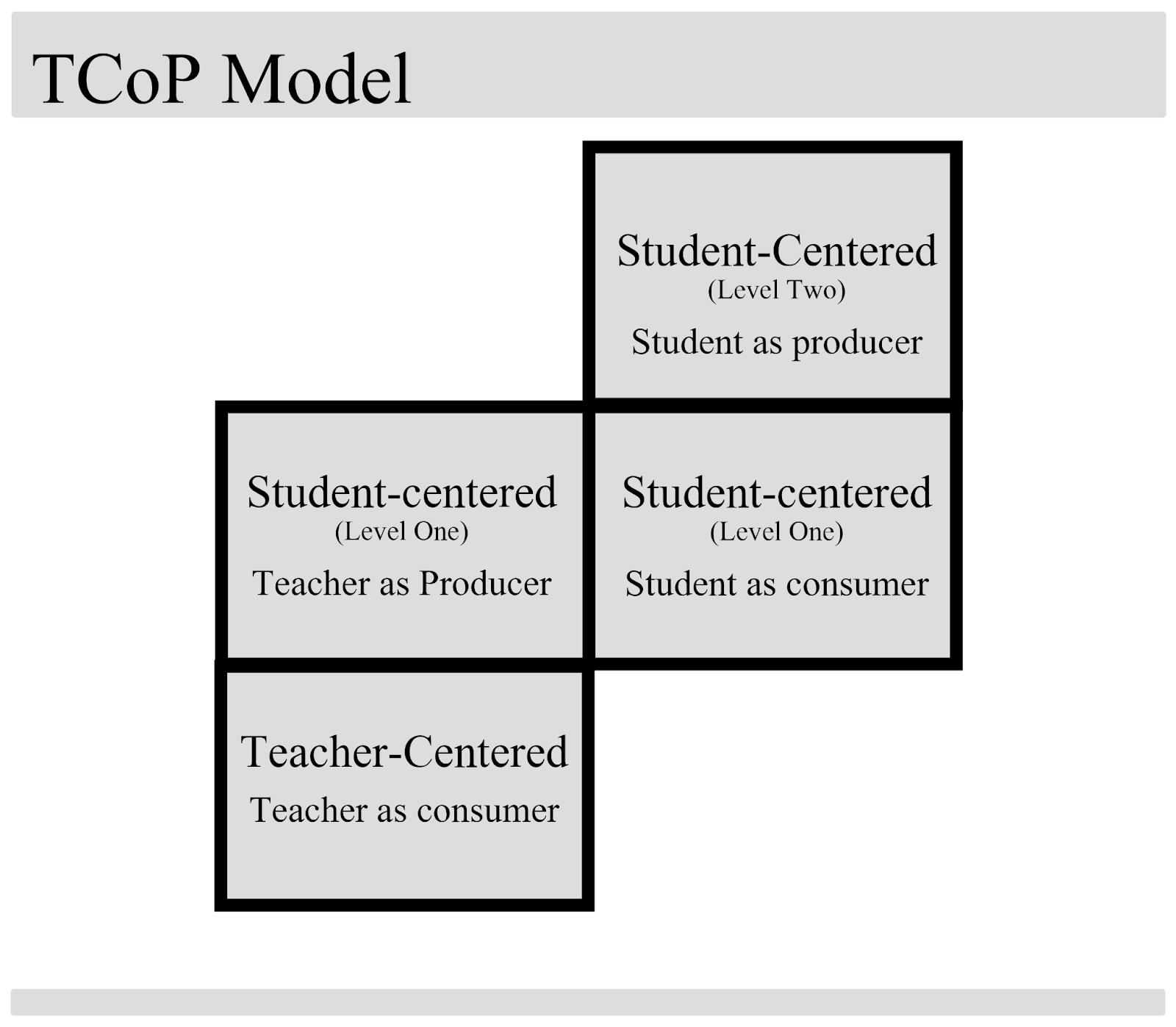

As with all other technological and educational resource advancements adopted by my institution, I developed guidelines, best practices, and workflows for others. In my position, I led efforts in using ChatGPT by example. I engaged with ChatGPT following the Technology Consumer or Producer (TCoP) Model of Technology Integration (Figure 1) created by instructional designers John Curry, Sean Jackson, and Heather Morin (Curry et al., 2022). Aligning my use of ChatGPT with this model demonstrated that ChatGPT integration into education mirrored that of other technologies. The attached image was given to me by John Curry, who approved its use in general products regarding AI integration.

Figure 1: The TCoP Model of Technology Integration

The TCoP Model of Technology Integration

The TCoP Model of Technology Integration unifies the experiences of teachers and students when interacting with technology. Application of the TCoP model includes going through the same learning process as one’s students. Educators must become comfortable with the GenAI tools they wish to encourage their students to use. At the end of their learning process, the educator’s own experiences with the technology prepare them to guide students through similar workflows and procedures. Educators perform metacognition and predict the questions or concerns of their students. By the time they present the tool to their students, they will create a thorough and effective lesson on integrating that technology into an assignment or other workflow.

In this model, every agent goes through two stages.

- First, they consume the technology and its products. They learn about its origins and how it works. They explore potential issues about the tool and gain experience with its functions. They view products of multiple types from multiple contexts and analyze those materials’ strengths and weaknesses. This research provides knowledge to the instructor for their own purposes. They do not teach or spread information until feel adequately prepared for the second step of the process. This ensures that educators have performed thorough research and exploration before they guide others (Curry et al., 984).

- Second, every person produces their own creations and presents them for others’ consumption. The target of this step lies not on the instructor but on the students. Teachers guide their students through the consumption process and prepare them to produce curated and refined outputs. They give advice and examples based on their own experience and encourage exploration and creativity. Their students come away prepared to produce materials of their own and teach others. The cycle continues with the students’ own audiences and learners (Curry et al., 985-986).

