Psych in Real Life: Latent Learning

Learning Objectives

- Describe Edward Tolman’s experiment on latent learning

Edward Tolman was studying traditional trial-and-error learning when he realized that some of his research subjects (rats) actually knew more than their behavior initially indicated. In one of Tolman’s classic experiments, he observed the behavior of three groups of hungry rats that were learning to navigate mazes.

The first group always received a food reward at the end of the maze, so the payoff for learning the maze was real and immediate. The second group never received any food reward, so there was no incentive to learn to navigate the maze effectively. The third group was like the second group for the first 10 days, but on the 11th day, food was now placed at the end of the maze.

As you might expect when considering the principles of conditioning, the rats in the first group quickly learned to negotiate the maze, while the rats of the second group seemed to wander aimlessly through it. The rats in the third group, however, although they wandered aimlessly for the first 10 days, quickly learned to navigate to the end of the maze as soon as they received food on day 11. By the next day, the rats in the third group had caught up in their learning to the rats that had been rewarded from the beginning. It was clear to Tolman that the rats that had been allowed to experience the maze, even without any reinforcement, had nevertheless learned something, and Tolman called this latent learning. Latent learning is to learning that is not reinforced and not demonstrated until there is motivation to do so. Tolman argued that the rats had formed a “cognitive map” of the maze but did not demonstrate this knowledge until they received reinforcement.

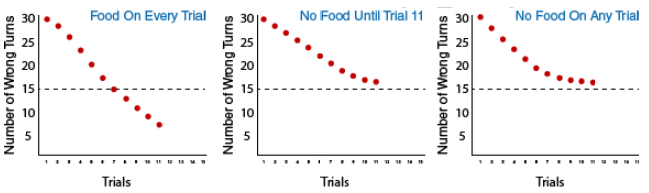

Now that you’ve learned the design of the study, let’s take a closer look at what happened in the study. The results for the three groups will be shown in these graphs. The graph on the left is for the group that always received food. The middle graph is for the rats that did not received food for the first 10 trials and then, on Trial #11, started to receive food. The graph on the right is for rats that never received food. The red dots indicate how the rats did in each of the three conditions. The Y-axis (vertical axis) indicates how many wrong turns, or errors, the rats in each condition made on average. The X-axis (horizontal axis) shows the different trials. This is the first trial, so none of the rats knew there was food in the food box.

Let’s see how the rats in each group did over the next four trials. Notice all the groups made fewer errors and continue to do so in Trial 4. Now look more closely at trials 4 and 5. Are you starting to see a difference between the groups? Use the dotted line in the middle of the graphs as a reference point for comparing the groups. Which group seems to be getting to the line faster?

Let’s pick up at Trial 7. Notice that the group on the left, which receives food on every trial, continues to improve at a faster rate than the other two groups. These two groups are both performing at the same level and are making about 20 wrong turns on each trial on average. At Trial 10, we are at a critical point in the experiment because things are about to change on the next trial for the rats shown in the middle graph. Something special will happen to this group. Food will now appear in the food box! Of course, they won’t know this until they get there, so the effects of the change should not appear on the next trial. As you can see from the graphs for Trial 11, the groups shown in the middle and right graphs still look the same. The rats in the left group are now making fewer wrong turns than either of the other two groups.

Work It out

Your task here is to predict what is going to happen on Trial 12 for the “no food until Trial 11” group.

Option A: Notice that this result is the same as the “no food on any trial” group. So, if you choose option A, you think that they will not act differently now than they acted on the first 11 trials and they will continue to make a lot of wrong turns.

Option B: This option suggests that they are now motivated to learn the path to the food, but that they will do so in small steps, just as we have seen for all three groups up to this point. Option B says that they are moving in the direction of the “food on every trial” group, but that it will take some extra learning to get there.

Option C: This option says that they already know the path to the food and, now that they are motivated to get there, they will show that they already know just as much as the “food on every trial” group. Their performance on Trial 12 will be the same as the low-error performance of the “food on every trial” group.

So, what happened to the rats in the group that began to receive food at Trial 11? They were immediately able to make their way through the maze without making many wrong turns to get to the food. They made about the same number of errors as the “Food on Every Trial” group! Tolman interpreted this to mean that they had created a mental map of the maze during the first 11 trials…and when they needed to get food, they could find their way to the food box very efficiently!

As we look at trials 13, 14, and 15, notice how the graph for the group of rats on the left –- the ones that received food on every trial — and the graph for the group of rats in the middle — the ones that started receiving food at trial 11 — now look similar. And the rats that never received food continued to make more than 15 errors in each trial on average.

attributions

Authored by: Patrick Carroll for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

Latent Learning: Learning Before Doing. Provided by: Open Learning Initiative. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike