3 How Adult Education Can Inform Optimal Online Learning

David S. Noffs and Kristina Wilson

Author Note

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to David S. Noffs and Kristina C. Wilson, Northwestern University, School of Professional Studies, Abbott Hall, 710 N. Lake Shore Dr. Suite #320, Chicago, Illinois 60611.

How Adult Education Can Inform Optimal Online Learning

David’s Story

I first met Krissy Wilson in 2015 when I was asked to design a new graduate course at Northwestern University on learning environment design. Krissy was part of the talented Distance Learning team in the School of Professional Studies. I was a teacher, instructional specialist, and reluctant learning management system administrator at an arts-based city college where I had worked for almost 15 years.

During the development of the course, I created a one-week-long module titled “Preparing for the Apocalypse: Using the Internet to Survive Downtime.” In my introductory video of the week’s subject matter to the class, I said, “I know the title of this module sounds very dramatic, and I wanted it to be. Being an educator in the information age requires careful and critical reflection about how we view technology and the relationship of people to technology.”

Little did I know how prophetic this title would turn out to be. While I was referring to intranets and school learning management systems at the time, I never dreamed it would be the actual school itself that would be shut down, yet in both scenarios the message that the internet operates as a communication safety net holds true.

I was fortunate enough to be able to join the Distance Learning team at Northwestern in 2017 as a learning designer and still teach Learning Environment Design. Krissy and I have teamed up on several research projects and presented at conferences as we explore optimal online learning and emerging pedagogies.

Krissy’s Story

I got to know David Noffs first as a faculty member in the Master in Information Design and Strategy program in the School of Professional Studies at Northwestern University. Before he joined the Distance Learning team as a learning designer, he was already well-known to all of us as “power faculty,” the kind of instructor who took online course development both seriously and creatively and always showed up for professional development.

While I knew David first as a faculty member and then as an instructional designer, my path was the inverse of his. Prior to being a learning designer, I was a part-time instructional designer in the adult and continuing studies college at another private university in Chicago, a position I grew into from a student elearning content developer position. It was only after David and I had been working together for a few years that I began to teach professional writing at another Chicagoland university. Although I had a perennial interest in education, I was formerly a teaching assistant, tutor, or writing fellow; now, as the news of COVID-19 broke and we all sheltered in place to begin working remotely, I found myself teaching my first course solo.

Prior to COVID-19, our team was working successfully with one remote day per week. Many of the faculty members we partnered with on course developments were not in the Chicagoland area, and we used video conferencing tools, shared documents, webcams, headphones, microphones, and the learning management system to develop coursework without ever meeting each other in person. We thought we had it figured out. Our team joked that we had no need for an office, that we could do our jobs entirely remotely. Why didn’t we? Why shouldn’t we?

Despite the circumstances, David and I have continued to collaborate on research projects and conference presentations, and I am grateful for his guidance and support.

A Note on Form and Style (The Medium is the Message)

In this chapter, we rely heavily on reflection and conversation. It is intentionally autoethnographic, as we demonstrate the values espoused by the theorists we cite. For example, the reflective stories we tell hark back to Mezirow’s (2009) priority to “[Encourage] a reflective practice” (273). Consider bell hooks’ 1994 conversation with Ron Scapp in Teaching to Transgress a model for our tone (pp.131–165). As we participated in a university-wide online teaching practicum this summer, we held conversations with faculty that helped to develop the framework we share here. In other words, the form and structure of this chapter speak to the content, and honors not only the educators whose research we rely on but also our own recent experiences teaching online in a global pandemic.

The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Optimal Online Learning

The idea behind this chapter began when the instructors at Northwestern University’s School of Professional Studies were in the process of grading final projects and exams from the Winter 2020 quarter. As part of the Distance Learning team (along with Northwestern IT, the library, the Searle Center for Advanced Learning and Teaching, and other faculty support staff across campus), we prepared to train over 1,000 faculty members in little over a week on how to move their course content, rethink their activities, and start teaching online for the spring quarter. We were witnessing and were a part of “The Great Onlining of 2020,” as George Siemens (2020) tweeted on March 11th.

And it wasn’t just Northwestern that moved rapidly; according to a survey conducted by Bay View Analytics and published in Inside Higher Education (Ralph, 2020), 90% of American colleges and universities had about a week to move their courses, instructors, and students online. As a result, the quality of instruction understandably suffered. For example, 80% of instructors used synchronous video to teach, while 48% said they lowered their expectations for the amount of work students would be able to do. Another 32% said they had “lowered the expectations about the quality of work that my students will be able to do.”

Several months into The Great Onlining of 2020, there appears to be a consensus among many academic researchers and scholars that the move to emergency remote teaching, now commonly referred to as ERT (Hodges et al., 2020), has created a two-tiered system of online education: ERT courses and thoughtfully designed online courses. We would like to place ERT on the lower tier and optimal online learning (OOL) on the upper tier. The speed with which thousands of courses were moved online is staggering. Development cycles that are normally six months were reduced to mere weeks. While ostensibly only a temporary or emergency fix, this has led to the inevitable comparison between online learning and face-to-face learning.