By using this model, I hoped to introduce the idea that students and educators could use GenAI tools just like other forms of technology. Not only did I use this model myself in planning my presentations and trainings, but I also gave examples of interactions and exercises for each step to enable educators to follow this same process.

Teacher as Consumer

I knew that educators needed to use ChatGPT in multiple contexts and create assignments on humanities, science, mathematics, economics, and many other topics. I had to use multiple formats for assignments or prompts. Therefore, I took the persona of multiple educators. I asked for a wide range of data outputs. I initially iterated each result three or four times. As I grew more experienced, my iterations grew to nine or ten times. I also took note of when other tools proved more useful than ChatGPT. I reviewed many textual, image, and audio outputs of ChatGPT created by others, and I enrolled in a ChatGPT Plus account myself. This enabled me to receive all of the updates to the tool, including plugins and add-ons. Directly, I consumed at least 174 distinct conversations with ChatGPT, around thirty with Dall-E, ten with Claude, and multiple conversations with alternative GenAI tools.

Teacher as Producer

To lead the way in this step of the model, I implemented ChatGPT in my textbook creation process. My open-access textbooks on Cataloging and Library Science simultaneously demonstrate the usefulness of OER materials, ChatGPT, and other technologies.

Next, I had to demonstrate the ethical and effective educational use of ChatGPT. I put myself in the place of educators in various departments at my institution and comparable institutions. I also paid attention to concerns and questions raised by faculty and staff at other institutions during inter-institutional meetings on Zoom and in communications via email.

After listening to my colleagues’ concerns and potential use cases, I created a wide range of materials, including presentations for faculty, staff, community members, and professionals in various fields. I followed best practices by iterating the generated products and making varying levels of edits. In some instances, I only performed minimal editing (for example, if I created procedural materials, such as a workflow diagram or a rubric, that did not require copyright protection). In many instances, however, such as when writing code or text for presentations, policies, or books, I needed to clarify, revise, rearrange, correct, and make other moderate and major edits to the product of ChatGPT. In addition to learning about the implementation of best practices, I trained myself to help educators, professionals, and others use GenAI tools effectively and ethically.

