Diagnosing and Classifying Psychological Disorders

Learning Objectives

- Describe the basic features of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) and how it is used to classify disorders

A first step in the study of psychological disorders is carefully and systematically discerning significant signs and symptoms. How do mental health professionals ascertain whether or not a person’s inner states and behaviors truly represent a psychological disorder? Arriving at a proper diagnosis—that is, appropriately identifying and labeling a set of defined symptoms—is absolutely crucial. This process enables professionals to use a common language with others in the field and aids in communication about the disorder with the patient, colleagues and the public. A proper diagnosis is an essential element to guide proper and successful treatment. For these reasons, classification systems that organize psychological disorders systematically are necessary.

Diagnostic And Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)

Although a number of classification systems have been developed over time, the one that is used by most mental health professionals in the United States is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association (2013). (Note that the American Psychiatric Association differs from the American Psychological Association; both are abbreviated APA.) Additions and revisions were made in March 2022, so the most current edition is called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). This textbook includes the updates from the DSM-5-TR, though we continue to reference the diagnostic manual simply as the DSM-5.

The first edition of the DSM, published in 1952, classified psychological disorders according to a format developed by the U.S. Army during World War II (Clegg, 2012). In the years since, the DSM has undergone numerous revisions and editions. The most recent edition, published in 2013, is the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). The DSM-5 includes many categories of disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and dissociative disorders). Each disorder is described in detail, including:

- an overview of the disorder (diagnostic features),

- specific symptoms required for diagnosis (diagnostic criteria),

- what percent of the population is thought to be afflicted with the disorder (prevalence information), and

- risk factors associated with the disorder.

Figure 1 shows lifetime prevalence rates—the percentage of people in a population who develop a disorder in their lifetime—of various psychological disorders among U.S. adults. These data were based on a national sample of 9,282 U.S. residents (National Comorbidity Survey, 2007).

| DSM Disorder | Total | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Depressive Disorder | 17% | 20% | 13% |

| Alcohol Abuse | 13% | 7% | 20% |

| Specific Phobia | 13% | 16% | 8% |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 12% | 13% | 11% |

| Drug Abuse | 8% | 5% | 12% |

| Post-traumatic Stress Disorder | 7% | 10% | 3% |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 6% | 7% | 4% |

| Panic Disorder | 5% | 6% | 3% |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 3% | 3% | 2% |

| Persistent Depressive Disorder | 3% | 3% | 2% |

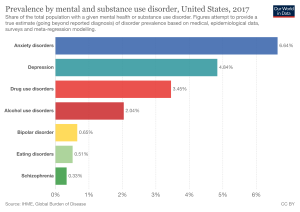

More recent data shows that the most prevalent disorders at any given time (not over a lifetime) are anxiety disorders, as shown in the following chart.[1]

The DSM-5 also provides information about comorbidity; the co-occurrence of two disorders. For example, the DSM-5 mentions that 41% of people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) also meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (Figure 2). Drug use is highly comorbid with other mental illnesses; 6 out of 10 people who have a substance use disorder also suffer from another form of mental illness (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2007).

Comorbidity

Co-occurrence and comorbidity of psychological disorders are quite common, and some of the most pervasive comorbidities involve substance use disorders that co-occur with psychological disorders. Indeed, some estimates suggest that around a quarter of people who suffer from the most severe cases of mental illness exhibit substance use disorder as well. Conversely, around 10 percent of individuals seeking treatment for substance use disorder have serious mental illnesses. Observations such as these have important implications for treatment options that are available. When people with a mental illness are also habitual drug users, their symptoms can be exacerbated and resistant to treatment. Furthermore, it is not always clear whether the symptoms are due to drug use, the mental illness, or a combination of the two. Therefore, it is recommended that behavior is observed in situations in which the individual has ceased using drugs and is no longer experiencing withdrawal from the drug in order to make the most accurate diagnosis (NIDA, 2018).

Obviously, substance use disorders are not the only possible comorbidities. In fact, some of the most common psychological disorders tend to co-occur. For instance, more than half of individuals who have a primary diagnosis of depressive disorder are estimated to exhibit some sort of anxiety disorder. The reverse is also true for those diagnosed with a primary diagnosis of an anxiety disorder. Further, anxiety disorders and major depression have a high rate of comorbidity with several other psychological disorders (Al-Asadi, Klein, & Meyer, 2015).

The DSM has changed considerably in the half-century since it was originally published. The first two editions of the DSM, for example, listed homosexuality as a disorder; however, in 1973, the APA voted to remove it from the manual (Silverstein, 2009). While the DSM-III did not list homosexuality as a disorder, it introduced a new diagnosis, ego-dystonic homosexuality, which emphasized homosexual arousal that the patient viewed as interfering with desired heterosexual relationships and causing distress for the individual. This new diagnosis was considered by many as a compromise to appease those who viewed homosexuality as a mental illness. Other professionals questioned how appropriate it was to have a separate diagnosis that described the content of an individual’s distress. In 1986, the diagnosis was removed from the DSM-III-R (Herek, 2012).

