Thinking like a Scientist

Erin I. Smith

We are bombarded every day with claims about how the world works, claims that have a direct impact on how we think about and solve problems in society and our personal lives. This module explores important considerations for evaluating the trustworthiness of such claims by contrasting between scientific thinking and everyday observations (also known as “anecdotal evidence”).

Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast conclusions based on scientific and everyday inductive reasoning.

- Understand why scientific conclusions and theories are trustworthy, even if they are not able to be proven.

- Articulate what it means to think like a psychological scientist, considering qualities of good scientific explanations and theories.

- Discuss science as a social activity, comparing and contrasting facts and values.

Introduction

Why are some people so much happier than others? Is it harmful for children to have imaginary companions? How might students study more effectively?

Even if you’ve never considered these questions before, you probably have some guesses about their answers. Maybe you think getting rich or falling in love leads to happiness. Perhaps you view imaginary friends as expressions of a dangerous lack of realism. What’s more, if you were to ask your friends, they would probably also have opinions about these questions—opinions that may even differ from your own.

A quick internet search would yield even more answers. We live in the “Information Age,” with people having access to more explanations and answers than at any other time in history. But, although the quantity of information is continually increasing, it’s always good practice to consider the quality of what you read or watch: Not all information is equally trustworthy. The trustworthiness of information is especially important in an era when “fake news,” urban myths, misleading “click-bait,” and conspiracy theories compete for our attention alongside well-informed conclusions grounded in evidence. Determining what information is well-informed is a crucial concern and a central task of science. Science is a way of using observable data to help explain and understand the world around us in a trustworthy way.

In this module, you will learn about scientific thinking. You will come to understand how scientific research informs our knowledge and helps us create theories. You will also come to appreciate how scientific reasoning is different from the types of reasoning people often use to form personal opinions.

Scientific Versus Everyday Reasoning

Each day, people offer statements as if they are facts, such as, “It looks like rain today,” or, “Dogs are very loyal.” These conclusions represent hypotheses about the world: best guesses as to how the world works. Scientists also draw conclusions, claiming things like, “There is an 80% chance of rain today,” or, “Dogs tend to protect their human companions.” You’ll notice that the two examples of scientific claims use less certain language and are more likely to be associated with probabilities. Understanding the similarities and differences between scientific and everyday (non-scientific) statements is essential to our ability to accurately evaluate the trustworthiness of various claims.

Scientific and everyday reasoning both employ induction: drawing general conclusions from specific observations. For example, a person’s opinion that cramming for a test increases performance may be based on her memory of passing an exam after pulling an all-night study session. Similarly, a researcher’s conclusion against cramming might be based on studies comparing the test performances of people who studied the material in different ways (e.g., cramming versus study sessions spaced out over time). In these scenarios, both scientific and everyday conclusions are drawn from a limited sample of potential observations.

The process of induction, alone, does not seem suitable enough to provide trustworthy information—given the contradictory results. What should a student who wants to perform well on exams do? One source of information encourages her to cram, while another suggests that spacing out her studying time is the best strategy. To make the best decision with the information at hand, we need to appreciate the differences between personal opinions and scientific statements, which requires an understanding of science and the nature of scientific reasoning.