Student as Consumer

I presented on the use of ChatGPT according to this model at the Idaho State University Graduate Research Symposium, representing both ISU and my institution. Many people followed up with me after this presentation. I also moderated a discussion regarding AI in Education and the Workforce at the Idaho Career Technical Development Connect Conference on August 3, 2023. My last major presentation occurred at the 2023 International Convention of the Association for Education Communications and Technology. Elements of all of these presentations meshed together in the creation of this chapter.

Student as Producer

These presentations took only one form of communicating about how to use AI ethically in education and training. I also created multiple documents about high-quality prompt creation, using AI tools, and ethical concerns about AI. I disseminated these among faculty at my institution and in state and national networks. I also helped faculty members discuss and come to terms with the above-mentioned issues and concerns. Finally, I facilitated discussions of possible implementations of one or more AI tools. In all of these discussions, products, and presentations, I stressed the potential beneficial impact of GenAI on student users. I also guided participants in creating their products. Thus, their cycles in the TCoP model began.

Lessons Learned and Shared Regarding GenAI Use According to the TCoP Model

As stated above, using a GenAI tool has similarities to searching in a search engine or database. Fortunately, librarians serve as experts in database navigation using keywords, symbols, and phrases. It appears appropriate, therefore, that a librarian encourages the use of technological practices and strategies to utilize similar technologies.

ChatGPT, when used correctly, augments both the teacher and student learning experiences. As technology improves, and develops, so do educators. Future-ready educators take full advantage of the abilities of GenAI tools. As I used ChatGPT and other tools, I noted several beneficial tendencies common to all of them. I also found that certain outputs required certain tools. No GenAI tool can create the ideal form of every output.

Output Quality

The quality of my inputs directly influenced the quality of the output of ChatGPT. Whenever I encourage educators to incorporate technology into their curricula, programs, or assignments, I tell them this mantra: “Technological success is not about technology. It’s about the user.” If you want high-quality output, you need to take the time to create high-quality input.

After the tool generates its first output, I recommend that users alter their first prompts or at least ask ChatGPT to change its output. Do this at least three times. Tell ChatGPT to data and ask for more precision. Hyperparameters significantly alter iterating outputs. These parameter options include temperature and top-p values and penalties related to frequency, redundancy, and presence.

Furthermore, in many cases (especially academic and professional), best practices in writing fields advise that users not simply copy and paste ChatGPT’s work and pass it off as their own. They should At least proofread and verify the data given by ChatGPT. Verify all links and make sure that referenced sources truly exist. Furthermore, thoroughly ascertain that their content validates the claims made by ChatGPT.

During the first step of this process, using ChatGPT to write my textbook chapters, I saved a large amount of time writing about general concepts. However, I felt that the high-level descriptions of topics in ChatGPT’s initial products failed to delve deep enough. I took the sentences and paragraphs generated by ChatGPT and filled them out with details and references that only I knew. Still, I estimate that I published the textbooks around two weeks earlier than I initially expected.

Typical ChatGPT responses to undetailed and non-specific prompts merited a B average grade, according to CNN (Kelly, 2023).You may improve this by creating more detailed prompts. Additionally, the mediocre quality of most ChatGPT content encourages users to take the product generated and add manual improvements. ChatGPT product lacks a sense of humanity and creativity. As mentioned earlier, Hyperparameters improve the creativity and spontaneity of generated text. However, adding the presence of your unique voice is one of the most important additions and changes.

Multiplicity and Constant Improvement of AI Tools

While I reference ChatGPT alone, almost all digital purposes, and some other ones, offer opportunities to use different AI. Even tools that with a similar output can function in very different ways. Be circumspect when choosing tools. Judge each tool by its performance in its intended function rather than any secondary uses.