Hodges et al. (2020) warn us that “Online learning will become a politicized term that can take on any number of meanings depending on the argument someone wants to advance” (para. 3). Trollish articles have already appeared with sweeping and uninformed headlines. Some examples include “Trump Says, ‘Virtual Learning has Proven to be Terrible,’ Threatens Cuts to Federal Funds” (Singman, 2020); “The Results Are In for Remote Learning: It Didn’t Work” (Hobbs and Hawkins, 2020); and “The Real Reason Why The Pandemic E-Learning Experiments Didn’t Work” (Christensen, 2020), to illustrate just a few. The usual theme is that distance learning does not work or is inferior.

Many universities scrambled to ramp up their online preparedness by mandating summer boot camps for full- and part-time faculty. These practicums, in which we have participated as consultants, are intended to address the obvious deficiencies in ERT courses. However, despite these efforts, there is still a gap in the underlying practice of online instruction that has become exposed under these extraordinary conditions.

Even under the best of circumstances, how can online learning possibly fill the needs of students yearning for human contact and a sense of college community? While virtual teaching can present the curriculum, how will schools address the social, emotional, and experiential needs that physical campuses offer?

But what is missing from ERT? Below is a list of some of the missing components:

- Learner-centered teaching

- Community building

- Experiential learning opportunities

- Opportunities for critical thinking

- Meaningful self-reflection

- Transformative learning

While many educators may shrug their shoulders at this dilemma, leading adult educators and philosophers such as Eduard Lindeman, John Dewey, Jane Adams, Cyril Houle, Jürgen Habermas, Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, Malcolm Knowles, Paulo Freire, bell hooks, Jack Mezirow, Maryellen Weimer, Stephen Brookfield, Rena Palloff, and Keith Pratt have long extolled the virtues of community building and creating learner-centered cultures in learning communities.

Challenging undergraduates, for example, not only to participate in but to create and lead virtual communities can fill some of the voids laid bare by half-empty campuses and student groups struggling to meet socially. By leveraging extensive research conducted on the roles of online learners and teachers, and by making self-governance and action learning pillars of online learning, we may be able to nurture a new age of online learning, informed by adult education theory.

Before we begin discussing adult education strategies that can improve the online learning experience, we felt that it may be helpful to provide our own glossary of key elements we will reference often, specifically in the context of online learning.

Glossary of Key Elements Used in OOL

Learner-Centered Teaching

The subtle yet important difference between learner-centered teaching and student-centered teaching can be confusing. Maryellen Weimer (2002) persuades us to lean toward the former in our own design and teaching practice. She points out that the term student-centered teaching places an emphasis on student needs rather than learning needs. Student-centered teaching implies a paradigm where education is a product served up by faculty to student consumers. Providers of such student-centered teaching are more likely to include LinkedIn Learning authors and YouTube channel creators. Learner-centered teaching, on the other hand, “focuses attention squarely on learning: what the student is learning, how the student is learning, the conditions under which the student is learning, whether the student is retaining and applying the learning, and how current learning positions the student for future learning” (p. xvi).

Community Building

Community building is a core tenet of adult education. Habermas’ (1984) critical theory of communicative action and emancipatory knowledge along with Mezirow’s (1991) theory of transformative learning hinge upon creating a reflective community of learners.

Martin Dougiamas, who wrote the original code for the Moodle Learning Management System, and Peter Taylor (2003) describe the online pedagogy behind their work to create an open-source learning management system as a natural progression based upon social constructivism and social constructionism. Through the perspectives of collaborative discourse and the individual development of meaning, “learners are apprenticed into ‘communities of practice’” (p. 3).

Moreover, Palloff and Pratt (2007) organize the elements that must be present to support the formation of online communities into three groupings: people, purpose, and process. They assert that “the outcome of a well-constructed, community-oriented online course is reflective/transformative learning” (p. 17).

Experiential Learning

John Dewey, Confucius, and a host of educators and scholars agree that a student learns more from doing than from only listening or seeing. Experiential learning acknowledges that people learn from experiencing a new activity or solving a problem. Kathleen Cercone (2008) combines many prominent adult learning theories in her compilation of precepts that include Knowles’ (1984) principles of andragogy and Mezirow’s (2000) transformative learning theory. The following are selected recommendations from her list:

- Adults need to be actively involved in the learning process.

- Adults need to see the link between what they are learning and how it will apply to their lives. They want to apply their new knowledge. They are problem-centered.

- Adults need to feel that learning focuses on issues that directly concern them and want to know what they are going to learn, how the learning will be conducted, and why it is important. The course should be learner-centered vs. teacher-centered.

- Adults need to test their learning as they go along, rather than receive background theory.

- Adult learning requires a climate that is collaborative, respectful, mutual, and informal.

- Adults need to self-reflect on the learning process and be given support for transformational learning.

- Adults need dialogue and social interaction must be provided. They need to collaborate with other students (pp. 154–159).

Transformative Learning

Mezirow’s theory of transformative learning was first published in Adult Education Quarterly in 1978. After decades of discussion and refinement, Taylor distilled the theory into six key elements to introduce Transformative Learning in Practice (2009), in which Mezirow acknowledged it as “an evolving theory” with “a coherent group of general principles” (p. 18). These principles include individual experience, critical reflection (see Self-Reflection), dialogue, holistic orientation, awareness of context, and authentic relationships, and typically begin with a “disorienting dilemma” (p. 19).

