27 Pushing Past the First Draft: Exercises in Revision

Jacob Taylor

Abstract

This essay provides a series of global and local revision exercises for writing students to use while developing their revision processes. These revision exercises offer physical and digital possibilities, including opportunities to use AI learning models. Each of the included exercises can be done with or without the use of AI to accommodate individual preferences. The provided global revision strategies promote major structural and/or thematic revisions while requiring writing students to take risks. The local revision exercises help writing students tighten up sentences and improve minor stylistic elements while remaining focused on patterns they can begin to identify in future work. These revision exercises focus on revision as an individual activity rather than a social practice; providing guidance on seeking feedback from instructors, peers, or tutors is not within this essay’s scope, but writers should practice these exercises in addition to seeking and incorporating such feedback.

Keywords: revision process, writing process, generative AI, educational technology

Introduction

The Writer’s Guild of America authorized a strike in May of 2023 that persisted for months due to corporations’ refusal to negotiate. One of the many issues leading up to the strike was recent generative AI developments. In an interview with NPR, the actress, writer, and producer Lanett Tachell said, “We’re not here to rewrite a machine. We’re not against the use [of AI technology], you know, if we can find a way to be reasonable. But [AI] cannot be the genesis of any creation. We create these worlds” (del Barco, 2023). On May 1, 2023, the Writer’s Guild of America specifically demanded writing in its contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) regulating the use of AI technology, which AMPTP rejected and countered with an offer to hold annual information meetings about technology advancements (WGA Negotiations, 2023, pp. 2). The contract which eventually ended the strike, which went into effect in September of 2023, contained regulations on AI use very similar to the ones initially proposed by the WGA. For example, the contract states that AI cannot write or rewrite literary material, and it cannot be considered source material; however, the contract also leaves open the opportunity for writers to use AI technology with their company’s consent and while following company policies (Summary of the 2023 WGA MBA, 2023). Because of this new regulation in the use of AI technology in professional fields, writing students will benefit from learning what AI technology is and is not capable of, and from learning how to use AI technology in ethical and productive ways throughout the writing and revision processes. This essay contains a series of global and local revision exercises intended to aid students in developing their revision processes while utilizing various physical and digital tools, including AI technology. This essay discusses revision as an individual activity; however, writers should seek feedback from instructors, peers, and tutors in addition to practicing the following revision exercises.

A Note on Writing AI Prompts

As writers interact with generative AI, they will find that the AI learning model does not always respond to the prompts in the way they would like. Personally, I found some of the responses rather frustrating. This simply demonstrates some of the many limitations of this technology. In order to use it effectively, writers must learn how to manipulate it with prompts.

Andy Beatman and Samantha Sahimi (2023), from Microsoft Azure AI (one of the many new generative AI tools), provide the following advice on writing prompts:

- “Be specific and leave as little room for interpretation as possible.”

- “Including cues in your prompt can help guide the model to output aligned with your intentions.” A cue when asking AI to summarize a statement might look like “The key takeaway of the message is…” or “Key points:” followed by a bullet point.

- “Practice and gain experience in crafting prompts for different tasks.”

Sometimes simply regenerating the response can resolve the issue, but other times writers must completely rewrite the prompt to receive the desired outcome.

Global Revision

Writing a first draft is a vital part of the writing process; however, writers must be willing to engage in global revision in order to improve their writing skills and produce more effective drafts. The novelist and essayist Anne Lamott writes, “Very few writers know what they are doing until they’ve done it. […] [T]he only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really shitty first drafts” (2019, pp. 21). A “shitty” first draft can become extremely effective when writers revise globally.

Global revision changes the overall structure of an essay. When revising global issues, writers consider how different sections, paragraphs, and sentences interact with each other to convey the larger ideas and concepts the essay needs to contain. A lot of this work may feel very similar to the writing process because it requires cutting sections, rearranging sections, re-writing sections, writing new sections, and expanding sections. The main difference, however, between global revision and the initial writing process is that writers already know where the essay is going during the revision process; the essay has had time to process. Doug Downs, a professor of writing at Montana State University, writes, “A writer at the end of their first draft now sees things they did not when they began, letting them ‘drive on’ through another draft by writing what they would have said had they known at the beginning of the first draft what they now know at the end of it” (Adler-Kassner and Wardle, 2016, pp. 66). The Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist John McPhee describes how writers can utilize time spent in between drafts to generate ideas: “[Y]ou may be actually writing only two or three hours a day, but your mind, in one way or another, is working on it twenty-four hours a day—yes, while you sleep—but only if some sort of draft or earlier version already exists” (2017, pp. 160). At the end of each draft, writers gain more direction, more insight into what their essays might become, and allowing the brain time to process each draft magnifies this effect. Writers who revise globally break apart their essays and stitch them back together to access each piece’s full potential.