For example, Google Bard and Bing AI serve mainly as discovery tools that connect to preexisting search engines as a way to search conversationally. They incorporate elements of large language models into their functions and outputs, but their main function differs from that of ChatGPT. The original purpose of ChatGPT was to create language and communication forms. Connection to the Internet only occurred as late as September 2023.

Recognizing the initial purpose of a tool enables us to temper our expectations. In several of my communications or conversations with faculty members and others, they complained that “ChatGPT lies,” or “ChatGPT does not know what it is talking about.” In a way, the design of ChatGPT deliberately encouraged this behavior. If it does not know an answer, OpenAI has instructed it to at least attempt an answer anyway. ChatGPT does not transfer information. It provides, analyzes, and organizes content based on the semantics and syntax of the English language and its usage rules and norms.

Take conscientious care not to misuse or misappropriate any technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI). While I use ChatGPT for text generation, I also am familiar with Dall-E, Adobe Firefly, and other image-based generation tools. I also use audio and audiovisual GenAI tools. As time goes on, GenAI tools arise for virtually every output imaginable. Efficient users find the right tool in the right way for the right type of output. Any student who persists and experiments eventually learns the optimal workflows for using multiple tools.

Note that while the guidelines of this chapter pertain to all GenAI tools, they may not accurately reflect the specifics of individual tools’ features at the time of publication. Current incompatibility of a particular tool with a certain type of input does not guarantee long-term uselessness with the input. Creators regularly change and adapt their tools. For example, a single-purpose tool may become multimodal. The journey of ChatGPT to its present iteration (as of October 2023) demonstrates this excellently. ChatGPT initially focused on text- and keyword-based data, not mathematics or scientific theories. As of October 2023, users of the open and free tool can still access these abilities. GPT4 features plugins and other services add to these attributes.

The inability of ChatGPT to generate images was one of the main shortcomings I noted regarding ChatGPT compared to tools from other institutions. This all changed less than a year after the tool’s original release. In March 2023, OpenAI released GPT 4. Its abilities dwarf those of GPT 3.5. With each plugin and external service connected to GPT 4, its abilities and reliability expanded and improved. As of October 15, 2023, when the Dalle-3 came out, ChatGPT Plus users created high-quality images that avoided many of the biases and weaknesses of Dalle-2 and Bing.

One of my professional acquaintances, Nathan Hunter, wrote an extremely helpful book on using ChatGPT and MidJourney to create images a few months after MidJourney came out. In October 2023, however, he wrote in an update in another book about ChatGPT that he reexamined his commitment to using MidJourney because of the extremely high quality of Dalle-3 outputs. He also noted that whereas other tools only responded to English, Dalle-3 creates outputs for prompts in multiple languages.

In September 2023, when GPT 4 integrated with Microsoft Bing in Bing Creative Mode, the data in the tool expanded from 2021 to 2023. Now, GPT 4 generates text regarding the present day, especially if users opt to try the Bing-integrated version. Additionally, the current version of ChatGPT acknowledges where gaps may occur in its knowledge or competencies. It recommends alternative sources of information. Other uses of the expanded version of ChatGPT include advanced image and data analysis, data visualization, travel and tourist recommendations, and many other products.

Openness and Accessibility of ChatGPT

ChatGPT has the unique quality of being a truly open major technological advance. Users accessed all abilities of ChatGPT before OpenAI placed it behind a quasi-paywall in February. However, the case for it being labeled open today still exists. Users can take advantage of the basic ChatGPT 3.5 version for free at almost any time. OpenAI administers compensated access to GPT 4, but the highly capable GPT 3.5 remains free and open to the public. Therefore, OpenAI still offers an open product.

