28 Creating Constitutions with ChatGPT

Julia M. Gossard

Abstract

This chapter explores how students used ChatGPT to construct constitutions in a course on the history of the Age of Revolutions. Student responses, the product, and instructor implications and critiques are included.

Keywords: generative AI, assignment, creation

In February 2023, as conversations about ChatGPT and other generative artificial intelligence (A.I.) tools became commonplace, I asked my honors students in HONR 1320 what they thought of generative A.I.1 Most students commented that they believed it was promising, though limited in its current capabilities. Everyone in class that day, including me, said they had experimented with ChatGPT, Dall-E, or another generative A.I. tool by that point. Many expressed wonderment and anxiety about artificial intelligence’s eventual capabilities, recognizing that it seemed like the technology was still in development. I asked my students if they thought generative A.I. could possibly serve as a tool—like the calculator—in the not-too-distant future, helping people complete specific tasks but not necessarily replacing human knowledge. The students were divided. Some agreed that generative A.I. might be a helpful tool, whereas others playfully mused they were preparing for their future artificial intelligence overlords.

Most of my colleagues in the humanities and social sciences were understandably panicked about generative A.I., recognizing that there was a high potential for academic integrity violations on written assignments. There is also little way to accurately identify its use on these assignments, making many anxious about how students might use the technology for dishonest purposes. The conversation with my students, however, helped me realize that instead of panicking about generative A.I. in the humanities classroom, I should experiment with how to harness the power of ChatGPT to encourage deeper analysis and application of learning materials. An exercise that I have done for several semesters as a culminating experience where students create their own constitutions came to mind. Since students were open to discussing their use of and feelings towards ChatGPT, I revised this group activity to have multiple parts, some performed by students in small groups, and some performed by OpenA.I.’s ChatGPT on the last day of the semester.

Creating Constitutions Curricular Background

Students in HONR 1320 study the history of the Age of Revolutions (1750-1820) through role-play simulations of the American and the French Revolutions. Adopting a character from each revolution, students write papers, give speeches, and negotiate all according to their character’s desires. These simulations provide them a unique experience into the mindset and issues of the eighteenth century. On the last day of the course, students reflect on the lessons they learned about representative government by writing their own constitutions. Students draw inspiration from the Enlightenment, the U.S. Bill of Rights, and the Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen. In small groups, they negotiate how to define citizenship, natural rights, and representation in group-created constitutions.

Students find this exercise both exhilarating and quite difficult. They are excited to apply what they have learned throughout the semester, getting to write a governing document that appeals to their main concerns in the present. Almost all students incorporate elements from Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Locke’s understandings of the social contract, highlighting how they understand the necessity for government and law. Students, though, are often inspired to rewrite pieces of the American and/or French constitutions that they do not agree with (or think could have better definitions). Many groups’ constitutions, for instance, explicitly include references to all gender identities, races, and sexual identities. This element of present-day concerns over rights and equal access to the law provides clear and resolute definitions on who constitutes “all” in the students’ governing documents.