Global Revision Exercises

Take a New Perspective

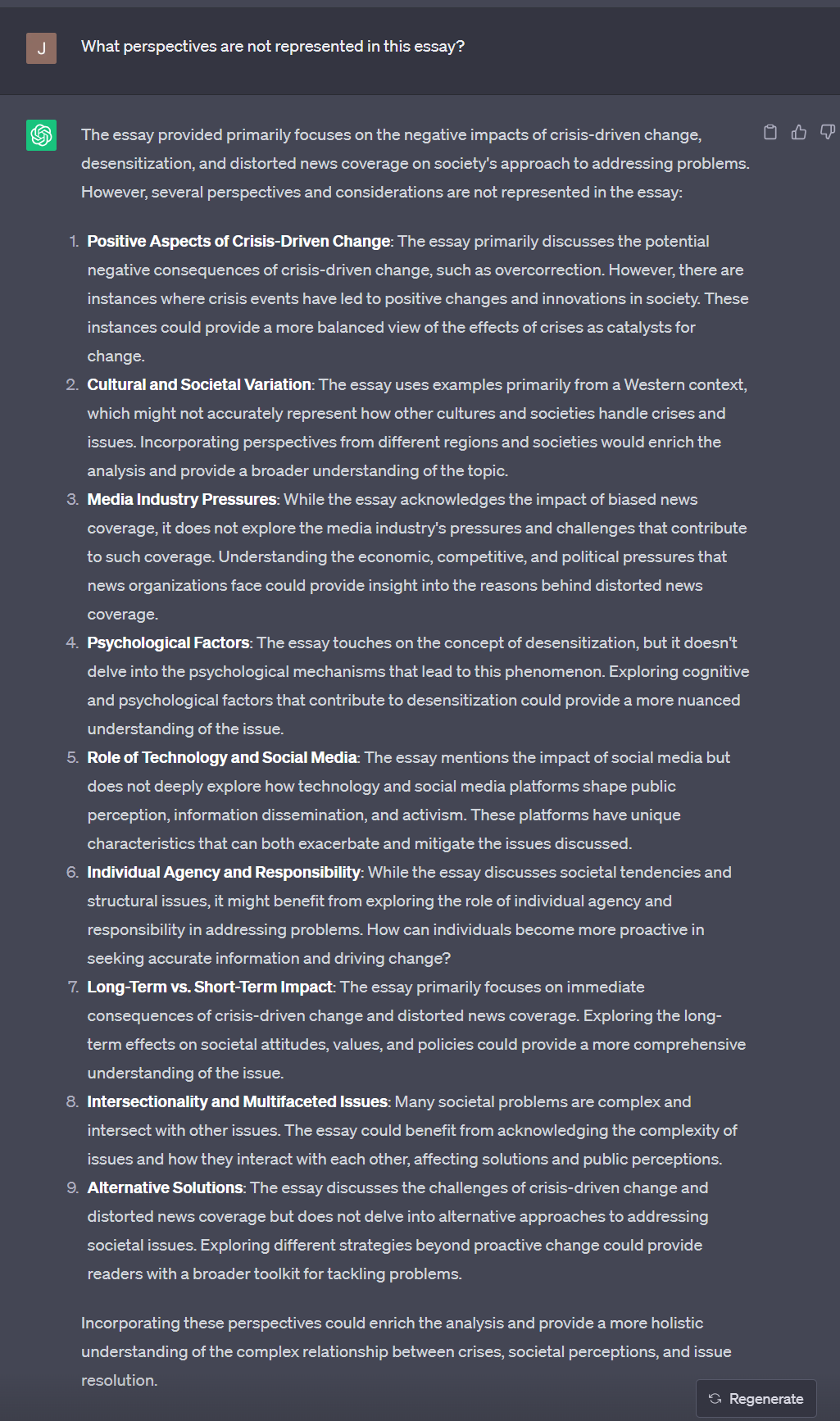

In a binary, or two-dimensional, argumentative essay, this approach to revision might be considered adding a counter argument. However, two-dimensional arguments tend to neglect the bigger picture, leaving many perspectives unheard. As shown in Figure 1, AI can help identify perspectives and points of view left unrepresented in a piece of writing. This can be helpful when writers have trouble seeing multiple perspectives within an issue or have trouble identifying bias within their own writing. In Figure 1, ChatGPT identified that the essay I fed to the chat used examples primarily from a western perspective, which imposes bias on the essay. ChatGPT writes that these examples might not “accurately represent how other cultures and societies deal with crises and issues” and suggests diversifying the examples used in the essay. This is one way that ChatGPT can identify bias or neglected perspectives writers may not be aware of.

If writers currently have evidence representing only the perspective for which they are arguing, writers should find multiple credible sources supporting an alternative (this does not mean directly opposing) point of view. If writers currently have two points of view represented in their essay, writers should find credible sources that represent a third perspective to incorporate into their essay.

Writers should try to incorporate at least two different sources that accurately represent each perspective when revising a research essay. Writers should also avoid easily refutable sources as these sources rarely represent the perspective accurately. Following these two guidelines will increase credibility and help readers be more receptive.

Writers might find alternative perspectives by considering the following:

- Specific groups of people involved with or affected by the situation

- Specific solutions, approaches, or theories proposed (or attempted) in relation to the situation

- Specific concerns or worries that arise from the situation

- Specific effects stemming from the situation

Figure 1: Example of using ChatGPT to brainstorm neglected perspectives using the prompt, “What perspectives are not represented in this essay?” (ChatGPT, personal communication, August 21, 2023.)[1]