The time needed to become familiar with GenAI products or services further impacts the user. While these technologies promise extraordinary possibilities, users sacrifice time, money, or a combination of both to take advantage. The simplicity of ChatGPT’s interface gives users a short, low learning curve with plenty of examples and guides along the way. While you have to take time to learn how to engineer prompts, learning the basics of operating the service only requires a little over one minute.

Acknowledging and Navigating Ethical Issues Related to Student GenAI Use

Instructional designers commonly state the aphorism that educators should not use technology simply for the sake of using technology. The most effective educators ensure that technologies used for educational purposes directly impact positive trends in student understanding, retention, and application of the course material.

When GenAI became widespread, no evidence-based studies or prominent use cases of these tools existed. Widespread fears also abounded about potential student misuse of the tools. Furthermore, professionals in many fields raised concerns about ethics, productivity, plagiarism, and other implications of the tools.

These issues seemed insurmountable. Instructors practiced multiple methods of trying to acknowledge and handle them. Some instructors at my institution prohibited student use of GenAI tools, claiming that GenAI use inherently contradicted academic integrity. Others held active conversations with their students and collaboratively created class or course AI policies to govern AI-influenced submissions. Still others let their students do anything they wanted and practiced a kind of salutary neglect when assignments were turned in with clear signs of copying and pasting GenAI outputs.

Through the sincere and motivated use of the TCoP Model, whether they knew it or not, these educators saw how to navigate these roadblocks. As you read these concerns and debates, consider how experiential learning, whether through the TCoP Model or another method, gives you insight into navigating these issues. Prepare to answer your students’ questions and concerns as they navigate the many types of AI tools and products.

Plagiarism

Some educators center their arguments against GenAI on plagiarism. The capacity of these tools to generate text that mirrors human writing raises the possibility of creating unoriginal, derivative work. This concern permeates the academic sphere, where the use of GenAI for the effortless completion of assignments undermines the process of authentic learning (Gordijn and Have, 2023). In recent months, AI adopters view programs as productivity tools rather than authors. They view the individual who created and used the prompts and iterated the outputs as the author. Some professionals have even called this era the “post-plagiarism” age. Best practice tells us to iterate outputs and manipulate the end product manually before using it and claiming authorship. Plagiarism worries hold no sway as long as the idea for the product and the main aspects of the result originate from the user. The Terms of Use by OpenAI for all of its products complement this idea (March 14, 2023).

When using the TCoP Model, educators demonstrate best practices regarding GenAI to their students. If students consume materials created by prompt engineers and GenAI tools using best practices, their products typically follow suit. Educators who wish to train students to avoid plagiarism proactively and thoroughly model a productive and ethical workflow.

Bias

Bias in the responses generated by AI also motivates educator trepidation. These models, trained on extensive datasets, may unintentionally learn and replicate the biases present in those datasets. Skewed and prejudiced outputs occasionally result. Educators raised significant concerns about this tendency in a field that prizes fairness and impartiality (Gordijn and Have, 2023; Elgersma, 2023).

The TCoP Model enables educators to address this concern just like they address fears regarding plagiarism. Librarians teach controlling for biases to all researchers who come to them for help. Researchers should search for a broad range of resources by many authors and publishers on a topic. Also, note the backgrounds of authors, methodologies, and other aspects of a given text. When teaching about these tools, proactively show students how to note possible biases that crept into the models of GenAI tools. Ask them to critique your own products for biases and other issues. Additionally, remind students about the purpose of keywords in database research. Certain words, phrases, and orders =affect the nature of the results. In a similar fashion, these same elements affect GenAI output.

Selectiveness of Response

From a usability perspective, GenAI tools like ChatGPT sometimes produce arbitrary or selective responses or fail to respond appropriately to certain prompts. They also generate repetitive phrases, which limit their effectiveness in an educational or training context. However, these tools also occasionally produce incorrect responses, necessitating human correction. A valuable learning opportunity such as this allows users to critically engage with the information provided by the AI (Deng and Lin, 2023). Again, librarians continuously demonstrate much experience with this skill. Critical reading of sources and evaluation of content accuracy and authoritativeness serve as the foundations of high-quality research.