A case study by Dirkx and Smith (2009) in the same text anticipated pushback to emergency remote teaching online, observing that “educational technology in general, and online or e-learning in particular, seems an odd location in which to look for and consider the poetry and mystery of transformative learning” (p. 57). Faculty have made transformative experiences happen in their face-to-face classes and are now working to emulate those experiences online; however, they are hampered by the assumption that transformative learning is more effective when students are all in the same physical location. Dirkx and Smith also assert—and we agree—that “online environments provide evocative contexts for . . . dimensions of adult learning,” including and beyond the “rational, reflective, and instrumental” (p. 58).

Self-Reflection

Taylor acknowledges self-reflection as a vital component of the transformative learning model and defines it as “Questioning the integrity of deeply held assumptions and beliefs based on prior experience” (p. 7). He goes on to describe critical reflection as a skill that students can develop and suggests that instructors create opportunities for three kinds of reflection: “content (reflection on what we perceive, think, feel, and act), process (reflecting on how we perform the functions of perceiving), and premise (an awareness of why we perceive)” (p. 7). Taylor, citing Kreber (2004), considers premise reflection crucial for instructors themselves, in order to raise awareness of “why they teach [more] than how or what to teach,” (p. 8) a goal of this chapter.

In 2020, the Great Onlining and move to ERT functions as Mezirow’s “disorienting dilemma,” the conduit for premise reflection for both instructors and students. If we are to change our own assumptions—and others’ assumptions—about the potential for optimal online learning, it will require self-examination. For many, this could be a fraught process. We are not just questioning the theories that guide our instructional decision-making; instead, we embody our pedagogies and are faced with examining, critiquing, and ultimately changing ourselves. hooks observes, “one of the things blocking a lot of professors from interrogating their own pedagogical practices is that fear that ‘this is my identity and I can’t question that identity’” (hooks’ emphasis, p. 135).

Critical Thinking

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2018) succinctly defines critical thinking as “careful thinking directed to a goal,” (para. 1) but critical thinking still escapes easy definition for most academics. For a brief glimpse into its complicated history with adult education, consider that Dewey’s 1910 coining of the term cited anachronistic examples. Well-known educational tools such as Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956) rely on critical thinking theory to support their frameworks, but they also pull critical thinking theory apart, as in Ennis’ “proposed 12 aspects of critical thinking as a basis for research on the teaching and evaluation of critical thinking ability.” As recently as 2019, scholars have sought to continue classifying and structuring critical thinking models to make them more approachable, comprehensive, and usable. (Recursively, academics also study other academics’ perceptions of the definition of critical thinking.)

So, while we acknowledge that any single definition of critical thinking may be contested, it is important to distinguish it from self-reflection. They share an origin in Dewey, who commonly interchanged the terms “critical thinking” with “reflective thinking.” While critical thinking and decision-making may be informed by past personal experience (hence, reflective thinking), critical thinking asks students to respond in the present moment. Given a situation—either in real life, or in a case study or scenario—what would you do?

In the context of The Great Onlining of 2020, critical thinking is a term we must not only personally define, but a skill we must personally cultivate. In order to successfully interpret and modify activities and materials from a face-to-face course for online learning, we must think critically. If we are literally and figuratively extending the boundaries of our teaching, we must return to our basic Stanford definition and exercise careful thinking with a goal in mind. By careful, we don’t mean tentative; instead, we mean with care.

Our shared goal as instructors is optimal online learning, and we can create activities and assignments designed to develop critical thinking skills in our students to help accomplish that. However, it is not enough to coach students without developing these skills in ourselves.

In 2018, Christopher Schaberg wrote an opinion piece for Inside Higher Ed titled “Why I Won’t Teach Online,” insisting that he could not develop meaningful relationships with students or successfully hold a seminar discussion, complete with “awkward silences.”

Imagine our surprise when, in September 2020, he published another opinion piece titled “Why I’m Teaching Online.” Among his reasons? “It’s a chance to learn,” he writes. “I can use this time to try new teaching methods and to make my pedagogical values newly vivid.” He goes on to describe how he has students collaborate using Google Docs and is “teaching media literacy while also using the internet as a living archive, ready for interpretation and critical thought” (Schaberg 2020).

This experience serves as an excellent example of how an instructor may use critical thinking to examine their own pedagogy, and in turn create new opportunities for critical thinking among students. (And, to draw continued connections, demonstrates the power of the disorienting dilemma when paired with self-reflection.)

Optimal Online Learning Strategies

Now that we have provided an overview of the difference between ERT and OOL and a glossary of key elements for effective teaching guided by adult education theory, we will provide some practical examples and strategies for OOL.

Table 1 shows how adult education imperatives we have discussed in this chapter may or may not be addressed in online learning environments.

| Adult Education Imperative | ERT Approach | OOL Approach |

| Teacher-Centered Learning | ERT classrooms often resort to Freire’s (2010) “banking model” by relying on synchronous “webcam lectures.” | OOL classrooms leverage bell hooks’ (1994) “teaching to transgress” model, encouraging students to question assumptions and power relationships. |

| Community Building | ERT classrooms pay lip service to the community of online learners. | OOL celebrates communities and individual learners, their life stories, and builds on Knowles’ (1980) idea that learners like to solve specific problems that are relevant to them and allow them to be part of the planning process. |

| Experiential Learning | ERT classrooms lack opportunities for open dialogue and experiential learning. | OOL classrooms nurture facilitated asynchronous discussions in which students feel that they can speak openly, sharing life stories and engaging in consensus building. |

| Critical Thinking | ERT classrooms tend to be outcome-driven, and critical thinking is viewed as too difficult to achieve. Proctored virtual exams represent rigorous learning. | OOL values critical thinking by having students openly share their unique perspectives in group settings, engage in problem-solving activities, and debate-style discussions. Solving complex problems represents rigorous learning. |

| Self-Reflection | ERT classrooms lack opportunities for self-reflection. | OOL encourages self-reflection through reflective essays, online journaling, ePortfolios, and other strategies |

| Transformative Learning | ERT classrooms lack opportunities for transformative learning. | OOL strives for “transformative learning” by having students challenge one another respectfully through role-playing and allowing for difficult discussions. Disorienting dilemmas are welcome (Mezirow, 2000). |

While we hope Table 1 helps clarify the difference between ERT and OOL, we feel it is important to go from the theoretical to the practical. The following sections show how the OOL strategies described above can be applied to virtual classrooms.