Evidence Selection

The evidence a writer selects to back their arguments is vital to the credibility their readers grant them. It comes, largely, from the sources selected, the lines quoted, and the information paraphrased. A well-placed quote carries power, and readers may mistrust writers who chronically paraphrase; however, paraphrasing gives writers much more autonomy.

For this exercise, writers may find it helpful to copy and paste quotations into a separate “dump document” if they are reading any digital articles. Writers may choose to increase or reduce the amount of evidence in their essays during this process to make the evidence-to-analysis ratio feel more balanced.

Writers should consider using the following rules as they complete this exercise:

- Writers should not re-read the evidence they have already placed in their essay before doing this exercise to allow them to re-evaluate their sources with a fresh mind.

- Writers should avoid quotations where the source’s author summarizes content because writers can summarize any pieces of evidence that need an introduction. Instead, writers should quote the specific and unique information the source offers.

- If the relevant section of a source is citing another source, then writers should find the original source; do not play a game of telephone with sources.

Now, writers should reread each of their sources and select evidence to use in their essay from each source.

After writers have a new set of evidence, writers should compare it to the evidence originally placed in the essay. If writers selected any pieces of evidence twice, that is a good sign that writers should keep the re-selected evidence in the essay. Any evidence included in the original essay that writers did not select during this exercise is likely weak evidence that should be removed from the essay and replaced with new evidence found during the exercise. Writers may find during this exercise that their current set of sources is insufficient and will need to return to the research process to find stronger or more comprehensive sources. Writers should play around with their options, especially to see if quoting or paraphrasing feels best with each piece of evidence.