Accusations of Cheating

One of the most visible controversies regarding GenAI involves the swift opposition educators had regarding student use of ChatGPT. As a matter of fact, an article warning about the negative impact of ChatGPT on education introduced many readers to the tool. Although not an educator, commentator Stephen Marche echoes many teachers’ concerns in his now-widely-read article “The College Essay is Dead,” in The Atlantic (Marche, 2022). The metadata of the site holds two other titles for this article: “Will ChatGPT kill the College Essay?,” and “ChatGPT AI Writing College Student Essays.” These titles shed some light on the intentions and perspective of Marche in writing this article. He thoroughly discusses his subject and argument, and his sources are credible. He ended up with the main argument that ChatGPT forces humanities- and sciences-centered professionals to work together to adapt to its capabilities and implications. However, his outlook on the required time is somewhat pessimistic. Marche estimates a minimum of ten years before education and industry develop procedures and standards to cope with AI-generated products.

In the first section of Marche’s essay, he notes that students may potentially use the technology to “cheat” in their assignments. He also noted that some students did not consider ChatGPT use as cheating because it was a tool they used, to compose their thoughts and research into a narrative. The service did not create an essay out of thin air but rather integrated the data that the students included in their prompts. This section sparked the opposition of educators to ChatGPT. Many educators, at least initially, only saw it as a potential tool for students looking to cheat. This meant that traditional homework and educational assignments became useless. Any student, teachers argued, can write prompts for ChatGPT (Herman, 2022).

Accusations of Plagiarism

Shortly after Marche wrote his essay, several prominent schools including the entire school districts of Seattle, Baltimore, Los Angeles, and New York, banned the use of ChatGPT by students using school network computers (Johnson, 2023). Each of the districts based their decisions on the fear that students viewed GenAI as a new tool to “cheat” and bypass the expectations for “original thought”. In other words, they feared ChatGPT being used as a plagiarism tool. These stated reasons initiated a continuous debate over the past year on the nature of GenAI tools and their outputs.

In terms of the content generated by its Services, OpenAI’s Terms of Use states that users own the copyright of the Input given to the tools. Additionally, while OpenAI technically owns the copyright of the Output, the Terms of Service explicitly state that “OpenAI… assigns to [users] all its right, title and interest in and to Output” as long as you comply with the Terms of Service and applicable laws (OpenAI, March 14, 2023). Users claim the responsibility for determining whether their input and/or output violate these requirements, whether they are cognizant of this obligation or not. Therefore, legally, you cannot plagiarize ChatGPT output. You essentially own the copyright of that output. On the other hand, you must state somewhere that you used ChatGPT, or at least AI, to create your product. You should not represent the product of this tool as being exclusively created by a human.

Conclusion

Just like all other fields, education has proponents and detractors of GenAI tools and their products. The conversations going on in the world of education, in my view, have immense importance because our conversations establish the possibilities of those other fields’ conversations. If students from our institutions go into the workforce without any knowledge of how to integrate new technologies into their workflows, they will be unprepared to handle questions of effective and ethical use or best practices. Educators must train the future leaders of all industries to adapt and utilize new technologies as soon as companies develop them.

Future hazards exist with another alternative. If proactive students decide to use GenAI, adapting and utilizing it on their own because of a lack of educator interest, They may go their entire educational careers without any input from their educators on ethical issues or best practices. They might rely on information from questionable sources. They run the risk of misusing GenAI tools. They may not learn to think critically about AI tools, their outputs, or their impact on consumers in the workforce. Educators carry a responsibility to educate their students about both possibilities and issues with all technology, including GenAI.

In the TCoP Model of Technology Integration, educators use metacognition to analyze their learning experiences with GenAI. Then, they create products for student consumption. They use these and other materials to guide their students through similar experiences. These learners then spread their knowledge to others.