Going from Zoom Lectures to Asynchronous Discussions

One of the most common features of ERT is the over-dependence on synchronous learning and lectures through the use of web conferencing software such as Zoom and Webex. During our work with faculty members over the spring and summer of 2020, we were part of a team that struggled at times to convert new online teachers to the practice of asynchronous discussion boards. Ironically, our struggles during the pandemic reflect a struggle that adult educators have had for the better part of the 20th century and now continuing into the 21st century.

Paulo Freire (2010) introduced his “banking model” of teaching in his seminal work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. While adult educators, researchers, and social activists like John Dewey, Eduard Lindeman, and Jane Adams had long extolled the virtues of engaging learners in the lifelong process of education rather than solely lecturing to them, Freire drove home the notion that learners were not passive vessels waiting to be filled with information the teacher would share at the appropriate time and place of learning.

According to Freire, “In the banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing” (p. 72).

But while Freire was challenging state-controlled education systems after being exiled from his native Brazil in the late 1960s, his ideas resonated with adult educators who supported a more humanistic and liberating approach to education throughout North America and Europe, in particular. Moreover, his approach reinforced a trend in education in the United States that had been growing since the mid-20th century. Namely, an increasing focus on the learner as a “unique individual in whom all aspects of the person must be allowed to grow in the educative process” (Elias & Merriam, 2005, p. 124).

Merriam notes that education has historically gravitated to perpetuating the mainstream culture and societal norms. She also believes there is an assumption that knowledge is a commodity that is passed on from generation to generation and that “society’s elders know what knowledge and skills are necessary for maintaining the cultural status quo” (p. 123).

While educators have made great strides to empower students with a more humanistic style of teaching, including learner-centered teaching and experiential learning, ERT became a retrograde force compelling many teachers to instinctively fall back to a position of “taking back control” of the classroom through lecture-based, albeit virtual, instruction.

During our normal course development process in distance learning, we spend a great deal of time with faculty not only talking about the importance of asynchronous discussion boards but actually modeling their use during six weeks of online workshops with each faculty developer. The lack of time spent demonstrating the advantages of asynchronous discussions often leads to ERT faculty omitting their use entirely.

Online discussion boards are foundational to successful online learning communities. They embody many adult learning constructs, some of which include:

- Critically reflective writing

- Community-constructed knowledge

- Exposing learners to different worldviews

- Giving voice to all

Giving students time to think about answers to questions raised in class is a distinct advantage that asynchronous learning environments have to offer. And yet, this clear advantage is often underutilized and sometimes entirely overlooked in ERT.

According to Doug Lederman (2020), ERT led to 80% of instructors in one survey resorting to synchronous video “consistent with overwhelming anecdotal reports that many professors, especially those inexperienced in incorporating technology into their teaching, responded to this transition largely by clinging to the familiar—delivering lectures or holding class discussions with students via webcams.”

One of the most difficult transitions teachers can make is going from lecturer to listener. Another theme passed down through generations of adult educators is the importance of listening to others and making sure that everyone has a voice. Eduard Lindeman (1926) developed the “circular response exercise” in the 1930s which was used by David Stewart (1987) and then passed on to Stephen Brookfield (2017) who describes it as a way to “democratize group participation, to promote conversational continuity, and to give people some experience of the effort required in respectful listening” (p. 124).

The circular response exercise essentially requires students (optimally 8 to 12) to form a circle. One student starts the discussion on a given theme, then each student speaks, one at a time, for two minutes, going around the circle paraphrasing the previous speaker’s comments, then adding their own contribution. While they do not have to agree with the previous speaker, they must incorporate the ideas of the previous speaker into their own contribution. They are not free to speak out of context nor is anyone else permitted to interrupt in any way. The conversation then opens up into a free discussion with no ground rules.

In asynchronous discussions, the problem of managing extroverts and introverts is largely solved by the medium itself. All that is needed is for instructors to take advantage of the medium and inject the theme and rules of engagement.[1] This, in itself, is a skill that online instructors need to nurture and develop. However, one can easily see the influence of the circular response exercise in the usual instructions provided to students in online synchronous discussions; post a substantial opening statement to the group, and then reply to at least two other students.

To emphasize the importance of asynchronous discussions, Flower Darby (2020) says, “As a veteran online teacher, I view discussion forums as the meat and potatoes of my online courses. They are where my teaching happens—where I interact with students, guide their learning, and get to know them as people. The joy I’ve come to find in online teaching stems directly from those interactions.”

Nimble Redesign of Critical Thinking Activities

In The Great Onlining of 2020, “Almost two-thirds [of instructors] said they changed ‘the kinds of assignments or exams’ they gave to students” and 46% “dropped some assignments or exams,” (Lederman, 2020).