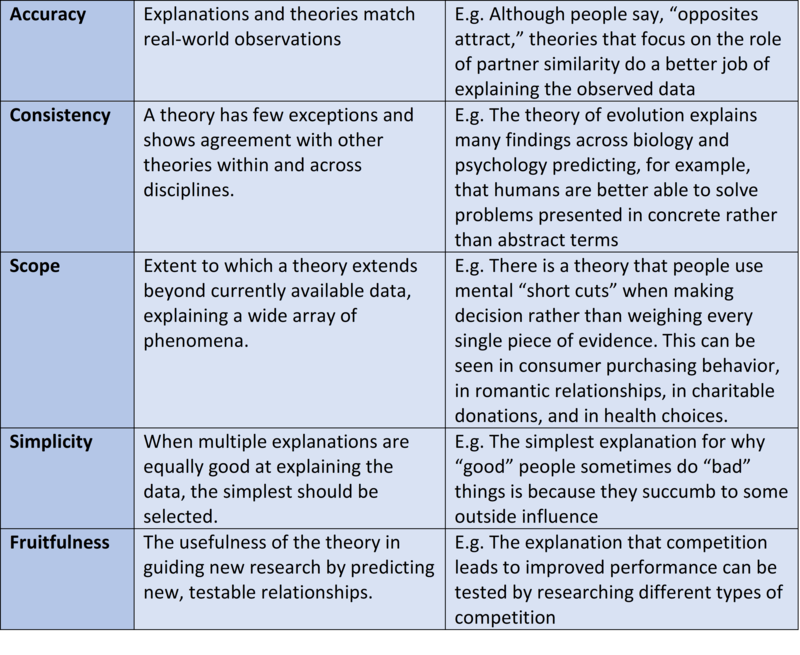

There are generally agreed-upon features that distinguish scientific thinking—and the theories and data generated by it—from everyday thinking. A short list of some of the commonly cited features of scientific theories and data is shown in Table 1.

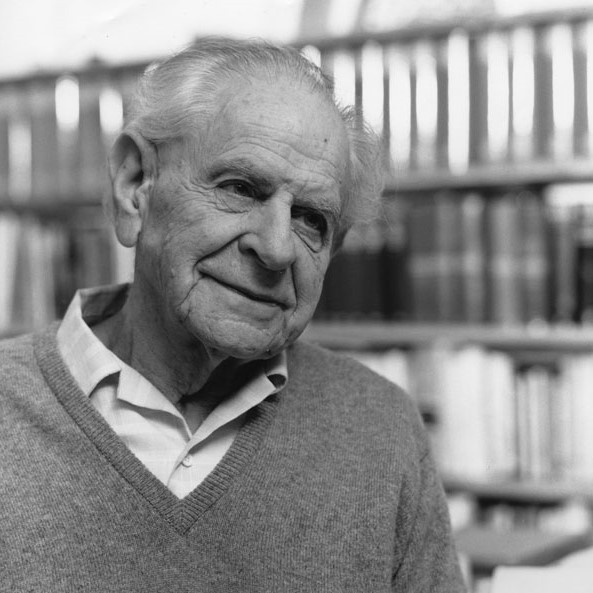

One additional feature of modern science not included in this list but prevalent in scientists’ thinking and theorizing is falsifiability, a feature that has so permeated scientific practice that it warrants additional clarification. In the early 20th century, Karl Popper (1902-1994) suggested that science can be distinguished from pseudoscience (or just everyday reasoning) because scientific claims are capable of being falsified. That is, a claim can be conceivably demonstrated to be untrue. For example, a person might claim that “all people are right handed.” This claim can be tested and—ultimately—thrown out because it can be shown to be false: There are people who are left-handed. An easy rule of thumb is to not get confused by the term “falsifiable” but to understand that—more or less—it means testable.

On the other hand, some claims cannot be tested and falsified. Imagine, for instance, that a magician claims that he can teach people to move objects with their minds. The trick, he explains, is to truly believe in one’s ability for it to work. When his students fail to budge chairs with their minds, the magician scolds, “Obviously, you don’t truly believe.” The magician’s claim does not qualify as falsifiable because there is no way to disprove it. It is unscientific.

Popper was particularly irritated about nonscientific claims because he believed they were a threat to the science of psychology. Specifically, he was dissatisfied with Freud’s explanations for mental illness. Freud believed that when a person suffers a mental illness it is often due to problems stemming from childhood. For instance, imagine a person who grows up to be an obsessive perfectionist. If she were raised by messy, relaxed parents, Freud might argue that her adult perfectionism is a reaction to her early family experiences—an effort to maintain order and routine instead of chaos. Alternatively, imagine the same person being raised by harsh, orderly parents. In this case, Freud might argue that her adult tidiness is simply her internalizing her parents’ way of being. As you can see, according to Freud’s rationale, both opposing scenarios are possible; no matter what the disorder, Freud’s theory could explain its childhood origin—thus failing to meet the principle of falsifiability.