Revised Instructions

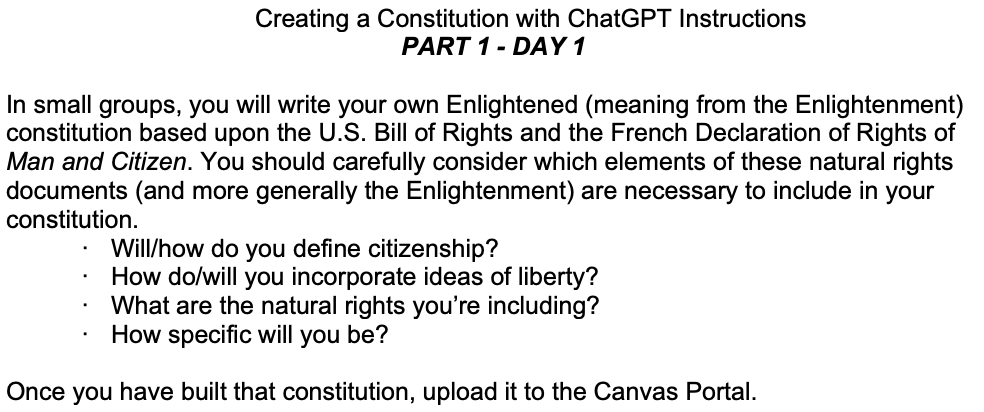

The genre of constitution creation lends itself very well to experimenting with ChatGPT. Since the original assignment centers around creating something new from text-based, mostly accessible online sources, I knew ChatGPT was going to be capable of producing work similar to what my students might produce. When experimenting with generative A.I. such as ChatGPT, it is important to recognize the limitations of the technology. Using DALL-E, a primarily visual generative A.I., for instance, would not have produced the right kind of result that would be easy to compare. As I revised the assignment, I thought carefully about some key questions. I was curious how ChatGPT would perform given the prompt verbatim and how the result might adapt and change through additional prompting, requests for clarifications and additions, and other demands from student users. I was also interested to see how students’ own constitutions would compare to the ChatGPT-generated constitutions. Would there be considerable overlap, noticeable departures, or observable influence from contemporary political discussions of contested natural rights in both? Given these questions, I revised the constitution activity. Students first created constitutions as normal in small groups, using the instructions below.

Figure 1: Instructions for Student-Created Constitution Activity

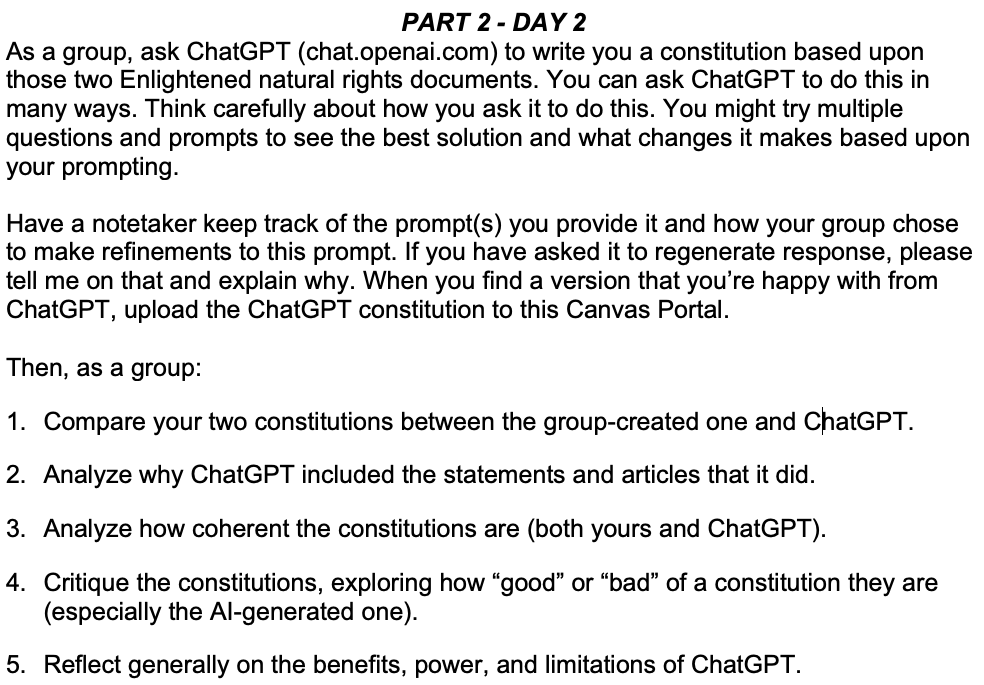

Then, I turned the constitution writing activity into a generative A.I. exercise to see what students would receive for answers and how they would interpret the constitutions that ChatGPT developed. After writing their own constitution, each group had to come up with a prompt (or a series of prompts) to give to ChatGPT to write a constitution. The group could put in as many prompts and additional details as they wanted into ChatGPT until it created a constitution that the group found acceptable. Then, as a class we discussed how their group-created constitutions compared to their ChatGPT-generated constitutions.

Figure 2: Instructions for ChatGPT-Created Constitution and Analysis

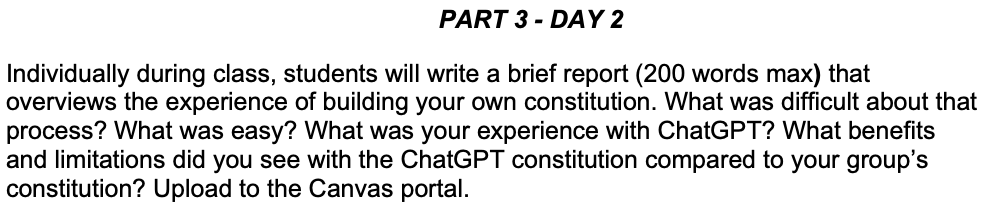

Finally, I also asked students to provide individual short (500 words or less) written reflections about their experiences after the class session to better understand students’ involvement with and feelings towards generative A.I. The results were illuminating for me and my students.