Alongside the benefits of GenAI tools, including the affordability and open access nature of many of them, professionals and educators have all expressed concerns in the workplace about widespread use. Educators, students, and professionals must have conversations about workflows, best practices, and concerns about plagiarism and copyright. As educators understand these issues and learn through experience, they prepare themselves to help students navigate this complicated landscape.

Questions to Guide Reflection and Discussion

- Explore the different schools of thought among educators regarding the use of GenAI tools like ChatGPT in education. What are the potential benefits and drawbacks from each perspective?

- Discuss the ethical considerations that should guide the integration of GenAI tools into educational practices.

- How can institutions balance the enthusiasm for new technological tools with the need to address concerns about academic integrity and ethical usage?

- Reflect on the role of faculty and staff in shaping policies for AI tool usage. How can their insights and concerns be effectively incorporated into decision-making processes?

- Consider the impact of GenAI tools on educational equity. How can these tools be used to support all students, including those from disadvantaged backgrounds?

References

Curry, J. H., Jackson, S. R., & Morin, H. (2022). It’s not just the how, but also the WHO: The TCoP model of technology integration. TechTrends, 66(6), 980–987. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-022-00797-8.

Deng, J., Lin, Y. (2023). The benefits and challenges of ChatGPT: An overview. Frontiers in Computing and Intelligent Systems, 2(2), 81–83. https://doi.org/10.54097/fcis.v2i2.4465.

Dobrin, Sidney I. (2023). Talking about generative AI: A guide for educators. Broadview Press. https://broadviewpress.com/product/talking-generative-ai/#tab-description.

Elgersma, C. (2023, February 14). ChatGPT and beyond: How to handle AI in schools. Common Sense Education. Retrieved March 9, 2023, https://www.commonsense.org/education/articles/chatgpt-and-beyond-how-to-handle-ai-in-schools.

Gordijn, B., Have, H. ten. (2023). ChatGPT: Evolution or revolution? Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 26(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-023-10136-0.

Herman, D. (2022, December 9). The end of high school English. The Atlantic. Retrieved March 29, 2023, from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/12/openai-chatgpt-writing-high-school-english-essay/672412/.

Hunter, N. (2023). The art of prompt engineering with ChatGPT: Accessible edition. (1st ed., Vol. 2, Ser. Learn AI Tools the Fun Way!). ChatGPT Trainings. https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0BZ4T68Q4?ref_=dbs_m_mng_rwt_calw_tkin_1&storeType=ebooks.

John, I. (2023). The art of asking ChatGPT for high-quality answers: A complete guide to prompt engineering techniques. Nzunda Technologies Limited. https://www.amazon.com/Art-Asking-ChatGPT-High-Quality-Answers-ebook/dp/B0BT26B2SP/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=.

Johnson, A. (2023, January 31). Chatgpt in schools: Here’s where it’s banned—and how it could potentially help students. Forbes. Retrieved March 29, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/ariannajohnson/2023/01/18/chatgpt-in-schools-heres-where-its-banned-and-how-it-could-potentially-help-students/?sh=1cc8f23b6e2c.

Kelly, S. M. (2023, January 26). CHATGPT passes exams from law and Business Schools | CNN business. CNN. Retrieved March 29, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/01/26/tech/chatgpt-passes-exams/index.html.

Layton, D. (2023, January 30). CHATGPT - show me the data sources. Medium. https://medium.com/@dlaytonj2/chatgpt-show-me-the-data-sources-11e9433d57e8.

Marche, S. (2022, December 16). The college essay is dead. The Atlantic. Retrieved March 29, 2023, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/12/chatgpt-ai-writing-college-student-essays/672371/.

Open AI. (2023, March 14). Terms of use. Open AI. Retrieved March 29, 2023, https://openai.com/policies/terms-of-use.

OpenAI. (2023, March 27). GPT-4 technical report. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08774.