Popper argued against statements that could not be falsified. He claimed that they blocked scientific progress: There was no way to advance, refine, or refute knowledge based on such claims. Popper’s solution was a powerful one: If science showed all the possibilities that were not true, we would be left only with what is true. That is, we need to be able to articulate—beforehand—the kinds of evidence that will disprove our hypothesis and cause us to abandon it.

This may seem counterintuitive. For example, if a scientist wanted to establish a comprehensive understanding of why car accidents happen, she would systematically test all potential causes: alcohol consumption, speeding, using a cell phone, fiddling with the radio, wearing sandals, eating, chatting with a passenger, etc. A complete understanding could only be achieved once all possible explanations were explored and either falsified or not. After all the testing was concluded, the evidence would be evaluated against the criteria for falsification, and only the real causes of accidents would remain. The scientist could dismiss certain claims (e.g., sandals lead to car accidents) and keep only those supported by research (e.g., using a mobile phone while driving increases risk). It might seem absurd that a scientist would need to investigate so many alternative explanations, but it is exactly how we rule out bad claims. Of course, many explanations are complicated and involve multiple causes—as with car accidents, as well as psychological phenomena.

Test Yourself 1: Can it be falsified?

Although the idea of falsification remains central to scientific data and theory development, these days it’s not used strictly the way Popper originally envisioned it. To begin with, scientists aren’t solely interested in demonstrating what isn’t. Scientists are also interested in providing descriptions and explanations for the way things are. We want to describe different causes and the various conditions under which they occur. We want to discover when young children start speaking in complete sentences, for example, or whether people are happier on the weekend, or how exercise impacts depression. These explorations require us to draw conclusions from limited samples of data. In some cases, these data seem to fit with our hypotheses and in others they do not. This is where interpretation and probability come in.

The Interpretation of Research Results

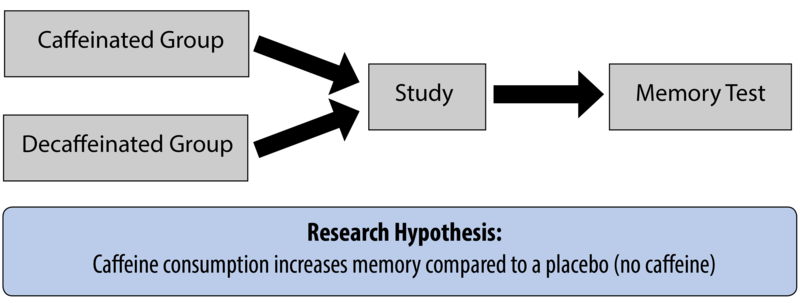

Imagine a researcher wanting to examine the hypothesis—a specific prediction based on previous research or scientific theory—that caffeine enhances memory. She knows there are several published studies that suggest this might be the case, and she wants to further explore the possibility. She designs an experiment to test this hypothesis. She randomly assigns some participants a cup of fully caffeinated tea and some a cup of herbal tea. All the participants are instructed to drink up, study a list of words, then complete a memory test. There are three possible outcomes of this proposed study:

- The caffeine group performs better (support for the hypothesis).

- The no-caffeine group performs better (evidence against the hypothesis).

- There is no difference in the performance between the two groups (also evidence against the hypothesis).

Let’s look, from a scientific point of view, at how the researcher should interpret each of these three possibilities.

First, if the results of the memory test reveal that the caffeine group performs better, this is a piece of evidence in favor of the hypothesis: It appears, at least in this case, that caffeine is associated with better memory. It does not, however, prove that caffeine is associated with better memory. There are still many questions left unanswered. How long does the memory boost last? Does caffeine work the same way with people of all ages? Is there a difference in memory performance between people who drink caffeine regularly and those who never drink it? Could the results be a freak occurrence? Because of these uncertainties, we do not say that a study—especially a single study—proves a hypothesis. Instead, we say the results of the study offer evidence in support of the hypothesis. Even if we tested this across 10 thousand or 100 thousand people we still could not use the word “proven” to describe this phenomenon. This is because inductive reasoning is based on probabilities. Probabilities are always a matter of degree; they may be extremely likely or unlikely. Science is better at shedding light on the likelihood—or probability—of something than at proving it. In this way, data is still highly useful even if it doesn’t fit Popper’s absolute standards.