Figure 3: Instructions for Student Written Reflection on ChatGPT

Student Responses

Nearly every student commented that the A.I.-generated constitutions were well written. Students said the generative A.I. governing documents were “short and sweet” and “not overly complex.” In particular, the ChatGPT-created constitutions left little room for ambiguity. Each provided clear definitions on who constituted a citizen. For example, two of the constitutions specifically stated that “every human being in the country regardless of race, gender identity, religion, creed, sexuality, and class” is a citizen. This clarity is something many students recognized could have been to the advantage of American and French framers. One student remarked that A.I. “could help remind us to be specific” since a lack of specificity “can often do extreme damage” in the long run.

Despite enjoying the specificity that ChatGPT provided, students noted some important challenges and oddities of the A.I.-generated constitutions. Nearly every student remarked in their reflection essay that ChatGPT was rather unimaginative, simply plagiarizing entire articles from either the French Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen or the U.S. Bill of Rights. As one student wrote, “The act of using ChatGPT was problematic…it would just plagiarize the U.S. Constitution without any changes whatsoever.” Another stated, “…it plagiarized a LOT.” When reflecting on the specificity used to describe a citizen, one student remarked they were “pretty sure ChatGPT copied the Civil Rights Act of 1965 and various equal opportunity employment statements.” Students were quick to see how ChatGPT routinely plagiarized, and they critiqued it for doing so. Some students were quite harsh in their condemnation of ChatGPT explaining that they felt that generative A.I. was going to “dumb everyone down” and lead to “cheaters coming out on top.” With honors students, it was no surprise to see this type of viewpoint in regard to academic dishonesty.

While students were not necessarily surprised by the omnipresence of plagiarism, they were frustrated by ChatGPT’s lack of ingenuity. A student wrote they “hoped ChatGPT would whip up a document that was unique, fresh, exciting, new and young but its [sic] basically what we already have.” Unless students provided additional prompts and directions, the resulting constitutions were largely bastardized versions of current governing documents. Many students had hoped that generative A.I. would be inspired by these documents and create new articles about human rights, citizenship, and representation but it simply “copy and pasted a lot of articles” from these foundational documents.

One student provided a particularly keen analysis of why ChatGPT plagiarizes, writing that “it does not actually understand philosophy.” They explained that “generative A.I. does best with algorithms, formulas and equations thus why it can replace repetitive jobs like coding, but it is completely unable to conceptualize and truly understand or innovate.” This student is correct for now. It does not understand and think on its own. ChatGPT makes it abundantly clear when prompted to take a position or defend a particular thesis that it cannot. Instead, it usually provides a middle of the road argument or a “both sides” presentation of a particular topic. Students saw this on full display with their plagiarized constitutions.

Yet, several students observed that at the same time ChatGPT plagiarized, the generative A.I. response did have a progressive slant in some of its content. A student wrote, “supposedly A.I. is supposed to give you an unbiased response, however, I am beginning to think that is not the case.” According to their reflection, their result was “strangely political,” demonstrating twenty-first-century biases. ChatGPT seemed to “back away from controversial issues,” leaving out mentions of the “right to bear arms” in all of the class’s constitutions. Curiously, as well, three of the A.I.-generated constitutions made note of data-privacy as a natural right. None of these groups made note of that as a natural right that should be included. Thinking about the online source base that ChatGPT gleans information from, data-privacy likely popped up as a current conversation regarding twenty-first-century rights. Students mentioned they were surprised to see such strong twenty-first century rhetoric added to the constitution “without any prompt to be progressive.” This helped students recognize that even though generative A.I. claims to be unbiased, the sources it draws upon can and are biased, occasionally resulting in bias appearing in answers.

This exercise demonstrated the need to continue teaching students strong critical thinking and analytical skills. Students must continue to carefully learn how to evaluate information they consume. Students employed their digital literacy skills to analyze that the generative A.I. was receiving only partial information from sources easily available on the internet. But, if they had not been taught careful, close reading and analytical thinking skills, they may not have recognized the limitations of generative A.I.