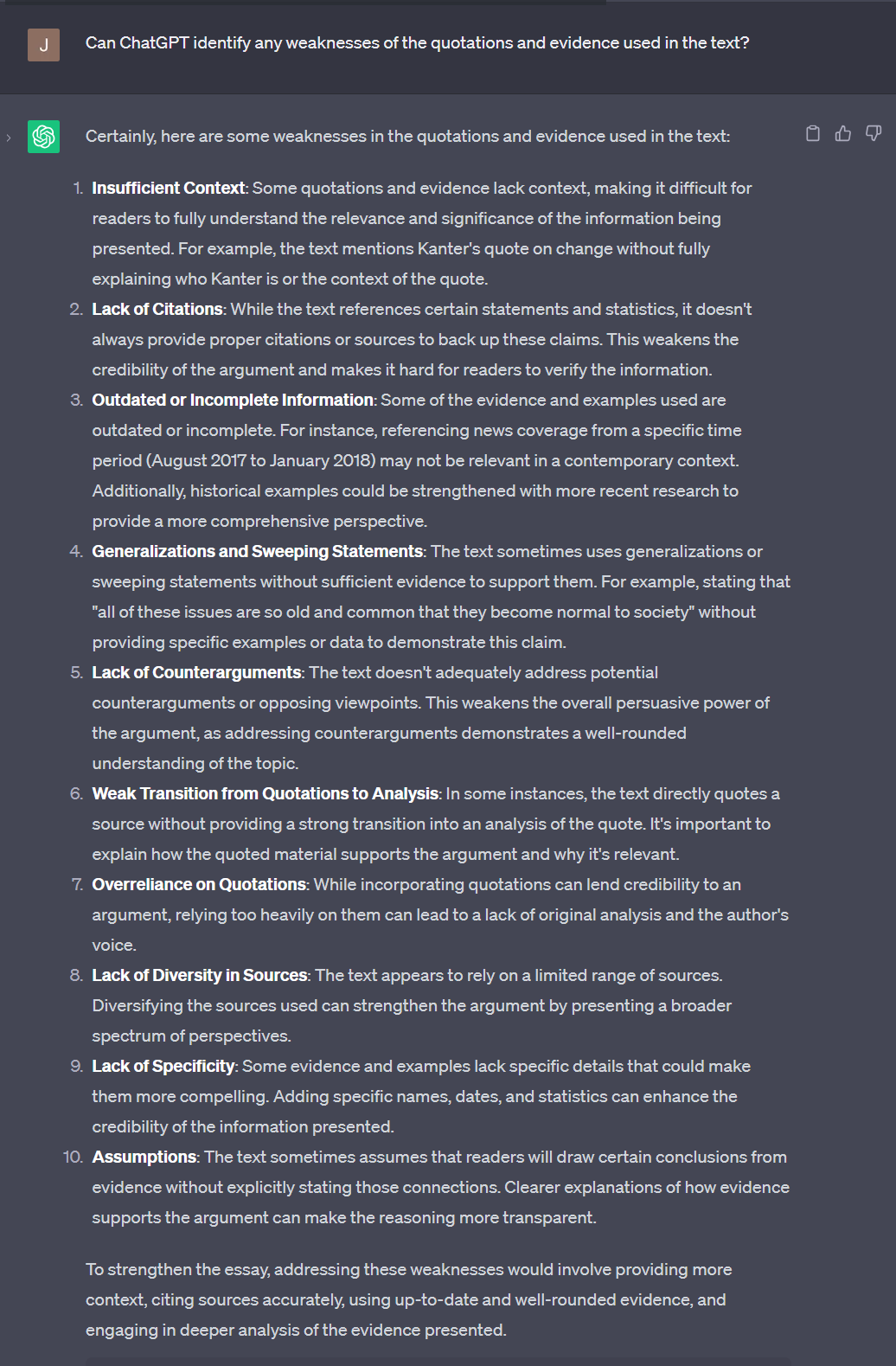

Writers can also use AI to identify weak quotations or gaps in their research, as seen in Figure 2. ChatGPT writes that the essay relies on generalizations and sweeping statements like “all of these issues are so old and common that they become normal to society” without providing examples or evidence to support those statements. When given this feedback from AI, writers may consider finding sources (or choosing quotations from the sources they have already collected) containing specific examples of the concept they wish to demonstrate in the essay. ChatGPT also writes in Figure 2 that some quotations lack sufficient context, suggesting that the writer provide more information to help readers understand the information being presented. This is something writers should be particularly aware of, especially when re-incorporating evidence back into the essay after completing the exercise.

Figure 2: Example of using ChatGPT to assess evidence quality using the prompt, “Can ChatGPT identify any weaknesses of the quotations and evidence used in the text?” (ChatGPT, personal communication, August 21, 2023.)

Jigsaw

The point of this exercise is to allow writers to freely re-organize their essays. The best way for writers to organize their ideas may not be the way they originally wrote them. For example, an essay’s conclusion might become the introduction; the second main idea in the body of an essay might become the first, or the fourth.

Writers will cut their essays up into sections. Writers should not limit themselves to breaking up sections with paragraph breaks. Writers will likely break some of their sections in the middle of a paragraph. Some sections might contain a paragraph break. Make a new section at every place where the content shifts. Writers will have to re-work the transitions and wording after they stitch their essays back together.

The Digital Exercise (Without AI)

Writers may use the headings feature in Word to complete the exercise with the following steps:

- Indent and create a “heading” at the beginning of each section using the headings feature.