The science of meteorology helps illustrate this point. You might look at your local weather forecast and see a high likelihood of rain. This is because the meteorologist has used inductive reasoning to create her forecast. She has taken current observations—lots of dense clouds coming toward your city—and compared them to historical weather patterns associated with rain, making a reasonable prediction of a high probability of rain. The meteorologist has not proven it will rain, however, by pointing out the oncoming clouds.

Proof is more associated with deductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning starts with general principles that are applied to specific instances (the reverse of inductive reasoning). When the general principles, or premises, are true, and the structure of the argument is valid, the conclusion is, by definition, proven; it must be so. A deductive truth must apply in all relevant circumstances. For example, all living cells contain DNA. From this, you can reason—deductively—that any specific living cell (of an elephant, or a person, or a snake) will therefore contain DNA. Given the complexity of psychological phenomena, which involve many contributing factors, it is nearly impossible to make these types of broad statements with certainty.

Test Yourself 2: Inductive or Deductive?

The second possible result from the caffeine-memory study is that the group who had no caffeine demonstrates better memory. This result is the opposite of what the researcher expects to find (her hypothesis). Here, the researcher must admit the evidence does not support her hypothesis. She must be careful, however, not to extend that interpretation to other claims. For example, finding increased memory in the no-caffeine group would not be evidence that caffeine harms memory. Again, there are too many unknowns. Is this finding a freak occurrence, perhaps based on an unusual sample? Is there a problem with the design of the study? The researcher doesn’t know. She simply knows that she was not able to observe support for her hypothesis.

There is at least one additional consideration: The researcher originally developed her caffeine-benefits-memory hypothesis based on conclusions drawn from previous research. That is, previous studies found results that suggested caffeine boosts memory. The researcher’s single study should not outweigh the conclusions of many studies. Perhaps the earlier research employed participants of different ages or who had different baseline levels of caffeine intake. This new study simply becomes a piece of fabric in the overall quilt of studies of the caffeine-memory relationship. It does not, on its own, definitively falsify the hypothesis.

Finally, it’s possible that the results show no difference in memory between the two groups. How should the researcher interpret this? How would you? In this case, the researcher once again has to admit that she has not found support for her hypothesis.

Interpreting the results of a study—regardless of outcome—rests on the quality of the observations from which those results are drawn. If you learn, say, that each group in a study included only four participants, or that they were all over 90 years old, you might have concerns. Specifically, you should be concerned that the observations, even if accurate, aren’t representative of the general population. This is one of the defining differences between conclusions drawn from personal anecdotes and those drawn from scientific observations. Anecdotal evidence—derived from personal experience and unsystematic observations (e.g., “common sense,”)—is limited by the quality and representativeness of observations, and by memory shortcomings. Well-designed research, on the other hand, relies on observations that are systematically recorded, of high quality, and representative of the population it claims to describe.

Why Should I Trust Science If It Can’t Prove Anything?

It’s worth delving a bit deeper into why we ought to trust the scientific inductive process, even when it relies on limited samples that don’t offer absolute “proof.” To do this, let’s examine a widespread practice in psychological science: null-hypothesis significance testing.

To understand this concept, let’s begin with another research example. Imagine, for instance, a researcher is curious about the ways maturity affects academic performance. She might have a hypothesis that mature students are more likely to be responsible about studying and completing homework and, therefore, will do better in their courses. To test this hypothesis, the researcher needs a measure of maturity and a measure of course performance. She might calculate the correlation—or relationship—between student age (her measure of maturity) and points earned in a course (her measure of academic performance). Ultimately, the researcher is interested in the likelihood—or probability—that these two variables closely relate to one another. Null-hypothesis significance testing (NHST) assesses the probability that the collected data (the observations) would be the same if there were no relationship between the variables in the study. Using our example, the NHST would test the probability that the researcher would find a link between age and class performance if there were, in reality, no such link.