Additionally, beginning with the DSM-III in 1980, mental disorders have been described in much greater detail, and the number of diagnosable conditions has grown steadily, as has the size of the manual itself. DSM-I included 106 diagnoses and was 130 total pages, whereas DSM-III included more than 2 times as many diagnoses (265) and was nearly seven times its size (886 total pages) (Mayes & Horowitz, 2005). Although DSM-5 is longer than DSM-IV, the volume includes only 237 disorders, a decrease from the 297 disorders that were listed in DSM-IV. The latest edition, DSM-5, includes revisions in the organization and naming of categories and in the diagnostic criteria for various disorders (Regier, Kuhl, & Kupfer, 2012), while emphasizing careful consideration of the importance of gender and cultural difference in the expression of various symptoms (Fisher, 2010).

Some believe that establishing new diagnoses might overpathologize the human condition by turning common human problems into mental illnesses (The Associated Press, 2013). Indeed, the finding that nearly half of all Americans will meet the criteria for a DSM disorder at some point in their life (Kessler et al., 2005) likely fuels much of this skepticism. The DSM-5 is also criticized on the grounds that its diagnostic criteria have been loosened, thereby threatening to “turn our current diagnostic inflation into diagnostic hyperinflation” (Frances, 2012, para. 22). For example, DSM-IV specified that the symptoms of major depressive disorder must not be attributable to normal bereavement (loss of a loved one). The DSM-5, however, removed this bereavement exclusion, essentially meaning that grief and sadness after a loved one’s death can constitute major depressive disorder.

International Classification of Diseases

A second classification system, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), is also widely recognized. Published by the World Health Organization (WHO), the ICD was developed in Europe shortly after World War II and, like the DSM, has been revised several times. The categories of psychological disorders in both the DSM and ICD are similar, as are the criteria for specific disorders; however, some differences exist. Although the ICD is used for clinical purposes, this tool is also used to examine the general health of populations and to monitor the prevalence of diseases and other health problems internationally (WHO, 2013). The ICD is in its 10th edition (ICD-10); however, efforts are now underway to develop a new edition (ICD-11) that, in conjunction with the changes in DSM-5, will help harmonize the two classification systems as much as possible (APA, 2013).

A study that compared the use of the two classification systems found that worldwide the ICD is more frequently used for clinical diagnosis, whereas the DSM is more valued for research (Mezzich, 2002). Most research findings concerning the etiology and treatment of psychological disorders are based on criteria set forth in the DSM (Oltmanns & Castonguay, 2013). The DSM also includes more explicit disorder criteria, along with an extensive and helpful explanatory text (Regier et al., 2012). The DSM is the classification system of choice among U.S. mental health professionals, and this module is based on the DSM paradigm.

Compassionate View of Psychological Disorders

As these disorders are outlined, please bear two things in mind. First, remember that psychological disorders represent extremes of inner experience and behavior. If, while reading about these disorders, you feel that these descriptions begin to personally characterize you, do not worry—this moment of enlightenment probably means nothing more than you are normal. Each of us experiences episodes of sadness, anxiety, and preoccupation with certain thoughts—times when we do not quite feel ourselves. These episodes should not be considered problematic unless the accompanying thoughts and behaviors become extreme and have a disruptive effect on one’s life.

Second, understand that people with psychological disorders are far more than just embodiments of their disorders. We do not use terms such as schizophrenics, depressives, or phobics because they are labels that objectify people who suffer from these conditions, thus promoting biased and disparaging assumptions about them. It is important to remember that a psychological disorder is not what a person is; it is something that a person has—through no fault of their own. As is the case with cancer or diabetes, those with psychological disorders suffer debilitating, often painful conditions that are not of their own choosing. These individuals deserve to be viewed and treated with compassion, understanding, and dignity.

Watch It

Watch this CrashCourse Psychology video to better understand the history of diagnosing psychological disorders and how they are classified.

attributions

Diagnosing and Classifying Psychological Disorders. Authored by: OpenStax College. License: CC BY: Attribution.

Psychological Disorders: Crash Course Psychology #28. Provided by: CrashCourse. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2018) - "Mental Health". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health' [Online Resource] ↵

determination of which disorder a set of symptoms represents

authoritative index of mental disorders and the criteria for their diagnosis; published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA)

co-occurrence of two disorders in the same individual

authoritative index of mental and physical diseases, including infectious diseases, and the criteria for their diagnosis; published by the World Health Organization (WHO)