In an emergency remote teaching context, in which faculty have a very short amount of time to develop and teach their course in a completely different modality, critical thinking is often the primary strategy abandoned. First, instructors, pressed for time, consider critical thinking activities too difficult to achieve in online learning; but also, and more fundamentally, instructors do not feel that time spent applying critical thinking skills to their individual course design contexts is worthwhile.

The first assumption, that critical thinking activities are not well-suited to online instruction, may be driven by experiences with computer-based training (CBT), predominantly self-paced instruction in the form of a slide-based interactive. If an instructor’s only prior experience with online learning is compliance training—voiceover slides followed by multiple-choice questions—it is difficult to imagine all of the possibilities that online learning affords.

The second assumption, that time spent thinking critically about creative activities and assessments is time wasted, may stem from either a lack of teaching experience (as in the case of graduate students who may be new to teaching) or from many years of teaching experience (as in the case of the long-term instructor who receives rave reviews as an engaging face-to-face lecturer).

From speaking with instructors on both ends of the spectrum in the university-wide practicum, it was clear that instructors both chose not to critically engage and also felt that they were not capable of critically engaging due to a lack of technology skills and/or time. As a result, they felt trapped in an online learning environment that they were not comfortable using and overwhelmed by the amount of time spent developing course materials that they felt were destined to be less effective, such as video lectures. In such a circumstance, there is simply no way to squeeze in time to develop OOL strategies. Understandably, they focused on direct translation of course materials as opposed to transformation.

A situation from Krissy’s class, a five-week asynchronous online professional writing course for undergraduate business students, provides one example of how an instructor could apply critical thinking to course design and structure to modify a critical thinking activity for the unique needs of a COVID-19 online teaching environment.

She began the course with an exercise about audience, in which students write three emails on the same topic to three different groups: a team of four peers, a team supervisor, and to the entire organization. It seemed pragmatic to choose remote work policies as the core content for the activity, as business students would likely encounter such a topic in their future workplaces. She composed three case studies:

- How would you email a group of four peers to learn more about their opinions of remote work and what policies they would prefer if you were to advocate for them?

- Assuming your peers would like to work remotely at least some of the time, how would you email a supervisor to share your peers’ opinions and request time to discuss?

- Assuming you met with your supervisor and they agreed to your plan, how would you inform everyone in the office of the changing work-from-home policy?

This assignment worked well in winter 2020, for the first section of the course in January and even for the second section of the course in early March. However, by the time the Spring term came around, it was clear that some changes needed to be made.

For spring, she gave students the choice between two slightly different scenarios. One assumed that the office had abruptly started working remotely due to COVID-19, and that work-from-home policies needed to be codified. The other looked to the future, asking students to imagine a return to the office after COVID-19, and requesting a work-from-home policy having proven that they had already worked remotely successfully.

Come August, as it became clearer that COVID-19 would affect our lives for longer than a few weeks or months, she tweaked the first scenario for the Fall class again. This time, the student role-plays an employee taking stock of hastily established work-from-home policies in order to problem-solve for needed changes. It was important to her to still provide the second option, allowing students to mentally fast-forward to a time when COVID-19 is no longer a concern.

This activity stands in stark contrast to typical outcome-driven ERT, in which critical thinking is considered too difficult to achieve. The focus is on converting content such as slides and lectures, and then delivering it to students, as if they are vessels to simply receive knowledge. Optimal online learning more broadly develops critical thinking activities and then considers what resources students will need to respond in an informed manner.

In this activity, students encounter a disorienting dilemma in order to achieve transformative learning through self-reflection and open sharing of unique perspectives (Mezirow, 2000). This activity does not ask students to memorize or recall, but rather to use resources to complete complex tasks and form complex arguments and opinions. It is the exact opposite of “teaching to the test,” in that every student will compose a different message; there is no correct response, but a range of effective and creative responses.

Early in the course, students take stock of their prior knowledge through self-assessment and goal-setting activities. Throughout the course, students revisit those goals, take stock in their progress, plan for forthcoming activities, and identify both strengths and opportunities for improvement. Toward the end of the course, students synthesize their experiences prior to and throughout the course to reflect both topically and metacognitively. What writing strategies did they develop, certainly, but how did their perspective change?

Of course, it is critical to cultivate an OOL environment where students feel comfortable sharing prior experiences, challenging each other, and encountering disorienting dilemmas while in a respectful, facilitated environment.

From Teaching to Students to Nurturing a Community of Learners

In over 15 years of working with faculty members, we cannot count how many times we have heard the phrase, “I learn so much from my students.” And yet, in ERT we have paid lip service to the concept of a community of learners. In our day-to-day teaching and especially in online learning communities, building a community of learners inclusive of the teacher is paramount to OOL.

Palloff and Pratt (2007) point out in their seminal work, Building Online Learning Communities, that

the principles involved in the delivery of distance education are basically those attributed to a more active, constructivist form of learning—with one difference: in distance education, attention needs to be paid to the developing sense of community within the group of participants in order for the learning process to be successful. The learning community is the vehicle through which learning occurs online. (p. 40)

In David’s class on learning environment design, he has students create a community charter in a shared, cloud-accessed document while working on their other readings and assignments during the first couple of weeks of class. With few instructions provided by him, it is as much a lesson in self-governance and democratic participation as it is an opportunity to get to know one another and negotiate working relationships, roles, and responsibilities. Students often reach out to tell him how difficult the activity is, but by the end of the class, many of those same students report it as being one of the most rewarding and enlightening experiences they have had in an online class.