Now, here’s where it gets a little complicated. NHST involves a null hypothesis, a statement that two variables are not related (in this case, that student maturity and academic performance are not related in any meaningful way). NHST also involves an alternative hypothesis, a statement that two variables are related (in this case, that student maturity and academic performance go together). To evaluate these two hypotheses, the researcher collects data. The researcher then compares what she expects to find (probability) with what she actually finds (the collected data) to determine whether she can falsify, or reject, the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis.

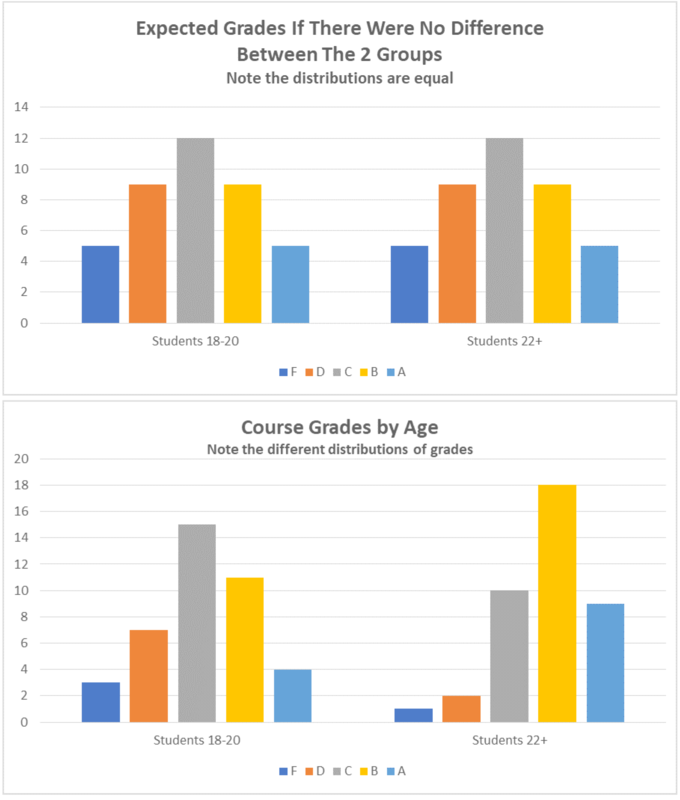

How does she do this? By looking at the distribution of the data. The distribution is the spread of values—in our example, the numeric values of students’ scores in the course. The researcher will test her hypothesis by comparing the observed distribution of grades earned by older students to those earned by younger students, recognizing that some distributions are more or less likely. Your intuition tells you, for example, that the chances of every single person in the course getting a perfect score are lower than their scores being distributed across all levels of performance.

The researcher can use a probability table to assess the likelihood of any distribution she finds in her class. These tables reflect the work, over the past 200 years, of mathematicians and scientists from a variety of fields. You can see, in Table 2a, an example of an expected distribution if the grades were normally distributed (most are average, and relatively few are amazing or terrible). In Table 2b, you can see possible results of this imaginary study, and can clearly see how they differ from the expected distribution.

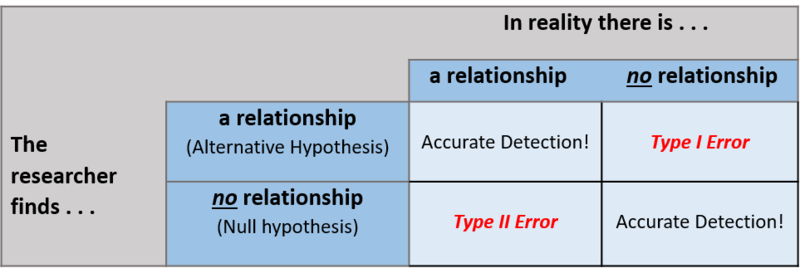

In the process of testing these hypotheses, there are four possible outcomes. These are determined by two factors: 1) reality, and 2) what the researcher finds (see Table 3). The best possible outcome is accurate detection. This means that the researcher’s conclusion mirrors reality. In our example, let’s pretend the more mature students do perform slightly better. If this is what the researcher finds in her data, her analysis qualifies as an accurate detection of reality. Another form of accurate detection is when a researcher finds no evidence for a phenomenon, but that phenomenon doesn’t actually exist anyway! Using this same example, let’s now pretend that maturity has nothing to do with academic performance. Perhaps academic performance is instead related to intelligence or study habits. If the researcher finds no evidence for a link between maturity and grades and none actually exists, she will have also achieved accurate detection.