- In the Navigation Tab, drag each heading up or down to rearrange the sections.

- Once happy with the new arrangement, remove all “headings” and create new transitions between the sections to ensure the essay flows smoothly and each section has necessary context.

(Writers can, of course, simply cut and paste rather than using the headings feature.)

The Digital Exercise (With AI)

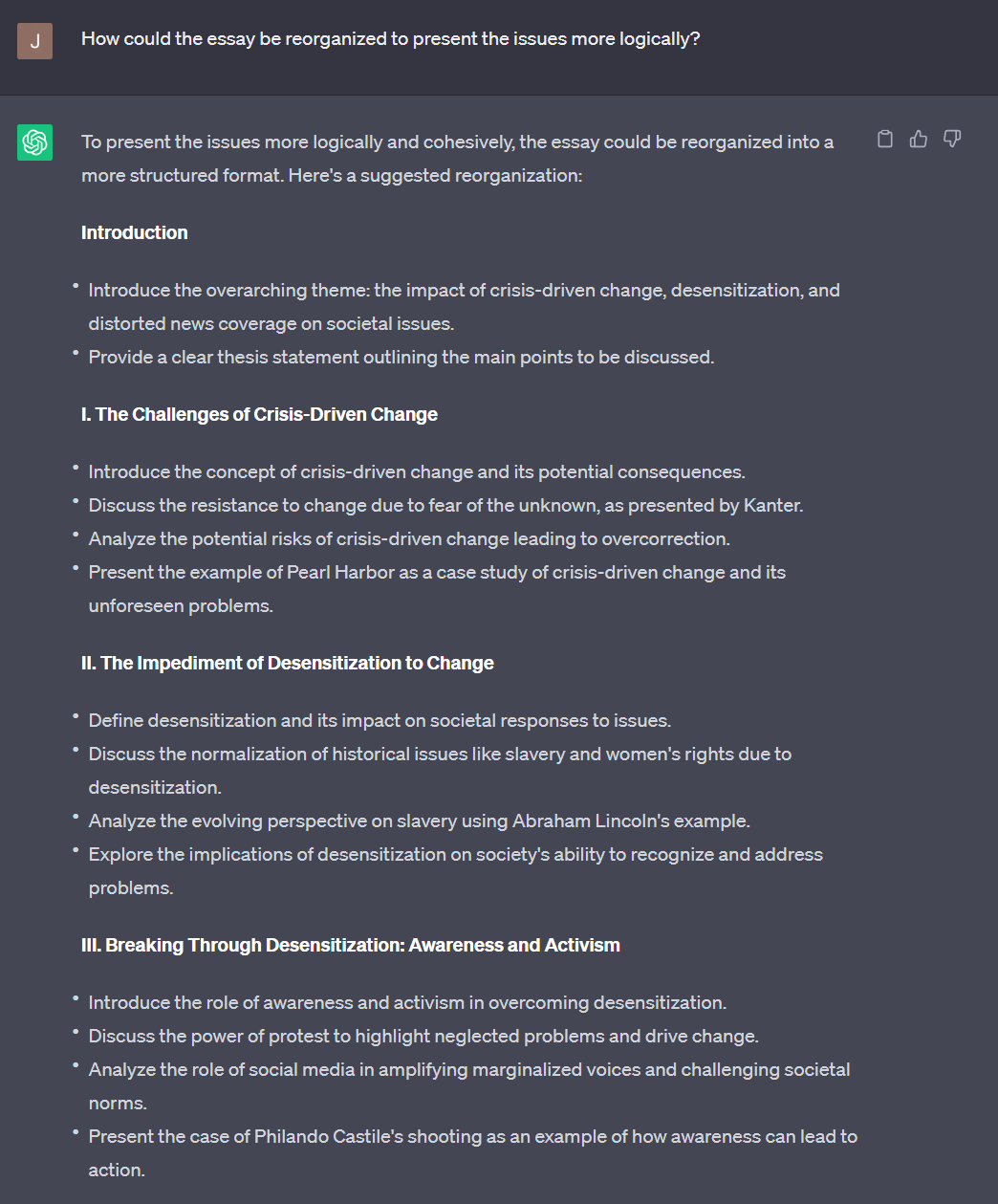

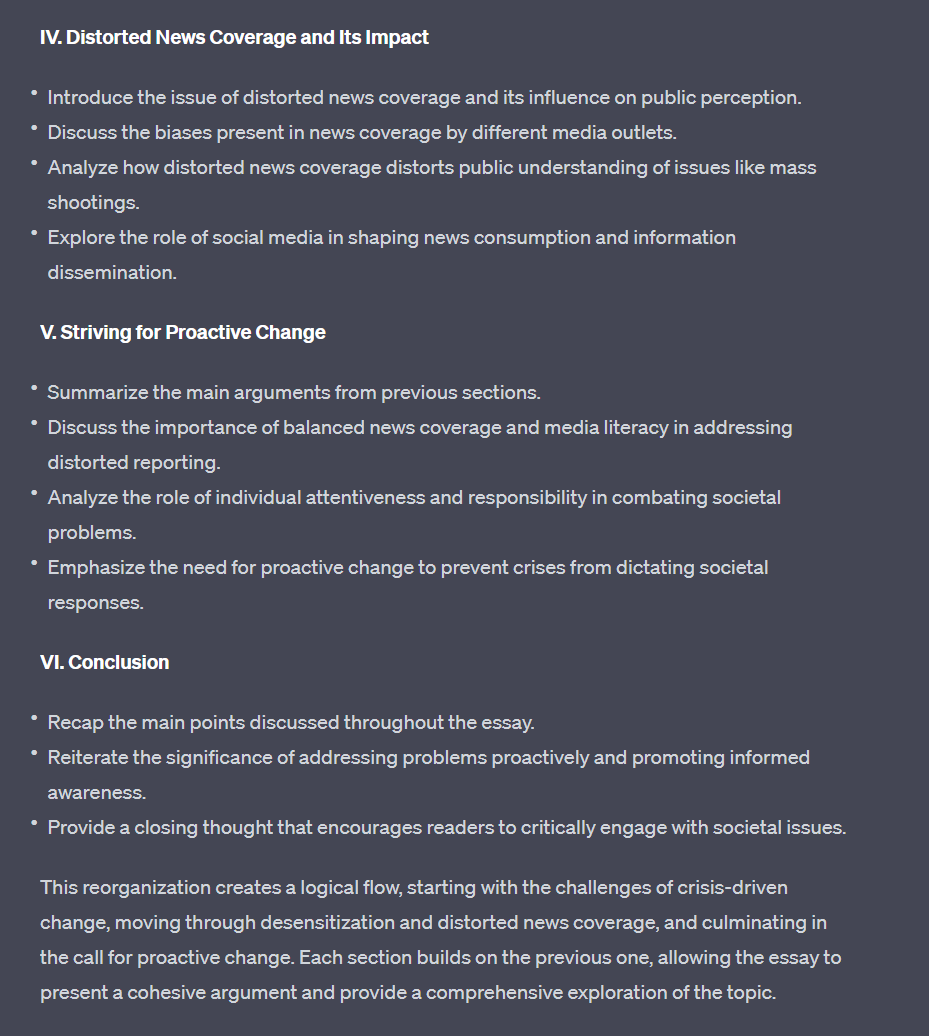

To do this exercise using AI, use the following steps. Figures 3.1 and 3.2 show an example of a seven-part reorganized outline generated by ChatGPT. In this example, ChatGPT has assigned specific examples from the original essay to different sections of the essay, which generally move from historical to modern contexts. Writers should regenerate the AI’s response multiple times to see which outline will meet the essay’s needs best.

- Enter the essay into the chat and ask the AI to make a reorganized outline. See Figure 3.1 for an example prompt.

- Regenerate the AI response until satisfied with the outline. Revise the generated outline to fit the essay’s needs if necessary.

- Cut up the essay into the outlined sections and arrange it within the new outline. Create new transitions as necessary.

The Physical Exercise

To do this exercise on printed paper, use the following steps:

- Make the font much larger and double-space the essay.

- Hack away with your favorite pair of scissors and lay all the pieces out on the floor.

- Rearrange the pieces until the sections fit together nicely, and then add new transitions as necessary.

Figure 3.1: Example of using ChatGPT to create a reorganized outline using the prompt, “How could the essay be reorganized to present the issues more logically?” (ChatGPT, personal communication, August 21, 2023.)

Figure 3.2: Continuation of figure 3.1. (ChatGPT, personal communication, August 21, 2023.)