Malcolm Knowles (1984) built his life’s work upon the European concept of andragogy to describe the art and science of helping adults learn. However, while his initial work saw pedagogy, the education of children, being different from that of andragogy, as he developed his theories he came to the regard “the pedagogical and andragogical models as parallel, not antithetical” (p.12).

Knowles once said that he regarded Eduard C. Lindeman as “the single most influential person in guiding my thinking,” (p. 3) and in turn, Knowles’ own andragogical system of concepts has now become a guiding force for a new generation of adult educators, learning designers, and those of us who advocate for OOL.

While Knowles originally summarized andragogy as being premised on four assumptions, he later expanded them to six. We have summarized them here:

- Self-Concept: Adults believe they are responsible for their lives and they want to be treated as capable and self-directed.

- Life Experiences: Adults come into an educational activity with different experiences than younger learners. These unique experiences should be respected and taken into account when designing learning activities.

- Readiness to Learn: Adults become ready to learn things they need to know and do in order to cope effectively with real-life situations.

- Practical: Adults are task-centered/problem-centered in their orientation to learning.

- Goal Oriented: Adults want to know why they need to learn something before undertaking to learn.

- Motivation: Adults are responsive to some external motivators (e.g., a better job, higher salaries), but the most potent motivators are internal (e.g., desire for increased job satisfaction, self-esteem).

With the massive transition to online learning, the parallel paths of pedagogy and andragogy have moved closer together. OOL requires an active and constructivist approach to learning as Palloff and Pratt (2007) stated. Some of Knowles’ assumptions can and should be applied not only to adults learning online but to adolescents as well.

Mike Klein (2019) uses an activity with his master’s- and doctoral-level students called “I am from . . . .” He frames the activity as an exercise in self-knowledge, intersectional identities, and critical pedagogy. Klein states that “as practitioner-scholars, self-knowledge is essential in order to problematize and evaluate identity construction, and to understand biases, prejudices, and racialized assumptions” (p. 89).

He describes the “I am from” activity as a face-to-face discussion that takes place as follows:

- A 2- to 3-minute introduction in which the instructor passes around a worksheet with the phrase, “I am from . . . ” at the top of the page. Klein suggests the instructor model the activity to “set expectations for the quality of the responses” (p. 92)

- 10–12 minutes for students’ written responses

- 15 minutes for students to read their responses out loud

While Klein’s full worksheet of “I am from . . . ” responses is too extensive to list here, he includes responses such as:

- I am from (geography)

- I am from (gender)

- I am from (class)

- I am from (ethnicity/race/nationality)

. . . and many more.

Klein provides an example of the type of answer he is expecting with his own answer to what class he hails from.

I am from . . . a lower-middle-class family who made me feel rich without having material wealth, substantial income, or financial resources (p. 92).

Lott Hill, Soo La Kim, and Megan Stielstra (2016) used to kick off all-day faculty workshops at the Center for Innovation in Teaching Excellence at Columbia College in Chicago with a similar activity called the “mapping exercise.” The questions were similar, but the participants were asked to move around in space as if positioning themselves on a map to describe where they were from, then where their families were from, and lastly, where they themselves called home.

Such simple activities inspired by the critical pedagogy of adult educators like Paulo Freire (1976), and bell hooks (1994) can have a profound impact on OOL if only adapted to a fully online environment.

Here is our own adaptation of Mark Klein’s “I am from . . . ” activity to an online class:

- Create a 2- to 3-minute video where the instructor introduces the activity, provides instructions and gives an example of how they would answer one or more of the questions.

- Create an asynchronous discussion board and allow students to post their answers to five possible “I am from . . . ” queries by mid-week (allowing them time to critically reflect on their identities and self-knowledge).

- Ask students to respond to two other students’ answers with follow-up questions in written, audio, or video format.

More than just a virtual icebreaker, the “I am from . . . ” online activity demonstrates how adult education activities designed for face-to-face environments can be effectively leveraged for a wider audience using asynchronous discussion boards and multimedia.

OOL Encapsulates Adult Education Strategies to Deliver Effective Online Learning

Coming Full Circle

dance round in a ring and suppose,

But the Secret sits in the middle and knows.

Robert Frost

The Great Onlining of 2020 has been the disorienting dilemma that has awakened our curiosity and made us question, once again, what it means to interact, teach, and learn in virtual communities. Academia seemed content to exist with boundaries between online learning advocates and skeptics. The urgency and inevitability of online learning as a result of COVID-19 has brought the two sides together, albeit reluctantly. But inevitably, we tend to pick up where we left off with our old assumptions.

As if to accentuate how disorienting this dilemma is, it seems we cannot even agree on the shape of our virtual classrooms. In Schaberg’s first opinion piece (2018), before his experience teaching online, he felt that,

We can’t sit in a circle online. I recognize that not everyone configures the classroom in a circle. Some instructors even think that rows are the natural, default shape of education. Anyway, I usually like to have my classes arranged in circles, ovals or weird amoebas so the students can see one another and so that my authority is less automatically pronounced. (p. 1)

Stephen Brookfield (2017) also feels the circle represents a more desirable learning space:

If it was at all possible I would get to class early to move the chairs out of their arrangement in neat rows and put them into a circle. . . . Why would I spend so much time on pedagogic feng shui? Well to my way of thinking the circle is a physical manifestation of democracy, a group of peers facing each other as respectful equals (pp. 77–78).