There are a couple of ways that research conclusions might be wrong. One is referred to as a type I error—when the researcher concludes there is a relationship between two variables but, in reality, there is not. Back to our example: Let’s now pretend there’s no relationship between maturity and grades, but the researcher still finds one. Why does this happen? It may be that her sample, by chance, includes older students who also have better study habits and perform better: The researcher has “found” a relationship (the data appearing to show age as significantly correlated with academic performance), but the truth is that the apparent relationship is purely coincidental—the result of these specific older students in this particular sample having better-than-average study habits (the real cause of the relationship). They may have always had superior study habits, even when they were young.

Another possible outcome of NHST is a type II error, when the data fail to show a relationship between variables that actually exists. In our example, this time pretend that maturity is —in reality—associated with academic performance, but the researcher doesn’t find it in her sample. Perhaps it was just her bad luck that her older students are just having an off day, suffering from test anxiety, or were uncharacteristically careless with their homework: The peculiarities of her particular sample, by chance, prevent the researcher from identifying the real relationship between maturity and academic performance.

These types of errors might worry you, that there is just no way to tell if data are any good or not. Researchers share your concerns, and address them by using probability values (p-values) to set a threshold for type I or type II errors. When researchers write that a particular finding is “significant at a p < .05 level,” they’re saying that if the same study were repeated 100 times, we should expect this result to occur—by chance—fewer than five times. That is, in this case, a Type I error is unlikely. Scholars sometimes argue over the exact threshold that should be used for probability. The most common in psychological science are .05 (5% chance), .01 (1% chance), and .001 (1/10th of 1% chance). Remember, psychological science doesn’t rely on definitive proof; it’s about the probability of seeing a specific result. This is also why it’s so important that scientific findings be replicated in additional studies.

It’s because of such methodologies that science is generally trustworthy. Not all claims and explanations are equal; some conclusions are better bets, so to speak. Scientific claims are more likely to be correct and predict real outcomes than “common sense” opinions and personal anecdotes. This is because researchers consider how to best prepare and measure their subjects, systematically collect data from large and—ideally—representative samples, and test their findings against probability.

Scientific Theories

The knowledge generated from research is organized according to scientific theories. A scientific theory is a comprehensive framework for making sense of evidence regarding a particular phenomenon. When scientists talk about a theory, they mean something different from how the term is used in everyday conversation. In common usage, a theory is an educated guess—as in, “I have a theory about which team will make the playoffs,” or, “I have a theory about why my sister is always running late for appointments.” Both of these beliefs are liable to be heavily influenced by many untrustworthy factors, such as personal opinions and memory biases. A scientific theory, however, enjoys support from many research studies, collectively providing evidence, including, but not limited to, that which has falsified competing explanations. A key component of good theories is that they describe, explain, and predict in a way that can be empirically tested and potentially falsified.

Theories are open to revision if new evidence comes to light that compels reexamination of the accumulated, relevant data. In ancient times, for instance, people thought the Sun traveled around the Earth. This seemed to make sense and fit with many observations. In the 16th century, however, astronomers began systematically charting visible objects in the sky, and, over a 50-year period, with repeated testing, critique, and refinement, they provided evidence for a revised theory: The Earth and other cosmic objects revolve around the Sun. In science, we believe what the best and most data tell us. If better data come along, we must be willing to change our views in accordance with the new evidence.

Is Science Objective?