Instructor Reflections and Implications on Present Use

As an instructor, this exercise gave me immense hope and excitement about the future of generative A.I.. When doing this activity again, I would build in more time to work on the constitutions. Fitting all pieces of this activity into a 75-minute class left little time for students to reflect in the moment on their experiences and to deeply compare their documents. Instead, I will break this up into two class sessions: one day for their group-created constitutions and one day for the A.I.-generated constitutions. On the first day, I will create a gallery walk or a shared Google Doc (depending upon course delivery modality) for students to share their groups’ constitutions so the class can note the similarities and differences between groups. Taking inspiration from a student who reflected, “I wish we could have had more time to talk about the impact of generative A.I. on the humanities and social sciences,” on the second day I will allow for additional discussion about technology, the humanities, and critical thinking. Having these kinds of discussions with students are important. Instructors can better understand how their students use generative A.I.

Most importantly, this exercise illuminated the need to teach with A.I., especially in the humanities. From this project I became interested in studying how (and how much) college students use and interact with ChatGPT. In preliminary findings from my study “ChatGPT in the College Classroom,” (IRB #13569), 100 out of 102 students anonymously reported that they use generative A.I., especially ChatGPT, to help them complete assignments. Most of these students explained they do not engage with generative A.I. as a full replacement for their work. Rather, an application like ChatGPT helps lay a foundation for students to provide additional analysis and detail. It can cut down on their workload or help them get started on a concept or assignment they find particularly daunting. This data along with my experience with creating constitutions in HONR 1320 compelled me to realize that I must help students learn how to appropriately use these tools.

I have now embedded additional generative A.I. assignments into my HIST 1110: European History from 1500 general education course that enrolls 180 students each semester in an online, asynchronous capacity. In these assignments, called “Apply Knowledge Activities,” students critique, revise, and use generative A.I. to answer specific writing prompts in 150-200 words using primary and secondary source evidence that they take from class materials. This allows them to practice several important skills: close reading, primary source selection, secondary source selection, primary source analysis, secondary source analysis, and short argumentative writing. Students are drawn to these assignments, with a nearly 90% completion rate Summer 2023 and Fall 2023. This is 14 points higher than a traditional assignment completion rate in this course. In these Apply Knowledge Activities, students provide thoughtful critiques to the A.I. short answers and essays. In the historical discipline, specificity is key to providing good source analysis. Students often reflect that ChatGPT only provides a superficial answer that lacks detail and evidence from sources. They often fully rewrite the short answers ChatGPT wrote and include specific details drawn from assigned readings, lectures, and activities that demonstrate their deep engagement with material covered in class. Their revised answers are either inspired by or partially written by ChatGPT, but it showcases their own analysis and incorporates keen source selection. Through these assignments, students learn how to use generative A.I. to their advantage while also considering its limitations.

For instructors who may be interested in teaching with generative artificial intelligence, I encourage you to start small. As I did with the “Creating Constitutions” assignment, find an existing assessment that serves a role in your course. Consider how you might slightly tweak, revise, or add to the assignment by adding a ChatGPT or artificial intelligence component. This could be either using ChatGPT as a tool, critiquing its product, or even comparing ChatGPT’s written products to that of Google Bard. Whichever you choose, make sure you have explained to students why you are integrating a generative A.I. component into the assessment. While students seem drawn to generative A.I. assignments, it may become bothersome or tiring if it feels like the technological aspect of the assignment is simply shoehorned into an assessment.

Just as how mathematicians rely upon a calculator, we may, in the not-too-distant future, see generative A.I. as a comparable tool for writing and analysis. Students may use generative A.I. as a crutch but if they understand how to use it well, they can substantially benefit. Yet, because generative A.I. is not yet capable of critical thinking in the way that humans can, students must know how to use the tool to their advantage. Human academic abilities—critical thinking, analysis, and even beauty in prose—remain essential.

Questions to Guide Reflection and Discussion

- How does using ChatGPT for creating constitutions engage students with historical and political concepts differently than traditional methods?

- Reflect on the balance between AI-generated content’s specificity and creativity. How does this impact students’ understanding of constitutional principles?

- Discuss the implications of AI’s tendency to “plagiarize” existing documents. What does this reveal about AI’s current limitations and potentials for learning?

- How can educators utilize AI tools like ChatGPT to foster critical thinking and analytical skills in evaluating the sources and content generated by AI?

- Consider the ethical and practical aspects of integrating AI into historical and civic education. How can this shape students’ perceptions of technology’s role in society?