Rewrite a Section (or the Whole Thing)

Many writers, such as the novelist and journalist Jennifer Egan, who won a Pulitzer Prize in fiction, will rewrite rather than simply revise. Jennifer Egan begins her writing process by hand on legal pads, where the initial draft of her novels form; then, she creates outlines for those drafts and rewrites (and rewrites the rewritten sections) in a succession of drafts that eventually create award-winning work (Mechling, 2011). Sometimes, rewriting an essay based on an outline of the first draft can help free writers from the limitations of previous drafts. Writers may choose to make an outline based on their topic sentences, each paragraph’s main idea, or they can use AI to help them generate and revise an essay outline, as seen in Figure 4.

For this exercise, writers will use the following steps to rewrite a section of their essay:

- Choose the section that needs the most work.

- Move quoted evidence from this section of the essay to a separate document. Consider exchanging these quotations for stronger ones.

- Rewrite this section of the essay without referring to the original draft. Reference the sources used for evidence as much as necessary.

Alternatively, writers may choose to rewrite their entire essay using the following steps, which will allow them to make dramatic structural improvements:

- Move quoted evidence to a separate document. Again, consider exchanging any weaker quotations for stronger ones.

- Consider either making an outline from your old draft or rewriting the essay completely from memory. When making an outline from a previous draft, do not hesitate to alter the outline before beginning the new draft.

- Reference only the sources and outline (if the writer made one) when creating the new draft.

Figure 4: Example of using ChatGPT to create an essay outline using the prompt, “Can ChatGPT create an outline of the provided essay?” (ChatGPT, personal communication, August 21, 2023.)

Local Revision

Writers use local revision to fix stylistic and grammatical errors, check citations, revise or cut individual sentences, and clarify minor details. This usually involves line edits during a final read-through before submitting an essay. Local revision is best done after global revision as a final step in the revision process. In Draft No. 4, John McPhee writes, “The way to do a piece of writing is three or four times over, never once” (2017, pp. 159). Ideally, drafts two and three should incorporate global revisions, and the final draft should focus on local revisions and line edits necessary to make the piece ready for submission.

Remember, when writers revise globally, they may cut or add large sections of writing to their essays. If a writer revises a section that they then cut in the global revision process, that writer has just wasted all the time spent revising the cut section. Also, if a writer adds a large section of writing during the global revision process but does not ever revise it locally, writers may end up leaving errors in that new section.

Local Revision Exercises

Be Concise: Cut Unnecessary or Distracting Sentences and Phrases

John McPhee writes, “Writing is selection” (2017, pp. 180). In order to begin a piece of writing, writers must select a topic, applicable sources, a first word, a first sentence, and so on. What writers choose to leave out of their essays is just as important as what they include. McPhee continues, “Ideally, a piece of writing should grow to whatever length is sustained by its selected material—that much and no more” (2017, pp. 180). This exercise requires writers to cut the excess.

For this exercise, writers will go through their essay while testing each sentence (or group of sentences) to ensure that they convey the maximum level of information with the fewest words possible. If a sentence does not add valuable information to the essay, writers should cut it. If a sentence can be shortened while conveying the same information in a similar tone, writers should shorten it. The presence of meaningless, excessively repetitive, or “fluffy” sentences will likely annoy readers and prevent them from reading further. Writers can also use AI to both identify sections of wordy prose and receive suggestions on how to reword those areas more concisely, as seen in Figure 5. In these examples, ChatGPT tends to simplify the sentence structure, which can also help readers understand concepts more easily, but ChatGPT sometimes uses inflated diction like “rife” and “exemplifies,” which might be off-putting to some readers.

It is, however, important to differentiate between guiding sentences, which are repetitive in nature, and other kinds of repetitive sentences, which might be termed “fluff.” Guiding sentences, such as topic sentences and conclusion sentences, reassert a writer’s main points and serve to guide the reader through the essay. These sentences help the reader navigate the essay, though these sentences may still give off a repetitive feel. To eliminate that feeling, writers should consider evolving their guiding sentences by adding nuance to their arguments as the essay progresses.

Writers should also search each section of their essays for ideas and arguments the reader might find distracting or irrelevant. Writers may choose to cut these sections entirely. Alternatively, writers may choose to shift the scope and trajectory to fully incorporate these sections into the essay; this will most likely involve revising guiding sentences, the introduction, and the conclusion.

If writers need to meet a certain word count and are worried about cutting parts of their essays, writers should consider further developing another aspect of their essays rather than clinging to repetitive or distracting sections. “Take a New Perspective” from the Global Revision Exercises section above can help writers lengthen their essays in productive ways.