Thomas Kuhn (2012), a historian of science, argued that science, as an activity conducted by humans, is a social activity. As such, it is—according to Kuhn—subject to the same psychological influences of all human activities. Specifically, Kuhn suggested that there is no such thing as objective theory or data; all of science is informed by values. Scientists cannot help but let personal/cultural values, experiences, and opinions influence the types of questions they ask and how they make sense of what they find in their research. Kuhn’s argument highlights a distinction between facts (information about the world), and values (beliefs about the way the world is or ought to be). This distinction is an important one, even if it is not always clear.

To illustrate the relationship between facts and values, consider the problem of global warming. A vast accumulation of evidence (facts) substantiates the adverse impact that human activity has on the levels of greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere leading to changing weather patterns. There is also a set of beliefs (values), shared by many people, that influences their choices and behaviors in an attempt to address that impact (e.g., purchasing electric vehicles, recycling, bicycle commuting). Our values—in this case, that Earth as we know it is in danger and should be protected—influence how we engage with facts. People (including scientists) who strongly endorse this value, for example, might be more attentive to research on renewable energy.

The primary point of this illustration is that (contrary to the image of scientists as outside observers to the facts, gathering them neutrally and without bias from the natural world) all science—especially social sciences like psychology—involves values and interpretation. As a result, science functions best when people with diverse values and backgrounds work collectively to understand complex natural phenomena.

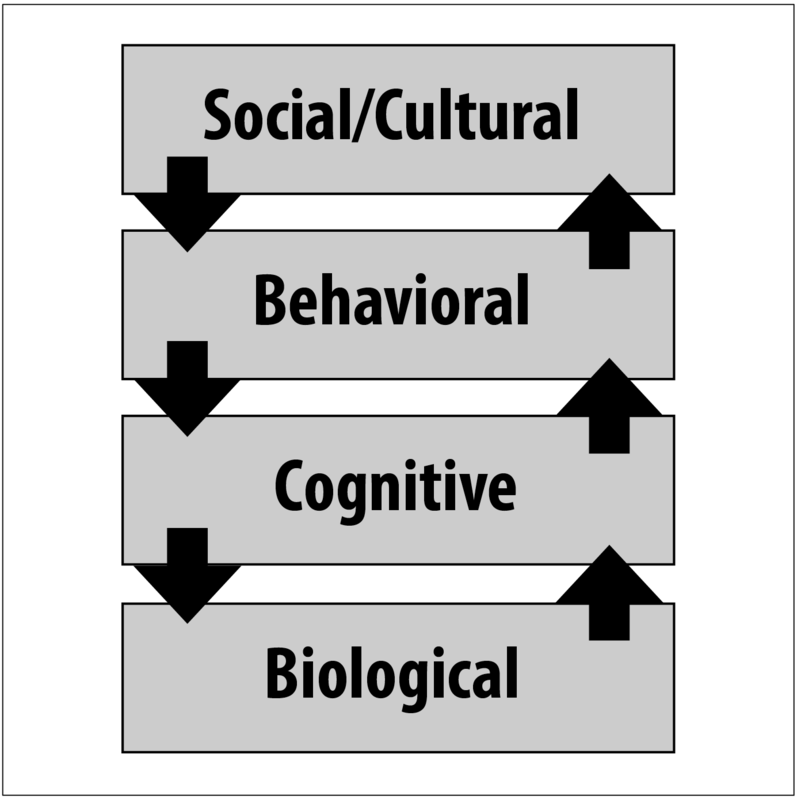

Indeed, science can benefit from multiple perspectives. One approach to achieving this is through levels of analysis. Levels of analysis is the idea that a single phenomenon may be explained at different levels simultaneously. Remember the question concerning cramming for a test versus studying over time? It can be answered at a number of different levels of analysis. At a low level, we might use brain scanning technologies to investigate whether biochemical processes differ between the two study strategies. At a higher level—the level of thinking—we might investigate processes of decision making (what to study) and ability to focus, as they relate to cramming versus spaced practice. At even higher levels, we might be interested in real world behaviors, such as how long people study using each of the strategies. Similarly, we might be interested in how the presence of others influences learning across these two strategies. Levels of analysis suggests that one level is not more correct—or truer—than another; their appropriateness depends on the specifics of the question asked. Ultimately, levels of analysis would suggest that we cannot understand the world around us, including human psychology, by reducing the phenomenon to only the biochemistry of genes and dynamics of neural networks. But, neither can we understand humanity without considering the functions of the human nervous system.