To this end, David usually starts his regular weekly web-conference sessions by asking students to “go around the room for a quick check-in” before starting his regular session. We often refer to learner-centered teaching as if that’s where learners are supposed to be!

The shape of our virtual classrooms is anything we want it to be. It’s an abstract concept that we need to nurture, and the technology will follow. Although learning-management systems provide linear, chronological ways to organize course content and activities, following a modular structure, and videoconferencing podiums or desks to pontificate behind, instructors can cultivate democratic, circular activities in OOL: bouncing ideas back and forth in discussions, looping back with reflection, revisiting critical thinking activities, patterning feedback and revision, and always returning to the learner at the center.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have described the difference between optimal online learning (OOL) and emergency remote teaching (ERT). While we do not criticize the need for ERT during The Great Onlining of 2020 caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, we also do not find the lack of preparedness among academic institutions reassuring. Academic scholars and researchers, including adult educators, epistemologists, learning designers, and pedagogical researchers have long understood and advocated for many of the ideas we have put forth here.

However, adult theorists have often taken the lead in applying many of these key elements to their face-to-face teaching. We believe that these same key elements can also be leveraged for the new reality of immediate and urgent well-designed online learning environments. We described the key elements of OOL as including:

- Learner-centered teaching

- Community building

- Experiential learning opportunities

- Opportunities for critical thinking

- Meaningful self-reflection

- Transformative learning

In addition to summarizing in Table 1 how OOL addresses these key elements and how ERT addresses them unsatisfactorily or often omits them entirely, we described in detail some examples of how specific adult learning theory can be applied to online learning environments.

Throughout our examples, we showed how online learning activities often use technology for specific pedagogical or andragogical purposes. Technology is not used to entertain or merely maintain interest in an online course, but rather to elicit specific behavioral, cognitive, constructivist, or connectivist learning. In some cases, our examples have been used in online environments, and in other cases, as in the “I am from . . . ” activity, they are yet to be adapted.

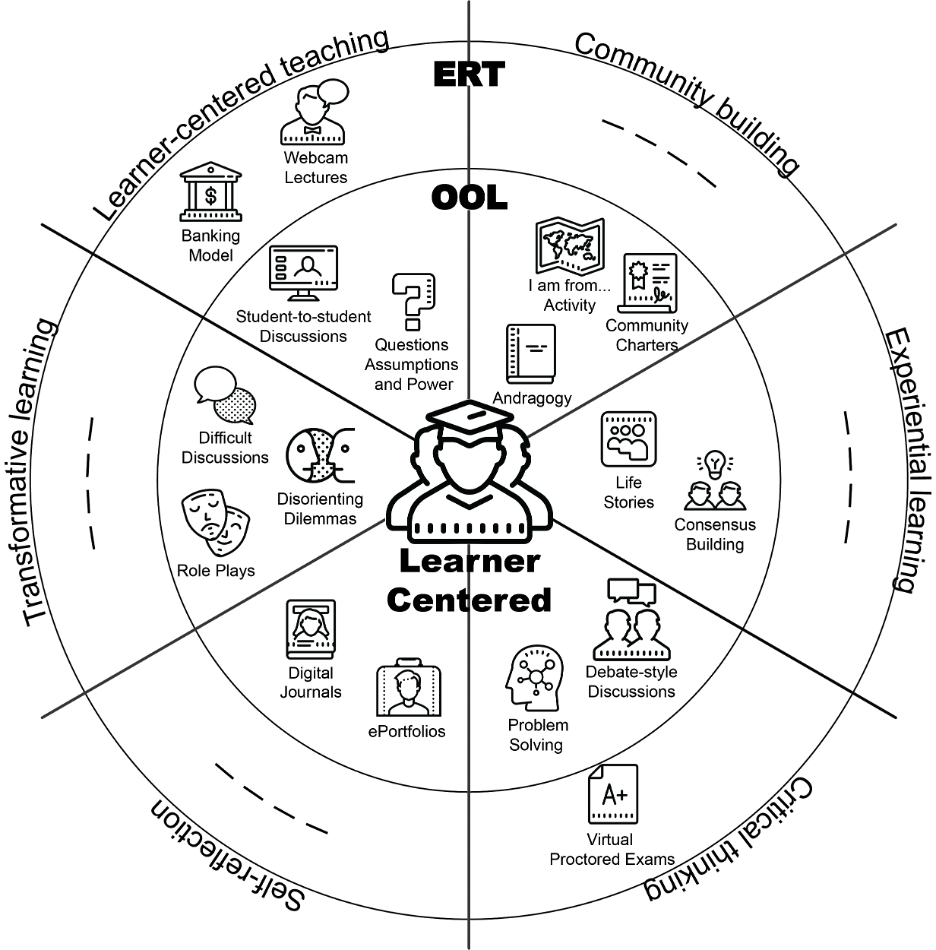

Lastly, in Figure 1, we show the relationship between learner and teacher/facilitator and how OOL encapsulates the key elements we have discussed in the chapter. This leads us to our closing argument that we need to see the traditional confines of classrooms as being liberated by the abstract shapes and relationships that can be found and sometimes forged in the new terrain of OOL.