Figure 5: Example of using ChatGPT to identify repetitive/redundant language using the prompt, “Where are some sections of the text that could benefit from concision?” (ChatGPT, personal communication, August 21, 2023.)

Track your Writing Habits

For this exercise, writers will focus on tracking their writing habits. Do writers use an excessive number of sentence fragments? Are writers susceptible to comma splices? Have writers confused their homonyms? Do writers tend to interrogate their readers with rhetorical questions? Writers might have received feedback on these habits from a writing instructor, tutor, or peer. Word processors might be underlining them, or writers might even be noticing these habits themselves during revision. Writers may even ask AI to identify grammatical trends in their writing, as seen in Figure 6. Asking AI to analyze writing trends can be particularly helpful because the AI will find tendencies that peers or autocorrect may miss, like the use of unnecessarily long sentences in the example below. Writers may also consider asking ChatGPT to identify a specific number of errors within the essay to avoid receiving an overwhelming list of things to fix.

Writers should choose one—and only one—writing habit they want to improve. First, writers will need to research how to correctly use the grammatical function (if the habit involves a grammatical function). The Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation is an excellent comprehensive source for learning about grammatical functions. After writers have done their research, they should read through their drafts and fix every issue stemming from the chosen writing habit. Writers should not worry about anything else and keep their focus on this one habit. Word processors and programs like Grammarly can be very helpful for identifying issues, but they cannot identify every issue and are occasionally wrong.

Figure 6: Example of using ChatGPT to identify writing tendencies using the prompt, “What incorrect grammatical tendencies does the text make?” (ChatGPT, personal communication, August 21, 2023.)

Reflection

Now that writers have engaged in a combination of global and local revision exercises, they should take time to reflect on the outcomes of those exercises. Writers should consider how each exercise altered their essays. If one exercise was particularly helpful, writers may choose to incorporate that exercise into their future revision processes. If one exercise was less helpful, writers may choose to either adapt the exercise in the future to better fit their needs, or to try other revision exercises to see which ones offer the best help during the revision process.

Questions to Guide Reflection and Discussion

- How can rewriting sections or entire essays from memory or an outline improve the revision process and the final piece?

- Reflect on the effectiveness of cutting unnecessary sentences or phrases for conciseness. How does this impact the clarity and impact of your writing?

- Discuss the benefits of using AI tools for identifying weak areas in your writing, such as redundant language or incorrect grammatical tendencies. How can these tools complement traditional revision practices?

- Explore the concept of global versus local revision exercises. How do these different approaches address various aspects of the writing and revision process?

- Consider the role of time in the revision process as suggested by John McPhee. How does allowing time between drafts enhance the writer’s perspective and potential for improvement?

References

Adler-Kassner, L., and Wardle, E. (eds.). (2016). Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of writing studies. Utah State University Press.

Beatman, A., and Samantha, S. (2023). 15 Tips to Become a Better Prompt Engineer for Generative AI. Microsoft Tech Community. https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/t5/ai-azure-ai-services-blog/15-tips-to-become-a-better-prompt-engineer-for-generative-ai/ba-p/3882935.

Del Barco, M. (2023). Striking movie and TV writers worry that they will be replaced by AI. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2023/05/18/1176806824/striking-movie-and-tv-writers-worry-that-they-will-be-replaced-by-ai.

Lamott, A. (2019). Bird by bird: Some instructions on writing and life (25th anniversary ed.). Anchor Books.

McPhee, J. (2017). Draft No. 4. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Mechling, L. (2011). How do you write a great work of fiction? Jennifer Egan explains the steps. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-SEB-64384.

Summary of the 2023 WGA MBA. (2023). Writer’s Guild of America East. https://www.wgaeast.org/guild-contracts/mba/summary-of-the-2023-wga-mba/.

WGA negotiations—Status as of May 1, 2023. (2023). Writer’s Guild of America East. https://www.wgaeast.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/05/WGA_proposals.pdf-link_id=1&can_id=a09a8f649a17770eaee0da640da3fdc0&source=email-wga-on-strike-2&email_referrer=email_1901631&email_subject=wga-on-strike.

- The essay fed to ChatGPT to retrieve this example (and all subsequent examples) was written by Jacob Taylor. This image (and all subsequent images) was captured by Jacob Taylor. ↵