Science in Context

There are many ways to interpret the world around us. People rely on common sense, personal experience, and faith, in combination and to varying degrees. All of these offer legitimate benefits to navigating one’s culture, and each offers a unique perspective, with specific uses and limitations. Science provides another important way of understanding the world and, while it has many crucial advantages, as with all methods of interpretation, it also has limitations. Understanding the limits of science—including its subjectivity and uncertainty—does not render it useless. Because it is systematic, using testable, reliable data, it can allow us to determine causality and can help us generalize our conclusions. By understanding how scientific conclusions are reached, we are better equipped to use science as a tool of knowledge.

Discussion Questions

- When you think of a “scientist,” what image comes to mind? How is this similar to or different from the image of a scientist described in this module?

- What makes the inductive reasoning used in the scientific process different than the inductive reasoning we employ in our daily lives? How do these differences influence our trust in the conclusions?

- Why aren’t horoscopes considered scientific?

- If science cannot “prove” something, why do you think so many media reports of scientific research use this word? As an educated consumer of research, what kinds of questions should you ask when reading these secondary reports?

- In thinking about the application of research in our lives, which is more meaningful: individual research studies and their conclusions or scientific theories? Why?

- Although many people believe the conclusions offered by science generally, there is often a resistance to specific scientific conclusions or findings. Why might this be?

References

Kuhn, T. S. (2012). The structure of scientific revolutions: 50th anniversary edition. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (2011). Objectivity, value judgment, and theory choice, in T. S. Kuhn (Ed.), The essential tension: Selected studies in scientific tradition and change (pp. 320-339). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com

attributions

“Thinking like a Psychological Scientist” by Erin I. Smith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

In research, information systematically collected for analysis and interpretation.

A tentative explanation that is subject to testing.

To draw general conclusions from specific observations.

In research, a number of people selected from a population to serve as an example of that population.

Beliefs or practices that are presented as being scientific, or which are mistaken for being scientific, but which are not scientific (e.g., astrology, the use of celestial bodies to make predictions about human behaviors, and which presents itself as founded in astronomy, the actual scientific study of celestial objects. Astrology is a pseudoscience unable to be falsified, whereas astronomy is a legitimate scientific discipline).

In science, the ability of a claim to be tested and—possibly—refuted; a defining feature of science.

A measure of the degree of certainty of the occurrence of an event.

A form of reasoning in which a general conclusion is inferred from a set of observations (e.g., noting that “the driver in that car was texting; he just cut me off then ran a red light!” (a specific observation), which leads to the general conclusion that texting while driving is dangerous).

A form of reasoning in which a given premise determines the interpretation of specific observations (e.g., All birds have feathers; since a duck is a bird, it has feathers).

In research, the degree to which a sample is a typical example of the population from which it is drawn.

A piece of biased evidence, usually drawn from personal experience, used to support a conclusion that may or may not be correct.

In research, all the people belonging to a particular group (e.g., the population of left handed people).

In statistics, the measure of relatedness of two or more variables.

In statistics, a test created to determine the chances that an alternative hypothesis would produce a result as extreme as the one observed if the null hypothesis were actually true.

In statistics, the relative frequency that a particular value occurs for each possible value of a given variable.

In statistics, the error of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true.

In statistics, the error of failing to reject the null hypothesis when it is false.

In statistics, the established threshold for determining whether a given value occurs by chance.

An explanation for observed phenomena that is empirically well-supported, consistent, and fruitful (predictive).

Concerned with observation and/or the ability to verify a claim.

Being free of personal bias.

Objective information about the world.

Belief about the way things should be.

In science, there are complementary understandings and explanations of phenomena.

In research, the determination that one variable causes—is responsible for—an effect.

In research, the degree to which one can extend conclusions drawn from the findings of a study to other groups or situations not included in the study.