We hope you will be the first to try it, for optimal online learning has the potential to impact the very learners most in need of engagement, such as first-generation students and students of color. Using OOL strategies may lead to increased persistence and degree completion by inviting personal connections with peers, faculty, and other members of the academic community such as advisors and librarians. Students who are successful in OOL may feel more affinity for their college or university and better advocate for their needs in other courses. For any student asking “Why? Why are we learning this?” “Why are we learning this now?” “Why is this structured this way?”—OOL provides the answers.

While not a panacea for the daunting challenges that face online education in current and postpandemic academia, OOL leverages the formidable work of adult educators across generations. At this critical juncture, it is more important than ever to listen to our peers from another place and time who, also daunted by challenges, nevertheless found ways to reach learners made distant through culture, race, or poverty.

References

Brookfield, S. (2017). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Cercone, K. (2008). Characteristics of adult learners with implications for online learning design. AACE, 16(2), 137–159.

Christensen, U. J. (2020, July 27). The real reason why the pandemic e-learning experiments didn’t work. Forbes. Retrieved January 18, 2021, from https://tinyurl.com/yy4xeb42

Darby, F. (2020, August 24). The secret weapon of good online teaching: Discussion forums. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved October 6, 2020, from https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-secret-weapon-of-good-online-teaching-discussion-forums

Dirkx, J. M., & Smith, R. O. (2009). Facilitating transformative learning: Engaging emotions in an online context. In J. Mezirow & E. W. Taylor (Eds.), Transformative Learning in Practice: Insights from Community, Workplace, and Higher Education (pp. 57–66). Jossey-Bass.

Dougiamas, M., & Taylor, P. (2003). Moodle: Using learning communities to create an open-source course management system. Dougiamas. Retrieved January 4, 2020, from https://dougiamas.com/archives/edmedia2003/

Elias, J. L., & Merriam, S. (2005). Philosophical foundations of adult education. (3rd ed.). Krieger.

Fischer, L. (2015). Let’s give ‘em something to talk about: Five instructor practices that cultivate online discussions.Northwestern School of Professional Studies. Retrieved January 18, 2021, from https://dl.sps.northwestern.edu/uncategorized/2015/05/something-to-talk-about/

Freire, P. (1976). Education as the practice of freedom. Writers and Readers Cooperative.

Freire, P. (2010). Pedagogy of the oppressed. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action. Vol. 1: Reason and the Rationalization of Society. (T. McCarthy, Trans.). Beacon Press. (Original work published 1981).

Hill, L., Kim, S. L., & Stielstra, M. (2016, May 19). Mapping exercise [Workshop facilitation]. Faculty Fellows Retreat, Chicago, IL.

Hitchcock, D. (2020). Critical thinking. In Zalta, E. N. (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/critical-thinking/

Hobbs, T. D., & Hawkins, L. (2020). The results are in for remote learning: It didn’t work. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 8, 2021, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/schools-coronavirus-remote-learning-lockdown-tech-11591375078

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review. https://tinyurl.com/ybnwz255

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Klein, M. (2019). Teaching intersectionality through “I am from . . .”. In S. Brookfield (Ed.), Teaching race. How to help students unmask and challenge racism (pp. 87–108). Jossey-Bass.

Knowles, M. S. (1984). Andragogy in action. Jossey-Bass.

Lederman, D. (2020). How teaching changed in the (forced) shift to remote learning. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved June 5, 2020, from https://insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2020/04/22/how-professors-changed-their-teaching-springs-shift-remote

Lindeman, E. C. (1926). The meaning of adult education. Harvest House.

Mezirow, J. (1978). Perspective transformation. Adult Education Quarterly. 28(2), 100–110.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass Inc.

Mezirow, J., & Taylor, E. W. (2009). Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education. Jossey-Bass.

Palloff, R. M. & Pratt, K. (2007). Building online learning communities: Effective strategies for the virtual classroom. Jossey-Bass.

Ralph, N. (2020). Perspectives: Covid-19, and the future of higher education. Bay View Analytics. https://onlinelearningsurvey.com/covid.html

Schaberg, C. (2018). Why I won’t teach online. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved October 21, 2020, from https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/views/2018/03/07/professor-explains-why-he-wont-teach-online-opinion

Schaberg, C. (2020). Why I’m teaching online. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved October 21, 2020, from https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/09/11/professor-who-asserted-hed-never-teach-online-explains-why-hes-opting-do-so-now

Siemens, G. [@gsiemens]. (2020, March 11) What are the best research-informed articles you’re using to guide The Great Onlining of 2020? I see many practitioner opinion pieces. Less research-based contributions [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/gsiemens/status/1237868781835186177

Singman, B. (2020). Trump says “virtual learning has proven to be terrible,” threatens cuts to federal funds. Fox News. Retrieved January 18, 2021, from https://www.foxnews.com/politics/trump-says-virtual-learning-has-proven-to-be-terrible-threatens-cuts-to-federal-funds

Stewart, D. (1987). Adult learning in america: Eduard Lindeman and his agenda for lifelong education. Krieger.

Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-centered teaching. Jossey-Bass.

- While a full discussion on the impact of effective asynchronous discussions is not possible here, the reader can find numerous articles on the topic, including this blog post by one of our own colleagues, School of Professional Studies lecturer Leslie Fischer, “Five Instructor Practices that Cultivate Online Discussions” (2015). ↵